2.4 Social, Environmental, and Attachment Theories

The theories presented in this section are similar to stage theories because they help us explain and understand behavior. Yet, these theories do not follow a specific progression and instead acknowledge that behavior and skills are influenced by many factors, such as social context, environmental influences, and caregiver interactions. Therefore, changes or leaps in development can happen at any time, for many reasons.

We will provide some background on each theory and include important criticisms and biases within the theory that may misinform our understanding of child development. It is important to note that science in Western cultures, such as in the United States, represents a specific set of cultural values. This is often contrasted with a growing, ethnically diverse population. Children are often raised in environments that may not follow mainstream norms or that combine norms and values from multiple cultures. By recognizing these differences, we can better understand how children develop within their specific social and cultural environments.

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Featured in: Chapter 1, Chapter 4, Chapter 6, and Chapter 9.

Abraham Maslow (1908-1970) was an American psychologist who was interested in many aspects of the human experience. He was motivated to understand human behavior due to his childhood experiences and the horrors he witnessed in the United States during World War II (Hoffman, 2008). He believed that the field of psychology could remedy social issues by helping people understand each other (Hoffman, 2008). In 1943, Maslow published his famous work A Theory of Human Motivation in which he describes the physical and psychological conditions humans need for their well-being.

In his attempt to understand human behavior, Maslow’s theory categorized people’s actions and needs into a hierarchy of needs, which we previously introduced in Chapter 1. He believed that people were motivated to first fulfill their basic needs before moving to “higher” needs (Maslow, 1943). The most basic human needs are defined as physiological needs, those which satisfy our hunger, thirst, sexual reproduction, and important bodily functions. This also includes the need for safety and security, which entails healthy attachments to our caregivers, safe and predictable environments, and protection from harm. Maslow believed that when people’s basic needs are not met, they may develop a fixation on those needs and even develop neurosis or psychological issues as a result (Maslow, 1943). This impacts their overall well-being.

The third level in the hierarchy of needs is the social needs, which include love, acceptance, and belonging (Cherry, 2022). These needs become the primary focus for individuals once their basic needs are met. Humans seek positive relationships with others and affection through family relationships, romantic relationships, and community activities, such as religious groups or sports (Cherry, 2022). The fourth level of Maslow’s hierarchy includes esteem needs. “All people in our society (with a few pathological exceptions) have a need or desire for a stable, firmly based, (usually) high evaluation of themselves, for self-respect, or self-esteem, and for the esteem of others” (Maslow, 1943). Maslow believed that people strive to be respected and valued by others, as well as to feel as though they are of value to the world. Together, the social and esteem needs make up the psychological focus of Maslow’s theory (Cherry, 2022).

At the top of Maslow’s hierarchy is the need to attain self-actualization, or a person’s ability to reach their full potential and desires (Maslow, 1943). Once all of the lower needs are satisfied, people can focus on their inner selves. Before Maslow died in 1970, he added an additional level known as transcendence to the hierarchy of needs (Figure 2.4). He describes transcendence as the highest level of the human experience in which one relates to a higher goal outside of oneself (Messerly, 2017). This amendment is significant in understanding Maslow’s theory because it changes the focus from fulfilling one’s own potential (personal needs) to serving something that is greater than oneself (world or community needs).

| Need | Definition |

|---|---|

| Self-transcendence | One’s dedication of energy to reaching a goal or a state of consciousness that is higher than one’s concern for oneself

Example: Concern for social justice or global issues |

| Self-actualization | Achieving one’s full abilities or desires

Example: Becoming a musician because of a love for music |

| Self-esteem | One’s need to be valued by others and to contribute something to the world

Example: Achieving an academic accomplishment |

| Love, acceptance, belonging | One’s need for emotional connection, which drives human behavior

Example: Getting married or being part of a sports team |

| Safety | One’s primary need to feel secure and safe in one’s environment and relationships

Example: Forming a positive attachment to a healthy caregiver |

| Physiological | One’s primary need to maintain the body’s functions for survival

Example: Seeking food and water above all else |

Criticisms of Maslow’s Theory

Despite the importance of Maslow’s theory on human motivation, it has faced many criticisms since its publication. The main issue raised by critics concerns the hierarchical nature of the order of needs. Scholars feel that there is insufficient evidence to support the idea that human needs exist in a hierarchy (Celestine, 2017), although modern research confirms that humans across the globe share universal needs (Tay and Diener, 2011). Maslow’s theory is often portrayed as a pyramid, emphasizing the hierarchical nature, but it is important to note that Maslow did not create this image of this theory, nor did he fully emphasize a strict order to human needs. Maslow recognized that the hierarchy is not rigid and that there are many reasons why people move through the levels in different orders, including personal preferences and skills, as well as societal standards (Maslow, 1943).

Other issues raised by scholars include the failure of the hierarchy to account for cultural differences, the impact of gender on the hierarchy of needs, and the impact of an individualist versus collectivist worldview (Celestine, 2017). One of the more notable controversies concerns the origin of Maslow’s theory. In 1938, Maslow spent several weeks with the Sisika (Blackfoot) people, doing research on the Blackfoot reservation in Canada (Taylor, 2019). He learned about their generosity and how prestige and security were earned in their society (Taylor, 2019). Many people feel that Maslow appropriated Blackfoot teachings without giving them credit, since he published his paper on the hierarchy of needs after his visit (Taylor, 2019). Blackfoot scholars Narcisse Blood and Ryan Heavy Head studied Blackfoot influence on Maslow and summarized their findings in video lectures published in the Blackfoot Digital Library. They found that Maslow was impressed by the levels of cooperation and satisfaction experienced by the community as a whole. He saw that self-actualization (a concept which would later be coined in Maslow’s published work) was a norm for the Blackfoot people, which eventually led to a deeper understanding of human motivation (Blood & Heavy Head, 2007). Given the concern of cultural appropriation and Indigenous erasure in history and modern American culture, it is important for theorists to acknowledge the origins of theoretical thought and research. Clearly, Maslow learned a lot by immersing himself in Blackfoot culture.

While Maslow’s theory is widely accepted and studied, it is important to acknowledge that it was developed within the context of Western culture, and its applicability to other cultures may be limited. The Blackfoot tribe, for example, has its own unique cultural and spiritual traditions that shape its understanding of human needs and motivations. They do not have a specific model, but their culture values the well-being of the community as a whole, which is just as important as the well-being of the individual. Therefore, their “hierarchy of needs” is more holistic and encompasses the individual’s relationship with the community and the natural world.

Social Cognitive Theory (Social Learning Theory)

Featured in Chapter 6 and Chapter 8.

Albert Bandura (1925-2021) was a Canadian psychologist who recognized the importance of observation, modeling, and imitation in learning. Bandura conducted several experiments to test his theories around observational learning in children (Bandura, Ross, & Ross, 1961; Bandura, 1965). His 1961 lab experiments consisted of preschool aged children observing adult models who were physically and verbally aggressive toward Bobo inflatable dolls. In his 1965 study, children observed adult behavior combined with positive and negative reinforcement. Both sets of studies demonstrated that children mimic observed behaviors, especially when the adult model is rewarded. Imitation was less likely if the adult was reprimanded for their actions.

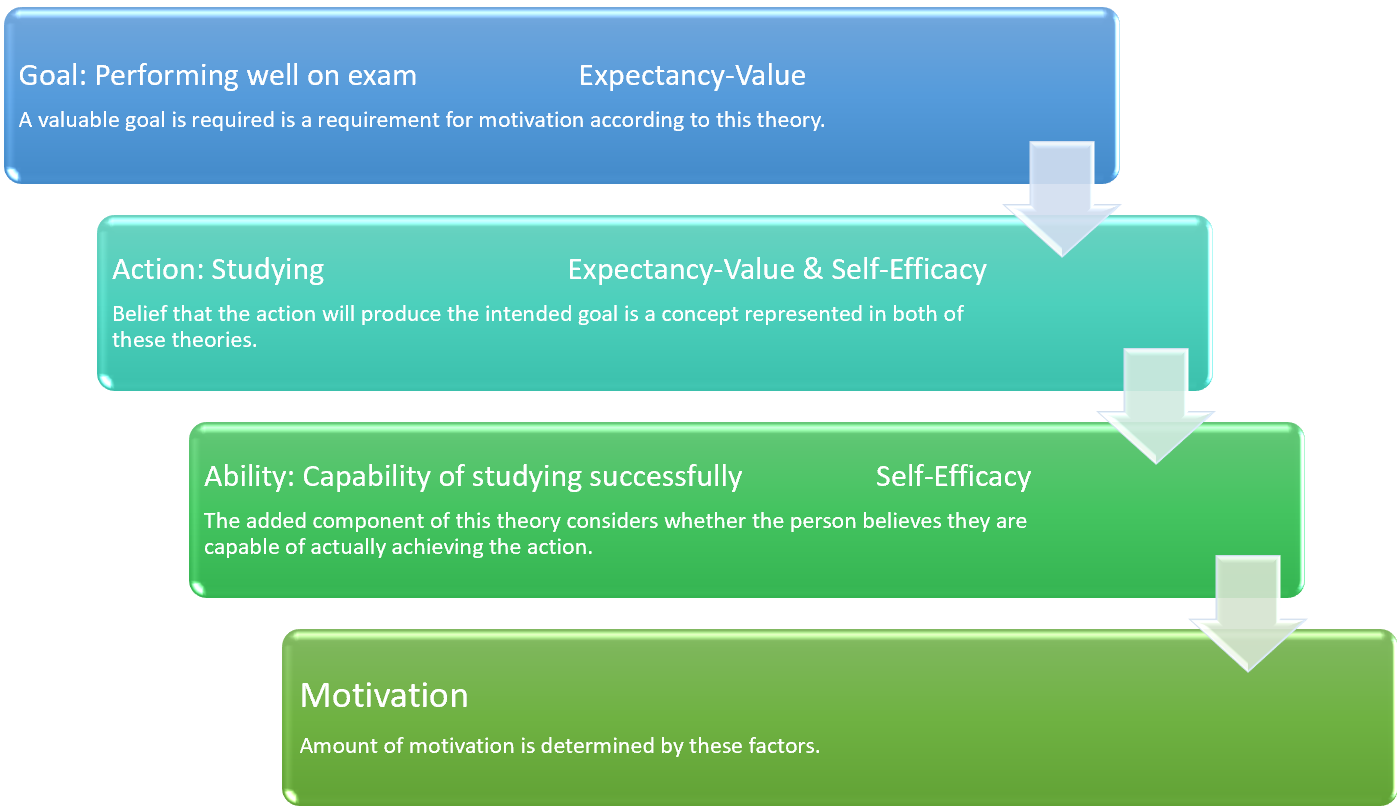

These studies were key in the development of Bandura’s social learning theory, illustrated in figure 2.5, which proposes that children’s behaviors are reinforced by social interactions and context (Bandura, 1977). Bandura’s beliefs aligned with the theories of classical and operant conditioning, which state that learning takes place in association with external stimuli and/or through positive and negative reinforcement. Further, Bandura emphasized that both the environment and cognitive factors influence a child’s learning and behavior (Sutton, 2021). Children can learn simply by observing others, but “attention, retention, reproduction, and motivation are required in order to benefit from social learning practices” (U.C. Berkeley, 2023).

In 1986, Bandura updated his theory to account for cognitive factors, as well as placing emphasis on a child’s sense of self-efficacy, or the belief in their ability to accomplish tasks and goals. Social cognitive theory proposes that learning occurs through the interactions between a person’s environment, personal factors, and behavioral factors (Bandura, 1986).

Criticisms of Bandura’s Theory

Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory has been helpful in understanding and sometimes predicting people’s behavior, but it is not without some criticism. The Bobo Doll studies shed light on how a child might learn about aggression, which has been instrumental when researching the effects of media, such as violence on television or in video games. Unfortunately, the studies themselves are considered unethical due to the fact that they exposed young children to, and taught them to exhibit, aggression. Another criticism includes the lack of attention to biological factors, which may downplay the importance of temperament and personality in how children learn. There are also cognitive differences in how children learn, which can influence whether or not children will mimic the behaviors they are exposed to.

Sociocultural Theory

Featured in Chapter 5, Chapter 7, Chapter 10, and Chapter 13.

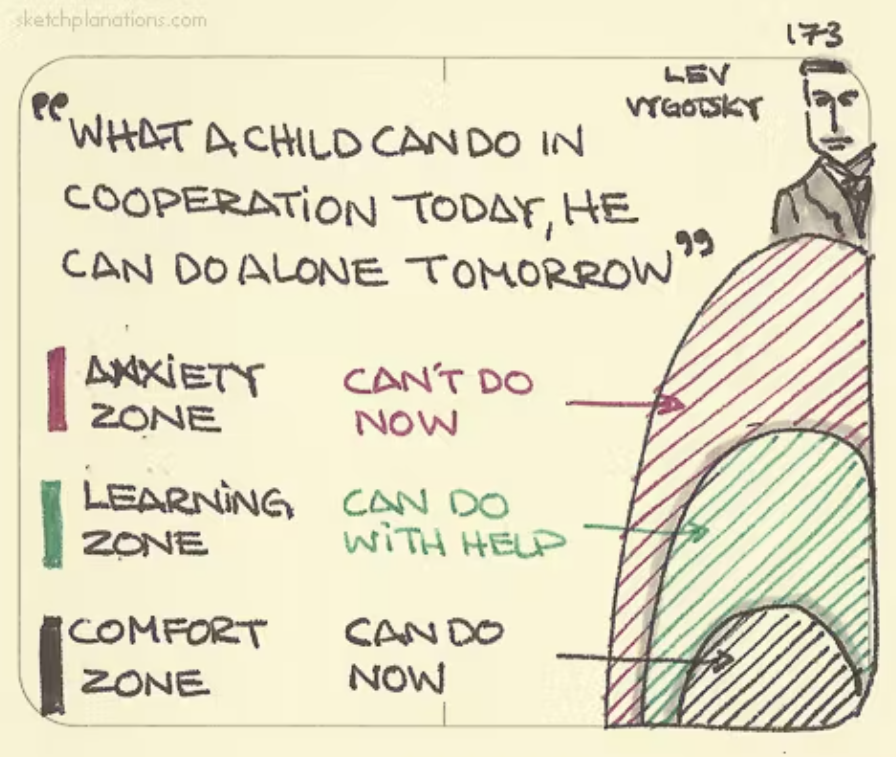

Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) was a Russian psychologist whose work was discovered in the United States in the 1960s but became more widely known in the 1980s (figure 2.6). Vygotsky differed from Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. His sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development. His belief was that development occurred first through children’s immediate social interactions, and then moved to the individual level as they began to internalize their learning.

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are, you spoke to them, describing what you were doing as you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you throughout the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do, you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding and can be seen in cultures throughout the world. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance. You can see how Vygotsky would be very popular with modern-day educators.

Vygotsky concentrated on the child’s interactions with peers and adults. He believed that the child was an apprentice, learning through sensitive social interactions with more skilled peers and adults.

Vygotsky concentrated more on children’s immediate social and cultural environment and their interactions with adults and peers. While Piaget saw the child as actively discovering the world through individual interactions with it, Vygotsky saw the child as more of an apprentice, learning in a social environment under the guidance of others who had more experience and were sensitive to the child’s needs and abilities.

Criticisms of Vygotsky’s Theory

Vygotsky’s social cognitive theory has been instrumental in understanding how children’s learning is impacted by their social environment. One of the criticisms of Vygotsky’s work is the assumption that the theory is relevant regardless of culture. For example, is learning similar when looking at individualistic cultures versus collectivist ones? Similarly, social cognitive theory does not take into account biological factors, such as the child’s unique skills and functioning. Things like temperament or personality can have a profound impact on how a child learns.

Ecological Systems Model

Featured in Chapter 5, Chapter 7, Chapter 10, and Chapter 13.

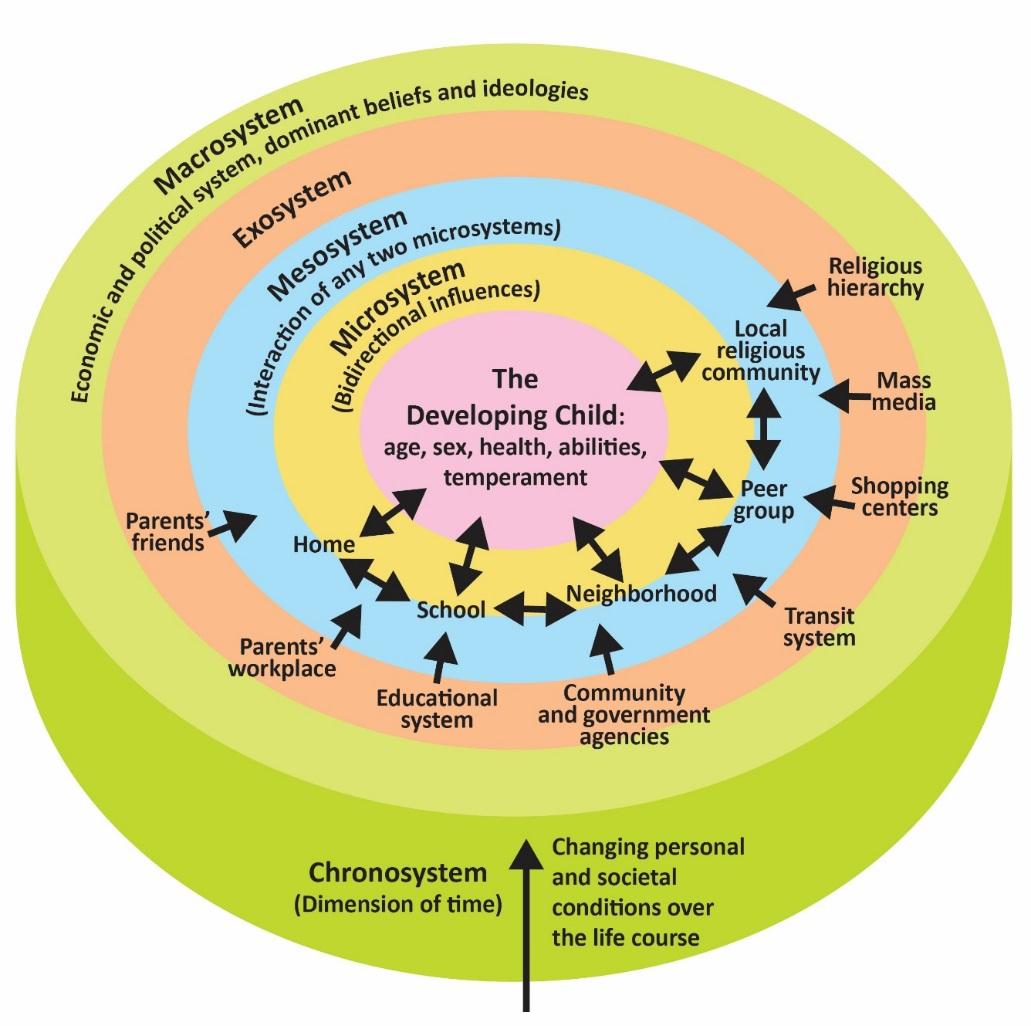

Like Vygotsky, Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917–2005) examined social influences on learning and development. Bronfenbrenner offers us one of the most comprehensive theories of human development (figure 2.7). He studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and learning theorists and believed that all of those theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context. What is being taught and how society interprets situations depends on who is involved in the life of a child and on when and where a child lives.

| Name of System | Description of System |

|---|---|

| Microsystems | Microsystems impact a child directly. These are the people with whom the child interacts, such as parents, peers, and teachers. The relationship between individuals and those around them needs to be considered. For example, to understand a student’s progress in math, it’s essential to know the relationship between the student and teacher. |

| Mesosystems | Mesosystems are interactions between the people and institutions surrounding the individual. The relationship between parents and schools, for example, will indirectly affect the child. |

| Exosystem | Larger institutions, such as the mass media or the health-care system, are referred to as the exosystem. These have an impact on families, peers, and schools that operate under the policies and regulations found in these institutions. |

| Macrosystems | We find cultural values and beliefs at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual. |

| Chronosystem | All of this happens in a historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do the policies of educational institutions and governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time. |

For example, to understand a student in a math class, we can’t simply look at that individual and what challenges they face directly with the subject. We also have to look at the interactions that occur between teacher and child. Furthermore, we need to account for any modifications the teacher needs to make. The teacher may be responding to regulations made by the school, such as new student benchmarks or time constraints that interfere with the teacher’s ability to instruct. These new demands may be in response to national efforts to promote math and science, which may in turn have been prompted by international relations at a particular time in history.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems model challenges us to go beyond the individual if we want to understand human development and promote improvements.

Criticisms of Bronfenbrenner’s Theory

Bronfenbrenner’s work provides a holistic view of how people learn and adapt, which allows the theory to be applied in many situations and cultural contexts. The biggest criticism of his theory is that it cannot be fully measured or empirically tested. While we can apply the theory in practice, we may not be able to attribute specific outcomes to the theory itself. Despite this, Bronfenbrenner’s work has been valuable in analyzing children’s behavior through a wider and more comprehensive lens.

Licenses and Attributions for Social, Environmental, and Attachment Theories

“Social, Environmental, and Attachment Theories” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Criticisms of Maslow’s Theory” by Christina Belli and Terese Jones licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sociocultural Theory” by Christina Belli is adapted from is adapted from Exploring Cognition by Lumen Learning which is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Children’s Development by Ana R. Leon which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Ecological Systems Model” is adapted by Christina Belli, from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.4. Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.5. Expectancy-Value & Self-Efficacy Factors of Motivation by U3142852 in Wikimedia is licensed CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 2.6. Zone of Proximal Development by SketchPlantations is licensed CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 2.7. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory by Ian Joslin is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.8. Table is adapted from “Child Growth and Development” by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

the study of how humans change and grow over their lifespan.