10.4 Language Development in Middle Childhood

The development of language is complex. Language involves both the ability to process and understand spoken and written words and to communicate when we speak or write. Most languages are spoken. Speaking involves a variety of complex cognitive, social, and biological processes including the operation of vocal cords and the coordination of breath with movements of the throat, mouth, and tongue. Other languages are unspoken sign languages, which use hand movements. The most common being American Sign Language (ASL). ASL is currently spoken by more than 500,000 people in the United States alone (Mitchell et al., 2006).

10.4.1 Growing Minds, Expanding Language

Beyond communication with others, language also makes it possible to access existing knowledge, draw conclusions, set and accomplish goals, and understand complex social relationships. Language is fundamental to our ability to think, and without it, we wouldn’t be as intelligent as we are.

Language can be conceptualized in terms of sounds, meaning, and the environmental factors that help us understand it. Understanding how language works means reaching across many branches of psychology—everything from basic neurological functioning to high-level cognitive processing. Language shapes our social interactions and brings order to our lives. Complex language is one of the defining factors that make us human.

10.4.1.1 Complex Syntax

Children in middle childhood can classify objects in many ways because of their expanded vocabulary. By fifth grade, a child’s vocabulary has grown to 40,000 words. Vocabulary grows at a faster rate during middle childhood than during any other developmental period. This language explosion differs from early childhood since school-age children are able to associate new words with those already known. Kids in middle and late childhood are also able to think of objects in less literal ways. For example, if asked for the first word that comes to mind for “pizza,” the younger child is likely to say “eat” or another word that describes what is done with a pizza. However, the older child is more likely to place pizza in the appropriate category and say “food.” Older children also love to tell jokes. They may use jokes that involve wordplay such as knock-knock jokes or jokes with punchlines. Young children do not understand wordplay and tell jokes that are literal or slapstick, such as, “A man fell in the mud! Isn’t that funny?”

10.4.1.2 Metalinguistic Development

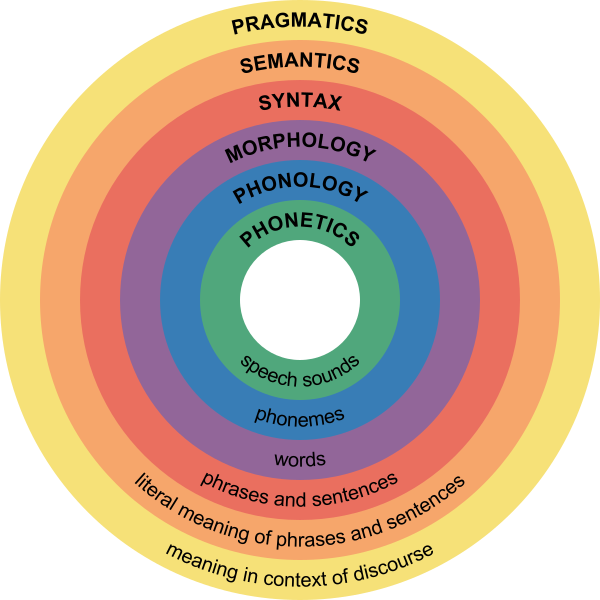

Language is such a special topic that there is an entire field called linguistics that is devoted to its study. Linguistics views language objectively, using the scientific method and rigorous research to form theories about how humans acquire, use, and sometimes abuse language. There are a few major branches of linguistics useful to understand language from a psychological perspective. Figure 10.15 illustrates the various subfields of linguistics, including phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and pragmatics (Figure 10.15).

Figure 10.15. Major branches of linguistics. (Image is in the public domain).

When learning languages in middle childhood, children understand that communication includes many complex parts like comprehension, fluency, and meaning. Every language has rules which act as a framework for meaningful communication. People fill this framework with words. Every human language has a lexicon, which is the total of all of the words in that language. By using grammatical rules to combine words into logical sentences, humans can convey an infinite number of concepts.

While every language has a different set of rules, all languages obey rules which are called grammar. Speakers of a language have internalized the rules and exceptions for that language’s grammar. There are rules for every level of language that include word formation, phrase formation, and sentence formation. For example, native speakers of English have internalized the general word formation rule that -ed is the ending for past-tense verbs, so even when they encounter a brand-new verb, they automatically know how to put it into past tense. Additionally, when you use the verb “buy,” you know because of phrase formation that the verb needs a subject and an object; “She buys” is wrong, but “She buys a gift” is okay. Older children can learn new rules of grammar with more flexibility. While younger children are likely to be reluctant to give up saying “I goed there,” older children are quick to adjust to fit the rules of their spoken language.

Words don’t have fixed meanings but change based on the spoken context. We use contextual information that surrounds the language to help interpret meaning. Context includes tone of voice, body language, and the words being used. For example, when said with a big smile, the word “awesome” means the person is excited about a situation. When said with crossed arms, rolled eyes, and a sarcastic tone, “awesome” means the person is not thrilled with the situation. In middle childhood, many children are aware of the contextual clues important to communication and are expanding their language development. Additionally, many students are expanding their language development through more than one language.

10.4.2 Dual-language Instruction

Although one-language speakers often do not realize it, more than half of the world’s population is bilingual (Grosjean, 2020), meaning that they understand and use two languages. While the United States is still largely monolingual, with English defining the norm in the classroom (Cioè-Peña, 2021), the diversity of languages other than English spoken at home has increased to 20% of the US population (Dietrich & Hernandez, 2022). Three-quarters of bilingual students are Hispanic, but the remaining quarter represents more than 100 different language groups from around the world. In larger communities throughout the United States, it is common for a single classroom to contain students from several language backgrounds at once. In classrooms, as in other social settings, bilingualism exists in different forms and degrees. The student who speaks both languages fluently has a definite cognitive advantage. A fully fluent bilingual student is in a better position to express concepts or ideas in more than one way, and to be aware of doing so (Jimenez et al., 1995; Francis, 2006). Having a large vocabulary in a first language has been shown to save time in learning vocabulary in a second language (Hansen et al., 2002).

Cultures and ethnic groups differ not only in languages but also in how languages are used. Since some of the patterns differ from those typical of modern classrooms, they can create misunderstandings between teachers and students (Cazden, 2001; Rogers, et al., 2005). Consider these examples and imagine how they might be interpreted in the classroom:

- It may be considered polite or even intelligent not to speak unless you have something important to say. Small talk is considered immature in some cultures (Minami, 2002).

- Eye contact varies by culture. In many Black and Latino communities, it is considered inappropriate for a child to make direct eye contact with an adult who is speaking to them (Torres-Guzman, 1998).

- Social distance varies by culture. It may be common to stand relatively close when having a conversation, but not with others (Beaulieu, 2004).

- Wait time varies by culture. Wait time is the gap between the end of one person’s comment or question and the next person’s reply or answer. In some cultures, wait time is relatively long, as long as 3 or 4 seconds (Tharp & Gallimore, 1989). In others it is a negative gap, meaning that it is acceptable, even expected, for a person to interrupt before the end of the previous comment.

10.4.2.1 Theories of Language Development

Humans, especially children, have an amazing ability to learn a language. Within the first year of life, children will have learned many of the necessary concepts to have functional language, although it will still take years for their capabilities to develop fully. As we just explained, some people learn two or more languages fluently and are bilingual or multilingual. Here is a recap of the theorists and theories that have been proposed to explain the development of language, and related brain structures, in children.

10.4.2.2 Skinner and Operant Conditioning

B. F. Skinner believed that children learn language through operant conditioning; in other words, children receive “rewards” for functionally using a language. For example, a child learns to say the word “drink” when she is thirsty; she receives something to drink, which reinforces her use of the word for getting a drink, and thus she will continue to do so. This follows the four-term contingency that Skinner believed was the basis of language development—motivating operations, discriminative stimuli, response, and reinforcing stimuli. Skinner also suggested that children learn language through imitation of others, prompting, and shaping.

10.4.2.3 Chomsky and Language Acquisition

Noam Chomsky’s work discusses the biological basis for language and claims that children have innate abilities to learn a language. Chomsky terms this innate ability as the “language acquisition device.” He believes children instinctively learn a language without any formal instruction. He also believes children have a natural need to use language, and that in the absence of formal language children will develop a system of communication to meet their needs. He has observed that all children make the same type of language errors, regardless of the language they are taught. Chomsky also believes in the existence of a “universal grammar,” which posits that there are certain grammatical rules all human languages share. However, his research does not identify areas of the brain or a genetic basis that enables humans’ innate ability for language.

10.4.2.4 Piaget and Assimilation and Accommodation

Jean Piaget’s theory of language development suggests that children use both assimilation and accommodation to learn language. Assimilation is the process of changing one’s environment to place information into an already-existing schema (or idea). Accommodation is the process of changing one’s schema to adapt to the new environment. Piaget believed children need to first develop mentally before language acquisition can occur. According to him, children first create mental structures within the mind (schemas) and from these schemas, language development happens.

10.4.2.5 Vygotsky and Zone of Proximal Development

Lev Vygotsky’s theory of language development focused on social learning and the zone of proximal development (ZPD). The ZPD is a level of development obtained when children engage in social interactions with others; it is the distance between a child’s potential to learn and the actual learning that takes place. Vygotsky’s theory also demonstrated that Piaget underestimated the importance of social interactions in the development of language. Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s theories are often compared with each other, and both have been used successfully in the field of education.