13.2 Theories

Understanding how teenagers think and their cognitive development is no easy task. Cognitive theories in adolescent development can provide a framework or set of statements that allow researchers, educators, and scientists to describe, explain, and predict outcomes or behaviors (see Chapter 2 for more information on theory). Understanding cognitive development through tested theories can help inform programs and policies impacting children in this developmental period.

Throughout the developmental period referred to as adolescence, cognitive processes continue expanding. As with any theory, a cognitive theory provides an empirically tested perspective on the understanding of how cognitive processes occur.

Piaget

Chapter 2 introduced Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development and how Piaget believed that humans develop in stages. As children make sense of the world around them, building on previous knowledge, they progress through four stages of cognitive development. According to Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, the fourth stage of cognitive development is the formal operational stage.

Formal Operational Stage

The formal operational stage of cognitive development begins at approximately 12 years old and lasts into adulthood. Children’s understanding and ability to make sense of the world move beyond just what can be seen or observed. In adolescence, young people often are able to think more abstractly and discuss abstract concepts such as beauty, love, freedom, and morality. Yet even in adulthood, the ability to think abstractly may not be constant. For some, formal schooling may stop at the age of 18, but exercising our cognitive abilities should not. Cognitive plasticity, or the ability of the brain and cognitive abilities to change over time, can cause some people to be less flexible in their thinking and to revert to concrete operational ways of thinking. Neural pathways can be created throughout our lifetime if we keep flexing our ability to do so.

Additional cognitive skills developed during the formal operational stage include hypothetical-deductive reasoning, which means that young people at this stage can develop a hypothesis based on what they think will logically occur. This hypothetical, what-if thinking is important for scientific thinking. Formal operational thinkers are able to consider potential outcomes and then test their hypothesis systematically. Additionally, adolescents develop transitivity, or the ability to understand the relationship between two objects. Transitivity allows adolescents to build on previous knowledge and problem-solve. The video in figure 13.1 illustrates deductive reasoning capabilities in different stages of cognitive development.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zjJdcXA1KH8

Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

Educational experiences, both in and out of the classroom, are important in developing abstract cognitive abilities. The day-to-day educational opportunities at school make schooling the main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. Guided learning through hypothetical problems posed by teachers encourages adolescents to reason and apply hypothetical thinking to problem-solving. Students move beyond basic understanding when they apply hypothetical reasoning and are able to create alternative explanations. Hypothetical thinking also provides students with the opportunity to broaden their understanding of other people’s experiences. For example, a social studies teacher using hypothetical-based pedagogy may ask students to imagine what it would be like to be enslaved during colonialism and write about their experience. Students have to apply what-if reasoning to narrate a hypothetical situation.

Piaget’s research on hypothetical reasoning often focused on scientific reasoning and problem-solving. The ability to systematically test and manipulate mental models of objects or processes is the precise skill that defines formal operations.

Students who are able to think hypothetically have an advantage as they require relatively few “props” to solve problems when completing schoolwork and can be more self-directed. This does not mean that academic success is out of reach for students who do not have this cognitive ability or that formal operational thinking guarantees academic achievement. All students have varying needs and strengths, and success is achieved when there is guided support along their educational journey.

Adolescent Egocentrism

During adolescence, individuals often demonstrate egocentrism, or a heightened self-focus. Adolescent egocentrism is characterized by an obsession with how one is being viewed or judged by others. For example, adolescents may spend a considerable amount of time checking social media posts for responses or likes.

David Elkind (1967) expanded Piaget’s theory of adolescent egocentrism by theorizing that the physical changes during puberty lead to a hyperfocus on appearance and behavior. Likewise, adolescents think others are as hyperfocused on them as they are on themselves. According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in the imaginary audience and the personal fable.

An adolescent’s belief that others are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as the adolescent causes the adolescent to anticipate the reactions of others and consequently construct an imaginary audience. The imaginary audience arises when individuals see themselves as the object of attention. They feel as if they are always on stage and under the scrutiny of others. This false perception of attention may be interpreted as being vain, but Elkind thought that the imaginary audience contributed to the self-consciousness that occurs during early adolescence. For example, it may be difficult for a pre-teen to think that no one notices a small pimple on their face. They are more likely to imagine that everyone is staring at the pimple on their face and thinking that they are “gross.”

The personal fable concept refers to the way adolescents tend to see themselves as unique or invulnerable and is another example of biased thinking that occurs during adolescence. Elkind explains that because adolescents feel like they are the center of attention (imaginary audience), they regard themselves and their feelings as being special and unique. Adolescents may believe that they are the only ones who experience such strong emotions. Perhaps you can recall feeling as if no one understood what you were experiencing. At one point or another, most adolescents have exclaimed, “You just don’t understand my life!”

The concept of personal fable and the belief in one’s uniqueness is what encourages adolescents to think they can handle or do anything. They see themselves as invulnerable to the consequences that other people have succumbed to. Research suggests that this is what removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016) and causes adolescents to make decisions that could involve serious health risks (Banerjee et al., 2015). Adolescents may be prone to engaging in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or having unprotected sex, because they believe they are invincible. These skewed, biased thoughts typically decline as individuals move into late adolescence and gain a greater understanding of themselves and the world around them.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

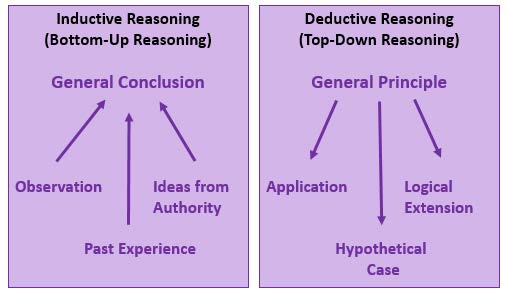

Inductive reasoning is the first type of reasoning to emerge in childhood. Inductive reasoning is sometimes characterized as “bottom-up processing.” It involves using specific observations or comments from those who are perceived to be knowledgeable to draw general conclusions. These conclusions may or may not be accurate. For example, a kindergartner watches middle schoolers in the neighborhood ride the bus to school. The kindergartner then concludes that all middle schoolers ride the bus to school.

In contrast, deductive reasoning, sometimes called “top-down-processing,” should emerge in adolescence. Deductive reasoning begins with a general principle that then leads to proposed conclusions. For example, if a general theory maintains that all trees are green, and you are then asked what color you expect a particular tree to be, deduction would lead you to say the tree should be green. In other words, you begin with a general principle that has been observed to be true (all trees are green), so the application and logical extension of this principle tells you that you can expect a particular tree to also be green (figure 13.2).

As adolescents gain the ability to think abstractly and hypothetically, they exhibit many new ways of reflecting on information (Dolgin, 2011). For example, they demonstrate greater introspection, or thinking about one’s thoughts and feelings. They may also begin to imagine how the world could be, which leads them to become idealistic or insist upon high standards of behavior. Because of their idealism, they may become critical of others, especially adults in their lives. Additionally, adolescents can demonstrate hypocrisy, or pretend to be what they are not. Since they are able to recognize what others expect of them, they will often conform to those expectations, even if that leads them to act in a way that is counter to their natural way of thinking or acting. Lastly, adolescents can exhibit pseudostupidity, which is when they apply a complex approach to a simple problem and fail as a result. Their new ability to consider alternatives is not completely under control, causing them to appear “stupid” when they are actually bright but inexperienced.

Vygotsky

Unlike Piaget, Vygotsky did not subscribe to the idea of developmental stages. Rather, he argued that development was cumulative and not a result specific to maturation (see Chapter 2 for more on Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory). According to Vygotsky, there are critical periods of cognitive growth, and in adolescence, the development of one’s own culture and beliefs occurs. Vygotsky believed that cultural tools support the development of reasoning and problem-solving skills as well as adolescents’ own “cultural tool kit.”

Cultural Tools

According to his sociocultural theory, Vygotsky believed that development was a result of social interactions with people and cultural artifacts, such as language, signs, and symbols. In adolescence, these influences, which Vygotsky referred to as cultural tools, provide context, integration, and even intersect with the development of one’s own culture. The mental processing involved in these social interactions supports Vygotsky’s belief that cultural tools also provide opportunities for cognitive development. Vygotsky believed that adolescents develop increased cognitive abilities, such as focused attention, memory, formal reasoning, and verbal thinking, through social interactions. He emphasized language as being an important cultural tool for cognitive development. According to Vygotsky (1962), language plays two important roles in cognitive development by doing the following:

- enabling adults to transmit information to children

- providing opportunities for cognitive adaptation

Vygotsky in the Classroom

Reciprocal teaching is a contemporary teaching approach based on Vygotsky’s work. In reciprocal teaching, students and teachers collaborate in the learning process, with the teacher’s role diminishing over time. Students deepen their understanding and gain confidence in their learning when they explain their methods and conclusions to others and receive feedback. Research has shown that students can develop their math skills, their social awareness, and their relationship skills by alternately taking on the roles of coach and player as they explore math concepts and problems with a partner.

Visit Digital Promise [Website] for more information on reciprocal teaching, including a short video of how this method can be applied to middle to high school mathematics.

Spontaneous and Scientific Thinking

The development of abstract, hypothetical thinking in adolescence is relevant to Vygotsky’s beliefs about both spontaneous thinking and scientific thinking. Vygotsky believed that everyday experiences pave the way for unplanned, organic scientific thinking, or spontaneous concepts, through reflection and cultural tools, such as language, writing, and math.

Critical Periods

Vygotsky subscribed to what he called “critical periods,” which are human developmental periods of transition and cognitive restructuring. Vygotsky did not see these periods as periods of growth, but rather as periods of “constructive processes of development” (Vygotsky 1998, p. 194). According to Vygotsky, the final critical period occurs in adolescence around the age of 13. This adolescent critical period is characterized by the change from concrete to abstract thought, as well as a shift away from the fantasy play common in younger children and toward play involving games with rules.

Gaps and Limitations

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development suggests that cognitive development is complete by the age of 12. However, most recent research demonstrates that adolescence is a period of important cognitive increases. Furthermore, although structural cognitive development reaches a peak during childhood, functional cognitive development can continue throughout one’s lifetime. Piaget’s theory of cognitive development is vague regarding mechanisms and processes of change, but it created the building blocks for empirical research on cognitive development and neuroscience today.

Vygotsky’s approach to the critical period in adolescence is similarly vague and fails to identify the mechanism that causes the cognitive restructuring during this developmental period.

Licenses and Attributions for Theories

“Theories” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Piaget” is remixed and adapted from 14.3: Cognitive Theorists- Piaget, Elkind, Kohlberg, and Gilligan is shared under a CC BY license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Paris, Ricardo, Raymond, & Johnson (College of the Canyons); 6.6: Cognitive Development in Adolescence is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Martha Lally & Suzanne Valentine-French; Lifespan Development by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted; and Psychology Through the Lifespan by Alisa Beyer and Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Vygotsky” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0 excluding “Vygotsky in the Classroom” text box which is adapted from Reciprocal Teaching by Digital Promise and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

“Gaps and Limitations” by Kelly Hoke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 13.1. Piaget – Stage 4 – Formal – Deductive Reasoning.

Figure 13.2. Inductive and Deductive Reasoning by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 13.3. “Sarajevo, Bosnia” by Kashklick is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

a process by which children acquire and process information and then learn how to use it in their environment.