7.2 Court Jurisdictions

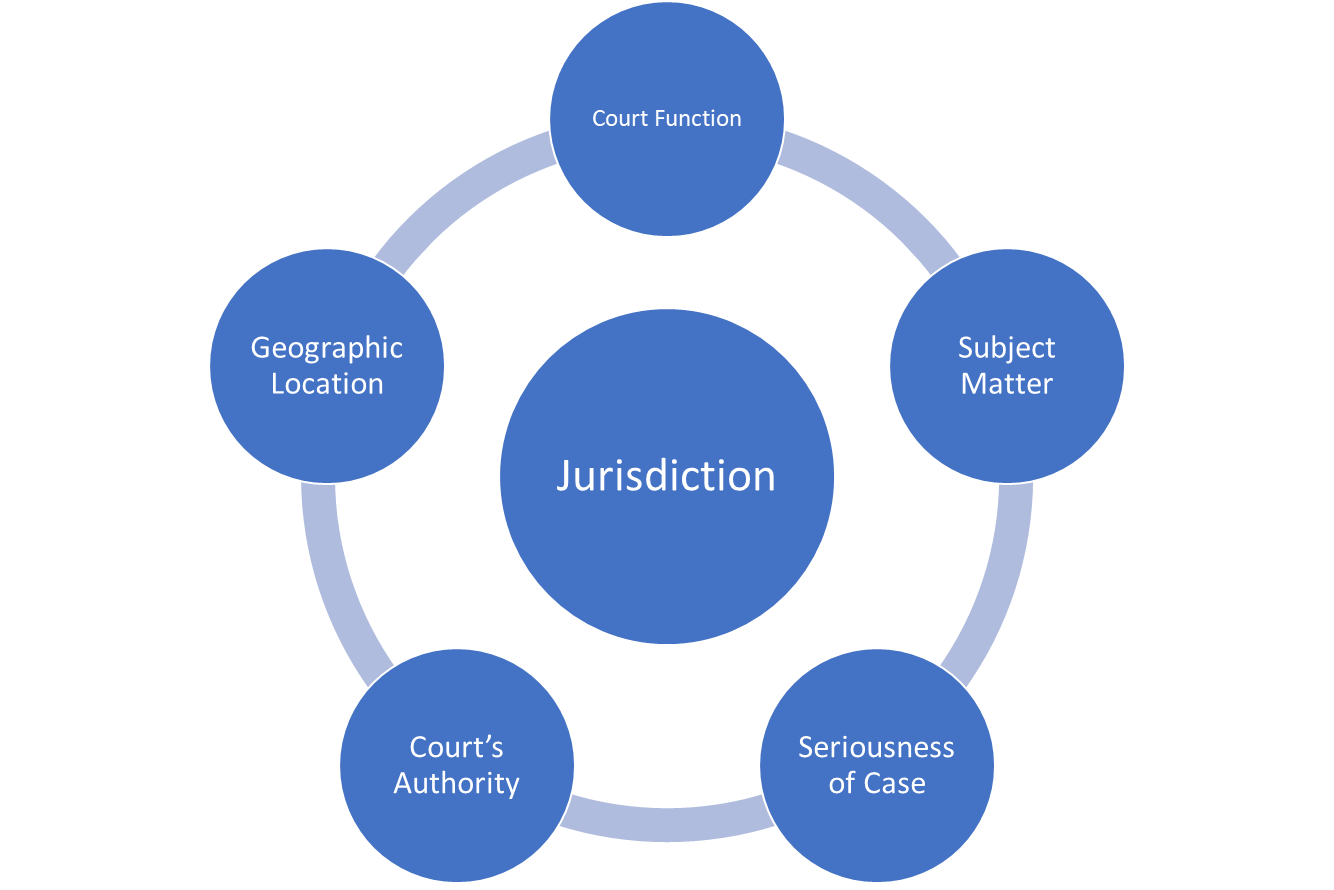

In the courts, jurisdiction refers to the legal power to hear and decide a case. It’s a fundamental aspect of any court proceeding. Imagine you’re a student who believes a teacher from another school changed your grade unfairly. Just as that teacher wouldn’t have the authority to alter your grade, a court lacking proper jurisdiction wouldn’t have the power to hear your case. In both situations, the outcome would change because the necessary authority isn’t present. Understanding jurisdiction helps clarify where legal actions can be pursued effectively. In this section, we’ll explore various types of jurisdiction pictured in figure 7.2, based on factors like the court’s function, the type of case, its seriousness, the court’s power, and its location.

Jurisdiction Based on the Function of the Court

The court’s power can be based on its function. For example, a trial court differs from an appellate or appeals court in its specific function in the case. The trial court has the initial authority to try the case and decide the outcome. In contrast, the appellate court has the authority to overrule that outcome if a serious mistake is made by the trial court. The federal and state court systems have hierarchies that divide trial and appellate courts.

Trial courts have jurisdiction over pretrial matters, trials, sentencing, probation, and parole violations. Trial courts deal with facts. Did the defendant stab the victim? Was the eyewitness able to clearly see the stabbing? Did the probationer willfully violate the terms of probation? As a result, trial courts determine guilt and impose punishments.

Appellate courts, also known as appeals courts, review decisions made by trial courts. They focus on legal matters such as whether the trial judge provided proper instructions to the jury, if evidence was correctly suppressed, or if a defendant can raise certain defenses. These courts correct legal mistakes made by trial courts and address new legal questions. Instead of holding hearings, they review the trial court’s record or transcript. Sometimes, they determine if there’s enough evidence to support a conviction.

Jurisdiction Based on Subject Matter

The authority of the court can also be based on the subject matter of the case. For example, criminal courts handle criminal matters, tax courts handle tax matters, and customs and patent courts handle patent matters. Because the higher appellate courts are usually designed to hear different types of cases, the issue of subject matter jurisdiction is mostly relevant in lower trial courts. However, each state is different, and state constitutions dictate the specific structure of the state court system. The specialized courts represent only a small portion of all trial courts. Most trial courts are not limited to a particular subject but may deal with all fields. More than 60 million cases in 2020, and more than 95 percent of these cases are from state courts (Kerper, 1979, p. 34). State courts also differ in how they select judges and the type of cases each court can hear.

Jurisdiction Based on the Seriousness of the Case

The seriousness of the case may also affect the court’s jurisdiction. Most of the trial courts are called courts of general jurisdictions, meaning that they can hear almost any type of case. However, the courts of limited jurisdiction can only try minor misdemeanor cases such as petty crimes, violations, and infractions.

Jurisdiction Based on the Court’s Authority

Jurisdiction also refers to the court’s authority over the parties in the case. For example, juvenile courts have jurisdiction over delinquency cases involving youth. Other court jurisdictions are based on the special nature of the parties, such as military tribunals and the U.S. Court for the Armed Services.

Jurisdiction Based on Location

Finally, jurisdiction is also tied to our system of federalism, the autonomy of national and state governments. State courts have jurisdiction over state matters, and federal courts have jurisdiction over federal matters. Jurisdiction is most commonly known to represent geographic locations of the court’s oversight. For example, Oregon courts do not have jurisdiction over crimes in California. In the next section of this chapter, we will discuss how courts exercise their jurisdiction at the state and federal levels of government.

Licenses and Attributions for Court Jurisdictions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Court Jurisdictions” is adapted from “7.2. Jurisdiction” by Lore Rutz-Burri in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Sam Arungwa, revisions by Roxie Supplee, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include editing for clarity and removing video links.

Figure 7.2. Elements of Court Jurisdiction, a figure showing the different elements that make up court jurisdiction, by Roxie Supplee, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

The authority of a court to hear and decide a case.

Courts that review decisions made by trial courts.

A sentence that allows a convicted person to remain in the community under the supervision of a probation officer, instead of going to jail or prison.

The release of a prisoner under supervision after serving a portion of their sentence.

One who has suffered direct or threatened physical, financial, or emotional harm as a result of the commission of a crime.

Courts that can only hear specific types of cases, typically minor offenses or civil matters.

These are the least dangerous types of crimes which can include, depending on the location, public intoxication, prostitution, and graffiti, among others.