3.6 Pregnancy and Social Context

Pregnancy is a major life event that involves dramatic changes to a pregnant person’s body and brain. These changes are well documented but researchers often ignore the role that pregnancy plays in a mother’s social life and cultural world. While pregnancy is often celebrated and even revered across the globe, it is experienced differently depending on the social factors surrounding the pregnant mother. Factors such as age, social class, race/ethnicity, and gender identity all intersect with the pregnancy experience. One phenomenon that is universally shared amongst pregnant women is navigating the social expectations and cultural influences during the 40 weeks of gestation. These pressures have a direct impact on the mother’s physical and mental well-being, as well as on the developing child. In this section, we will take a closer look into social and cultural factors that influence pregnancy experiences and outcomes.

Systemic Issues and Social Inequalities

In Chapter 1, we learned that our society has been structured in a way that creates social inequalities. These are caused by biases and practices embedded within systems such as the school system, housing, health care, and government. The pervasive presence of bias creates unnecessary barriers for people and can impact many facets of one’s life. Social and group identities play a crucial role in the opportunities people are afforded and the barriers they face. Pregnant people are a vulnerable group that are uniquely impacted by social issues. This is further compacted by facets of their identity such as race, social class, and gender.

Gender is a social construct based on biological sex. Our society has different roles and norms assigned to people depending on whether they are born a male or female. This type of binary system does not allow for much diversity or acceptance for people, especially those born as intersex or whose gender identity differs from the standard male or female. Cisgender means that a person’s gender identity coincides with the sex they were assigned at birth. Transgender means that a person’s gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. In pregnancy, transgender men face unique challenges navigating the health-care system and stigmas related to their identity. We will discuss this later in this section.

Racism is a system of disadvantage based on race or perceived race. Pregnant women from racial minority groups such as Native American/Indigenous, African American/Black, and Latinx/Hispanic experience race differently than White women due to the power structures that advantage White people over others. Women of color experience maternal mortality, complications during pregnancy and labor, and adverse impacts to their developing fetus at much higher rates than their White counterparts (Kozhimannil et al., 2011).

In a report published by the CDC, it is noted that there are multiple factors that contribute to racial disparities in pregnancy-related mortality (Peterson et al., 2019). Implicit bias, or the unconscious beliefs and attitudes that influence our judgments and actions, exists in the health care system. This bias, along with structural racism, impacts the way providers interact with their patients, the level of care provided to an expecting mother, and treatment decisions. Mistreatment in medical settings is experienced more frequently by women of color, resulting in unnecessary medical interventions and impacting the safety and quality of the pregnancy experience (Vedam et al., 2019).

Classism is a system of advantage based on socioeconomic status. Pregnant women from a higher social class have access to quality health care, nutrition, and resources before, during, and after their pregnancy. Pregnant women from lower socioeconomic groups often have limited or no access to preventative or prenatal care or nutritious foods to support their changing bodies. They also often live in neighborhoods that contain higher levels of environmental toxins, many of which are known to cause disruption or defects in fetal development.

It is important to note that gender, race, and class are not the only social categories that impact expecting mothers. Prejudice and discrimination based on traits such as ability (ableism), sex (sexism), language, and citizenship status, also occurs. A pregnant person may have several intersecting identity labels that can result in compounded oppression and increased risks during pregnancy and throughout parenthood.

Case Study: Consuelo and Gabriela

How do social inequalities impact the birth experience and access to services?

Consuelo was born and raised in Mexico and moved to California with her husband and two children. They had a relatively easy transition and settled among family and friends in California. After a few months, Consuelo found out she was pregnant with Gabriela.

At this point, Consuelo had learned some important English phrases, but she had trouble communicating with medical staff during her prenatal visits. She requested an interpreter several times, but sometimes there wasn’t one available. Consuelo often felt like her concerns were not treated with urgency or care.

As she approached the final weeks of her pregnancy, Consuelo was overcome with chest pain and dizziness. This often resulted in vision disturbances or nausea. She communicated her concerns with the translator, who then reported to the doctor. Consuelo was given an antacid and told to rest. The issues persisted, and again Consuelo relayed her concerns to medical staff, who advised her to rest.

Consuelo’s husband rushed her to the emergency room a few days later due to severe bleeding and abdominal pain. Upon examination, medical staff realized that Consuelo had preeclampsia, a serious medical complication, which can slow down the passage of oxygen and nutrients from the mother to the baby. Since the preeclampsia was not diagnosed properly during prenatal visits, Consuelo suffered an abruption of the placenta, which is when the placenta separates from the uterine wall. Both she and the baby were at high risk for complications and even death.

Medical staff performed an emergency C-section as well as treated Consuelo, who needed a blood transfusion. Gabriela suffered some stress and was weak as a result. Consuelo’s recovery was difficult, but she was fortunate to have some family support during her aftercare. She was hesitant to go back to the hospital for her postpartum visits due to her prenatal and birth experiences.

Gender and Pregnancy

Gender is a very powerful social construct that impacts a person’s development. Society has constructed gender as a binary system (male/female) and assigned specific norms, rules, and expectations to what each gender should and should not be. Behaviors and practices that do not fit standard gender norms are often met with criticism, discrimination, and even hostility. People experience pregnancy differently depending on their gender identity. Gender impacts the way we treat the developing fetus and the cultural and social rituals associated with parenthood. It also impacts how we raise and socialize children. These experiences will be described in the following sections.

Gendering the Unborn Child

The role gender plays in a child’s life begins before they are born. In the past, many expecting parents would engage in cultural rituals or superstitions to determine the sex of the child. This might include the ring test, which requires a ring attached to a string. The way it moves determines whether the baby will be a boy or a girl. With the advancement of technology, expecting parents no longer need to guess their baby’s sex. They can know it relatively early in the pregnancy through ultrasound and genetic testing. Many parents do this and then host gender reveal parties and post the resulting videos on social media. Why are we so obsessed with gender?

As mentioned earlier, gender is a powerful social construct that influences the way we interact with the world. Knowing the sex of the baby early on helps parents and family determine the gender path for that child. Expecting parents are often pressured by their families and friends to reveal the sex of the baby so they can prepare for the baby’s arrival. Gender influences what clothes people will buy, the kind of toys they will purchase, and how they might decorate the nursery. On the surface, these types of distinctions may seem harmless, but it is important to connect gender to larger societal issues.

When we look deeper into gender construction, we see that biological sex is tied to assumptions about behavior, abilities, and genetics. We expect boys and girls to be and do certain things. Think about the messages we give girls when we decorate their rooms in “feminine” colors and give them dolls and a dollhouse to play with. Or about the messages we convey to boys when we decorate their rooms in “masculine” colors and give them a construction set and sports toys to play with. As a society, we may be enforcing narrow and often troublesome social stereotypes early on in a child’s development. We are telling girls that they are delicate, passive, and should sit and play with household items so that they can grow up and care for their homes. We tell boys that they are tough, active, and should learn skills so they can grow up and have careers. Moreover, we tell ourselves gender norms are essentially true because things “have always been this way” even though 100 years ago, boys were dressed in pink and girls in blue (Maglaty, 2011).

Gender socialization teaches children how to behave, how to dress, what types of jobs they can have, and how they should act towards individuals of the opposite gender. This puts undue limits and pressures on children rather than allowing them to determine their own paths in life. Children who do not conform to gender expectations are often bullied or ridiculed. They may develop issues related to gender identity and expression that impact them well into adulthood. It is important to think about the role of gender during pregnancy and throughout the development of the child.

Transgender Men

Transgender people account for 0.6 percent of the U.S. population (Williams Institute, 2022). Transgender pregnant men belong to an even smaller minority group, and they face specific challenges due to their gender identity. Many transgender men retain their female reproductive organs, which means they are able to get pregnant. Once pregnant, the level of care they need to maintain a healthy pregnancy and delivery is similar to cisgender pregnant women. Some transgender men choose to “transition” using hormone therapy. The use of testosterone may impact fertility as well as pregnancy (Gorton et al., 2005).

The stigmas and cultural pressures surrounding transgender pregnancy lead to misunderstanding and lack of care or empathy for this group. Some transgender pregnant men report not being taken seriously by medical staff or having to educate staff about their gender identity. These types of negative experiences can lead to behaviors that prevent transgender men from seeking prenatal and postpartum care. For example, a study concluded that 30.8 percent of transgender men delayed or did not seek support from health-care providers due to the prejudice and discrimination they experienced (Jafee et al., 2016).

Along with stigma in the medical world, transgender men also face scrutiny socially due to misconceptions and beliefs about gender. It is important to think about how social context and cultural norms impact this group. Transgender men deserve to have a healthy pregnancy and can have a positive experience given the appropriate support. The health-care system can educate providers about understanding the unique needs of diverse populations. Social norms and expectations can shift if we focus our attention on creating environments in which all children, and their caregivers, can thrive.

Cultural Perceptions and Age

In most societies worldwide, pregnancy elevates one’s social status. A pregnant woman is celebrated and becomes the ultimate symbol of womanhood and femininity. An expecting father is congratulated for his virility and masculinity. It is important to note that pregnancy is viewed differently depending on the context and time in history. Expectant mothers must navigate through all of these messages during one of the most important transitions of their lives. Age is one of the factors that plays a role in the perceptions and beliefs around motherhood.

Teenage Pregnancy

As authors we have heard many stories by our own friends and family members who have experienced abuse and lack of support by the professionals in charge of caring for them. Below, we will share a personal story to open the discussion around teenage pregnancy.

This young mother arrived at the hospital without family support. She experienced an intense amount of pain due to the child being breeched. When she asked for help, the nurse did not offer any relief. Finally, when the doctor arrived, he was visibly upset that the nurse had not offered pain medication or alerted him of the mother’s condition.

This mother ended up having an emergency C-section and was needlessly traumatized by the experience.

An important question that you might be wondering the answer to here is “why?” Why did this happen?

Cultural perceptions around pregnancy and pregnant mothers are demonstrated within social and familial interactions, the media, the work world, and in the medical field. These perceptions influence what we think mothers should be like, look like, and what they should do when they are pregnant. They also influence our thoughts and beliefs about who should be a mother and how they should mother. For example, modern Western society may view teenage pregnancy unfavorably because we believe that a teenager is unfit to parent.

A teenage mother or father may not be celebrated in the same way as an older person might be and will not earn any special social status, or support, as a result. On the contrary, as the story above showed, the expectant mother and father may encounter discrimination. Compare this to a teenage pregnancy 100 years ago. Not only would pregnancy during adolescence be considered normal, assuming the mother was married, but it would also be expected given the context of that period in time.

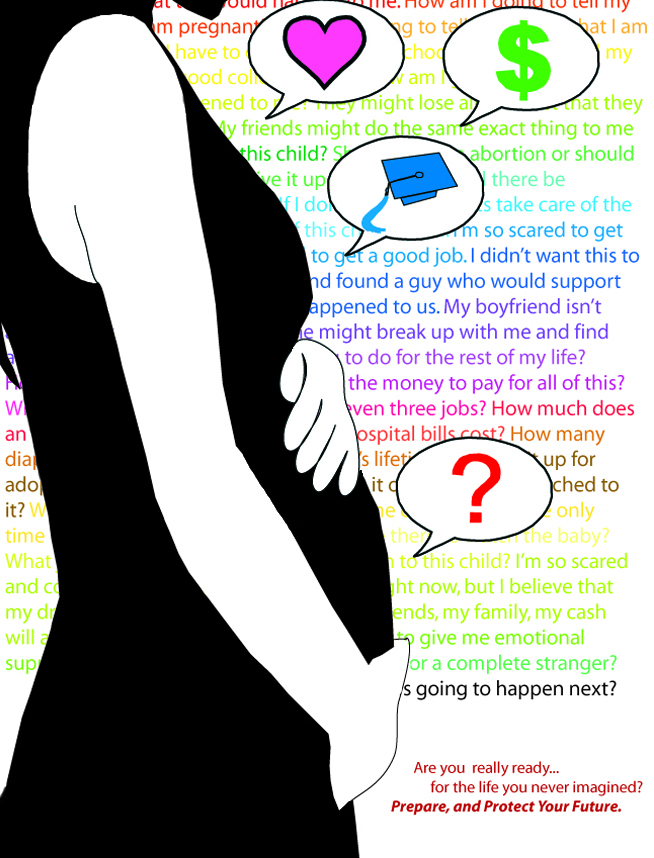

The mother in the scenario was young, but she was also Latina and the nurse was White. While racialized interactions are not a specific focus in this section, race plays a role in the way pregnant people are treated. Age further compounds these experiences. Teenage pregnancy is associated with a variety of stigmas and stereotypes that can be harmful to the pregnant mother and developing child (figure 3.7). They may be deemed irresponsible, financially and emotionally unstable or “bad.” They may face scrutiny by their families, peers, school staff, and medical professionals. This type of treatment can lead to negative coping behaviors such as avoiding prenatal care, missing school, or withdrawing from their friends and family.

There have been several studies that look into the connection between stigmatized teenage mothers and pregnancy outcomes. One such study shows that stigmatized pregnant mothers are at increased risk of abuse and social isolation (Weimann et al., 2005). Researchers who study stigmatized groups argue that these negative associations may be one of the underlying causes of health disparities. Stigmatized groups face increased stress, internalization of negative perceptions, lack of resources, and more (Hatzenbuelher et al., 2013). This impact is even more pronounced when teenage mothers have adverse experiences based on their race and social class.

It is important to understand the risk factors associated with teenage pregnancy, but it is more important to treat all expecting mothers and their partners with respect and dignity. Teenage mothers who receive adequate prenatal care and support from their family, friends, and community have positive outcomes during pregnancy, labor, and parenthood. Regardless of age, social class, or race, pregnant mothers of any age should get the level of health care they deserve.

Pregnancy in Advanced Maternal Age

Older pregnant women also face pressures associated with their age, although this differs from expecting teens. Despite the fact that women in today’s society delay pregnancy longer than ever before, stigmas exist for older women. Women are often questioned for their choice either not to have children at all or to have children after they have established careers, achieved financial stability, or satisfied some other personal requirement. Men who become fathers at older ages face little to no commentary regarding their choice to raise children later in life. The discrepancy between these perceptions is closely tied to gender norms and the expectations placed on women.

The term geriatric pregnancy has been used to describe the pregnancy of a woman over 35 years old. The term geriatric is also used to describe older adults, often aged 65 or older. The medical field now uses the term advanced maternal age to describe older expecting mothers. The associations between being an older mother and being a senior adult are clear and have negative associations. The age of 35 is used as a distinct marker for advanced maternal age, although there is no distinct age when a pregnancy suddenly becomes high risk. Rather, risk is associated with the gradual aging process.

Older women are often bombarded with messages that pregnancy in advanced age is dangerous or selfish, creating stigma around delayed pregnancy (Cardin, 2020). Risks associated with age are often exaggerated and do not take into account one’s individual choices, environmental and social circumstances, or genetics. Data does show that there are certain risks that increase with age, but most older women are able to have a healthy pregnancy without major complications (Chervenak, 1991). Modern medical advancements allow all pregnant people to access tests and procedures to measure risk or health issues, regardless of age.

There are many positive outcomes associated with delaying pregnancy and motherhood. A study concluded that older maternal age results in fewer behavioral and emotional issues in children, regardless of demographic and socioeconomic factors (Trillingsgaard & Sommer, 2018). Older parents are generally financially and emotionally stable, which leads to positive protective factors for children.

Licenses and Attributions for Pregnancy and Social Context

“Pregnancy and Social Context” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Case Study” by Christina Belli and Esmeralda Janeth Julyan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.7. Pregnancy Prevention Poster Design by Amanda on Flickr is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

a form of systemic injustice based on social identity resulting in social disadvantages and barriers to individuals and groups.