9.4 Specialty Courts

Specialty Courts are courts designed to handle individuals charged or convicted with specific crimes or who have specific needs related to their crimes. The idea is that these courts are better equipped to address the specific issues the individual faces. They are unique because the courtroom works in a non-adversarial way to identify supportive programs to successfully rehabilitate the individual. Judges, prosecutors, case workers, program coordinators, and others all work together within the specialty court to develop individual treatment and programming plans. In many cases, successful completion of these plans allows for the individual’s charges to be dismissed or expunged. For a listing of some of the nationally-recognized specialty courts, visit the National Drug Court Resource Center [Website].

Drug courts are one of the specialty types of courts that were first developed in the mid-1980s in Dade County, Florida. As with other intermediate sanctions, drug courts flourished in the United States rapidly, to the point that they are now in every state. Currently, more than 3,800 drug, treatment, or specialty courts operate in the United States, as reported by the Office of Justice Programs (2022). With the growing popularity of drug courts, jurisdictions began incorporating other specialty courts, including Veterans Courts, Mental Health Courts, Domestic Violence Courts, Family Courts, Reentry Courts, and others. To learn more about Drug Courts, watch the YouTube video “What are Drug Courts?” in figure 9.6.

Specialty Court Effectiveness

While the results on Specialty Courts are mixed, as a whole, drug courts are more favorable than the control of boot camps and ISPs. The results are mixed, largely due to how successes and failures are assessed and tracked. If only talking about the cost savings versus jail or prison, they are seen as an effective community alternative. If looking at recidivism, it depends on whether the metric is looking at relapses, solely drug charges, any arrests, or persistence models (length of time before arrest). As a whole, the risk of being rearrested for a drug crime for individuals from drug courts has shown lower rates than their comparison group. While other research, shared by the Vera Institute, has demonstrated that graduates of drug court programs were half as likely to recidivate (10 percent vs. 20 percent) (Fluellen & Trone, 2000). To learn more about the effectiveness of Drug Courts, watch the video “Part 3: Drug Courts are Effective” in figure 9.7. While more research is still required, specialty courts are currently seen as an effective community alternative.

House Arrest/Electronic Monitoring

House arrest is when an individual is remanded to stay home for confinement as a punishment in lieu of jail or prison. There are built-in provisions allowing individuals to attend places of worship, places of employment, and food places. Otherwise, individuals are expected to be home. It is difficult to assess how many are on house arrest at any given time, as these are often short stents given during the early stages of probation or pretrial release.

A component that is often paired with the house arrest model is electronic monitoring (EM). This electronic bracelet or device is equipped with Global Positioning Systems (GPS). The individual wears the device, and an agency official tracks their actions and locations to ensure they only travel and move within the confines of their conditions. To learn more about the growth in EM use, review the article Use of Electronic Offender-Tracking Devices Expands Sharply [Website].

House Arrest/Electronic Monitoring Effectiveness

As mentioned above, house arrest is often joined with EM. Many of the studies incorporate both sanctions at the same time. Given the difficulty in separating EM from house arrest in studies, less is known about the independent effects of house arrest. However, it is certainly a cost-saving mechanism over other forms of sanctions. There is a relatively no-cost to low-cost for house arrest, not coupled with electronic monitoring, especially when comparing house arrest to intensive supervised probation. In all, house arrest would probably best serve individuals with low criminogenic risks and needs. However, it is also argued that those individuals already need little sanctions in order to be successful. Thus, the utility of house arrest is debatable.

The cost of pairing house arrest with EM can be similar to that of a cell phone contract payment each month, and these costs often fall on the individual and not the agency to cover. This can cause financial hardship on the individual, and outside of tracking the person’s location to ensure they are where they are supposed to be, the agencies have to impose additional rules. Due to the rise of the use of EM during the COVID-19 pandemic, there have been quite a few critics of EM, as noted in George Washington University Law School’s research titled, The Electronic Prisons: The Operation of Ankle Monitoring in the Criminal Legal System [Website]. Check out the report if you would like to learn more.

Community Residential Facilities

Community Residential Facilities (CRFs) have long been used to control and house individuals. Dating back to the early 1800s from England and Ireland, halfway houses began around 1820 in Massachusetts. Initially, they were designed to help a person “get back on their feet” and were generally funded benevolently by non-profit organizations like the Salvation Army.

Currently, halfway houses are typically used as a stopping point for individuals coming out of prisons to assist with reentry into the community. Still, they have also recently been used as more secure measures of monitoring individuals in place of going to prison. They are even used as a test measure of parole. With the creation of The Electronic Prisons: The Operation of Ankle Monitoring in the Criminal Legal System [Website] in 1964, halfway houses have become an integral part of every state, with mixed but more promising results than ISPs or boot camps. The core design of a halfway house is meant to be a place where individuals can get back on their feet after being released from prison. However, as stated, their uses have evolved, becoming residential or even partial residential places where individuals under correctional control can check in and find reprieve or assistance in order to rejoin society as normal functioning members.

There are some issues regarding the examination of halfway houses. The IHHA breaks down halfway houses into four groups along two dimensions. As discussed, halfway houses were initially funded by private non-profit organizations. However, many halfway houses today (in part due to the IHHA) are both privately and federally (and State) funded. Additionally, halfway houses are also divided into supportive and interventive groups. That is, halfway houses that serve only a minimal function (a place to stay while reintegrating back into society) are generally labeled supportive, whereas interventive halfway houses typically have multiple treatment modalities and may have up to 500 beds. However, most halfway houses fall somewhere in the middle of these two continuums.

Other forms of Community Residential Facilities (CRFs) are often called Community Correctional Centers (CCCs), Transition Centers (TCs), or Community-Based Correctional Facilities (CBCFs), among other names. From this point, these variations will all be considered CRFs, as there are many varieties of facility types and names. However, even two community residential facilities with the same name can be different, as the functions of CRFs can be multifaceted. CRFs can function similarly to halfway houses, or they can provide a stop for individuals just checking in for the day before they go off to their jobs. They can be used for outpatient services, even residential services, where there is a need for public control/safety.

The overall benefit of CRFs is their ability to have an increased focus on rehabilitation at a lower cost than a State institution. This is where their greatest effect can materialize if there is adherence to the principles of effective intervention. As we touched on in the first section on punishment, the principles of effective intervention have been demonstrated to have the best impacts on reductions in recidivism. Collectively, these are called the Principles of Effective Intervention or PEI. These include proper identification of criminogenic risks and needs of individuals, using evidence-based practices that address these items, matching and sorting clients appropriately, and responsivity in terms of programs and services.

The National Institute of Corrections defines evidence-based practices as “the objective, balanced and responsible use of current research and the best available data to guide policy and practice decisions, such that outcomes for consumers are improved” (2022). Based on this definition, Corrections agencies employ evidence-based practices to use the best techniques possible to help individuals who have committed crimes make positive changes. For an optional detailed account of how the PEI integrates into community corrections, see this detailed report by the National Institute of Corrections under the U.S. Department of Justice: Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Community Corrections: The Principles of Effective Intervention [PDF].

Restorative Justice

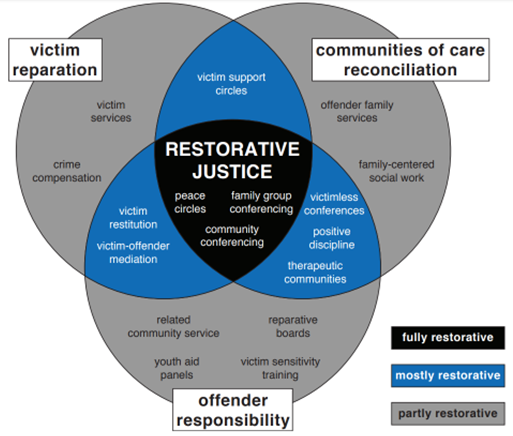

The process of restorative justice (RJ) programs is often linked with community justice organizations and is normally carried out within the community. Therefore, RJ is discussed here in the community corrections section. Restorative justice is a community-based and trauma-informed practice used to build relationships, strengthen communities, encourage accountability, repair harm, and restore relationships when wrongdoings occur. As an intervention following wrongdoing, restorative justice works for the people who have caused harm, the victim(s), and the community members impacted.

Working with a restorative justice facilitator, participants identify harms, needs, and obligations, then make a plan to repair the harm and put things as right as possible. This process, restorative justice conferencing, can also be called victim-offender dialogues. It is within this process that multiple items can occur. First, the victim can be heard within the scope of both the community and the scope of the offense discussed. This provides the victim(s) an opportunity to express the impact on them and understand what was happening from the perspective of the transgressor. At the same time, it allows the person committing the action to potentially take responsibility for the acts committed directly to the victim(s) and the community as a whole. This restorative process provides a level of healing that is often unique. In figure 9.8, you can see the different processes that can occur during the different types of dialogues within restorative justice conferences. To learn more about the restorative process, review the Defining Restorative [PDF] article.

Restorative Justice Effectiveness

For over a quarter century, restorative justice has been demonstrated to show positive outcomes in accountability of harm and satisfaction in the restorative justice process for both offenders and victims. This is true for adults, as well as juveniles, who go through the restorative justice process. Recently, there have been questions about whether a cognitive change occurs in the thought process of individuals completing a restorative justice program. A growing body of research demonstrates cognitive changes that may occur through the successful completion of restorative justice conferencing. This will be an area of increasing interest for practitioners as restorative justice continues to be included in the toolkit of actions within the justice system. OPTIONAL: For additional thoughts on restorative justice from a judge’s perspective, check out this TedTalk: Wesley Saint Clair: The case for restorative justice in juvenile courts [Streaming Video].

Parole and Post Prison Supervision

Parole is an individual’s release (under conditions) after serving a portion of their sentence. It is also accompanied by the threat of re-incarceration if warranted. As with most concepts in our legal system, their roots of parole can be traced back to concepts from England and Europe. If John Augustus is known as the founding father of probation, then Alexander Maconochie [Website] and Zebulon Brockway [Website] could be identified as two of the founding fathers of parole based on their published work related to early parole-like systems (figures 9.9 and 9.10).

Both men were prison reformists during a time in history when many thought incarceration was the solution to crime. They wrote about and implemented, on a small scale, penal systems that rewarded well-behaved incarcerated individuals with the ability to earn “marks” or points toward shortening their sentences and thus allowed early release with stipulations for rejoining the community.

Parole today has greatly evolved based on American values and concepts. Parole in the United States began as a concept at the first American Prison Association meeting in 1870. At the time, there was much support for corrections reform in America. Advocates for reform helped to create the concept of parole and how it would look in the United States, and plans to develop parole grew from there. Parole authorities began to be established within the states, and by the mid-1940s, all states had a parole authority. Parole boards and state parole authorities have fluctuated over the years, but the concept is still practiced to varying degrees today. It is different from probation, which often operates under the judicial branch. Parole typically operates under the executive branch and is aligned with the departments of corrections, as parole is a direct extension of prison terms and release.

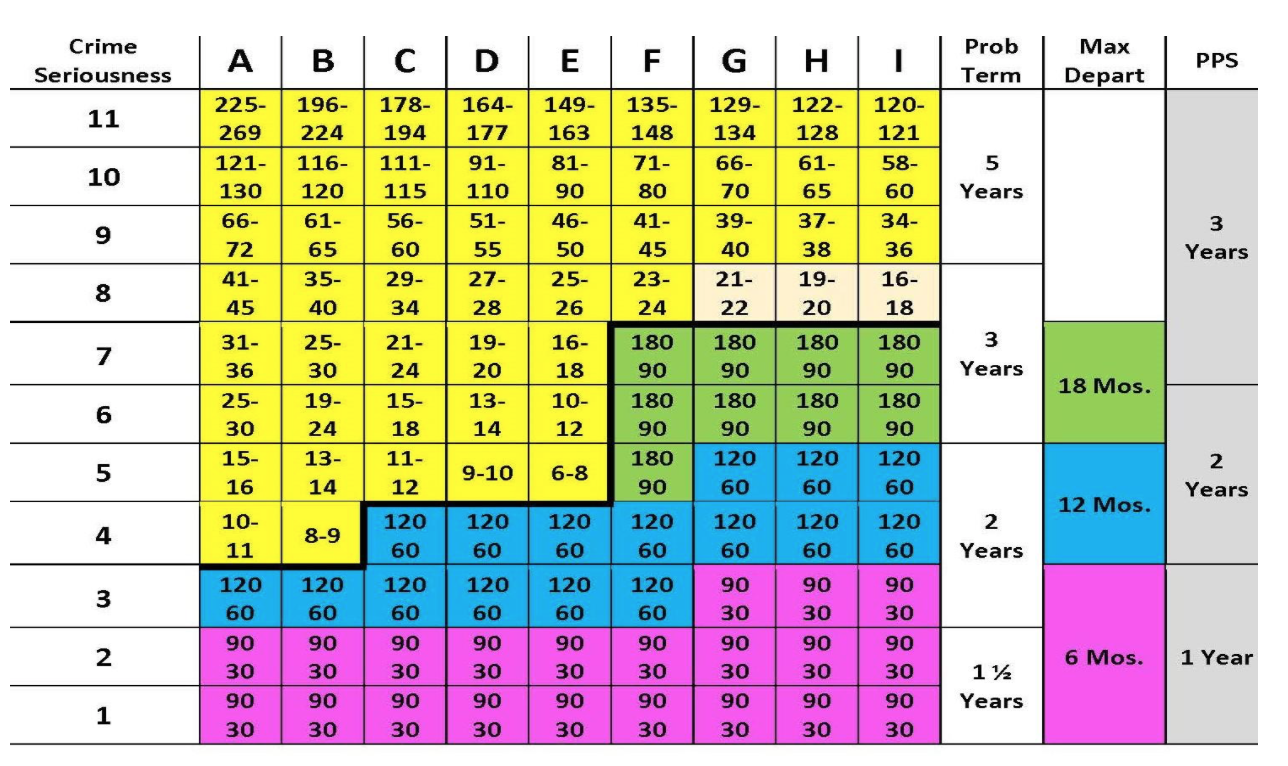

Many states operate a post-prison supervision (PPS) addendum to their sentencing matrix for the punishment of individuals. This addendum is similar to parole in that the individual’s release (under conditions) occurs after serving their prison sentence. As you can see in figure 9.11, the gray PPS section represents the recommended times for parole (post-prison supervision).

Today, there are three basic types of parole in the United States: discretionary, mandatory, and expiatory. Discretionary parole refers to the process where an individual is eligible for parole or goes before a parole board prior to their mandatory parole eligibility date. It is at the discretion of the parole board to grant parole (with conditions) for these individuals. These individuals are generally well-behaved people who have demonstrated they can function within society (have completed all required programming). Discretionary parole had seen a rapid increase in the 1980s but took a marked decrease starting in the early 1990s. In more recent years, it has returned as a viable release mechanism for over 100,000 individuals a year, as noted in a Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report (Hughes et al., 2001).

Mandatory parole occurs when an individual hits a particular point in time in their sentence. When a person is sent to prison, two clocks begin. The first clock is forward counting and continues until the individual’s last day. The second clock starts at the end of their sentence and starts to work backward, proportional to the “good days” an individual has had. Good days are those when a person is free from incidents, write-ups, tickets, or other rule infractions. For instance, for every week that an individual maintains good behavior, they might get two days taken off of the end of their sentence. When these two times converge, this would be the point at which mandatory parole could kick in for them. This must also be conditioned by truth-in-sentencing legislation, or what is considered an 85 percent rule.

Many states have laws in place that stipulate that an individual is not eligible for mandatory parole until they hit 85 percent of their original sentence. Even though the date for the good days would be before 85 percent of a sentence is served, they would only be eligible for mandatory parole once they had achieved 85 percent of their sentence. Recently, states have begun to soften these 85 percent rules as another way to reduce crowding issues. As discretionary parole went down, mandatory parole went up. This is logical, though, as once they had passed a date for discretionary parole, the next date would be their mandatory parole date. These proportions of releases switched in the 1990s (figure 9.12).

Perhaps most troubling is the expiatory release. We see a slow increase of expiatory release in the chart, which continued to climb in the 2000s. Expiatory release (a similar idea to post-prison supervision) means that a person has served their entire sentence length and is being released to the community, not because of their warranted behavior change, but based on the end of their sentence and the need to accommodate incoming individuals. This sometimes means the person has misbehaved enough to nullify their “good days.” This is unfortunate because of the three types of release—it could be argued that these are the individuals who need the most post-prison supervision, and yet, these are the individuals who are typically receiving the smallest amounts of community supervision because the majority of their sentence was completed while incarcerated. With the newer idea of post-prison supervision, individuals are serving their entire sentence behind bars and then have a set amount of time on post-prison supervision in the community following the incarcerated sentence.

Parole Effectiveness

Successful parole completion rates hover around 50 percent, depending on the year being reported. In the Hughes et al. (2001) article, successful completion was roughly 42 percent in 1999. The same issues for failure that are found in probation completion are found in parole completion, including revocation failures, new charges, absconding, and other infractions. This lower-than-expected success rate has prompted many critics to argue against parole. It is suggested that we are being too lenient on some while keeping lower-level individuals in prison for too long. It is also argued that we are releasing dangerous individuals into the community.

Whatever the criticisms are, the questions around parole still remain. What are we to do with the hundreds of thousands of individuals let out of prison each year? A more modern term for parole is called re-entry. The next section covers current issues within corrections, including what we do for individuals who are re-entering society.

Licenses and Attributions for Specialty Courts

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The Role of Community Corrections” is adapted from “9.1 Diversion”, “9.2 Intermediate Sanctions”, “9.3 Probation”, “9.4 Boot Campus/Shock Incarceration”, “9.5 Drug Courts”, “9.6 Halfway Houses”, “9.8 House Arrest”, “9.9 Community Residential Facilities”, “9.10 Restorative Justice”, and “9.11 Parole” by David Carter in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Megan Gonzalez, revisions by Roxie Supplee, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 include minor updates for clarity.

Figure 9.9. Alexander Maconchie is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.10. Zebulon Brockway is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.12. Percentage of Release from State Prison by method of release 1980-2000 by Trudi Radkee, information from the Bureau of Justice Statistics/U.S. Department of Justice/Timothy Hughes/Doris James is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 9.6. “Part 1: What are Drug Courts?” by AmericanUnivJPO is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.7. “Part 3: Drug Courts are Effective” by AmericanUnivJPO is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.8. Defining Restorative by International Institute for Restorative Practices is included under fair use.

Figure 9.11. Oregon Sentencing Guidelines Grid © The State of Oregon Criminal Justice Commission is included under fair use.

Courts designed to handle specific types of cases, such as drug courts or mental health courts.

A person's emotional, psychological, and social well-being. Mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices.

A facility that holds people accused of crimes awaiting trial or those convicted of minor offenses.

A facility that houses people convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to long terms of incarceration.

A penalty imposed on someone who has committed a crime.

A sentence that allows a convicted person to remain in the community under the supervision of a probation officer, instead of going to jail or prison.

A system of rules enforced through social institutions to govern behavior.

The release of a prisoner under supervision after serving a portion of their sentence.

The process of helping someone who has committed a crime change their behavior and become a productive member of society.

Using research and data to guide decisions about criminal justice policies and programs, with the goal of improving outcomes for individuals.

A system that uses community-based programs and placements as alternatives to incarceration for all or part of a sentence.

A community-based approach to justice that focuses on repairing harm, building relationships, and holding offenders accountable.

When an organization takes responsibility for its actions and the consequences of those actions.

One who has suffered direct or threatened physical, financial, or emotional harm as a result of the commission of a crime.

A period of supervision following release from prison, with conditions similar to parole.