10.2 Theories

Throughout the developmental period referred to as middle childhood, cognitive processes continue expanding. As with any theory, a cognitive theory provides an empirically tested perspective to the understanding of how children’s cognitive development occurs.

Refer to Chapter 2 to read more about what theory is and major theories in human development.

10.2.1 Vygotsky

Chapter 2 introduced Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) and his sociocultural theory. In middle childhood, sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and social interaction in cognitive development. During this developmental period, many children begin leaving home to attend school. Social experiences expand to include classmates, teachers, and other adults such as a friend’s caregivers or adults leading extra-curricular events.

Take a minute to think about how cultural and social experiences may have shaped your cognitive development in middle childhood. Maybe a classmate practiced a particular religion you were introduced to, or you can recall social interactions at school or extra-curricular clubs such as scouts, 4-H, or a church youth group that influenced your thinking or language (Figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Image of children smiling.

Vygotsky also believed that a teacher or peer could help guide the learning process with just the right amount of support, also known as scaffolding. Scaffolding promotes the development of cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development (see Chapter 2 for more on the zone of proximal development and scaffolding).

The expanding social experiences in middle childhood provide children with opportunities to acquire new skills and capabilities. Adults such as caregivers and teachers can assist through a process that Barbara Rogoff (1990) refers to as guided participation. Guided participation is when a learner actively acquires new culturally valuable skills and capabilities through a meaningful, collaborative activity with an assisting, more experienced adult (Figure 10.5). Guided play is another useful pedagogical approach using the same concept (Hirsh-Pasek, Golinkoff, Nesbitt, Lautenbach, Blinkoff, Fifer, 2022). In guided play, the caregiver or teacher curates a playful experience that is child-centered and scaffolds the experience for learning (Weisberg et al., 2016). These processes reveal the Vygotskian view of cognitive development “as the transformation of socially-shared activities into internalized processes,” or an act of enculturation (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996). In this way, children expand cognitive development by participating in it with others.

Figure 10.2. Image of teacher dancing with students.

10.2.2 Piaget

Whereas Vygotsky viewed social interactions as playing an active role in development, Piaget viewed children as having an active role in their development. For more information on Piaget’s theory on cognitive development, see chapter 2, and for more information on stages of cognitive development before middle childhood, see chapters 5, 7, and 9.

10.2.2.1 Concrete Operational Stage

According to Piaget children are in the concrete operational stage of cognitive development during middle childhood, which is approximately ages 7–11. Cognition at this stage of development incorporates logic, and throughout middle childhood school-aged children will develop toward mastery of using logic in very concrete ways. Children presumed to be at this stage of development can investigate the physical world around them and apply logic to principles of cause and effect. Additionally, they can build on their experiences by applying inductive reasoning and problem-solving to the physical world around them. Inductive reasoning represents the concrete reasoning abilities at this stage, for example if a child rides a bus to school and only sees their friends riding the bus to school, then using inductive reasoning the child might assume that all students ride a bus to school. Building on current schemata, especially concrete schema (i.e., those that have been developed based on what children have seen, touched, or directly experienced), concrete operational thinkers can also classify and organize objects by size, distance, and various other physical properties. Below are skills that children are working to master during the concrete operational stage.

|

Classification |

As children’s experiences and vocabularies grow, they build schemata and can organize, or classify, objects in many different ways. Classification can include new ways of arranging information, categorizing information, or creating classes of information. They understand hierarchies and can arrange objects into a variety of classes and subclasses. |

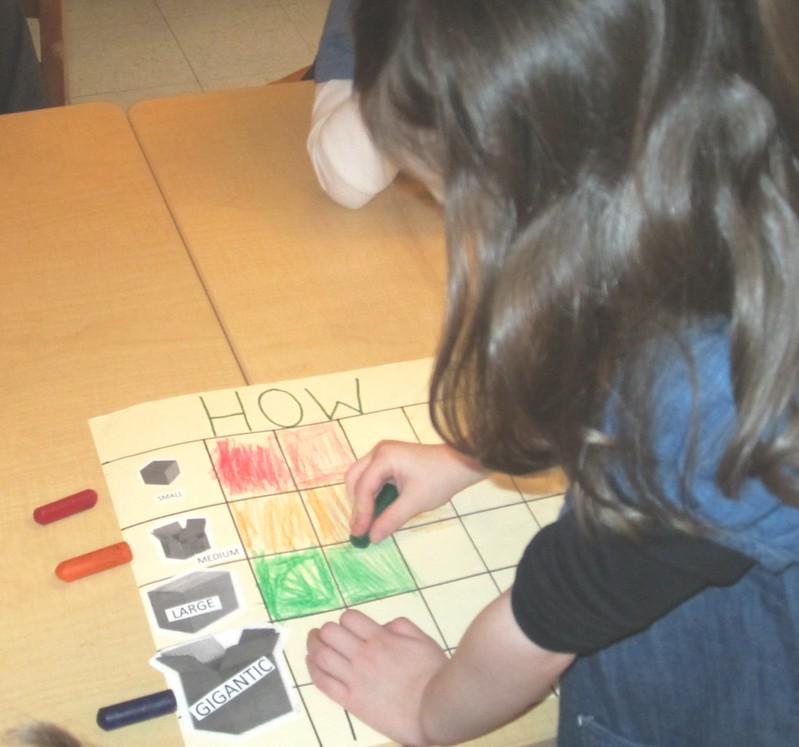

Figure 10.3. Child counting and categorizing information is an example of classification. |

|

Identity |

One feature of concrete operational thought is the understanding that objects have an identity or qualities that do not change even if the object is altered in some way. For instance, the mass of an object does not change by rearranging it. A piece of chalk is still chalk even when the piece is broken in two. |

|

|

Reversibility |

Children are also mastering the ability to think through steps logically, including the ability to work backward to the beginning of a process or the understanding that objects can be altered and then return to a previous state. For example, water can be frozen and then thawed to become liquid again (Figure 10.6), but eggs cannot be unscrambled. Arithmetic operations are reversible as well: 2 + 3 = 5 and 5 – 3 = 2. |

|

|

Seriation |

Children in this stage are also able to arrange items quantitatively, such as length or weight, in a methodical way. For example, a child can systematically arrange a set of different-sized sticks in order by length, while younger children would not approach the task systematically. |

|

|

Conservation |

Concrete operational thinkers are also able to understand the concept of conservation, meaning that changing one quality can be compensated for by changes in another quality. For example, water in a tall narrow container is equal to water in a shorter, but wider container. |

|

|

Transitivity |

Being able to understand how objects are related to one another is referred to as transitivity. This means that if one understands that a dog is a mammal and that a boxer is a dog, then a boxer must be a mammal. |

There are many criticisms of Piaget and the methodological approaches used. Despite the contributions to the field of child development, a major limitation of Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is the lack of or acknowledgment of cultural influences on cognitive development.

10.2.2.2 Culturally Responsive Approaches to Piaget

Readiness is an important element of Piaget’s work, meaning that children should be taught certain concepts when they are ready and at the appropriate stage of cognitive development. Beyond the criticisms, as mentioned at the beginning of the chapter for these theorists, there have been empirical studies contradicting Piaget. For example, Dasen (1994) in a cross-cultural study noted that development for Aboriginal children differed when it came to the ability to conserve and their spatial awareness. This suggests that development may not be completely dependent on maturation but also on cultural influences as well. Within the classroom, a culturally responsive approach that also takes into account cognitive development according to Piaget would be a student-centered approach using differentiated instruction (Hamza & Hernandez de Hahn, 2012).

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Model provides further context for developing cognitive processes as a child’s microsystem expands in middle childhood when they enter school, creating new connections in the mesosystem between the child’s teacher and caregivers (Berk, 2000). Additionally, as a child’s world expands, reaching beyond the family unit in childhood, there are also realizations around mortality and a change in fears and potential phobias. Fears in particular tend to follow a developmental trajectory, an indication that they may be associated with cognitive development. For example, in infancy fears tend to be associated with maternal separation, whereas in middle childhood fears are often associated with getting injured physically (LoBue et al., 2019; Muris & Field, 2011).

Optional resources to further explore the above developing skills in middle childhood according to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development found in Figure 10.5 and 10.6.

Figure 10.5. Concrete Operations (Davidson Films, Inc.) [YouTube Video].

Figure 10.6. Overview: Seriation – A Developmental Issue | Monograph Matters 84.4 [YouTube Video].

10.2.3 Bandura

Albert Bandura (1925–2021), a leading contributor to social learning theory, felt that internal mental states play a role in learning and that observational learning (modeling) is much more complex than just imitating others (1977) (see Chapter 2). Adolescents struggling with their identity rely heavily on their peers to act as role models, observing their behaviors. Sometimes we do things because we’ve seen it pay off for someone else. We engage in the behavior because we hope it will pay off for us as well. Bandura (1986) suggests that reinforcement from the environment demonstrates that we are not just the product of our environment, rather this interplay highlights that we influence our surroundings as well. See Chapter 2 for more information on Bandura’s social learning theory.

What does Bandura’s social learning theory mean for development during middle childhood and academic learning? It is important for parents, caregivers, teachers, and other adult role models to consider and acknowledge what they are modeling, how the environment may be influencing learning, and the child’s motivation and self-efficacy related to a goal. Parents, caregivers, teachers, and other adult role models need to consider and acknowledge what they are modeling, how the environment may be influencing learning, and the child’s motivation and self-efficacy related to a goal. If you want your children to read, then read to them. Let them see your interest in books and reading. Keep books in your home. Talk about your favorite books. The same holds for qualities like kindness, courtesy, and honesty. The main idea is that children observe and learn from the world around them, so be consistent and toss out the adage “Do as I say, not as I do,” because children tend to copy what you do instead of what you say. Besides parents, many public figures, such as Martin Luther King, Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, are viewed as prosocial models who can inspire social change (Figure 10.7). Can you think of someone who has been a prosocial model in your life?

Figure 10.7. Image. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. San Francisco June 30, 1964.

The antisocial effects of observational social learning are also worth mentioning. There are certainly cases of intergenerational cycles of maltreatment within families, however the research is inconclusive with a wide range of outcomes for individuals who have witnessed or experienced abuse (Child Welfare Gateway, 2016). We can expect that empirically-based interventions to support families as well as mandatory reporting as an intervention has assisted in breaking these cycles.

Beyond witnessing in-person aggressive behavior; some studies suggest that violent television shows, movies, and video games may also have antisocial effects. Although research is looking more at the underlying mechanisms behind this. Further research needs to be done to understand the correlational and causational aspects of media violence and behavior (Bender et al., 2018).

10.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Theories

“Vygotsky” is remixed from “2.5: Exploring Cognition” which was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Laura Overstreet via source content and shared under a CC BY 4.0 license and “9.4: Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development” which was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Todd LaMarr and is shared under a mixed 4.0 license.

“Piaget” is remixed from “Human Behavior and the Social Environment I” by Susan Tyler and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Martin D. S. Braine. “Piaget on Reasoning: A Methodological Critique and Alternative Proposals.” Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 27, no. 2 (1962): 41–63. https://doi.org/10.2307/1165530.

“Bandura” is remixed from https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/lesson/15327/overview-old.

Figure 10.1. “School Children in Guatemala, Try a ‘Go with Gus’ Tour” by moonjazz is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 10.2. “Pint-size Zumba offered” by USAG-Humphreys is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.3. Image by OSC Admin is licensed by CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 10.4. Image by John Voo is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.7. “Martin Luther King, Jr. San Francisco June 30 1964” by geoconklin2001 is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 10.4. Understanding that ice cubes melt is an example of reversibility.

Figure 10.4. Understanding that ice cubes melt is an example of reversibility.