10.3 Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood

Cognitive skills continue to expand in middle and late childhood. Children in middle childhood are in the concrete operational stage of cognitive development according to Piaget’s stages of cognitive development theory. During this stage, children demonstrate thought processes that become more logical and organized when dealing with concrete information. Abstract thought has yet to develop. Children at this age understand concepts such as past, present, and future, giving them the ability to plan and work toward goals. Additionally, they can process complex ideas such as addition and subtraction and cause-and-effect relationships. The following section will further explore the expanding cognitive processes related to middle childhood including executive functioning, attention, and how environmental stressors can impact cognitive processing.

10.3.1 Executive Function

We all have moments where we struggle to pay attention or process information. This struggle could happen for a variety of reasons including diet, particular distractions, or genetics. Focus attention is one of the skills within the umbrella of executive functioning. Executive function describes the mental processes that enable a person to manage tasks and includes the ability to control attention, manage emotional reactions and behaviors, keep track of information, be self-aware, and organize thinking. Children need support to develop these skills and the range of support varies based on environmental and personal factors. As children enter school, they have increased opportunities to develop these skills. At the same time, children with low executive-functioning skills often struggle in school settings due to their inability to control behaviors essential for learning.

10.3.1.1 Impulse control

Impulse control is an executive-function skill that is essential in enabling children to function independently in social settings and learning environments. Impulse control allows children to prioritize tasks and manage certain behaviors. Most children in middle childhood would prefer to play instead of doing homework, but the ability to control the impulse to play makes it possible to sit down and focus on homework. For safety reasons, children typically begin practicing impulse control in early childhood. For example, a 4-year-old who stops themself from running into the street while chasing after a ball is practicing impulse control. During middle childhood, this skill is still developing and additional support continues to be needed for successful outcomes. Executive function skills, such as impulse control continue to develop through middle childhood and beyond adolescence, as processes in the brain develop from the back to the front. The prefrontal cortex, the last area to develop, is the area of the brain that handles the ability to control impulses (Sebastian et al., 2014). This can be challenging for parents and caregivers, and it is important for adults to remember the critical role they contribute in supporting these developing cognitive skills through scaffolding and modeling (Bandura, 1993).

A child who has not yet developed impulse control may exhibit certain behaviors or characteristics which may include an inability to sustain attention, poor time management, and becoming easily distracted. Children who have difficulty controlling impulses may also be labeled as hyperactive, which is characterized by excessive movement, fidgeting, getting up out of their seat when they are expected to be sitting, blurting out or speaking over others, or difficulty waiting their turn.

10.3.1.2 Emotional regulation

Healthy emotional regulation is the ability of a child to acknowledge an emotion and be able to handle emotional reactions and behaviors in useful ways. Several areas of the brain work together to help with emotional regulation, including the amygdala, prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, hippocampus, and basal ganglia (Raschel et al., 2016). Emotional regulation is still developing during middle childhood , and children will need support to successfully develop this skill. This is not a cognitive skill that can be perfected without practice. One way to support the development of skillful emotional regulation is to model and encourage healthy coping strategies such as practicing or preparing for a situation, breathing exercises, or visualization techniques. Coping strategies are often connected to particular emotions and contexts. For example, a coping strategy at school may be to find an adult to help navigate the fear of a school bully, but at home, the coping strategy for the same fear may include playing outside with a pet. In addition to positive coping strategies, emotional intelligence, including the ability to recognize and understand emotions is important in developing the ability to manage emotions in healthy, useful ways.

It is important to remember that children who have trouble controlling their emotions are having a challenging time and are not bad kids. All children in middle childhood have executive functioning skills which are still developing. This can be challenging for teachers, caregivers, parents, and peers, and taxing on their emotional regulation. Even adults must practice healthy coping strategies. Reaching for a bowl of ice cream every time you are feeling overwhelmed may be a coping strategy, but it is not a healthy long term strategy!

Adults modeling positive coping strategies can promote the development of healthy emotional regulation in children, however the opposite is also true. Unhealthy coping strategies modeled by adults, or dysregulated emotional environments, can negatively influence the development of healthy emotional regulation. This explains why children from adverse experiences or environments can be especially overwhelmed and challenged by executive-functioning skills including emotional regulation (Milejovich, Machlin, and Sheridan, 2020). Providing a safe and predictable environment, and modeling positive coping strategies can help children use the executive-functioning skills they have at any particular moment.

Take a moment and think about what your coping strategies might be. Do you have different strategies for when you are sad, frustrated, or overwhelmed? Are the strategies only available at home? Are these strategies healthy or unhealthy?

10.3.1.2.1 Optional resources:

Figure 10.8. Why Practicing Can Help with Emotional Regulation [YouTube Video].

Emotion researcher Marc Brackett has led the scientific research team that helped develop an app to help track emotions and understand emotions. To find out more or download the free app: https://howwefeel.org/.

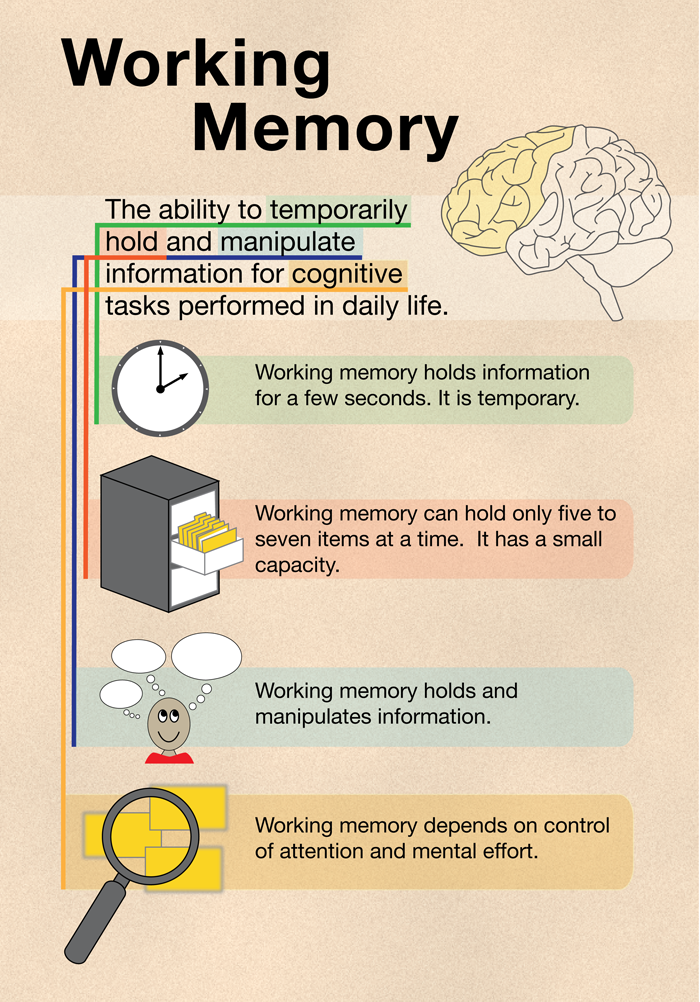

10.3.1.3 Working Memory

During middle childhood, children improve the capacity of their working memory and their use of memory strategies. Illustrated in Figure 10.9, working memory is the ability to temporarily hold a small amount of information for cognitive tasks (Cowan, 2014). This is different from long-term memory, which is a large bank of information saved from one’s life. Research suggests that both the increase in processing speed and the ability to keep irrelevant information from entering memory contribute to greater efficiency of working memory during middle childhood (Figure 10.9) (de Ribaupierre, 2002). Changes in myelination and the increased synaptic pruning within the cortex from preschool through middle childhood are likely behind the increase in processing speed and ability to filter out irrelevant information (Kail et al., 2013).

Figure 10.9. Working memory expands during middle and late childhood.

Children with learning disabilities in math and reading often have difficulties with working memory (Alloway, 2009). They may struggle with following the directions of an assignment. When a task calls for multiple steps, children with poor working memory may miss steps because they lose track of where they are in the task (Figure 10.11). Adults can support children who are struggling with working memory by using more familiar vocabulary, using shorter sentences, repeating task instructions more frequently, and breaking more complex tasks into smaller, more manageable steps. Some studies have also shown that using more intensive working memory strategies like dividing larger learning and memory tasks into smaller activities, or chunking can aid in improving the capacity of working memory (Alloway et al., 2013).

Figure 10.10. Children study in the public school, Luciliio Da Souza Reis in Juliana in the Amazon region of Brazil near Manaus. Brazil. Photo: © Julio Pantoja / World Bank.

10.3.1.4 Self-awareness

Children in middle and late childhood have increased self-awareness. Children at this stage of development have a better understanding of the level of difficulty and their abilities in task performance. As school-aged children become more realistic about their present abilities and the time required to accomplish a task, they can adapt studying strategies accordingly, whereas a child with a lack of self-awareness would need support. For example, in preparation for a spelling bee, a child with increased self-awareness may spend more time practicing words they do not know how to spell, whereas a child with less self-awareness would not prioritize based on ability (or lack of). This ability to gauge which tasks are important to focus on versus those that are not, is an example of self-awareness or metacognition.

Self-awareness is the knowledge we have about our thinking, and our ability to use this awareness to regulate our cognitive processes. Critical thinking, or a detailed examination of beliefs, courses of action, and evidence, involves teaching children how to think. The purpose of critical thinking is to evaluate information in ways that help us make informed decisions. Critical thinking involves better understanding of a problem through gathering, evaluating, and selecting information, and by considering many possible solutions. Ennis (1987) identified these skills as useful in critical thinking: analyzing arguments, clarifying information, judging the credibility of a source, making value judgments, and deciding on an action. Self-awareness is essential to critical thinking because it allows us to reflect on the information as we make decisions.

10.3.1.4.1 Optional resource:

According to Bruning et al. (2014), there is a debate in American education as to whether schools should teach students what to think or how to think. The video below is from a researcher who focuses on thinking and knowledge. He has some criticisms about direct instruction, meaning through lectures or demonstrations rather than active engagement or problem-solving. Based on middle childhood cognitive development and this video, what are solutions for “over-engineered education”?

Figure 10.11. TEDxWilliamsport – Dr. Derek Cabrera – How Thinking Works [YouTube Video].

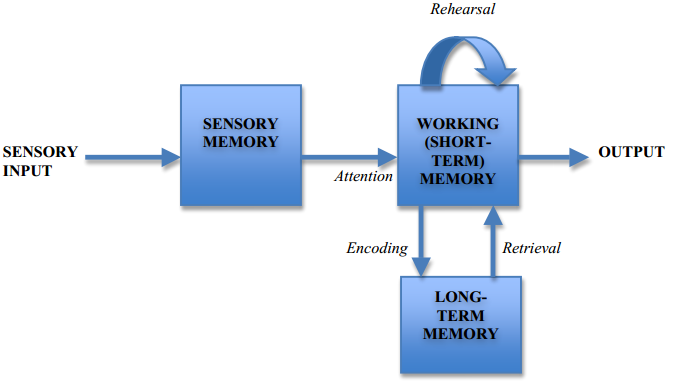

10.3.1.5 Information Processing

During middle childhood, children become better at learning and remembering because their brains are better at processing and storing information. At this age, they develop more categories for concepts and learn more efficient strategies for storing and retrieving information. They are also able to learn from past experiences. New experiences are similar to old ones or remind the child of something else they already know. This helps them process new experiences more easily. Information processing theory compares how the mind processes memories to the way that computers store, process, and retrieve information. There are three levels of memory: sensory memory, working memory, and knowledge base.

Figure 10.12. AwesomeNikk, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Sensory memory is a short-term storage of sensory information that is acquired from the environment, for example, how something feels, looks, smells, or tastes. Information first enters our sensory memory (Figure 10.12). Stop reading and glance around the room very quickly. (Yes, really. Do it!) Okay. What do you remember? Chances are, not much. In that quick glance, everything you saw and heard entered into your sensory memory. Although you might have heard yourself sigh, caught a glimpse of your dog walking across the room, or smelled the soup on the stove, you did not store those sensations. Sensations are always entering your brain and yet most of these sensations are never stored there. They are lost because your brain immediately filtered them out as irrelevant. If the information is not perceived or stored, it is discarded quickly. If not discarded, information may be encoded for long-term memory such as recognizing a particular color, for example recognizing that stop signs are red.

If information is meaningful, it enters our working memory (See working memory pg. 22). All of the things on your mind at this moment are part of your working memory. There is a limited amount of information that can be kept in the working memory at any given time, and any extra information can be lost. Have you ever missed information in class because the instructor speaks too quickly for you to get it all in your notes? Information in our working memory must be stored effectively in our knowledge base to be accessible for later use.

The knowledge base level of memory has an unlimited capacity and stores information for days, months, or years. It’s also called long-term memory and is where you ultimately want information to be stored. Effectively storing memory requires organizing information in a meaningful way for later retrieval.

10.3.2 Attention

Beginning at birth our reflexes allow us to respond and attend to environmental stimuli. These primitive reflexes are the beginning of higher-order executive functions like attention. Attention, holistically, is a person’s cognitive ability to process or inhibit information in their environment. Attention continues to develop in middle childhood, including a sharp improvement in selective attention from age six into adolescence (Vakil et al., 2009). Selective attention is the ability to focus on specific information even if there is other information being processed at the same time. For example, a student who can listen to a teacher reading a story to the class while other students seated behind them are giggling is using selective attention (Figure 10.13) to remain focused on the story and ignore the giggling.

Figure 10.13. Samdarche, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons.

Children in middle childhood also improve their ability to shift their attention between tasks or different features of a task (Carlson et al., 2013). A child in preschool who is asked to sort objects into piles based on type of object may struggle if you switch to asking them to sort based on color because they’d have to forget the previous rule of sorting by type. A school-aged child often has less difficulty making the switch because they are more flexible in their ability to divide or alternate attention. These changes in attention and working memory contribute to children having more strategic approaches to challenging tasks. Children can become more efficient learners and be able to tolerate classroom instruction for longer periods.

10.3.2.1 What is “normal”?

Not all children in middle childhood experience the same expansion of attention capacity. Attention is more complex than the ability to sustain focus. Research is revealing more about the variances in attention and differences in cognition every day. Rather than assuming that there is a “normal” amount of sustained attention that kids should have, it is best to assume that there is a wide range of abilities when it comes to attention. Also, the environment plays an important role in the capacity for attention at any given moment.

10.3.2.2 Understanding Variations in Attention

There is variation in the ability to multitask or pay attention to the smallest of details. While there is research to support that attention increases with age (Hagen & Hale, 1973), it is also true that the range of and variation in attention is wide. As with all children, individuals with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), or those who are on the autism spectrum may benefit from a variety of environmental or task-oriented supports. Such supports may include visual schedules, visual timers, checklists, or focus-enhancing tools that children can fidget with such as modeling clay, silly putty, or exercise balls to sit on. Often these cognitive differences are attributed to a lack of attention, but for some individuals, there may be a tendency for hyper-attention versus a lack of attention.

10.3.2.3 Strategies for Success

As school-aged children become more aware of their thinking and cognitive abilities, there is also a progression in the development and use of memory strategies (Bjorklund, 2005). Examples of memory strategies include rehearsing information you wish to recall, visualizing and organizing information, creating rhymes, or inventing acronyms. Children in elementary school have a steady increase in the use of memory strategies, though there can be considerable individual differences at each age (Schneider et al., 2009). Children who utilize more strategies have been found to have better memory performance than their peers of the same age (Schneider et al., 2009). Yet, some school-aged children may experience difficulties or a deficiency in their use of memory strategies. Therefore, understanding where school-age children may have difficulty in the use of a memory strategy can be useful in supporting their ability to recall important information. Memory strategy deficiencies to be aware of are described below.

A mediation deficiency occurs when a child does not grasp the strategy being taught and so they do not benefit from its use. If they do not understand why using an acronym might be helpful, or how to create an acronym, the strategy is not likely to help them.

In a production deficiency, the child does not spontaneously use a memory strategy and must be prompted to do so. In this case, children know the strategy and are capable of using it, but they fail to “produce” the strategy on their own. For example, children might know how to make a list but may fail to do this to help them remember what to bring on a family vacation.

A utilization deficiency is one where a child uses an appropriate strategy, but it fails to aid their performance. Utilization deficiency is common in the early stages of learning a new memory strategy (Schneider & Pressley, 1997; Miller, 2000). Until the use of the strategy becomes automatic, it may slow down the learning process, as space is taken up in memory by the strategy itself. Initially, children may get frustrated because their memory performance may seem worse when they try to use the new strategy. Once children become more adept at using the strategy, their memory performance will improve. Sodian and Schneider (1999) found that new memory strategies acquired before age 8 often show utilization deficiencies with there being a gradual improvement in the child’s use of the strategy. In contrast, strategies acquired after this age often followed an “all-or-nothing” principle in which improvement was not gradual, but abrupt.

Additional strategies to help restore, increase, or sustain attention include:

- Care for overall health, including sleep and nutrition (Kirszenblat & van Swinderen, 2015)

- Mindfulness exercises (Norris et al., 2018)

- Spending time outside (Amicone et al., 2018; Moran, 2019)

- Avoidance of multitasking (Srna et al., 2018)

10.3.2.3.1 Optional resource:

Figure 10.14. The Trouble with Normal: My ADHD the Zebra | Emily Anhalt | TEDxSyracuseUniversity [YouTube Video].

10.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood

“Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood” remixed from Weiss Understanding the Whole Child, Introduction to Cognitive Development in Middle Childhood.

Figure 10.9. Image by Anchor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.