6.6 Emotional Development

At birth, infants exhibit two emotional responses: attraction and withdrawal. They show attraction to pleasant situations that bring comfort, stimulation, and pleasure, and they withdraw from unpleasant stimulation such as bitter flavors or physical discomfort (Figure 6.7). At around 2 months, infants exhibit social engagement in the form of social smiling as they respond with smiles to those who engage their positive attention (Lavelli & Fogel, 2005).

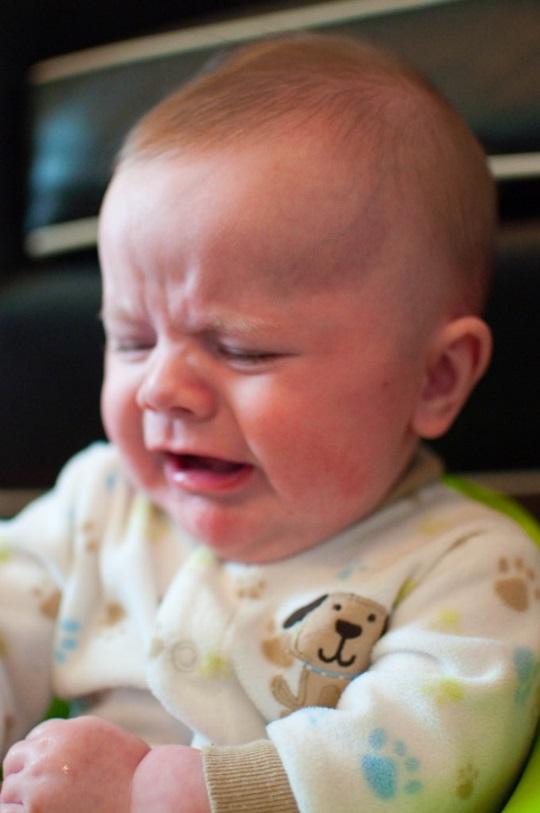

Social smiling becomes more stable and organized as infants learn to use their smiles to engage their parents in interactions. Pleasure is expressed as laughter at 3–5 months of age, and displeasure becomes more specific as fear, sadness, or anger between ages 6–8 months. Anger is often the reaction to being prevented from obtaining a goal, such as a toy being removed (Braungart-Rieker et al., 2010). In contrast, sadness is typically the response when infants are deprived of a caregiver (Papousek, 2007). Fear is often associated with the presence of a stranger, known as stranger wariness, or the departure of significant others, known as separation anxiety. Both appear sometime between 6–15 months after object permanence has been acquired. Further, there is some indication that infants may experience jealousy as young as 6 months of age (Hart & Carrington, 2002).

Figure 6.6. An infant making an angry facial expression.

Emotions are often divided into two general categories: basic emotions (primary emotions), such as interest, happiness, anger, fear, surprise, sadness, and disgust, which appear first, and self-conscious emotions (secondary emotions), such as envy, pride, shame, guilt, doubt, and embarrassment (Figure 6.8). Unlike primary emotions, secondary emotions appear as children start to develop a self-concept, and require social instruction on when to feel such emotions. The situations in which children learn self-conscious emotions vary from culture to culture. Individualistic cultures teach us to feel pride in personal accomplishments, while in more collective cultures children are taught to not call attention to themselves, unless they wish to feel embarrassed for doing so (Akimoto & Sanbinmatsu, 1999).

Figure 6.7. An infant making a sad facial expression.

Facial expressions of emotion are important regulators of social interaction. In the developmental literature, this concept has been investigated under the concept of social referencing; that is, the process whereby infants seek out information via facial cues from others to clarify a situation and then use that information to act (Klinnert et al., 1983).

To date, the strongest demonstration of social referencing comes from work on the visual cliff. In the first study to investigate this concept, Campos and colleagues (Sorce et al., 1985) placed mothers on the far end of the “cliff” from the infant. Mothers first smiled at the infants and placed a toy on top of the safety glass to attract them; infants invariably began crawling to their mothers. When the infants were in the center of the table, however, the mother then posed an expression of fear, sadness, anger, interest, or joy. The results were clearly different for the different faces; no infant crossed the table when the mother showed fear; only six percent did when the mother posed anger, 33 percent crossed when the mother posed sadness, and approximately 75 percent of the infants crossed when the mother posed joy or interest.

Other studies provide similar support for facial expressions as regulators of social interaction. Researchers posed facial expressions of neutral, anger, or disgust toward babies as they moved toward an object and measured the amount of inhibition the babies showed in touching the object (Bradshaw, 1986). The results for 10– and 15-month-olds were the same: Anger produced the greatest inhibition, followed by disgust, with neutral the least. This study was later replicated using joy and disgust expressions, altering the method so that the infants were not allowed to touch the toy (compared with a distractor object) until 1 hour after exposure to the expression (Hertenstein & Campos, 2004). At 14 months of age, significantly more infants touched the toy when they saw joyful expressions, but fewer touched the toy when the infants saw disgust.

A final emotional change is in self-regulation. Emotional self-regulation refers to strategies we use to control our emotional states so that we can attain goals (Thompson & Goodvin, 2007). This requires effortful control of emotions and initially requires assistance from caregivers (Rothbart et al., 2006). Young infants have very limited capacity to adjust their emotional states and depend on their caregivers to help soothe themselves. Caregivers can offer distractions to redirect the infant’s attention and comfort to reduce emotional distress. As areas of the infant’s prefrontal cortex continue to develop, infants can tolerate more stimulation.

By 4–6 months, babies can begin to shift their attention away from upsetting stimuli (Rothbart et al., 2006). Older infants and toddlers can more effectively communicate their need for help and can crawl or walk toward or away from various situations (Cole et al., 2010). This aids in their ability to self-regulate. Temperament also plays a role in children’s ability to control their emotional states, and individual differences have been noted in the emotional self-regulation of infants and toddlers (Rothbart & Bates, 2006).

6.6.1 Licenses and Attributions for Emotional Development

“Emotional Expression” from Lifespan Development – A Psychological Perspective by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under CC BY 4.0 with minor edits.

Figure 6.6. “Person Carrying Baby” by Brytny.com on Unsplash.

Figure 6.7. “Cry Baby” by acheron0 is licensed under CC BY 2.0