5.4 Culture and Families

As discussed in Chapter 2, culture, broadly defined, is the set of beliefs, values, symbols, means of communication, religion, logics, rituals, fashions, etiquette, foods, and art that unite a particular society. Culture elements are learned behaviors; children learn them while growing up in a particular culture as older members teach them how to live. As such, culture is passed down from one generation to the next.

Culture is intertwined with both ethnicity, religion, and spirituality. Ethnicity refers to the shared social, cultural, and historical experiences, stemming from common national, ancestral, or regional backgrounds, that make subgroups of a population different from one another. Similarly, an ethnic group is a subgroup of a population with a set of shared social, cultural, and historical experiences; relatively distinctive beliefs, values, and behaviors; and some sense of identity or belonging to the subgroup. Pan-ethnicity is the grouping together of multiple ethnicities and nationalities under a single label. For example, people in the United States with Vietnamese, Cambodian, Japanese, and Korean backgrounds could be grouped together under the pan-ethnic label Asian American. The United States has five pan-ethnic groups, including Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, European Americans, and Latinos. The grouping together of multiple ethnicities or nationalities under one umbrella term can be helpful, but it can also be problematic—these groups may share geography, but they have differing values, beliefs, and rituals.

In addition to ethnicity, other terms are used to refer to this aspect of cultures, such as majority and minoritized or marginalized cultures, or dominant and nondominant cultures or macro- and microcultures. Some groups relate to the social identities based on regions (the South, the East Coast, urban, rural) or affiliation (street gangs, NASCAR fans, college students). Such groups are not necessarily distinct cultures but rather groups of people who share concerns and who might perceive similarities due to common interests or characteristics (Lustig & Koester, 2010).

Religion is a collection of cultural systems, belief systems, and worldviews that relate humanity to spirituality and, sometimes, to moral values. Many religions have narratives, symbols, traditions, and sacred histories that are intended to give meaning to life or to explain the origin of life or the universe. People may affiliate with religions, beliefs, or a general sense of spirituality.

In Focus: What Brings Us Together

Elizabeth Torres

My whole family has such a close relationship and tight bond because we do a lot as a group, including working together. I would say that our religion and culture does play a big role in this.

Figure 5.7. Both food and religion can bring a sense of belonging in a family’s culture.

In our culture, food is a big thing, and we always work together to cook for the family. We are also always willing to help one another whenever one needs a hand, and that’s where religion comes in. Being Catholic, we are just always taught to be nice and respectful toward everyone, especially your family.

Families maintain traditions, rituals, and routines that are heavily influenced by the cultural spaces that any kinship group occupies. But families are also made up of individuals, and while a kinship group may share a culture, individuals may embrace different cultures, ethnic identities, and religious or spiritual beliefs, which creates complexities in family life.

For example, for immigrant and refugee families in the United States, religiosity can be a protective factor when adapting to another culture. Religiosity and spirituality, often integrated with one’s ethnic identity, rituals, and traditions, appear to play a significant role as protective factors in the immigrant paradox among Latino and Somali youth (Areba, 2015; Ruiz & Steffen, 2011). What happens when individuals within a family have differing beliefs? People who grew up in families where parents had different religions from one another report less overall religiosity (McPhail, 2019). Children may grow up with differing religious or spiritual beliefs than what their parents have. Especially in the case of children who identify as LGBTQIA+ within a family whose religious or moral beliefs negate these identities, children can experience dissonance and a lack of connection within their family.

Belonging

While there are many definitions and conceptualizations of belonging, one definition is when a person experiences a subjective feeling that they are an integral part of their surrounding systems, including their friends, family, school and work environments, communities, cultural groups, and physical places (Hagerty et al., 1992). The need for belonging, “to connect deeply with other people and secure places, to align with one’s cultural and subcultural identities, and to feel like one is a part of the systems around them,” is a very basic human need (Allen et al., 2021). Connection with others, physical safety, and well-being are inextricably linked and are crucial for survival (Boyd & Richardson, 2009). A greater sense of belonging is associated with positive psychosocial outcomes.

The benefits and potential protective factors derived from a sense of belonging are especially potent for individuals who identify with marginalized or minoritized groups, including people who identify as sexually or gender diverse, people with disabilities, or those who experience mental health issues (Gardner et al., 2019; Harrist & Bradley, 2002; Rainey et al., 2018; Spencer et al., 2016; Steger & Kashdan, 2009). Among college students from minoritized communities, social belonging interventions are associated with positive impacts on academic and health outcomes (Walton & Cohen, 2011). Other positive effects include having a healthy sense of belonging, including more positive social relationships, academic achievement, occupational success, and better physical and mental health (Allen et al., 2018; Goodenow & Grady, 1993; Hagerty et al., 1992).

In contrast to the benefits of feeling a sense of belonging, a lack of belonging has been linked to an increased risk for mental and physical health problems (Cacioppo et al., 2015). The health risks associated with social isolation can be the equivalent to smoking 15 cigarettes a day and are twice as harmful as obesity (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2015). Social isolation across the lifespan is associated with poor sleep quality, depression, cardiovascular difficulties, rapid cognitive decline, reduced immunity, increased risk for mental illness, lowered immune functioning, antisocial behavior, physical illness, and early mortality (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2003; Cacioppo et al., 2011; Choenarom et al., 2005; Cornwell & Waite, 2009; Hawkley & Capitanio, 2015; Holt-Lunstad, 2018; Leary, 1990; Slavich et al., 2010; O’Donovan et al., 2010).

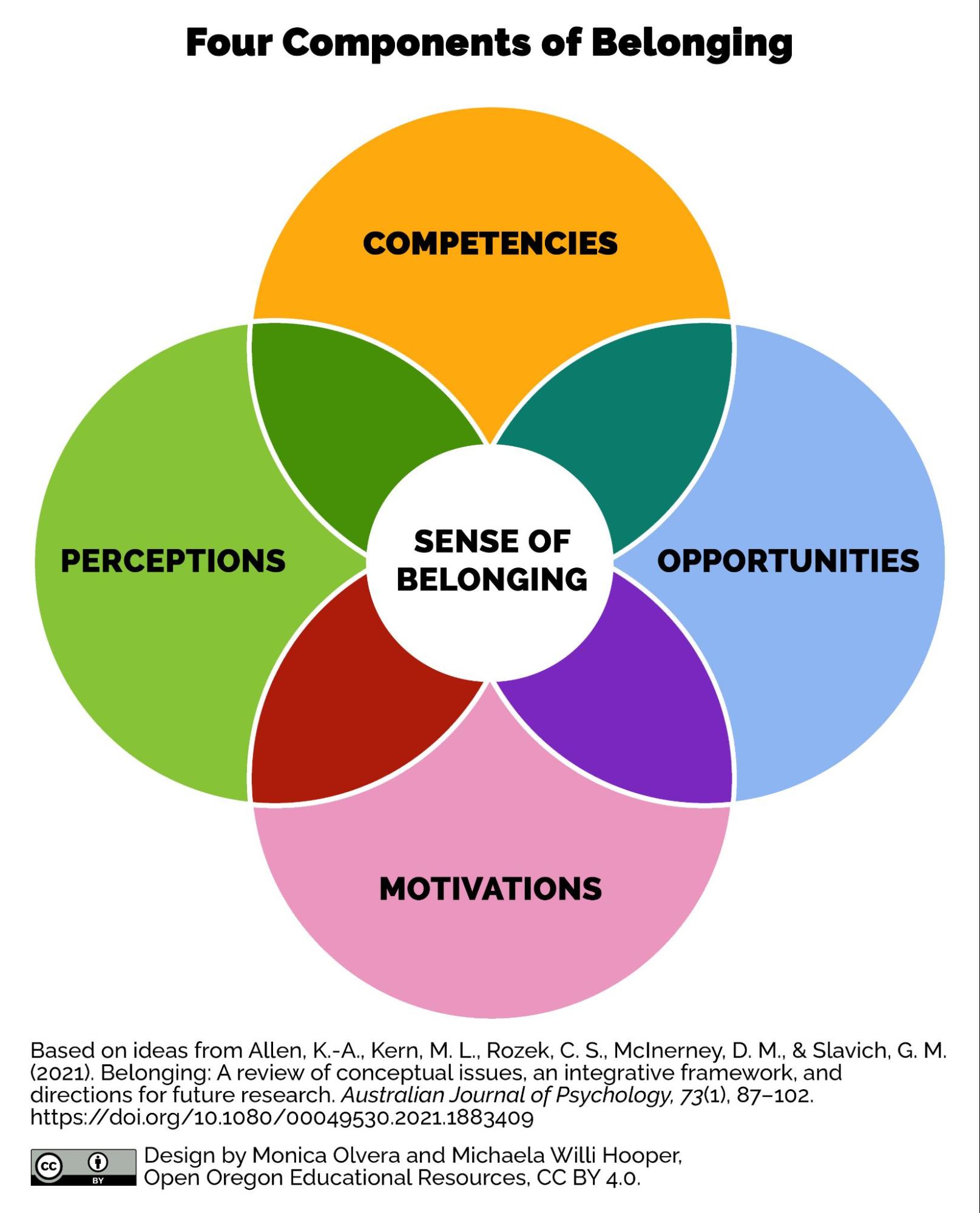

Belonging can be fostered at the individual and social level. Figure 5.8 provides a framework for understanding and fostering belonging. A sense of belonging can be impacted by one’s competencies, opportunities, perceptions, and motivations (Allen et al., 2021).

Figure 5.8. This graphic shows an integrated framework for understanding, assessing, and fostering belonging (adapted from Allen et al., 2021). Image description.

Competency refers to having a set of skills and abilities that are needed to connect and relate to others, develop a sense of identity, and ensure one’s behavior aligns with social norms and cultural values.

Opportunities to belong come from the availability of groups, people, places, times, and spaces to connect with others in ways that allow belonging to occur. Individuals from isolated or rural areas, first- and second-generation immigrants, and refugees may experience circumstances that limit opportunities to foster belonging. The lack of opportunities for belonging was sharply felt during the COVID-19 pandemic, when shelter-in-place orders and social distancing measures limited human interactions. But despite opportunities to connect in person, technologies such as gaming and social media quickly became more favored opportunities for connection, especially for youth, those who are shy, or people who experience social anxiety (Allen et al., 2014; Amichai-Hamburger et al., 2002; Davis, 2012; Moore & McElroy, 2012; Seabrook et al., 2016; Seidman, 2013).

Motivations to belong consist of the need or desire to connect with others or the fundamental need to feel accepted, belong, and seek social interactions and connections (Leary & Kelly, 2009).

Individuals have varying perceptions of belonging within their kinship groups and within chosen or assigned cultures. Perceptions of belonging are related to one’s subjective feelings and cognitions regarding their experiences and are informed by past experiences. A person’s negative perceptions of self or others, stereotypes, and negative experiences such as feeling left out can affect the desire to connect with others.

Cultural Erasure and Cultural Persistence

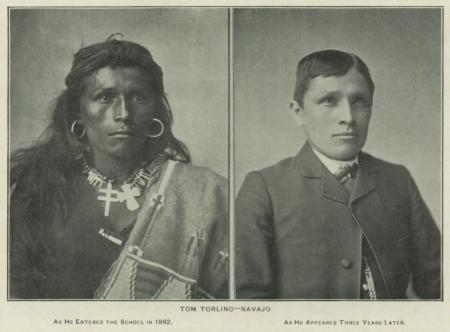

Cultural erasure is the practice of a dominant culture contributing to the erasure of a non-dominant or minoritized culture. An example of active cultural erasure would be that of Native American children being forced to attend residential boarding schools, where they might be punished for speaking their heritage language, forced to wear uniforms that were stripped of makers of their their community and identity, and harshly mistreated, even to the point of starvation or being beaten (Figure 5.9). The strategy of not allowing the children to speak their communities’ languages or learn and practice their communities’ traditions and rituals was active cultural erasure. Passive cultural erasure could include the histories of communities not being included in historical textbooks or the passing of laws that prohibit people from wearing jewelry, hair styles, clothing, or other items that are indicators of one’s cultural identity.

Figure 5.9. The photographs here show “before” and “after” portraits of a student at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, a residential boarding school built on the idea that education should “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Cultural persistence, then, is the very opposite of cultural erasure. Cultural persistence is when elements of culture (such as language, rituals, foodways, and traditions) persist despite efforts to blot out those cultural practices and identities. Among Black Caribbean immigrants, gatherings of family and friends called “liming” sessions reinforce family and cultural identities through storytelling (Brooks, 2013). Another example of cultural persistence is that of language revitalization programs among Indigenous communities, such as the Chinuk Wawa language program supported by Lane Community College (LCC) in Eugene, Oregon. This program consists of a collaboration between Lane Community College, the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, and the Northwest Indian Language Institute of the University of Oregon (UO). This program, which has operated for nearly a decade, provides language classes for tribal members, LCC and UO students, and members of the Grand Ronde Community.

Licenses and Attributions for Culture and Families

Open Content, Original

“Culture and Families” and all subsections except those noted below by Monica Olvera. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: What Brings Us Together” By Elizabeth Torres. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 5.8 “Four Components of Belonging” designed by Monica Olvera and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0. Based on ideas from “Belonging: A Review of Conceptual Issues, an Integrative Framework, and Directions for Future Research” by K.-A. Allen, M. L. Kern, C. S. Rozek, D. M. McInerney, & G. M. Slavich in Australian Journal of Psychology.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Culture” by Libre Texts. License: CC BY-SA.

“Ethnicity and Religion” by Libre Texts. License: CC BY-NC-SA.

“The Nature of Religion” by Libre Texts. License: CC BY-SA.

Figure 5.7 “Photo“ by Jeswin Thomas on unsplash.com. License: Unsplash License.

Figure 5.9 “Tom Torlino – Navajo” by Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center. License: CC BY-NC-SA.

References

Brooks, L. J. (2013). The Black survivors: Courage, strength, creativity and resilience in the cultural traditions of Black Caribbean immigrants. In J.D. Sinnott (Ed.) Positive Psychology (pp. 121-134). New York: Springer.

Lustig, M., & Koester, J. (2010). Intercultural communication: interpersonal communication across cultures. J. Koester.–Boston: Pearson Education.

What Census Calls Us. (2020, May 30). Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/what-census-calls-us/