8.6 Incapacitation

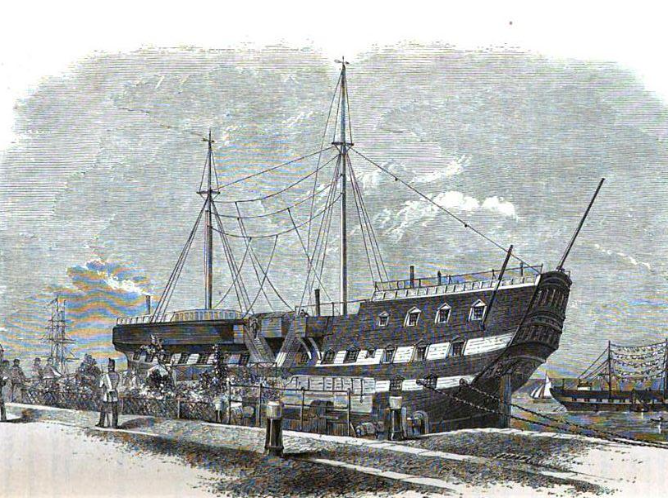

Rooted in the concept of banishing individuals from society, incapacitation is the removal of an individual from society for a set amount of time so they cannot commit crimes. In British history, this often occurred on hulks, as seen in figure 8.2. Hulks were large ships that carried convicted criminals to other places so they would be unable to commit crimes in their community any longer.

In the 1970s, punishment became much more of a political topic in the United States, and perceptions of the fear of crime became important. Lawmakers, politicians, and others began to campaign on their toughness on crime, using the fear of crime and criminals to benefit their agendas to impose punitive prison sentences. This is considered collective incapacitation, or the incarceration of large groups of individuals to remove their ability to commit crimes for a set amount of time in the future.

Since this time, and exacerbated in the 1980s and 1990s, there has been an increasing use of punishment by prison sentences. For instance, we saw a 500% increase in the prison population between 1980 and 2020 (Ghandnoosh, 2022). The politicization of punishment increased the overall incarcerated population in two ways. First, by allowing decision makers more discretion, as a society, we have gotten tougher on crime. In turn, more people are now being sentenced to prison, and they may have gone to specialized probation or community-sanction alternatives otherwise. Second, these same attitudes have led to harsher and lengthier punishments for certain crimes. Individuals are being sent away for longer sentences, which has caused the intake-to-release ratio to change and created enormous buildups of the prison population. We will cover more on this topic in Chapter 9, specifically how these buildups have disproportionately affected minority populations.

The incapacitative ideology followed this design for several decades, but in the early 1990s, three-strike policies were implemented that would target individuals more specifically based on prior offenses or crimes committed. These selective incapacitation policies would incarcerate an individual for greater lengths of time if they had prior offenses. These policies incarcerated certain individuals for longer periods than others, even when they had committed the same crime. Thus, it removed their individual ability to commit crimes in society for greater periods of time as they were incarcerated.

There are mixed feelings about selective and collective incapacitation. Policymakers promote incapacitation by giving examples of locking certain individuals away in order to help calm the fear of crime. Others, like Blokland and Nieuwbeerta (2007), have stated that there is little evidence to suggest that this solves the problem. Selective incapacitation has evolved to include tighter crime control strategies that target individuals who repeat the same offenses. Others opt for tougher community supervision options to keep individuals under supervision longer. In summary, we have seen a shift from collective incapacitation to a more selective approach.

After learning about retribution, deterrence, and incapacitation, we are left with questions: do they work? And at what cost? Are there other methods that seem the same or are more effective than the ones already in practice? This takes us to the last of the four main punishment ideologies: rehabilitation.

Licenses and Attributions for Incapacitation

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Philosophies of Punishment” is adapted from “8.1. A Brief History of the Philosophies of Punishment”, “8.2. Retribution”, “8.3. Deterrence”, “8.4. Incapacitation”, and “8.5. Rehabilitation” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Megan Gonzalez, revisions by Roxie Supplee, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 include editing for clarity.

Figure 8.2. “The Warrior Prison Ship” by Hideokun, Wikipedia is in the Public Domain.

Removing an individual from society for a set period to prevent them from committing crimes.

A penalty imposed on someone who has committed a crime.

A facility that houses people convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to long terms of incarceration.

A sentence that allows a convicted person to remain in the community under the supervision of a probation officer, instead of going to jail or prison.

Punishment focused on revenge or payback for a crime.

The goal of discouraging criminal behavior through punishment or the threat of punishment.

The process of helping someone who has committed a crime change their behavior and become a productive member of society.