2.3 Developmental Theories and Perspectives

There are many theories used to describe how children develop over their lifespan. In this textbook, we will focus on a few theories that help us understand growth and provide us with guidance on when to expect changes in learning or skills. We mentioned earlier that theories can become outdated due to cultural shifts and new research findings. Because of this, we do not include many of the developmental theories present in other textbooks. For example, students or instructors who have studied psychology or human development in the past might be surprised that we do not feature Sigmund Freud and his theories. While we recognize that parts of Freud’s work were used by other theorists featured in this textbook, we simply do not find his theories relevant in describing child development in today’s society.

For this section, we will present theories in the order they first appear in the textbook. We will describe each theory and how it applies to a domain of child development. We will also highlight criticisms and biases within the theory that may skew or misinform our understanding of children’s growth. It is important to note that science in Western cultures, such as in the United States, represents a specific set of cultural values. This is often contrasted with a growing ethnically diverse population. Children are often raised in environments that may not fall within the mainstream norms or that combine norms and values from multiple cultures. By recognizing these differences, we can better understand how a child develops within their specific social and cultural environments.

2.3.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Featured in: Chapters 1, 4, 6 and 9

Abraham Maslow was an American psychologist who was interested in many aspects of the human experience. He was motivated to understand human behavior due to his childhood experiences and the horrors witnessed during World War II (Hoffman, 2008). He believed that the field of psychology could remedy social issues by helping people understand each other (Hoffman, 2008). In 1943, Maslow published his famous work “A Theory of Human Motivation” in which he describes the physical and psychological conditions humans need for their well-being.

Figure 2.1 Abraham Maslow. Photo by Corbis licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

In the attempt to understand human behavior, Maslow’s theory categorized people’s actions and needs. He believed that people were motivated to first fulfill their basic needs before moving to “higher” needs (Maslow, 1943). The most basic human needs are defined as physiological needs, those which satisfy our hunger, thirst, sexual reproduction, and important bodily functions. This also includes the need for safety and security which entails healthy attachments to our caregivers, safe and predictable environments, and protection from harm. Maslow believed that when people do not get their basic needs met, they may develop a fixation on these needs or even develop neurosis or psychological issues as a result (Maslow, 1943). This impacts their overall well-being.

The third level in the hierarchy of needs are the social needs which include love, acceptance, and belonging (Cherry, 2022). These needs become the primary focus for individuals once their basic needs are met. Humans seek positive relationships with others and affection through family relationships, romantic relationships, and through community activities such as religious groups or sports (Cherry, 2022). The fourth level of Maslow’s hierarchy includes esteem needs. “All people in our society (with a few pathological exceptions) have a need or desire for a stable, firmly based, (usually) high evaluation of themselves, for self-respect, or self-esteem, and for the esteem of others” (Maslow, 1943). Maslow believed that people strive to be respected and valued by others as well as feel as though they are of value to the world. Together, the social and esteem needs make up the psychological focus of Maslow’s theory (Cherry, 2022).

At the top of Maslow’s hierarchy includes the need to attain self-actualization, or the ability for one to reach their full potential and desires (Maslow, 1943). Once all of the lower needs are satisfied, people can focus on their inner selves. Before Maslow died in 1970, he added an additional level to the hierarchy of needs known as transcendence. He describes transcendence as the highest level of the human experience in which one relates to a higher goal outside of oneself (Messerly, 2017). This amendment is significant in understanding Maslow’s theory because it changes the focus on reaching one’s own potential (personal needs) to serving something that is greater than oneself (world or community needs).

Table 2.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

|

Self-Transcendence |

Focusing one’s energy to a goal or state of consciousness that is higher than the concern for oneself Example: Concern for social justice or global issues |

|

Self-Actualization |

Achieving one’s full abilities or desires Example: A child who loves music becomes a musician |

|

Self-Esteem |

The need to be valued by others and to contribute something to the world Example: Achieving an academic accomplishment |

|

Love, Acceptance, Belonging |

Emotional connection drives human behavior Example: Getting married or being part of a sports team |

|

Safety |

One’s primary need to feel secure and safe in one’s environment and relationships Example: A child forming a positive attachment to a healthy caregiver |

|

Physiological |

One’s primary need to maintain the body’s functions for survival Example: Seeking food and water above all else |

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.1.1 Criticisms of Maslow’s Theory

Despite the importance of Maslow’s theory on human motivation, it has faced many criticisms after publication. The main issue being with the hierarchical nature of the order of needs. Scholars feel that there is insufficient evidence to support that human needs exist in a hierarchy (Celestine, 2017), although modern research confirms that humans across the globe share universal needs (Tay and Diener, 2011). Maslow’s theory is often portrayed as a pyramid, emphasizing the hierarchical nature but it is important to note that Maslow did not create this image of this theory nor did he fully emphasize a strict order to human needs. Maslow recognized that the hierarchy is not rigid and that there are many reasons why people move through the levels in different orders including personal preferences and skills as well as societal standards (Maslow, 1943).

Other issues raised by scholars include failure to account for cultural differences, the impact of gender on the hierarchy of needs, and the impact of an individualist versus collectivist worldview (Celestine, 2017). One of the more notable controversies concerns the origin of Maslow’s theory, which some believe came from the teachings of the Blackfoot tribe. In 1938, Maslow spent several weeks with the Sisika (Blackfoot) people, doing research on the Blackfoot reservation in Canada (Taylor, 2019). He learned about their generosity and how prestige and security were earned in their society (Taylor, 2019).

Many people feel that Maslow appropriated Blackfoot teachings without giving them credit since he published his paper on the hierarchy of needs after his visit (Taylor, 2019). Blackfoot scholars Narcisse Blood and Ryan Heavy Head studied Blackfoot influence on Maslow and summarized their findings in video lectures published in the Blackfoot Digital Library. They found that Maslow was impressed by the levels of cooperation and satisfaction experienced by the community as a whole. He saw that self-actualization (a concept which would later be coined in Maslow’s published work) was a norm for the Blackfoot people which eventually led to a deeper understanding of human motivation (Blood & Heavy Head, 2007).

Given the concern of cultural appropriation and Indigenous erasure in history and modern American culture, it would be important for theorists to acknowledge the origins of theoretical thought and research. Clearly, Maslow learned a lot by immersing himself in Blackfoot culture. While his theory is widely accepted and studied, it is important to acknowledge that it was developed within the context of Western culture, and its applicability to other cultures may be limited. The Blackfoot tribe, for example, has its own unique cultural and spiritual traditions that shape their understanding of human needs and motivations. They do not have a specific model, but their culture values the well-being of the community as a whole, which is just as important as the well-being of the individual. Therefore, their “hierarchy of needs” is more holistic and encompasses the individual’s relationship with the community and the natural world.

2.3.2 Licenses and Attributions for Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

“Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by Terese Jones and Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.3 Social Cognitive Theory (Social Learning Theory)

Featured in Chapters 6, 8

Albert Bandura was a Canadian psychologist who recognized the importance of observation, modeling and imitation in learning. Bandura conducted several experiments to test his theories around observational learning in children (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961; Bandura, 1965). The 1961 lab experiments consisted of preschool aged children observing adult models who were physically and verbally aggressive towards Bobo inflatable dolls. In the 1965 study, children observed adult behavior combined with positive and negative reinforcement. Both sets of studies demonstrated that children mimic observed behaviors, especially when the adult model is rewarded. Imitation was less likely if the adult was reprimanded for their actions.

Figure 2.2 Albert Bandura. Photo by Tobias Deml licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

These studies were key in the development of Bandura’s Social Learning Theory which proposed that children’s behaviors are reinforced by social interactions and context (Bandura, 1977). Bandura’s beliefs aligned with the theories of classical and operant conditioning which state that learning takes place in association with external stimuli and/or through positive and negative reinforcement. Further, Bandura emphasized that both the environment and cognitive factors influence a child’s learning and behavior (Sutton, 2021). Children can learn simply by observing others but “attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation are required in order to benefit from social learning practices” (U.C. Berkeley, 2023).

In 1986, Bandura updated his theory to account for cognitive factors as well as placing emphasis on a child’s sense of self-efficacy, or the belief in their ability to accomplish tasks and goals. The Social Cognitive Theory proposes that learning occurs through the interactions between a person’s environment, personal factors, and behavioral factors (Bandura, 1986).

2.3.3.1 Criticisms of Bandura’s Theory

(list info here)

2.3.4 Licenses and Attributions for Social Cognitive Theory

“Social Cognitive Theory” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.5 Theory of Cognitive Development

Featured in Chapters 5, 7, 10, 13

Jean Piaget (1896–1980) is one of the most influential cognitive theorists (Figure 2.4). Piaget was inspired to explore children’s ability to think and reason by watching his own children’s development. He was one of the first to recognize and map out the ways in which children’s thought differs from that of adults. His interest in this area began when he was asked to test the IQ of children and began to notice that there was a pattern in their wrong answers. He believed that children’s intellectual skills change over time through maturation. Children of differing ages interpret the world differently.

Figure 2.3. Jean Piaget.

Piaget believed our desire to understand the world comes from a need for cognitive equilibrium. This is an agreement or balance between what we sense in the outside world and what we know in our minds. If we experience something that we cannot understand, we try to restore the balance by either changing our thoughts or by altering the experience to fit into what we do understand. Perhaps you meet someone who is very different from anyone you know. How do you make sense of this person? You might use them to establish a new category of people in your mind or you might think about how they are similar to someone else.

A schema or schemes are categories of knowledge. They are like mental boxes of concepts. A child has to learn many concepts. They may have a scheme for “under” and “soft” or “running” and “sour.” All of these are schemas. Our efforts to understand the world around us lead us to develop new schemas and modify old ones.

One way to make sense of new experiences is to focus on how they are similar to what we already know. This is assimilation. So the person we meet who is very different may be understood as being “sort of like my brother” or “his voice sounds a lot like yours.” Or a new food may be assimilated when we determine that it tastes like chicken!

Another way to make sense of the world is to change our minds. We can make a cognitive accommodation to this new experience by adding a new schema. This food is unlike anything I’ve tasted before. I now have a new category of foods that are bitter-sweet in flavor, for instance. This is accommodation. Do you accommodate or assimilate more frequently? Children accommodate more frequently as they build new schemas. Adults tend to look for similarities in their experiences and assimilate. They may be less inclined to think “outside the box.”

Piaget suggested different ways of understanding that are associated with maturation. He divided this into four stages (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development

|

Name of Stage |

Description of Stage |

|

Sensorimotor Stage |

Piaget believed that at the outset of life children are working to develop their sensory systems and motor skills. They exercise their senses through use and practice, and many parents can remember times when their children touched everything or put everything in their mouths and smelled everything. Because the only way children have of taking in information is through their senses, and the only way to move and take care of themselves is through their motor skills, it’s quite logical that the first stage of life would include a great effort to refine these skills. |

|

Preoperational Stage |

Children now have fairly well-developed sensory systems but have not yet developed logic to make sense with which to make sense out of all they can perceive. For instance, they use their ability to generalize in an illogical way, perhaps believing that, because they have a cat, all fur-bearing fur bearing animals are cats, and noticing parts of an object, but not relating the whole object. Children in this stage often see things as static and unchanging. They also lack the skill of reversibility, not being able to tell that water poured from a tall thin glass is still the same amount of water when it is poured into a short, wide glass. Perhaps because of their limited ability to understand all that they perceive, children often ask “why,” sometimes driving their parents to distraction. And, since we don’t allow children to experience adult life and adult concerns, they often act out fantasy games and make-believe during this stage in an effort to experience and understand the world. |

|

Concrete Operational |

Children in the concrete operational stage, ages 7–11, develop the ability to think logically about the physical world. Middle childhood is a time of understanding concepts such as size, distance, constancy of matter, and cause-and-effect relationships. A child knows that a scrambled egg is still an egg and that 8 fl oz of water is still 8 fl oz no matter what shape of glass contains it. |

|

Formal Operational |

During the formal operational stage children, at about age 12, acquire the ability to think logically about concrete and abstract events. The teenager who has reached this stage is able to consider possibilities and contemplate ideas about situations that have never been directly encountered. More abstract understanding of religious ideas or morals or ethics and abstract principles such as freedom and dignity can be considered. |

Table 2.2 by “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.5.1 Criticisms of Piaget’s Theory

Although Piaget’s theory has made significant contributions to the science of child development, Piaget has been criticized for overemphasizing the role that physical maturation plays in cognitive development and in underestimating the role that culture and interaction (or experience) play in cognitive development. Looking across cultures reveals considerable variation in what children are able to do at various ages. Piaget may have underestimated what children are capable of given the right circumstances.

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that cognitive development is complete by the age of 12, however most recent research demonstrates that this developmental period of adolescence is one of important cognitive increases. Another main criticism of Piaget is his methodological approach, especially in using his own children and cultural bias.

2.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Theory of Cognitive Development

“Theory of Cognitive Development” from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.7 Psychosocial Theory

Featured in Chapters 6 and 8

Erik Erikson (1902–1994) suggested that our relationships and society’s expectations motivate much of our behavior in his theory of psychosocial development (Figure 2.6). Erikson was a student of Freud but emphasized the importance of the ego, or conscious thought, in determining our actions. In other words, he believed that we are not driven by unconscious urges. We know what motivates us and consciously think about how to achieve our goals. He is considered the father of developmental psychology because his model gives us a guideline for the entire life span and suggests certain primary psychological and social concerns throughout life.

Figure 2.4. Erik Erikson.

Erikson expanded on Freud’s theory by emphasizing the importance of culture in parenting practices and motivations and adding three stages of adult development (Erikson, 1950; 1968). He believed that we are aware of what motivates us throughout life and that the ego has greater importance in guiding our actions than the id. We make conscious choices in life, and these choices focus on meeting certain social and cultural needs rather than purely biological ones. Humans are motivated, for instance, by the need to feel that the world is a trustworthy place, that we are capable individuals, that we can contribute to society, and that we have lived a meaningful life. These are all psychosocial problems.

Erikson divided the lifespan into eight stages (table 2.3). In each stage, we have a major psychosocial task to accomplish or a crisis to overcome. Erikson believed that our personality continues to take shape throughout our lifespan as we face these challenges in living.

Table 2.3. Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory

|

Name of Stage |

Description of Stage |

|

Trust vs. mistrust (0–1) |

The infant must have basic needs met consistently to feel that the world is a trustworthy place. |

|

Autonomy vs. shame and doubt (1–2) |

Mobile toddlers have newfound freedom they like to exercise, and by being allowed to do so, they learn some basic independence. |

|

Initiative vs. Guilt (3–5) |

Preschoolers like to initiate activities and emphasize doing things “all by myself.” |

|

Industry vs. inferiority (6–11) |

School-aged children focus on accomplishments and begin comparing themselves with their classmates. |

|

Identity vs. role confusion (adolescence) |

Teenagers try to gain a sense of identity as they experiment with various roles, beliefs, and ideas. |

|

Intimacy vs. Isolation (young adulthood) |

In our 20s and 30s, we make some of our first long-term commitments in intimate relationships. |

|

Generativity vs. stagnation (middle adulthood) |

In the 40s through the early 60s, we focus on being productive at work and home and are motivated by wanting to feel that we’ve contributed to society. |

|

Integrity vs. Despair (late adulthood) |

We look back on our lives and hope to like what we see—that we have lived well and have a sense of integrity because we lived according to our beliefs. |

Table 2.3 by “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

These eight stages form a foundation for discussions on emotional and social development during a lifespan. However, remember that these stages or crises can occur more than once. For instance, a person may struggle with a lack of trust beyond infancy under certain circumstances. Erikson’s theory has been criticized for focusing so heavily on stages and assuming that the completion of one stage is a prerequisite for the next crisis of development. His theory also focuses on the social expectations in certain cultures but not in all. For instance, the idea that adolescence is a time of searching for identity might translate well in the middle-class culture of the United States but not as well in cultures where the transition into adulthood coincides with puberty through rites of passage and where adult roles offer fewer choices.

2.3.8 Licenses and Attributions for Psychosocial Theory

“Psychosocial Theory” from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.9 Sociocultural Theory

Features in Chapters 5, 7, 10, 13

Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a Russian psychologist who wrote in the early 1900s but whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s (Figure 2.8). Vygotsky differed from Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development. His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning.

Figure 2.5. Lev Vygotsky.

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you all through the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do—you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen demonstrated throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern-day educators.

|

Main Points to Note About Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory |

|

Vygotsky concentrated on the child’s interactions with peers and adults. He believed that the child was an apprentice, learning through sensitive social interactions with more skilled peers and adults. |

Vygotsky concentrated more on the child’s immediate social and cultural environment and his or her interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning through a social environment of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities.

A criticism of Vygotsky’s work is that of cultural bias, that there is an assumption that the theory is relevant regardless of culture. While Vygotsky emphasized social and cultural influences, he neglected biological factors.

2.3.10 Licenses and Attributions for Sociocultural Theory

“Sociocultural Theory” from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

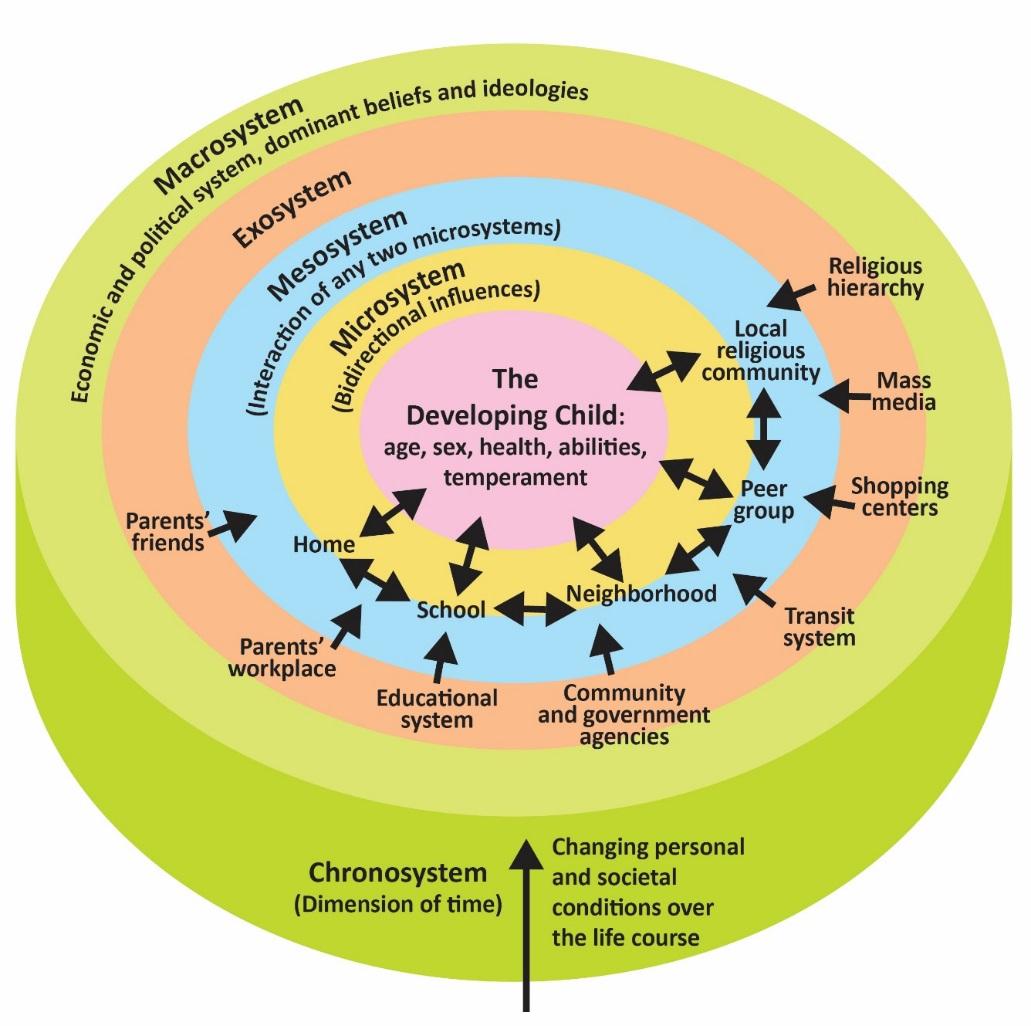

2.3.11 Ecological Systems Model

Featured in Chapters 5, 10, 13

Like Vygotsky, Bronfenbrenner looked at the social influences on learning and development. Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005) offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development (Figure 2.9). Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

Figure 2.6. Urie Bronfenbrenner.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model explains the direct and indirect influences on an individual’s development (Figure 2.10 and Figure 2.11).

Table 2.4 Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model

|

Name of System |

Description of System |

|

Microsystems |

Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them needs to be considered. For example, to appreciate what is going on with a student in math, the relationship between the student and teacher should be known. |

|

Mesosystems |

Mesosystems are interactions between those surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example, will indirectly affect the child. |

|

Exosystem |

Larger institutions such as the mass media or the healthcare system are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families, peers, and schools that operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions. |

|

Macrosystems |

We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual. |

|

Chronosystem |

All of this happens in a historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies of educational institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time. |

Table 2.4 by “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

For example, in order to understand a student in math, we can’t simply look at that individual and what challenges they face directly with the subject. We have to look at the interactions that occur between teacher and child. Perhaps the teacher needs to make modifications as well. The teacher may be responding to regulations made by the school, such as new expectations for students in math or constraints on time that interfere with the teacher’s ability to instruct. These new demands may be a response to national efforts to promote math and science deemed important by political leaders in response to relations with other countries at a particular time in history.

Figure 2.7. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model challenges us to go beyond the individual if we want to understand human development and promote improvements.

2.3.12 Licenses and Attributions for Ecological Systems Model

“Ecological Systems Model” from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

2.3.13 Licenses and Attributions for Developmental Theories and Perspectives

“Theory of Cognitive Development” is adapted from Lecture Transcript: Developmental Theories by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0 (modified by Jennifer Paris) and Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Psychosocial Theory” is adapted from Psychosocial Theory by Lumen Learning which is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Sociocultural Theory” is adapted from Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ecological Systems Model” is adapted from Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.1 “Abraham Maslow” by Corbis is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.2 “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.3 “Albert Bandura” by Tobias Deml is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.4 “Jean Piaget” by Unidentified (Ensian published by University of Michigan), Wikipedia is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.5. “Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development” by Terese Jones, Christina Belli, and Esmeralda Janeth Julyan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.6. “Erik Erikson” by Unknown Author, Wikimedia is in the Public Domain.

Figure 2.7 ”Erik Erikson’s Psychosocial Theory” by Terese Jones, Christina Belli, and Esmeralda Janeth Julyan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.8 “Lev Vygotsky” by The Vigotsky Project is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 2.9 “Urie Bronfenbrenner” by Marco Vicente González is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.10. “Urie Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Model” by Terese Jones, Christina Belli, and Esmeralda Janeth Julyan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.11 “Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory” by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0.