13.3 Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Cognitive skills continue to expand in adolescence, while each child develops at their own rate, including their ability to think abstractly and in increasingly complex ways.

Adolescents will develop their own worldview, influencing their thinking and metacognition. We know that adolescents are in the formal operational stage of cognitive development. During adolescence, teenagers move beyond concrete thinking and become capable of abstract thought. Teen thinking is also characterized by the ability to consider multiple points of view, imagine hypothetical situations, debate ideas and opinions, and form new ideas. In addition, it’s not uncommon for adolescents to question authority or challenge established societal norms. The following section will further explore the expanding cognitive processes related to adolescence including executive functioning, attention, and how environmental stressors can impact cognitive processing.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model provides further context for developing cognitive processes as a child’s microsystem further expands during this period as they begin to plan and make strides toward adulthood. Adolescents may begin driving, working, registering to vote, getting involved with social or political concerns, enlisting in the military, or planning for college or vocational school. Additionally, a teen’s microsystem begins shifting away from their immediate family as peers and romantic interests play a larger role in their lives.

13.3.1 Executive Functioning

Executive functions like attention, increases in working memory, and cognitive flexibility have been steadily improving since early childhood. Studies have found that executive function is very competent in adolescence. However, self-regulation, or the ability to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self-regulation is especially true when there is high stress or high demand on mental functions (Luciano & Collins, 2012). While high stress or demand may tax even an adult’s self-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent brain may make teens particularly prone to more risky decision-making under these conditions. Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in five areas during adolescence: attention, memory, processing speed, organization, and metacognition.

- Attention: improvements in both selective attention and divided attention.

- Memory: improvements in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing speed: improves sharply between age 5 and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood.

- Organization: improved awareness of their thought processes and use of mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently.

- Metacognition: improved ability to think about thinking itself, including the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

13.3.1.1 Activity: Information Processing Model

In previous chapters, the information processing model was discussed. Memory will continue developing as well as the skills to acquire new information. Here is a video to review how information is processed, types of memory, and how this relates to cognitive development during this period of development.

Figure 13.7. Information processing model: Sensory, working, and long term memory | MCAT | Khan Academy [YouTube Video].

13.3.1.2 Metacognition

Thinking about thinking is referred to as metacognition. Adolescents become more reflective and can understand complex relationships between ideas and people. Metacognition abilities vary among adolescents and adults based on the capacity to evaluate situations objectively. Adolescents are better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. The ability to be introspective may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus.

Neuroimaging shows that different areas of the brain are responsible for cognitive processing and emotional processing (Brock et al., 2009). Cognitive processes are called “cool EF” (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Examples of cool EF are executive functions like attention, metacognition, problem-solving, and working memory. Emotional processes are called “hot EF” (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Hot EF relates to self-control, self-regulation, impulsivity, perspective-taking, and engagement in inappropriate versus appropriate behavior (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018).

Biological and behavioral development support the notion that the hot and cool EF trajectories are different. Frontal cortex development and myelination continue through adolescence (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018, p. 262). Neural pathways and brain areas associated with emotion regulation develop later than other systems, supporting the idea that the cool EF system comes on board before the hot EF system (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018, p. 262; Brock et al., 2009). One study found that when they switched the construct from a “hot” representation (emotionally charger) to a “cooler” representation (more neutral), it was much easier for the children to engage with and be successful at the task (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). These findings suggest that having to operate from the hot system places greater demands on the child. It is a more difficult system to utilize and it takes longer to develop (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Having an awareness of children’s hot and cool EF systems is important for understanding how best to interact with them, both personally or professionally, such as in an educational setting.

While metacognition is still developing throughout adolescence, it typically peaks just after late adolescence, making it a useful strategy for learning in and out of school (Hitomi dos Santos Kawata et al., 2021). Out of the classroom in everyday decision-making, metacognition allows adolescents to discern information as helpful or misleading (Moses-Payne et al., 2021). In the classroom metacognition assists in learning. Practices in the classroom can help students achieve agency over their learning and allows students to transfer learned information across varying contexts. Classroom practices to support metacognition include:

- Clear learning goals.

- Motivational strategies for deferred gratification.

- Scaffolding or progression in instruction.

- Model the use of metacognitive strategies (e.g., think aloud).

- Reciprocal teaching.

- Encourage reflection and evaluation.

13.3.1.3 Pruning

Adolescence is one of the few times that the brain is rapidly producing a large number of brain cells, more than it needs, in fact. While these extra brain cells provide extra storage for information, they also can decrease efficiency (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). To become more efficient, the brain continues to form new neural connections and becomes faster through pruning. The process of pruning rids the brains of unused neurons and connections, and produces myelin, the fatty tissue that forms around axons and neurons, which helps speed transmissions between different regions of the brain (Blakemore, 2008; Rapoport et al., 1999). This video describes more about “brain remodeling” and how pruning assists in executive function and efficiency in cognitive development: “Shannon Odell: What’s the smartest age? | TED Talk.”

13.3.1.4 Activity: Excessive Pruning and Mental Health

Emerging research suggests that there may be connections to excessive pruning that happens in adolescence and mental health conditions such as schizophrenia. Dr. Steve McCarroll’s team at Harvard are exploring the specialization of cell types related to schizophrenia and pruning. “Steve McCarroll: How data is helping us unravel the mysteries of the brain | TED Talk.”

How is excessive pruning related to cognitive diseases such as schizophrenia as mentioned in the video above? This article explores the C4 protein and environmental factors that can further lead to excessive pruning related to schizophrenia.

What are some of the interdisciplinary approaches that allow this type of innovation to occur?

13.3.2 Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the act of analyzing information presented as facts, evidence, or arguments and being able to make a decision. Critical thinking requires an individual to assess the reliability and validity of information, evaluating the ideas and arguments. Critical thinkers ask key questions, evaluate the evidence, use logical and objective reasoning to problem-solve, synthesize the information so that they can communicate their ideas clearly. Critical thinking skills are applicable in many aspects of an adolescents life, from school, social interactions, and work.

Critical thinking requires the ability to express oneself in spoken and written communication, both of which adolescents have the opportunity to develop and demonstrate in school. It is in adolescence that critical thinking and the cognitive skills associated, such as metacognition, are expected both in school and out. For example, in school adolescents must be able to communicate synthesized information in written assignments. To do this students must be able to evaluate sources and information accessed online. The strategies for thinking about thinking (metacognition) in the evaluation process, will define the quality of the outcome.

Critical thinking is not fully established in adolescence and is something to be practiced. Guided learning provided in school allows students to acquire the experience needed to build their knowledge, including their knowledge of how they learn and their evaluation of their learning. These two defining qualities of metacognition are part of critical thinking as well. In fostering critical thinking, through discussions and written assignments, teachers can foster a student’s ability to understand information in a deeper context by being able to reflect and construct or control their own ideas rather than being controlled by information passively. For students who may face barriers in written or expressive language, accommodations can be made to support the development of critical thinking by utilizing resources the student may already be accessing such as speech or occupational therapy.

13.3.2.1 Relativistic Thinking

Beyond critical thinking, adolescents are also more likely to engage in relativistic thinking, which is the ability to acknowledge that some truths are context dependent. They are more likely to question others’ assertions and less likely to accept information as absolute truth. As they interact more with people outside their family circle, they learn that family rules they believed to be absolute are actually dependent on family and culture. They begin to differentiate between rules crafted from common sense, like don’t touch a hot stove, and those that are based on culturally dependent standards, like a family’s codes of etiquette. This acknowledgement of multiple truths or context dependent norms can lead to the questioning of authority in all domains.

13.3.2.2 Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the Dual-Process Model; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional (Kahneman, 2011). In contrast, Analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational. While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier and more commonly used in everyday life. It is also more commonly used by children and teens than by adults (Klaczynski, 2001). The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

As critical thinking is developing in adolescence, adolescents can utilize strategies for problem solving. Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts that are useful in many cases but may lead to errors as they are often based on biased information, such as a personal experience. Heuristic thinking has broad applications, it is essentially an educated guess about something. We use heuristics all the time, for example, when deciding what groceries to buy from the supermarket, when looking for a library book, when choosing the best route to drive through town to avoid traffic congestion, and so on. Heuristics can be thought of as aids to decision making; they allow us to reach a solution without a lot of cognitive effort or time. They can aid in both our intuitive and analytical thinking (Figure 13.8). The benefit of heuristics in helping us reach decisions fairly easily is also the potential downfall: the solution provided by the use of heuristics is not necessarily the best one.

Figure 13.8. Input into adolescent decision-making process utilizing heuristics thinking strategies or emerging critical thinking skills. These strategies and skills influence the use of intuitive thinking or analytical thinking. Image by Kelly Hoke licensed under CC BY 4.0.

13.3.2.3 Cognitive Empathy

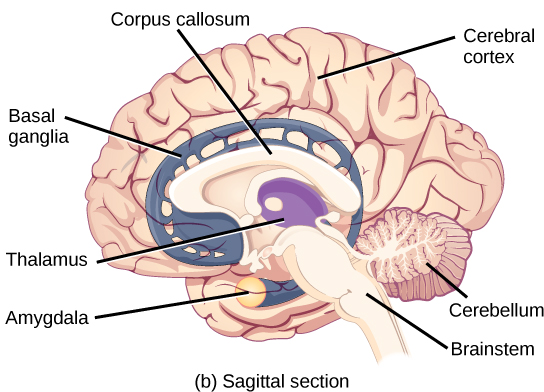

Cognitive empathy relates to the ability to take the perspective of others and feel concern for others (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2005). Cognitive empathy has developmental gains in early childhood and changes across the lifespan, however, studies are mixed if cognitive empathy increases or not during adolescence (Doris et al., 2022; Van der Graaff et al., 2013). Cognitive empathy is an important component of social problem-solving and conflict avoidance. Studies show that modeling perspective taking and that in caregiver-adolescent relationships, validation of a teenagers feelings can support the development of cognitive empathy (Main, Paxton, and Dale, 2016; Main et al., 2019). The limbic system (Figure 13.9) fully matures in early adolescence and is associated with emotional processing. However, for perspective taking to occur there is a reliance on the prefrontal cortex which is associated with critical thinking. The prefrontal cortex however does not mature until adulthood.

Figure 13.9. The Limbic System Adolescence by Martha Lally, Suzanne Valentine-French, and Diana Lang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

13.3.2.4 Impulse Control

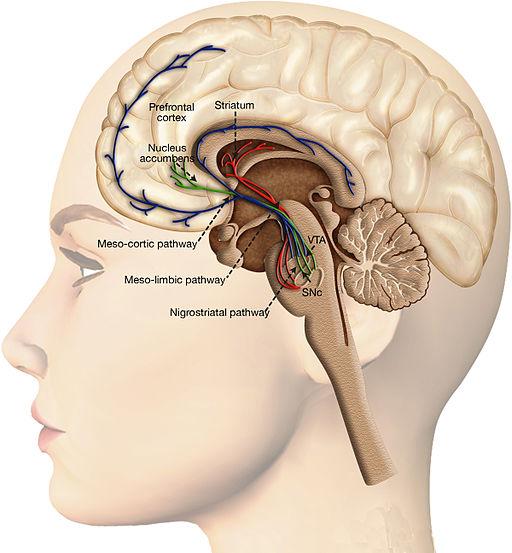

During adolescence, two influential changes occur in the brain leading to changes in cognitive abilities and changes in how individuals begin to view risk and reward. One change is within the prefrontal cortex, which undergoes the most development during this period. The other is changes in dopamine, a chemical in the brain that is a neurotransmitter and produces feelings of pleasure, which can contribute to increases in adolescents’ sensation-seeking and reward motivation (Figure 13.10).

Figure 13.10. Dopaminergic system and reward processing licensed under CC-BY-4.0.

The prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for critical thinking, forming judgments, controlling impulses, and emotional regulation, continues to develop in adolescence (Goldberg, 2001). Even though critical thinking skills are emerging in adolescence, individuals at this age often decide to do activities that produce the most dopamine without full consideration of consequences. The difference in timing of the development of these different regions of the brain contributes to risk-taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are prone to risky behaviors more often than children or adults because they give more weight to rewards. Furthermore, adolescents highly value social connection and their hormones and brains are more attuned to reward those values than to long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Despite the stereotype of adolescents as loose cannons, adolescents are making choices influenced by a very different set of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped-up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Adolescent decisions are not always defined by impulsivity because of lack of brakes, but because of planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in a developmental context. Young people need to somewhat enjoy the thrill of risk-taking to complete the incredibly overwhelming task of growing up. In summary, changes in brain development, information processing, and hormonal changes lead adolescents to:

- Being focused on the present.

- Engaging in risk-taking behaviors.

- Feeling invulnerable.

- Seeking out novel, adventurous, and varied experiences.

13.3.3 Licenses and Attributions for Cognitive Development in Adolescence

“Cognitive Development” and subsections remixed and adapted from:

Lifespan Development by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Human Behavior and the Social Environment I by Susan Tyler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted and from You Don’t Say? Developmental Science Offers Answers to Questions About How Nurture Matters by Emily Spalding is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Adolescent Development by Jennifer Lansford is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

“Shannon Odell: What’s the smartest age? | TED Talk.” License Terms: CC BY — NC — ND 4.0 International.

“Steve McCarroll: How data is helping us unravel the mysteries of the brain | TED Talk”. License Terms: CC BY — NC — ND 4.0 International.

Images

Figure 13.8. Input into adolescent decision-making process utilizing heuristics thinking strategies or emerging critical thinking skills. These strategies and skills influence the use of intuitive thinking or analytical thinking. Image by Kelly Hoke licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 13.9. The Limbic System Adolescence by Martha Lally, Suzanne Valentine-French, and Diana Lang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Figure 13.10. Dopaminergic system and reward processing licensed under CC-BY-4.0.