13.3 Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Cognitive skills continue to expand in adolescence, although each child develops at their own rate.

Adolescents will develop their own worldview, influencing their thinking and metacognition. We know that adolescents are in the formal operational stage of cognitive development. During adolescence, teenagers move beyond concrete thinking and become capable of abstract thought. Teen thinking is also characterized by the ability to consider multiple points of view, imagine hypothetical situations, debate ideas and opinions, and form new ideas. In addition, it’s not uncommon for adolescents to question authority or challenge established societal norms. The following section will further explore the expanding cognitive processes related to adolescence, including executive function and attention, and how environmental stressors can impact cognitive processing.

Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model provides further context for developing cognitive processes as a child’s microsystem further expands during this period as they begin to plan and make strides toward adulthood. Adolescents may begin driving, working, registering to vote, getting involved with social or political concerns, enlisting in the military, or planning for college or vocational school. Additionally, a teen’s microsystem begins shifting away from their immediate family as peers and romantic interests play a larger role in their lives.

Executive Function

Executive functions, including attention, working memory, and cognitive flexibility, have been steadily improving since early childhood. Studies have found that executive function is very competent in adolescence. However, self-regulation, or the ability to control impulses, may still fail. A failure in self-regulation is especially true when there is high stress or high demand on mental functions (Luciano & Collins, 2012). While high stress or demand may tax even an adult’s self-regulatory abilities, neurological changes in the adolescent brain may make teens particularly prone to more risky decision-making under these conditions. Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in the following five areas during adolescence:

- attention: improvements in both selective attention and divided attention

- memory: improvements in working memory and long-term memory

- processing speed: improvements in information processing speed, which increases sharply between age 5 and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood

- organization: improvements in awareness of thought processes and use of mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently

- metacognition: improvements in the ability to think about thinking itself, including the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events

Activity: Information Processing Model

In previous chapters, the information processing model was discussed. During adolescence, memory and the skills to acquire new information continue developing. Review how information is processed, types of memory, and how this relates to cognitive development during this period of development.

Metacognition

Thinking about thinking is referred to as metacognition. Adolescents become more reflective and can understand complex relationships between ideas and people. Metacognition abilities vary among adolescents and adults based on their capacity to evaluate situations objectively. Adolescents are better able to understand than younger children that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. The ability to be introspective may lead to forms of egocentrism or self-focus.

Neuroimaging shows that different areas of the brain are responsible for cognitive processing and emotional processing (Brock et al., 2009). Collectively, these processes are known as executive functioning (EF). Cognitive processes are called “cool EF” (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Cool EF includes attention, metacognition, problem-solving, and working memory. Emotional processes are called “hot EF” (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). Hot EF relates to self-control, self-regulation, impulsivity, perspective taking, and engagement in inappropriate versus appropriate behavior (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018).

Biological and behavioral development support the notion that the hot and cool EF trajectories are different. Frontal cortex development and myelination continue through adolescence (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018, p. 262). Neural pathways and brain areas associated with emotion regulation develop later than other systems, supporting the idea that the cool EF system activates before the hot EF system (Bjorklund & Causey, 2018, p. 262; Brock et al., 2009). The hot EF system is more difficult to use, and it takes longer to develop (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). One study found that when a task was reframed from a “hot ef” representation (emotionally charged) to a “cool ef” representation (more neutral), it was much easier for the children to engage with and be successful at the task (Zelazo & Carlson, 2012). For example, the task of preparing for an upcoming test, when approached from a “hot ef” context might become focused on all the social interactions that will be lost due to study time; the same task, when approached from a “cool ef” may be focused on the specific topics that need to be reviewed. These findings suggest that having to operate from the hot EF system places greater demands on the child. Having an awareness of children’s hot and cool EF systems is important for understanding how best to interact with them, both personally or professionally, such as in an educational setting.

While metacognition is still developing throughout adolescence, it typically peaks just after late adolescence, making it a useful strategy for learning in and out of school (Hitomi dos Santos Kawata et al., 2021). Out of the classroom in everyday decision-making, metacognition allows adolescents to discern information as helpful or misleading (Moses-Payne et al., 2021). In the classroom, metacognition assists in learning. Practicing metacognition in the classroom can help students achieve agency over their learning and allows students to transfer learned information across varying contexts. Classroom practices that support metacognition include:

- identifying clear learning goals

- employing motivational strategies for deferred gratification

- scaffolding or using progression in instruction

- modeling the use of metacognitive strategies (e.g., think-aloud)

- using reciprocal teaching

- encouraging reflection and evaluation

Pruning

Adolescence is one of the few periods when the brain is rapidly producing a large number of brain cells—more than it needs, in fact. While these extra brain cells provide extra storage for information, they also can decrease efficiency (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). To become more efficient, the brain continues to form new neural connections. It also becomes faster through pruning. The process of pruning rids the brains of unused neurons and connections, and produces myelin, the fatty tissue that forms around axons and neurons, which helps speed transmissions between different regions of the brain (Blakemore, 2008; Rapoport et al., 1999). This video discusses brain remodeling and describes how pruning assists in executive function and efficiency in cognitive development:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbCvQbBi2G8

Emerging research suggests that excessive pruning in adolescence may be linked to certain mental health conditions, such as schizophrenia. Optional resources:

- Dr. Steve McCarroll and his team at Harvard are exploring the specialization of cell types related to schizophrenia and pruning: Steve McCarroll: How data is helping us unravel the mysteries of the brain | TED Talk [Streaming Video].

- This article explores the C4 protein and environmental factors that can further lead to excessive pruning related to schizophrenia: Abnormal synaptic pruning during adolescence underlying the development of psychotic disorders [Website].

Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is the act of analyzing information presented as facts, evidence, or arguments and being able to make a decision. Critical thinking requires an individual to assess the reliability and validity of information and evaluate the ideas and arguments. Critical thinkers ask key questions, evaluate the evidence, use logical and objective reasoning to problem solve, and synthesize the information so they can communicate their ideas clearly. Critical thinking skills are applicable in many aspects of an adolescent’s life, including school, social interactions, and work.

Critical thinking requires the ability to clearly express oneself in spoken and written communication, both of which adolescents have the opportunity to develop and demonstrate in school. Adolescents are expected to display critical thinking and associated cognitive skills, such as metacognition, both in school and out. For example, in school, adolescents must be able to communicate synthesized information in written assignments. To do this, students must be able to evaluate sources and information accessed online. The strategies they use for thinking about thinking (metacognition) in the evaluation process will define the quality of the outcome.

Critical thinking is not fully established in adolescence and is something to be practiced. Guided learning in school enables students to gain the experience necessary to expand their knowledge, including understanding their learning processes and evaluating their learning outcomes. These two defining qualities of metacognition are part of critical thinking as well. Teachers can foster critical thinking in students through discussions and written assignments. By learning to reflect, construct, and control their own ideas, rather than allowing ideas to control them, students can improve their ability to understand information from a deeper context. For students who face barriers in written or expressive language, accommodations can be made to support the development of critical thinking by utilizing resources the student may already be accessing, such as speech or occupational therapy.

Relativistic Thinking

Beyond critical thinking, adolescents are also more likely to engage in relativistic thinking, which is the ability to acknowledge that some truths are context-dependent. They are more likely to question others’ assertions and less likely to accept information as the absolute truth. As they interact more with people outside their family circle, they learn that the rules they believed to be absolute are actually dependent on family and culture. They begin to differentiate between rules crafted from common sense, like don’t touch a hot stove, and those that are based on culturally dependent standards, like a family’s code of etiquette. This acknowledgement of multiple truths and context-dependent norms can lead to the questioning of authority in all domains.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as a dual-process model, which is the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Albert & Steinberg, 2011). Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional (Kahneman, 2011). In contrast, analytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational. While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier and more commonly used in everyday life. It is also more commonly used by children and teens than by adults (Klaczynski, 2001). The quickness of adolescent thought, along with the maturation of the limbic system, may make teens more prone to emotionally intuitive thinking than adults.

As critical thinking develops in adolescence, adolescents can utilize strategies for problem-solving. Heuristics are cognitive shortcuts and can be thought of as aids in decision-making. They allow us to reach a solution without a lot of cognitive effort or time, and they can aid in both our intuitive and analytical thinking. Heuristic thinking is essentially an educated guess about something. We use heuristics all the time, such as when deciding what groceries to buy from the supermarket, when looking for a library book, when choosing the best route to drive through town to avoid traffic congestion, and so on. However, while heuristics are often useful, they may lead to errors as they are often based on biased information, such as personal experience. Furthermore, the main benefit of heuristics—helping us make decisions quickly and fairly easily—is also its potential downfall: the quick and easy solution is not necessarily the best solution.

Cognitive Empathy

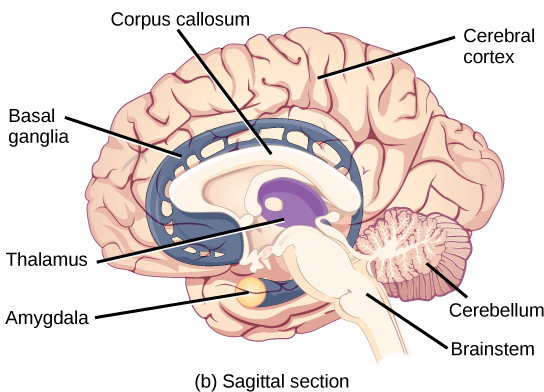

Cognitive empathy relates to the ability to take the perspective of others and feel concern for others (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2005). Cognitive empathy has developmental gains in early childhood and changes across the lifespan. However, studies are mixed regarding whether or not cognitive empathy increases during adolescence (Doris et al., 2022; Van der Graaff et al., 2013). Cognitive empathy is an important component of social problem-solving and conflict avoidance. Studies show that in caregiver-adolescent relationships, modeling perspective taking and validating teenagers’ feelings can support the development of cognitive empathy (Main, Paxton, and Dale, 2016; Main et al., 2019). The limbic system fully matures in early adolescence and is associated with emotional processing (figure 13.6). However, perspective taking relies on the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with critical thinking. The prefrontal cortex does not mature until adulthood.

Impulse Control

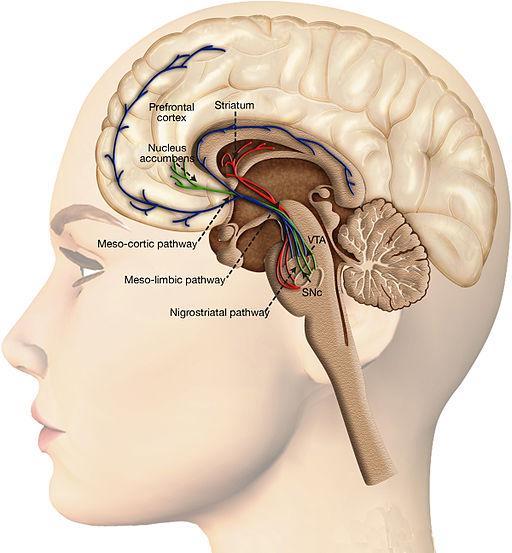

During adolescence, two influential changes occur in the brain, impacting cognitive abilities and how individuals view risk and reward. One change is within the prefrontal cortex, which undergoes significant development during this period. The other change involves dopamine, a neurotransmitter in the brain that produces feelings of pleasure, which can contribute to increases in adolescents’ sensation-seeking and reward motivation (figure 13.7).

The prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain responsible for critical thinking, judgment formation, impulse control, and emotional regulation, continues to develop in adolescence (Goldberg, 2001). Even though critical thinking skills are emerging in adolescence, individuals at this age often decide to engage in activities that produce high levels of dopamine, without fully considering the consequences. The timing of the development of the prefrontal cortex contributes to risk-taking during middle adolescence because adolescents are motivated to seek thrills (Steinberg, 2008). One of the world’s leading experts on adolescent development, Laurence Steinberg, likens this to engaging a powerful engine before the braking system is in place. The result is that adolescents are more prone to risky behaviors than children or adults, likely because they place greater value on rewards. Furthermore, adolescents highly value social connection, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to reward those values than to long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

However, adolescent impulsivity is sometimes due not to a lack of brakes, but to the planned and enjoyable pressure to the accelerator. Adolescents are making choices influenced by a very different mix of chemical influences than their adult counterparts—a hopped-up reward system that can drown out warning signals about risk. Young people need to somewhat enjoy the thrill of risk-taking to complete the incredibly overwhelming task of growing up.

It is helpful to put all of these brain processes in a developmental context. In summary, changes in brain development, information processing, and hormonal changes lead adolescents to:

- focus on the present

- engage in risk-taking behaviors

- feel invulnerable

- seeking out novel, adventurous, and varied experiences

Licenses and Attributions for Cognitive Development in Adolescence

“Cognitive Development” and subsections remixed and adapted from:

Lifespan Development by Julie Lazzara is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Human Behavior and the Social Environment I by Susan Tyler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted and from You Don’t Say? Developmental Science Offers Answers to Questions About How Nurture Matters by Emily Spalding is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Child Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Adolescent Development by Jennifer Lansford is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. Permissions beyond the scope of this license may be available in our Licensing Agreement.

“Steve McCarroll: How data is helping us unravel the mysteries of the brain | TED Talk.” License Terms: CC BY — NC — ND 4.0 International.

Figure 13.4. Information processing model: Sensory, working, and long term memory | MCAT | Khan Academy.

Figure 13.5. Shannon Odell: What’s the smartest age? | TED Talk License Terms: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International.

Figure 13.6. The Limbic System Adolescence by Martha Lally, Suzanne Valentine-French, and Diana Lang is licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 13.7. Dopaminergic system and reward processing in Wikimedia Commons licensed CC-BY-4.0.

a process by which children acquire and process information and then learn how to use it in their environment.