3.4 Love and Union Formation

“Being deeply loved by someone gives you strength, while loving someone deeply gives you courage.”

—Lao Tzu, philosopher

Relationships represent the excitement, passion, security, and connection we experience; they also represent the sadness, heartbreak, insecurities, violence, and loneliness we find at times.

Close relationships, such as those with a confidant or spouse, are highly associated with health and recovery from disease. In studies of various forms of cancer, including breast cancer, having one or more confidants decreased the likelihood and frequency of relapse (Maunsell et al., 1995). As a social species, intimate relationships—those that are characterized by mutual trust, caring, and acceptance and often extend to a romantic or sexual relationship—are a fundamental aspect of our lives (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. People show love and affection through a variety of activities and experiences.

Theories of Love

Love is a multidimensional concept, and psychologists and sociologists have defined it in a variety of ways over the years. One theory identifies six core components of love that are contained in each of our relationships (Lee, 1973). They are:

- Eros: the love of sensuality (taste, touch, sight, hearing, and smell)

- Storgé: the love of your best friend

- Pragma: the love of details and qualities in the other person

- Agapé: the love that is selfless, other-focused, and seeks to serve others rather than receive from others (in Christian theology, it’s the love of God for mankind)

- Ludis: an immature love that is more of a tease than a legitimate loving relationship

- Mania: an insecure love that is a mixture of conflict and artificially romantic eros expressions

Figure 3.6.. This expression of love is one that appears publicly, but has particular personal meaning to the creator and receiver.

In modern-day applications of love, various components make up the ingredients of love: commitment, passion, friendship, trust, loyalty, affection, intimacy, acceptance, caring, concern, care, selflessness, infatuation, and romance. In addition, unconditional love is sincere love that does not vary regardless of the actions of the person who is loved, often related to parenting or kinship relationships. Feelings of love are expressed outwardly and internally as shown in Figure 3.6.

The love types and patterns listed below are taken from many sources but fit neatly into several theoretical paradigms:

- Romance: a love that is based on continual courtship and physical intimacy

- Infatuation: a temporary state of love where the other person is overly idolized and seen in narrow and extremely positive terms

- Commitment: a love that is loyal and devoted

- Altruism: a selfless type of love that serves others while not serving the one who is altruistic

- Passion: sexual or passionate love focused on the intense pleasures of the senses (taste, touch, sight, hearing, and smell)

- Friendship: a love that includes intimacy and trust among close friends

- Realistic love: feelings you have when your list of ideal personal traits in a potential mate is met in the other person

- Obsession: an unhealthy love type where conflict and dramatic extremes in the relationship are both the goal and the theme of the love

Influences on Union Formations

The factors related to the selection of the people that we are emotionally and/or physically intimate with are complex and nuanced. The spirit of this textbook is to aspire to discuss this topic in a way that recognizes the diversity of family formations in the United States. Here we will do our best to identify some of the shared factors that affect human beings who choose a mate for a long-term relationship.

In order to organize our own thinking, we name and label things to better understand the world around us. As our society changes and expands, descriptions and labels come more slowly, creating cultural lag and causing disconnection. For example, marriage was once defined between only a man and a woman. It is now recognized legally that this is a limiting description that is not representative of our nation’s unions. In addition, couples have formed via common-law marriage and/or cohabitation throughout our country’s history. We will use the terms union formations to include all intimate relationships, including marriage. When specific research has focused only on married relationships rather than the broader spectrum, we will use the term “marriage.” Within our text, we acknowledge and celebrate all marriages, unions, partnerships, and relationships that may have mixed legal, religious, or community acceptance. Expressions of affection do not need to be labeled as friendship, love, or marriage; they may be shown in multiple places and ways, as shown by the group of people lounging and hugging each other in Figure 3.7.

We will explore the ways that kinship groups and society influence our selection of a primary mate or mates. In addition, we will review the social exchange theory.

Figure 3.7. Love, comfort, and affection can be shared among two or more people.

Family Experiences, Values, and Expectations

How we choose the people we connect with is influenced by our family experiences, values, and expectations. It is common for adults to communicate and model these with their young children. For example, a parent makes a lighthearted comment about their three-year-old having a boyfriend or girlfriend. And in another comment about marriage, the parent assumes that that child will marry and that it will be to a person of the opposite gender in a binary system. Within the rules and structure of our family of origin, children navigate crucial social experiences that will affect mate selection and relationship dynamics. Young children are most influenced by the world that is both tangible and current. Socialization theory suggests that many of our ideas about gender-based behaviors are formed for life during our early childhood years. Our family of origin impacts how we orient ourselves to particular family themes, identity images, and myths that further identify who is an appropriate intimate partner for us (Anderson & Sabatelli, 2011).

Assortative Mating

When you consider your current mate, or any intimate partners that you seek, are they more like you or quite different from you? The idea of assortative mating, simply put, is that human beings tend to choose intimate mates who are more like themselves than if mates were assigned randomly.

The ways in which we might choose partners assortatively are quite wide and varied but can be divided very loosely into two categories: the physical and the social. Height and appearance both fit into the physical category; in this text, we will focus more on the social categories, which include culture, ethnicity, religion, education, and socioeconomic status (Schwartz, 2013). In particular, education level has become an increasingly assortative factor within union formations in the United States. Between the 1940s and the 1980s, education increased as an assortative factor until it leveled off for those with higher education degrees. It continues to increase for those without a high school degree, however (Eika et al., 2017). While the patterns in assortative and disassortative relationships have been studied, it is challenging to determine the underlying reasons for this behavior.

Because income level is increasingly associated with higher education, this pattern interacts with the trends in socioeconomic status in the United States and may contribute to the cycle of poverty. It is important to note that this change affects the current generations in ways that we don’t yet completely understand. Millennials and Gen Z are coping with the increased importance of education to income and status at the same time that college costs and student debt have increased dramatically. How this affects union formation and other family patterns remains to be seen. Based on what is known about couples wanting to be financially stable before marrying, it is likely that the trend of marrying less and marrying later will continue.

Economics and Social Movements

Economics and social change affect personal choices about unions, but they also influence the way the role of mate, partner, or spouse is defined. In the early days of this country, and indeed before the formation of the United States, both Indigenous families and Euro-American settlers relied on their kinship and family groupings for survival. Indigenous families lived in tribes that shared spiritual beliefs and resources. Extended kin networks were, and still are, critical to the stability of the community (Deer et al., 2008). Euro-American families were large, with an emphasis on mate selection that would ensure not only survival but also relative financial stability. Fertility was valued because children were seen as assets in the shared family work. Love as a rationale for marriage was disdained; feelings might change, and a marriage built on instability could threaten survival (Coontz, 2000).

Figure 3.8. Industrialization and other economic changes influence union formations and patterns.

As the country industrialized, as shown in Figure 3.8, roles became more gender specific: men tended to work in the factories, and women more likely managed the home and children. As you saw in Chapter 1, this is known as the development of separate spheres, an idea that has persisted, albeit in a weakened state, into the 21st century (Lewis, 2019). A growing economy and more routinized family patterns contributed to stability and a decreased focus on survival. It was still important to consider economics in a partnership, but romance, sexual companionship, and love also became expectations of intimate and marriage relationships. Family size decreased dramatically as both child mortality decreased and the White middle class evolved.

However, this progress was enabled by the less privileged.Children and women in minoritized groups continued to contribute to the family income. Labor laws protected most White children. For example, social programs such as the Social Security Act of 1935 excluded domestic and agricultural workers, who were primarily immigrants and people of color. It is important to note that the idealized version of a sparkling house, home-cooked meals, and wife and mother who volunteered at her child’s school was maintained via the assistance of other low-paid workers in the home, usually members of minoritized groups. In families that were not protected and privileged by government programs, survival was and is still paramount.

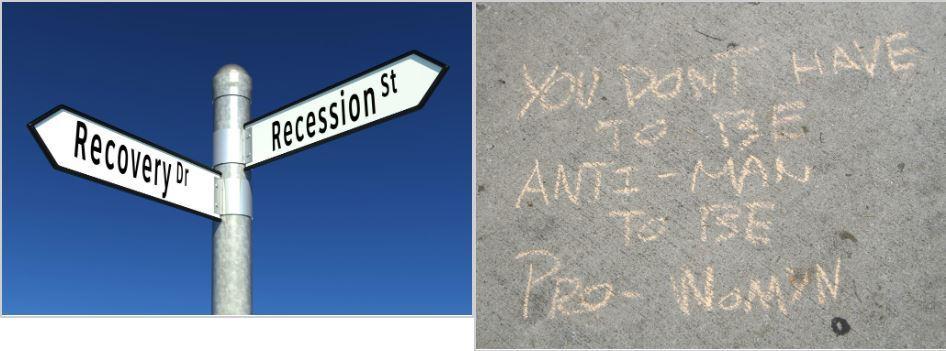

Figure 3.9. Economic changes along with social movements have a surprising effect on relationships, union formations, and breakups.

The economy in the United States had steadily improved over centuries, but between the 1970s and the present, the country has experienced increasing numbers of shorter periods of both stability and recession. Social movements and technological changes in the same time frame have contributed to a structural and social broadening of the definition of the role of a partner. Figure 3.9 illustrates economic and social changes that influence union formations.The feminist, civil rights, and LGBTQ+ movements have all influenced the ways in which individuals define themselves and therefore how we select mates. Interracial and same-sex couplings had existed long before they were openly discussed and eventually legalized. But it is clear that legal and social acceptance has increased the visibility and likely the number of these relationships as well. The public changes in acceptance of interracial or same-sex relationships are important to note when it comes to the earlier discussion of assortative matings.

Technological advances such as the automobile, household appliances, and the computer all influence relationships. The car makes it more possible for people to meet up and have privacy, and household appliances increase the available time for other parts of life, including partner, friend, and family relationships. Computers, the internet, and phones all facilitate communication and connection in a variety of ways.

Changing Expectations

The United States is an individualistic country, and at the same time that we have seen increased social movements, we have also seen an increase in individualism that must affect our most intimate relationships. While we continue to see marriage as an economic partnership, as well as a source of romance, sex, and companionship, there is now an additional expectation—the importance of self-fulfillment and personal happiness. This adds even more pressure to the mating partnership and may contribute to the decrease in stability and length of marriages (Finkel et al., 2014).

The social exchange theory, as described in Chapter 2, is also applicable here. A person might be attracted to someone based on their first impressions—for instance, “They’re cute and have a sense of humor that matches mine.” After observing them longer, someone might say, “But they also avoid doing their work in class group projects.” The social exchange theory says that we evaluate relationships based on looking at the person’s advantages and disadvantages to decide if we would want to enter a relationship with them. And what do we have to offer in exchange (our own goods and costs)? This theory emphasizes the implicit agreements that couples exchange when they enter a relationship.

We have been socialized to think of the married White middle-class nuclear family living the “American Dream” as the ideal representation of family within the United States, represented by Figure 3.10. This socially constructed ideal has been based on heterosexual norms. This is something that should not be quickly disregarded, as it has shaped and influenced people’s thinking, whether or not they personally believe in these ideals.

Figure 3.10. Today’s couples use both traditional symbols and postmodern choices in their weddings.

U.S. families are as diverse as the people who live here. It is important to understand that as a nation, we have many similarities in regards to our experiences, values, and expectations. We also have differences. We describe here some of the institutional forces and theoretical ideas about how individuals enter into amorous relationships, but we also acknowledge that each relationship is unique, complex, and nuanced in ways that are indescribable in writing.

Licenses and Attributions for Love and Union Formation

Open Content, Original

“Influences on Union Formation” by Nyssa Cronin and Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Family Experiences, Values, and Expectionas” by Nyssa Cronin and Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Assortative Mating” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Nyssa Cronin. License: CC BY 4.0.

“The Evolving Economy” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Social Constructions and Theories that Impact Relationships” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Theories of Love” is adapted from Health Education by Garrett Rieck and Justin Lundin. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Nyssa Cronin: edited for brevity; terms replaced.

Figure 3.5. “Must be love” by dr. zaro. License: CC BY-NC 2.0, “Couple” by Gaulsstin. License: CC BY-NC 2.0, Photo by Zackary Drucker / The Gender Spectrum Collection. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 3.6. “Love” by Hc_07. License: CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 3.7. “Fall Asleep” by LordKhan. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 3.8. Photograph by Patrick Hendry. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 3.9. “3D Recession Recovery” by ccPixs.com. License: CC BY 2.0. “Take Back the Night 2010” by Marcus Johnstone. License: CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 3.10. Photograph by Євгенія Височина. License: Unsplash License.

References

Anderson, S. A., & Sabatelli, R. M. (2011). Family interaction: A multigenerational developmental perspective (5th ed). Allyn & Bacon.

Coontz, S. (2000). Historical perspectives on family studies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00283.x

Deer, S., Clairmont, B., & Martell, C. A. (Eds.). (2008). Sharing our stories of survival: Native women surviving violence. AltaMira Press.

Eika, L., Mogstad, M., & Zafar, B. (2017, March). Educational assortative mating and household income. Federal Reserve Bank of New York. https://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/media/research/staff_reports/sr682.pdf

Finkel, E. J., Hui, C. M., Carswell, K. L., & Larson, G. M. (2014). The suffocation of marriage: Climbing mount maslow without enough oxygen. Psychological Inquiry, 25(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.863723

Lee, J. (1973). Colours of Love: An Exploration of the Ways of Loving. New Press.

Lewis, J. J. (2019, September 11). Separate spheres for men and women. ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/separate-spheres-ideology-3529523

Maunsell, E., Brisson, J., & Deschênes, L. (1995). Social support and survival among women with breast cancer. Cancer, 76(4), 631–637. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950815)76:4<631::aid-cncr2820760414>3.0.co;2-9.

Schwartz, C. R. (2013). Trends and Variation in Assortative Mating: Causes and Consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 39(1), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1146%2Fannurev-soc-071312-145544