5.2 Cognitive Development

It was once believed that infants were born as blank slates and relied only on their senses to learn about the world. As we saw in the last chapter, newborns already have many capabilities and use both inherited information and environmental information to form thoughts, beliefs, and understanding. Every experience they encounter, such as cuddling with a caregiver, listening to conversations, or tasting new foods, provides an opportunity to learn. Due to this innate drive, children’s brains go through rapid changes during the first 3 years of life.

Cognitive development refers to the way children take in and process information, acquire knowledge and skills, and use information to problem solve. These processes and skills gradually become more complex as the child grows. As referenced in Chapter 1, children were once viewed as mini-adults, and there was very little knowledge about the unique ways in which they learn. Researchers now understand that children do not process information like adults, nor do they think in the same way as adults. They also understand that young children’s cognitive development relies heavily on interactions with their caregivers and the experiences they are exposed to in the first 3 years of life.

Infants and toddlers are constantly confronted with new stimuli. To make sense of their worlds, their brains are designed to organize this information in meaningful ways. Children use schemas, or categories of knowledge, to make sense of and process information efficiently. For example, a child may form a schema about what a dog is based on the dog they have at home. Because their dog is brown and has a tail, they believe that all dogs are brown and have tails. When they visit a family member, they see a brown cat with a tail and call it a dog. Eventually, the child will learn the differences between dogs and cats. They will alter their schema about dogs and form a new schema about cats.

Schemas are modified based on the type of information a child encounters. Assimilation occurs when a current schema is applied to understand something new. In the example above, this is when the child thinks that the cat is a dog. Accommodation occurs when an existing schema is updated or when the child has to create a different schema because the new information does not fit into the current schema. This is when the child forms a schema about what cats are. Schemas are fantastic tools for learning, but they also help us with other cognitive functions, such as attention and memory.

Let’s take a look at the foundational structure used for cognitive learning—the brain.

The Growing Brain

The brain is a complex structure that allows us to do all of the wonderful things humans do. Around 3 weeks after conception, we start to form our brain and nervous system. Children are born with billions of brain cells that transmit information to their bodies. Neurons are brain cells that send signals to the nervous system. Genetics and epigenetics play a big role in early brain formation and determine how many neurons a child starts off with and their arrangement within the brain (Graham & Forstadt, 2011). The experiences and interactions a child has determines whether the connections between neurons, or synapses, are strengthened or weakened. If neurons are like wires, then we can think of synapses as electrical signals that connect the wires and help relay information.

At least one million new neural connections are made every second, more than at any other time in life (Zero to Three, 2023). The brain goes through a rapid development during the first 3 years of life, and certain brain connections reach their peak. At birth, the number of synapses per neuron is 2,500, but by age 2 or 3, it’s about 15,000 per neuron (Graham & Forstadt, 2011). These peaks are known as sensitive periods of development. Vision, for example, exists when a child is born, but the neuron connections peak at around 8 months. Early visual stimulation causes the neurons and synapses associated with vision to grow and get stronger during this age. This is around the time when we notice infants becoming more aware of the world around them.

Synaptic pruning refers to the process by which the brain eliminates certain neural connections and strengthens others. This process helps the brain become more efficient and helps the child thrive in their respective environments. Once our brain has completed its overall growth in adulthood, we will lose around 40 percent of these connections due to synaptic pruning (Webb et al., 2001). The phrase “use it or lose it” is applicable when it comes to how the brain is wired. Connections that are used often will become permanent within the brain, while connections that are not used will not fully develop.

It is important to note that although there are sensitive periods of brain development, scientists have learned that the brain is highly plastic throughout our lives. Brain plasticity, or neuroplasticity, “is a process that involves adaptive structural and functional changes to the brain” (Puderbaugh & Emmady, 2022). This process means that the brain can continue to grow and rewire itself, even when exposed to adverse experiences or trauma. This is especially true during childhood when the brain is more plastic.

The brain experiences two types of neuroplasticity. The first is called experience-expectant plasticity, which is when stimuli from the environment guide normal brain development, especially during sensitive periods. This type of plasticity occurs mostly during early postnatal development. An infant who experiences being held by their caregivers, seeing different faces or objects, or hearing spoken language will generate experience-expectant plasticity.

The second type of neuroplasticity is experience-dependent plasticity, which is when the brain is remodeled due to unique or unexpected experiences. This type of plasticity can occur during or outside of sensitive periods of development, in childhood or adulthood. Learning a new skill, such as how to play an instrument or a specific sport, would guide experience-dependent learning. This is also the type of plasticity that responds to stress or trauma within a child’s environment.

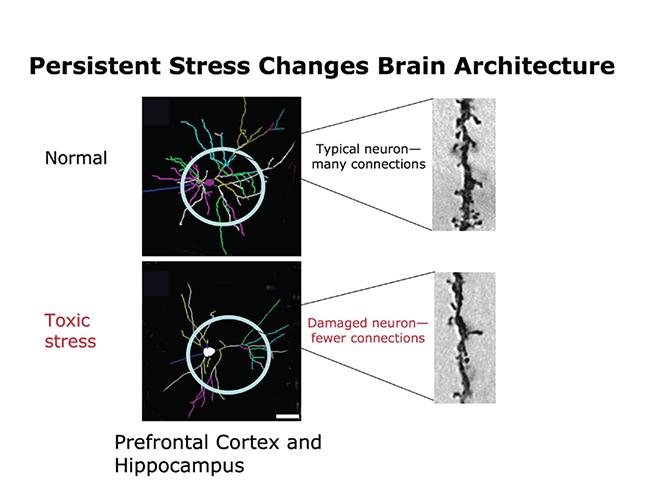

All young children experience stress to some degree, such as when they’re hungry, get hurt, or attempt something new. This type of stress is considered normal and healthy when combined with adequate parental response. In contrast, chronic or toxic stress is damaging to the developing brain. Toxic stress is stress that results in “excessive or prolonged activation of stress response systems in the body and brain” (Center on the Developing Child, 2015). For example, children may experience toxic stress if there is no response to their distress, if they experience child abuse or neglect, or if they lack survival basics, such as food, water, and safety. Toxic stress damages neural connections in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus regions (figure 5.1). These regions are responsible for a variety of processes, such as problem solving, attention, and memory.

Chronic stress causes the brain to produce cortisol, known as the stress hormone. Babies who are exposed to high levels of cortisol can experience disruptions in their learning and may exhibit behavior problems and even health issues later in life. Luckily, there are protective factors that can mediate the impact of stress on the brain and body. For example, researchers note that responsive parenting can protect young children from the negative impact of stress (Asok et al., 2013).

In figure 5.1, we can see how brain architecture changes based on experience. Studies demonstrate that brains that are subjected to toxic stress have underdeveloped neural connections in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. These structures are important for learning, memory, and behavior. Brains that are not subjected to toxic stress show many healthy functioning neural connections.

We know that genes, experiences, and environmental stressors impact a child’s growing brain, but what about exposure to technology? The use of technology in everyday life is a relatively recent development within the span of human existence. Screen time, or a person’s use of electronic devices with a screen such as a phone, laptop, or television, has become a regular part of American society. Many of the educators we work with have expressed concern over the use of screen time, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated social restrictions and increases in remote learning. A report by Common Sense Media states that infants and toddlers spend an average of 49 minutes to 2 hours and 30 minutes on screen media daily, and that usage increases for boys and lower-income children (Rideout & Robb, 2020).

The World Health Organization recommends that children under the age of 1 year get zero sedentary screen time and that children ages 1–3 get 1 hour or less of sedentary screen time per day (WHO, 2019). As we can see, young children are getting much more than the recommended amount of screen time. How does this impact a child’s brain development? A recent study of 47 children showed that increased screen time was associated with underdeveloped or disorganized white brain matter (Hutton et al, 2019). This is a significant finding given that white matter supports the formation of executive functions, language, and literacy skills within the brain. While the sample size of this study was small, it suggests the importance of studying how screen time impacts a child’s brain, especially during infancy and toddlerhood.

Moral Development

As infants and toddlers grow, they will develop a sense of what is acceptable in their world. The development of morality is dependent on a child’s cognitive functions and growth. Children engage in a thinking process when they encounter a moral situation, which helps them determine right from wrong. Moral development also occurs through children’s interaction with their social and environmental contexts. Theorist Uri Bronfenbrenner (1992) describes five interrelated systems, which include:

- microsystem (family, peers)

- mesosystem (interaction between child, family, community)

- exosystem (neighborhood, media)

- macrosystem (wealth, poverty, race)

- chronosystem (major life changes, history)

A child’s core beliefs, temperament, and life experiences can all influence their sense of morality. Every day, children are surrounded by people and situations that guide their moral development. These situations could involve interactions with siblings or peers, or watching scenes from a show or movie. Caregivers play a major role in the early moral development of infants and toddlers. Children will observe the actions and intentions of the adults around them to gain an understanding of how to respond to situations. Young children are rapidly developing cognitive skills, but their logical and reasoning abilities are still immature.

Theorist Lawrence Kohlberg believed that young children learn what is acceptable or not acceptable based on the punishments or rewards that occur after a behavior or situation (Kohlberg & Hersh, 1977). For example, a child might learn that it is not okay to hit their sibling because they are sent to time-out each time they do. Around 2 years old, children start to feel moral emotions and understand, at least somewhat, the difference between right and wrong. Part of this immaturity involves the way that empathy is developed. Young children are motivated by the threat of consequences. Therefore, early on in their moral development, you might see that they are more concerned with being punished rather than the feelings of another person. A young child might also show signs of empathy if they see another child who is upset, but generally, empathy does not develop until the preschool years.

Moral development is gradual and adaptive. Patient caregivers use opportunities to teach children about expectations and right from wrong. For example, if a child behaves or communicates in a way that is not socially acceptable, the caregiver can use this time to help the child learn. Infants and toddlers make small moral choices daily, such as when they decide whether to share a toy or think about taking an extra candy when their parent is not looking. It is important for caregivers to avoid shaming a child when they do something wrong. With proper care and guidance, young children will eventually be able to regulate their own sense of morality.

Licenses and Attributions for Cognitive Development

“Cognitive Development Introduction” by Christina Belli and Esmeralda Janeth Julyan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“The Growing Brain” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Moral Development” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.1. Credit: Center on the Developing Child.

a process by which children acquire and process information and then learn how to use it in their environment.

a process by which children process their understanding of right and wrong as related to their social and environmental contexts.