7.6 Physical Development in the Preschool Years

Play is the business of preschoolers. In order for them to become competent in playing and interacting with their environment, they must go through significant changes in their bodies and physical abilities. Preschooler bodies tend to be more proportioned and look more adult-like than baby-like. They are able to move their bodies in more sophisticated ways, and we see a marked improvement in the balance and coordination.

Let’s take a look at what’s happening in a preschooler’s physical development by examining the growing body.

The Growing Body

Children’s bodies are continuing to develop throughout the preschool years, but we may see things slow down a bit compared to the rate of growth during infancy and toddlerhood. One thing immediately noticeable is that children start the preschool years with all 20 of their teeth. Children will experience widening of the mouth and jaw to make room for permanent teeth (AAP, 2012). This will make a preschooler’s facial features appear more distinct and mature.

A 3-year-old preschooler will still present with a large head compared to the rest of their body and will look more like a toddler than a preschooler. Their bodies eventually become more proportioned. Preschoolers start to lose their “baby fat” and start to gain more muscle (AAP, 2012). The typical growth for 3- to 6-year-olds includes gains of 4–5 lb. (113.4 to 141.8 g) per year, 2–3 in. (5.1–7.6 cm) in length per year, and 20/20 (or perfect vision) capabilities by 4 years old (MedlinePlus, 2023).

By now, most preschoolers have achieved control of their bladder and bowel muscles and are potty trained. It is common for preschoolers to have accidents, especially at night, as children practice staying dry for long periods of time. The American Academy of Pediatrics states that there are three common reasons why children will have accidents at night (AAP, 2021):

- Communication between the brain and bladder: If the bladder signals to the brain that it’s filling up with urine, but the brain doesn’t send a message back to the bladder to relax and hold the urine until morning, bedwetting will happen. Likewise, if the bladder signals to the brain that it’s filling up with urine, but the brain doesn’t hear the signals, which is especially common during deep sleep, bedwetting will happen.

- Stress or trauma: Children who have previously been dry at night may have bouts of bedwetting when they experience stress or traumatic events or when they get sick or constipated. This is a different problem than the child who has never been dry at night. Children with these short-term episodes of bedwetting usually have dry nights when the underlying problem resolves.

- Medical concerns: Rarely, some children begin to wet the bed as a result of a serious medical problem.

Preschoolers require adequate amounts of sleep to recharge their bodies each day. The CDC recommends that children ages 3–5 get 10–13 hours per 24 hours, including naps (CDC, 2022). When children get the proper amount of sleep, they are more alert, have improved cognitive functions, and are able to regulate themselves (Pacheco, 2023).

Preschoolers also require a healthy and balanced diet that includes fruits and vegetables, which provide young bodies with vitamins and minerals to support growth and immune function. Children who do not get adequate nutrition may experience growth delays. Lack of nutrition and sleep can lead to long-term consequences if not addressed early.

Motor Development

The preschool years are notorious for motor skill refinement. Preschoolers are especially attracted to motion and song. Their days are filled with jumping, running, swinging, and clapping. They turn every space into a playground, which may mean climbing on a chair at the dining table or sliding underneath a booth at a restaurant. Of course, this can be frustrating to a caregiver, but it’s the business of children at this stage.

Children generally continue to improve their gross motor skills during this time, including their abilities to jump, run, and kick a ball. Caregivers are frequently asked by children to “look at me,” while they hop or roll down a hill. Children’s songs are often accompanied by arm and leg movements or cues to turn around or move from left to right.

The gross motor milestone chart below (figure 7.7) shows the progression of gross motor skills that children will typically develop during the preschool years.

| Typical Age | What Most Children Do by This Age |

|---|---|

| 3 years |

|

| 4 years |

|

| 5 years |

|

There are many activities focused on play that young children enjoy and that support their gross motor skill development, including:

- tricycles

- slides

- swings

- sit-n-spin

- mini trampolines

- bowling pins (can use plastic soda bottles also)

- tents (throwing blankets over chairs and other furniture to make a fort)

- playground ladders

- suspension bridges on playgrounds

- tunnels (try throwing a bean bag chair underneath for a greater challenge)

- ball play (kick, throw, and catch)

- Simon Says

- target games with bean bags and balls

- music

- scooters or skateboards

Fine motor skills are also being refined as children continue to develop more dexterity, strength, and endurance. Fine motor skills are very important as they are foundational to self-help skills, such as tying a shoelace, and later academic abilities, such as writing.

Figure 7.8 shows how fine motor skills progress during early childhood for children who are developing typically.

| Typical Age | What Most Children Do by This Age |

|---|---|

| 3 years |

|

| 4 years |

|

| 5 years |

|

Here are some fun activities that will help children continue to refine their fine motor abilities. Fine motor skills are slower to develop than gross motor skills, so it is important to have age-appropriate expectations and play-based activities for children, such as:

- pouring water into a container

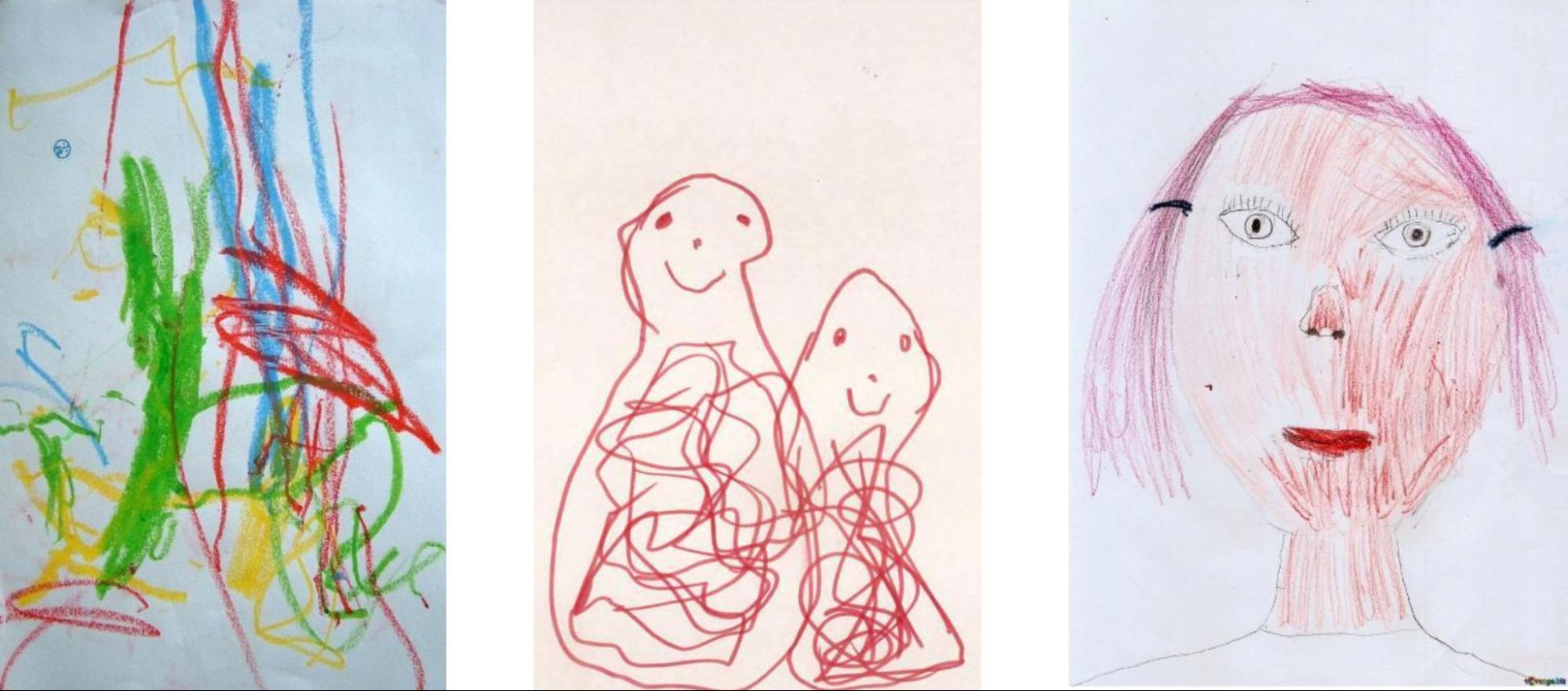

- drawing and coloring (figure 7.9)

- using scissors

- finger painting

- fingerplays and songs (such as the “Itsy Bitsy Spider”)

- using play dough

- lacing and beading

- practicing with large tweezers, tongs, and eye droppers

The development of visual pathways is represented in changes in children’s drawings. As the brain of a child matures, the images in their drawings become more detailed as they expand their ability to visualize in their head what they are creating on paper. For example, children initially practice simple motor skills by drawing scribbles and dots, without connecting the image being visualized to the scribbles created on the paper (figure 7.9, left). By about age 3, the child begins to draw creatures with heads but not many other details (figure 7.9, middle). Gradually, pictures begin to have more details, such as arms and faces with a nose, lips, and eventually eyelashes (figure 7.9, right).

Licenses and Attributions for Physical Development in the Preschool Years

“Physical Development in the Preschool Years” by Christina Belli is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Motor Development” from Child Growth and Development Authored and compiled by Jennifer Paris, Antoinette Ricardo, & Dawn Rymond is licensed under CC BY 4.0; minor edits.

Figure 7.5. Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash.

Figure 7.6. Developmental Milestones by the CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 7.7. Developmental Milestones by the CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 7.9. Left: Image by Wikimedia is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. Middle: Image by torange.biz is licensed under CC-BY 4.0. Right: Image by torange.biz is licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

a process in which children’s brains and bodies grow to help them engage with and thrive in their environment.