1.4 Social Identities, Social Constructions, and Families

In this section we will start by exploring social identities. Then we will analyze the ways that socially constructed differences contribute to the ways that individuals and families experience power, privilege, discrimination, and oppression.

Social Identities

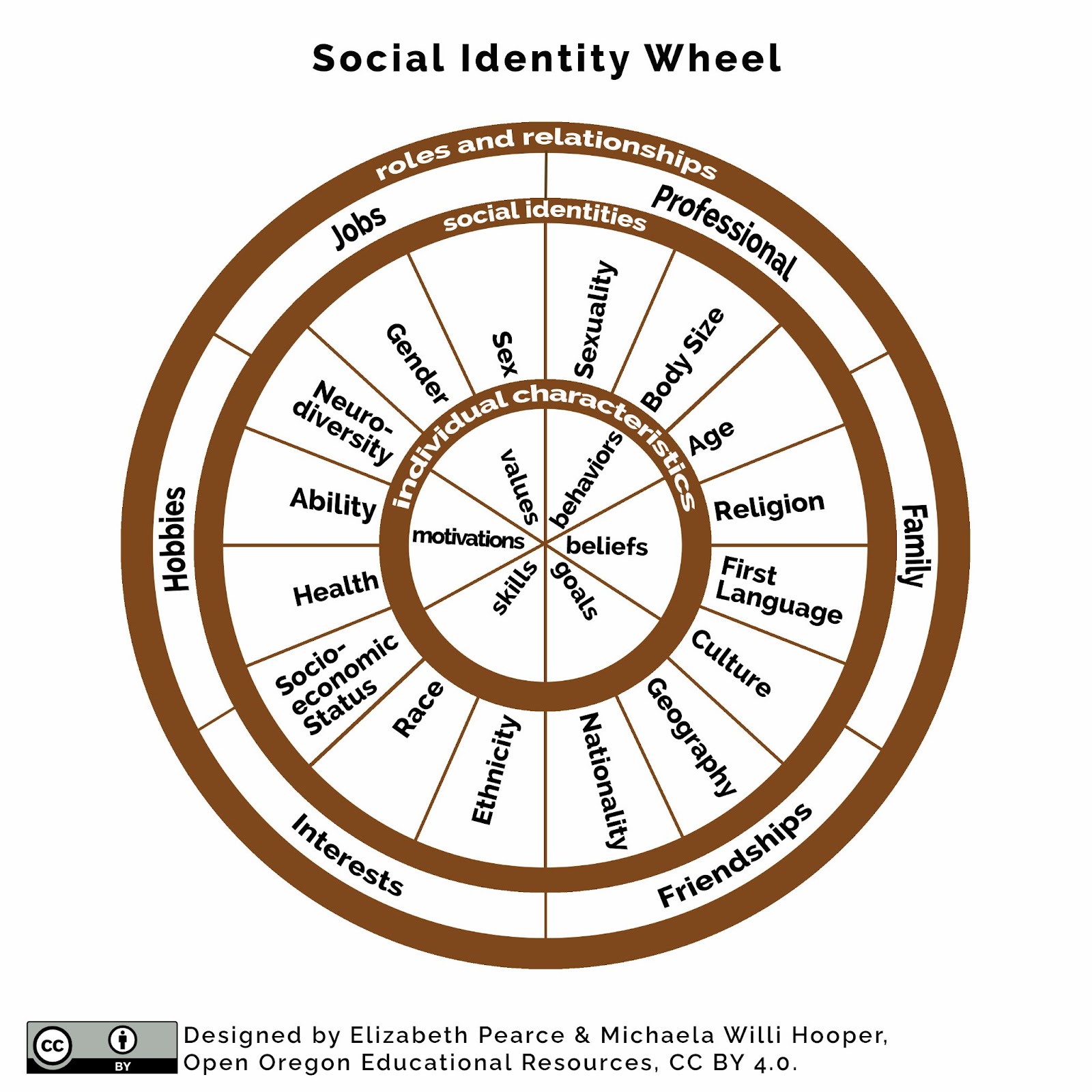

Families are made up of individuals, and each individual possesses a unique identity (Figure 1.16). An identity consists of the combination of individual characteristics, social characteristics or identities, roles, and relationships with which a person identifies. Let’s break down each of those aspects of social identity:

- Individual characteristics are integral to a person’s values, beliefs, and motivations.

- Social characteristics or social identities can be biologically determined and/or socially constructed. Sex, gender, race, ethnicity, ability, age, sexuality, nationality, first language, and religion are all social characteristics.

- Roles and relationships indicate the behaviors and patterns used when interacting with others, such as parent, partner, sibling, employee, or employer.

Figure 1.16. Families are made up of individuals who share some aspects of identity but also have separate identities of their own.

The social identity wheel in Figure 1.17 includes some common categories for social characteristics in the middle oval. When it comes to social identity, each of us gets to determine our own. That means we determine which of our social characteristics, roles, and group memberships are most important to our own identities. While each of us gets to determine our own social identity, it is important to note that others may identify us differently than we identify ourselves. Our most notable physical aspects may signal something different than our personal lived experience.

Figure 1.17. This social identity wheel includes three kinds of identities: individual characteristics, social characteristics or social identities, and roles and relationships. Image description.

For example, in this video about cultural humility (which will be defined and discussed in the next section), Dr. Melanie Tervalon describes her identity as an African American woman, the difference between how she sees herself and how others see her, and the right that each of us has to our own social identity (Figure 1.18).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=16dSeyLSOKw

Figure 1.18. Cultural Humility Edited [YouTube Video]. Cultural humility involves listening to others about how they define themselves and what their experiences have been.

The multiracial founders of Mixed in America (MIA), Jazmine Jarvis and Meagan Kimberly Smith, have a mission to empower the Mixed community and heal Mixed identities. Take a few minutes to read the first two paragraphs on their webpage here. This is what they had to say about the expression of social identity on Taylor Nolan’s podcast, Let’s Talk About It: “We wanna put the power back in the person’s hands so that they can express in a way that makes them feel authentic” (Nolan, 2020).

According to the social identity theory formulated by Henri Tajfel, we see people who are members of different groups as “others” (McLeod, 2019). In general, we tend to be drawn to those more similar to ourselves, whether by appearance or related to other social characteristics, such as age, ability, or sex. This—in combination with the likelihood of overestimating the similarities within groups and the differences between groups—contributes to socially constructed differences, which we will discuss next.

The Social Construction of Difference

Social identities can help us understand the social construction of difference, which is when hierarchical value is assigned to perceived differences between socially constructed ideas such as race, class, age, ability, or sex (Johnson, 2006). We will extend this concept to include the social construction of difference among families. Via the socially constructed idea of family, American systems and structures regularly create and reinforce inequities among American families.

As we study families, we must keep in mind that this idea of the typical family is not representative of all families, yet it is continually reinforced by the social processes and institutions in our society. Whether you consume big-budget films, social media content, video games, or books and magazines, take a look at what’s in front of you. What kind of people and families do you see represented? While representation of women, people of color, and people of differing sexualities and gender expressions has increased in media, they still mostly play less consequential characters within the plotlines.

Although the majority of families in the United States no longer fit the traditional model (Pew Research Center, 2015), social institutions perpetuate the idea of a certain family structure. Government, schools, medical institutions, businesses, and places of worship all reinforce a typical view of family through the forms, activities, requirements, and processes that are shared with the public. How many times have you tried to fill out a form with checkboxes only to find that you did not “fit” into one of the boxes? Typical examples include giving parental choices of “mother” and “father,” couple status choices such as “married” or “single,” and gender choices such as “male” or “female”—all of which reinforce a binary view of individuals and families.

This results in there being less social support for families who don’t fit this binary—for example, single-parent families; LGBTQ+ families; rural families; or families with a member who is disabled, unemployed, or who has a criminal record. Accepted practices such as “Daddy-Daughter Dances,” churches that exclude or condemn LGBTQ+ ministers or members, the lack of safe housing for low-income families, and educational materials that cannot be read with low vision are all examples of ways that individuals and families are less recognized and less privileged. You can probably think of other examples from your own family’s perspective. Socially constructed differences contribute to many family forms being differentiated as less recognized and valued.

The Social Construction of Race

The social construction of race deserves a special mention, since there is a broadly held public assumption that there are significant biological and genetic differences between human beings based on “race” (meaning observable physical differences such as skin color). In actuality, race is a social construct rather than a biological reality (Figure 1.19).

Figure 1.19. Observable physical differences such as skin color are not equivalent to race.

Scientists state that while genetic diversity exists, it does not divide along the racial lines that many humans notice (Gannon, 2016). In fact, members of the human “race” (all humans) share 99.9 % of their genes (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2011). Ancestry and geography likely influence which genes get “turned on” and expressed. What makes our understanding of race complicated is that we have behaved for centuries as if there is a biological difference. Because there has been a longstanding discriminatory practice against people of color, there are multiple impacts today (Berger & Luckman, 1966). The science arguing against the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construction: a concept that has no objective reality but rather is what people decide it is.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems of placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. Would you consider former President Obama White, Black, or multiracial (Figure 1.20)? He had one Black parent and one White parent. As another example, the well-known golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s, but in fact his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter White, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Williams-León & Nakashima, 2001).

Figure 1.20. Although his ancestry is equally Black and White, Obama considers himself African American. In several Latin American nations, however, Obama would be considered White because of his White ancestry.

Attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of the enslaved lightened over the years as babies were born from the rape of enslaved people by enslavers and other White people. Each state enacted its own definition of being “Black,” and the majority of multiracial people were assigned this designation in order to keep more people enslaved.

Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Records in the early 1980s to change her official race to White. Phipps was descended from an enslaver and an enslaved person and thereafter had only White ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “Black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as Black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 Black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was Black). Phipps had always thought of herself as White and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially Black because she had one Black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 2015).

Social Construction of Other Social Identities, Including Gender

The social construction of gender is another widely accepted concept. In other words, the differences that we attribute to the biological designations of female, male, or intersex are actually predominantly constructed by our societal beliefs and not by biology. The ongoing broadening of gender identity and expression clearly demonstrates this concept.

Other identities are also constructed via societal agreement. Sexuality, ability, religion, ethnicity, age, and other identities may contain some physical parameters as well as personal meaning to the individuals that possess them. Critical to our study of families, however, is the understanding that society creates and reinforces social constructions of these characteristics, and those constructions favor some groups, discriminate against others, and generally impact the lives of families.

Intersectionality

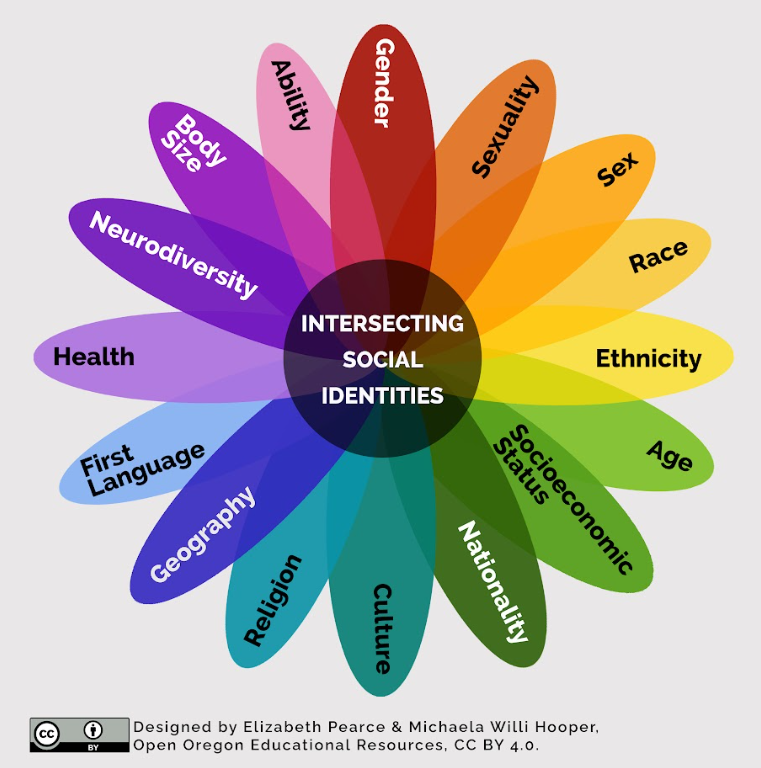

Articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991), the concept of intersectionality identifies a mode of analysis integral to women, gender, and sexuality studies (Figure 1.21). Within intersectional frameworks, race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously, and the meanings of different aspects of identity are shaped by one another. For instance, notions of gender and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others are always impacted by notions of race and the way that person’s race is interpreted.

Notions of Blackness, brownness, and Whiteness always influence gendered experience; there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race. In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability; likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.

Figure 1.21. An idea expressed by many women of color, intersectionality was defined and articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking (Figure 1.22). An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models that presume one aspect of identity (say, gender) dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power.

Figure 1.22. An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social identities of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. Image description.

An example of this idea is the concept of “global sisterhood,” or the idea that all women across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs (Morgan, 2016). If women in different locations did share common interests, it would make sense for them to unite on the basis of gender to fight for social changes on a global scale. Unfortunately, if the analysis stops at gender, what is missed is an attention to how race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some women’s needs in conflict with other women’s needs.This approach obscures the fact that women in different social and geographic locations face different problems.

Many White, middle-class women activists of the mid-20th century United States fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men. But this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class White women, who had already been actively participating in the U.S. labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and enslaved laborers since early colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market are important. But women of the Global South, in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water; access to adequate health care; and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations.

An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related to each other in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. As opposed to a single-determinant model of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources (such as housing and privilege, respectively).

Licenses and Attributions for Social Identities, Social Constructions, and Families

Open Content, Original

“Social Construction of Difference” and “Social Construction of Other Social Identities, Including Gender” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.17. “Social Identity Wheel” by Liz Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.16. Photograph by Jonathan Borba. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 1.19. Photograph by Clay Banks. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 1.20. “Barack Obama on the Primary” by Steve Jurvetson. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 1.21. “Kimberlé Crenshaw” by Mohamed Badarne. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.22. “Intersectionality Wheel” by Liz Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Social Construction of Race” is adapted from “The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: rewritten for clarity.

“Intersectionality” is adapted from Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, and Laura Heston, UMass Amherst Libraries. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: switched images; lightly edited.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.18. “Cultural Humility Edited” © W.B. Jordan. License Terms: Standard YouTube License.

References

Berger, P. L. & Luckman, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. Penguin Books.

Gannon, M. (2016, February 5). Race is a social construct, scientists argue. Scientific American, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/race-is-a-social-construct-scientists-argue/

Omi, M., & Winant, H. (2015). Racial formation in the United States (Third edition). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

McLeod, S. (2019). Social identity theory. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/social-identity-theory.html.

Morgan, R. (2016). Sisterhood is global: The international women’s movement anthology. Open Road Media.

National Human Genome Research Institute. (2011, July 15). Whole Genome Association Studies. https://www.genome.gov/17516714/2006-release-about-whole-genome-association-studies

Nolan, T. (2020). Being Biracial (episode 133). Let’s talk about it with Taylor Nolan. https://letstalkaboutitwithtaylornolan.libsyn.com/

Williams-León, T., & Nakashima, C. L. (Eds.). (2001). The sum of our parts: Mixed-heritage Asian Americans. Temple University Press.