13.2 Theories

Understanding how teenagers think and their cognitive development is no easy task! Cognitive theories in adolescent development can provide a framework or set of statements that allow researchers, educators, and scientists to describe, explain, and predict outcomes or behaviors (see Chapter 2 for more information on theory). Understanding cognitive development through tested theories can help inform programs and policies impacting children in this developmental period.

Throughout the developmental period referred to as adolescence, cognitive processes continue expanding. As with any theory, a cognitive theory provides an empirically tested perspective to the understanding of how cognitive processes occur.

13.2.1 Piaget

Chapter 2 introduced Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development and how Piaget believed that humans develop in stages. As children make sense of the world around them, building upon previous knowledge, they progress through four stages of cognitive development. The fourth stage of cognitive development according Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is the formal operational stage.

13.2.1.1 Formal Operational Stage

The formal operational stage of cognitive development is from approximately 12 years old and into adulthood. Children’s understanding and ability to make sense of the world moves beyond just what can be seen or observed. In adolescence, young people often are able to think more abstractly. Adolescents can think and discuss abstract concepts such as beauty, love, freedom, and morality. Yet even in adulthood the hallmark of this developmental stage, the ability to think abstractly, may not be constant. Formal schooling may stop for some at the age of eighteen, but exercising our cognitive abilities should not. Cognitive plasticity, or the ability for the brain and cognitive abilities to change over time, can cause some people to be less flexible in their thinking, falling back to concrete operational ways of thinking. Neural pathways can be created throughout our lifetime if we keep flexing our ability to do so.

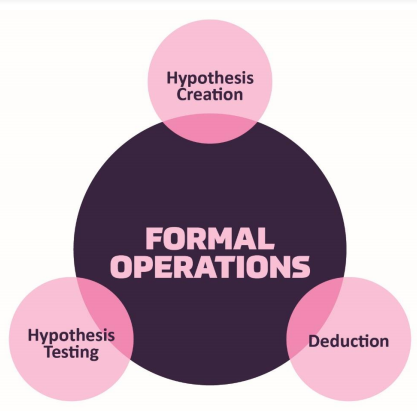

Figure 13.1. Formal Operations by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Additional cognitive skills developed during the formal operational stage include the ability for hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which means that young people at this stage can develop a hypothesis based on what they think will logically occur (Figure 13.1). This hypothetical, what-if thinking is important for scientific thinking. Formal operational thinkers are able to think about potential outcomes and then test their hypothesis systematically. Additionally, adolescents have developed the concept of transitivity, or understanding the relationship between two objects. Transitivity allows adolescents to build on previous knowledge and problem-solve. For example, when asked: If Maria is shorter than Alicia and Alicia is shorter than Caitlyn, who is the shortest? The following video (Figure 13.2) illustrates the capability of deductive reasoning in different stages of cognitive development.

Figure 13.2. Piaget – Stage 4 – Formal – Deductive Reasoning [YouTube Video].

13.2.1.2 Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

Educational experiences, both in and out of the classroom are important in developing abstract cognitive abilities. The day-to-day educational opportunities at school make schooling the main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. Guided learning through hypothetical problems posed by teachers encourages adolescents to reason, and apply the what-if, hypothetical thinking to problem-solve. Students move beyond basic understanding when they apply hypothetical reasoning and are able to create alternative explanations. Hypothetical thinking also provides students the opportunity to broaden their understanding of other people’s experiences. For example, a social studies teacher using hypothetical-based pedagogy may ask students to imagine what it would be like to be enslaved during colonialism and write about their experience. Students have to apply what-if reasoning to narrate a hypothetical situation.

Piaget’s research on hypothetical reasoning often focused on scientific reasoning and problem-solving (Figure 13.3). The ability to systematically test and manipulate mental models of objects or processes is the precise skill that defines formal operations.

Figure 13.3. Image by JustGrimes Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Students who are able to think hypothetically have an advantage as they require relatively few “props” to solve problems when completing schoolwork and can be more self-directed. This does not mean that academic success is out of reach for students who may not have this cognitive ability or that formal operational thinking guarantees academic achievement. All students have varying needs and strengths and success is achieved when there is guided support along their educational journey.

13.2.1.3 Adolescent Egocentrism

During adolescence individuals often demonstrate egocentrism or a heightened self-focus. Adolescent egocentrism is characterized by adolescents obsessing that others are focused on how they look, judging their appearance or that people are constantly focused or judging what they say and do. For example, adolescents may spend a considerable amount of time checking for responses or likes to a social media post, or an adolescent may be more withdrawn socially with growing concerns about what others think of them (Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4. Image by Christian Hornick Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA 2.0).

While Piaget coined the term egocentrism to describe how children center themselves and their needs, it was David Elkind (1967) who expanded egocentrism theorizing adolescent perceptions of self. Elkind theorized that the physical changes from puberty lead to the hyperfocus on appearance and behavior. Likewise, adolescents think others are as hyperfocused on them as they are of themselves. According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in the imaginary audience and the personal fable.

The belief that others are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance results in the adolescent anticipating the reactions of others, and consequently constructing an imaginary audience. The imaginary audience describes when individuals tend to see themselves as the object of attention. They feel as if they are always on stage and under the scrutiny of others. This false perception of attention may be interpreted as being vain, but Elkind thought that the imaginary audience contributed to the self-consciousness that occurs during early adolescence. For example, it may be difficult for a pre-teen to think that no one notices a small pimple on their face. It is more likely that they imagine that everyone they speak to, walk by, or see is staring at the pimple on their face and thinking that they are “gross.”

Personal fable is another example of biased thinking that occurs during adolescence. Personal fable describes when adolescents tend to see themselves as unique or even invulnerable. Elkind explains that because adolescents feel like they are the center of attention (imaginary audience), they regard themselves and their feelings as being special and unique. Adolescents may believe that they are the only ones who experience such strong emotions. Perhaps you can recall during this stage of development feeling as if no one understood what you were experiencing. Most adolescents have exclaimed at one time or another, “You just don’t understand my life”! The concept of personal fable and belief of uniqueness is what encourages adolescents to think they can handle or do anything. They see themselves as invulnerable to the consequences that other people may have succumbed to. Research suggests that this is what removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016) and to make decisions that could be serious health risks (Banerjee et al., 2015). Adolescents may be prone to engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or having unprotected sex, because they believe they are invincible. These skewed, biased thoughts typically decline as individuals move into late adolescence, as they gain a greater understanding of themselves and the world around them.

13.2.1.4 Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

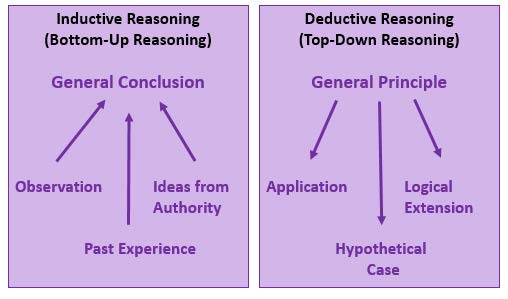

Inductive reasoning is the first type of reasoning to emerge in childhood. Inductive reasoning is sometimes characterized as “bottom-up processing” in which specific observations, or comments from those who are perceived to be knowledgeable, may be used to draw general conclusions. These conclusions may or may not be accurate. For example, a kindergartner watches his older brother and other middle schoolers in the neighborhood ride the bus to school. The kindergartner makes the conclusion that all middle schoolers ride the bus to school. In contrast, deductive reasoning, sometimes called “top-down-processing,” should emerge in adolescence. Deductive reasoning begins with a general principle that then leads to proposed conclusions. For example, if a general theory maintains that all trees are green and then asks what color do you expect a particular tree to be, deduction would say the tree should be green. You begin with a general principle that has been observed to be true (trees are green), the pattern of this observation is recognized (that all trees are green), so the application and logical extension of this principle tells you that you can expect a particular tree to also be green (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5. Inductive and Deductive Reasoning (Image Source: Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, CC BY NC SA).

As adolescents are now able to think abstractly and hypothetically, they exhibit many new ways of reflecting on information (Dolgin, 2011). For example, they demonstrate greater introspection or thinking about one’s thoughts and feelings. They begin to imagine how the world could be, which leads them to become idealistic or insisting upon high standards of behavior. Because of their idealism, they may become critical of others, especially adults in their life. Additionally, adolescents can demonstrate hypocrisy, or pretend to be what they are not. Since they are able to recognize what others expect of them, they will conform to those expectations for their emotions and behavior seemingly hypocritical to themselves. Lastly, adolescents can exhibit pseudostupidity, which is when they approach problems at a level that is too complex and they fail because the tasks are too simple. Their new ability to consider alternatives is not completely under control and they appear “stupid” when they are in fact bright, just inexperienced.

13.2.2 Vygotsky

Unlike Piaget, Vygotsky did not subscribe to the idea of developmental stages, rather he argued that development was cumulative and not a result specific to maturation (see Chapter 2 for more on Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory). According to Vygotsky, there are critical periods of cognitive growth, and in adolescence, development of one’s own culture and beliefs occurs. Vygotsky believed that cultural tools support the development of reasoning and problem-solving skills as well as adolescents’ own “cultural tool kit.”

Figure 13.6. “Sarajevo, Bosnia” by Kashklick is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

13.2.2.1 Cultural Tools

According to his sociocultural theory, Vygotsky believed that development was a result of social interactions. Beyond interactions with people, these social interactions also included cultural artifacts such as language, signs, and symbols (Figure 13.6). In adolescence, these influences, which Vygotsky referred to as cultural tools, provided context, integration, or even intersected with the development of one’s own culture. The mental processing from these social interactions supported Vygotsky’s belief that cultural tools also provide opportunities for cognitive development. Vygotsky believed that adolescents develop increased cognitive abilities such as focused attention, memory, formal reasoning and verbal thinking from social interactions. The cultural tool of language is emphasized by Vygotsky as important for cognitive development. According to Vygotsky (1962), language plays two important roles in cognitive development. Those roles are:

- The transmission of information by adults to children.

- A cultural tool that provides opportunities for cognitive adaptation.

13.2.2.1.1 Vygotsky in the classroom

Reciprocal teaching is a contemporary teaching approach based on Vygotsky’s work. Reciprocal teaching is when students and teachers collaborate in the learning process, with the teacher’s role diminishing over time. With reciprocal teaching, students deepen their understanding and gain confidence in their learning when they explain to and receive feedback from others. Research has shown that students can develop their math skills and their social awareness & relationship skills by taking on the roles of coach and player as they explore math concepts and problems with a partner. Follow this link to Digital Promise for more information including a short video of how this is applied for middle to high school mathematics: https://lvp.digitalpromiseglobal.org/content-area/math-7-10/strategies/reciprocal-teaching-math-7-10/summary

13.2.2.2 Spontaneous and Scientific Thinking

The development of abstract, hypothetical thinking in adolescence is relevant to Vygotsky’s beliefs on both spontaneous thinking and scientific thinking. According to Vygotsky, spontaneous concepts are based on experiences, similar to inductive reasoning. Vygotsky believed that it is these everyday experiences, the spontaneous thinking, that pave the way for scientific thinking through reflection and cultural tools such as language, writing, and numbers.

13.2.2.3 Critical Periods

Vygotsky ascribed to what he called critical periods. These critical periods were developmental periods of transition and cognitive restructuring. Vygotsky did not see these periods as periods of growth, rather periods of “constructive processes of development” (Vygotsky, 1998, p. 194). The final critical period, according to Vygotsky, was in adolescence around the age of thirteen. This adolescent critical period is characterized by the change from concrete to abstract thought, as well as the shift away from fantasy play common in younger children. Vygotsky valued the role of play throughout development, yet acknowledged how it differed from early childhood and middle childhood in that there was a clear division in pretend and reality and games with rules became the play of adolescents.

13.2.3 Gaps and limitations

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that cognitive development is complete by the age of 12, however most recent research demonstrates that this developmental period of adolescence is one of important cognitive increases. Further, structurally cognitive development reaches a peak, but functionally, cognitive development can continue throughout one’s lifetime. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is vague in understanding mechanisms and processes, but it created the building blocks for empirical research on cognitive development and neuroscience today. Similar to Piaget, Vygotsky is vague to describe the critical period in adolescence. There is no identified mechanism that causes the cognitive restructuring during this developmental period.

13.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Theories

“Theories” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Piaget” is remixed and adapted from 14.3: Cognitive Theorists- Piaget, Elkind, Kohlberg, and Gilligan is shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson (College of the Canyons); 6.6: Cognitive Development in Adolescence is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Martha Lally & Suzanne Valentine-French; Lifespan Development by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted; and Psychology Through the Lifespan by Alisa Beyer and Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Vygotsky” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0 excluding “Vygotsky in the classroom” text box which is adapted from Reciprocal Teaching by Digital Promise and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License

“Gaps and Limitations” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Images

Figure 13.1. Formal Operations by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 13.3. Image by JustGrimes Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Figure 13.4. Image by Christian Hornick Attribution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Figure 13.5. Inductive and Deductive Reasoning (Image Source: Lifespan Development by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, CC BY NC SA).

Figure 13.6. “Sarajevo, Bosnia” by Kashklick is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.