5.5 Cultural Identities

There are many aspects to our identities, such as our family histories, religious affiliation, and nationality. A major component of our identities can be our ethnicity and cultural heritage. In this section, we will consider various aspects of ethnic identity and how it can change over time.

Positive Ethnic Identity Model

Researcher Jean S. Phinney defines ethnic identity as a sense of self that is derived from a sense of belonging to a group, a culture, and a particular setting. Aspects of ethnic identity can also include a person’s knowledge of an ethnic group they identify with and how valuable or significant it is to be a member of an ethnic group (Tajfel, 1981). Ethnic identity is a multidimensional construct that can change over time and context (Phinney, 2003). Ethnic identity can be developed and reinforced by engaging in activities associated with one’s culture or ethnic group, such as associating with members of one’s group or speaking a shared language. But ethnic identity can also exist as an internal structure, independent of such behaviors (Phinney & Ong, 2007).

Components of ethnic identity also include in-group attitudes toward one’s own ethnic group, as well toward other groups:

- Positive ethnic identity: a positive self-attitude derived from a sense of belonging to groups that are meaningful to a person (Phinney, 1989; Tajfel & Turner, 1986).

- Intragroup affinity: a positive or affirming sense of one’s own ethnic identity that creates a sense of pride in one’s ethnic identity. Possessing intragroup affinity has been linked to reduced depressive symptoms among youth from minoritized communities (Smith & Silva, 2011) and is associated with positive

- Intergroup affinity: positive attitudes toward ethnic groups other than a group where an individual has ascribed membership. Intergroup affinity has been linked to reduction of intergroup conflict among youth from minoritized ethnic groups (Phinney & Ferguson, 1997).

Acculturation Model

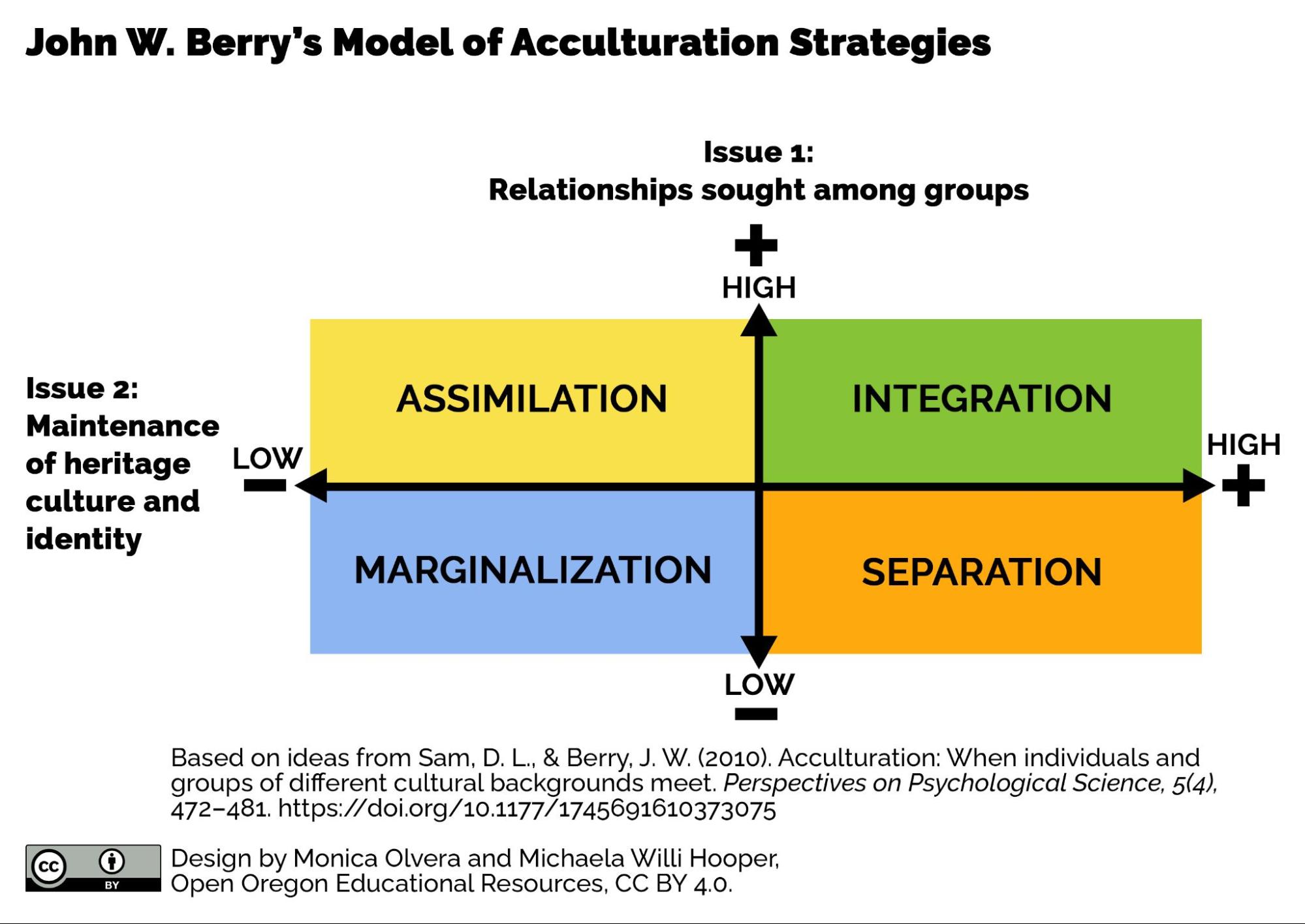

Our lives are increasingly defined by technology and globalization that allows us to interact with people on the other side of the world, as well as learn about and internalize components of many cultures. When individuals and families are exposed to new cultures, they go through a process of acculturation, or adapting to a new culture (Berry, 2003). Figure 5.10 shows a model of acculturation proposed by John Berry (1980), who anticipated that acculturating individuals face two issues: 1) the dominant culture orientation, or the extent to which acculturating individuals are involved with the receiving or host culture, and 2) the heritage cultural orientation, or the extent to which individuals are involved with their heritage, ethnic, or nondominant culture (Nguyen & Benet-Martínez, 2013).

Figure 5.10. This chart shows John W. Berry’s model of acculturation strategies. Image description.

One helpful framework to understand acculturation is a model developed by psychologist John W. Berry. His model examines four acculturation strategies: assimilation, integration, separation, and marginalization (Berry, 2003).

Assimilation strategy is utilized when an individual does not seek to maintain their cultural identity and instead pursues close interaction with other cultures. The person may adopt the cultural norms, values, and traditions of the new society.

Integration strategy is utilized by those who wish to maintain one’s original culture as a member of an ethnocultural group. At the same time, they may also participate as a member of the dominant society. In this way, the person both maintains aspects of their original culture while also incorporating aspects of a newer culture into their cultural knowledge and practices. This strategy has been found to be the most adaptive, and it is linked to better psychological and sociocultural adaptation (Liebkind, 2001; Sam et al., 2008).

The separation strategy is chosen by those who place a high value on maintaining the integrity of their original cultural identity and avoid interaction with those of the new society. The marginalization strategy consists of placing a low value on cultural maintenance and also avoiding interactions with those of the new society, sometimes due to experiences of exclusion or discrimination. This strategy has been found to be the least adaptive.

A person may utilize different strategies, depending on context and circumstances, as the strategies are not static. The attitudes of the larger society toward the immigrants and the types of settlement policies the larger society places on acculturating groups can influence which strategy gets adopted. Generally, integration is the preferred strategy for optimal outcomes, whereas marginalization is the least preferred strategy (Berry, 2003).

In contrast to acculturation, assimilation is a strategy utilized when an individual does not seek to maintain their cultural identity and instead pursues close interaction with other cultures, adopting the cultural norms, values, and traditions of the new society. With respect to policies applied to immigrant communities in the United States, however, assimilation has been a multidimensional process of boundary brokering and reduction in which ethnic distinctions, and the social and cultural differences and identities associated with them, are purposefully blurred or dissolved (Alba & Nee, 2009).

At the group level, “assimilation may involve the absorption of one or more minority groups into the mainstream,” whereas at the individual level, “assimilation denotes the cumulative changes that make individuals of one ethnic group more acculturated, integrated, and identified with the members of another” (Rumbaut, 2015, p. 2). This approach has been used to justify selective, state-imposed policies and practices with the goal of eradicating minoritized cultures and achieving the “benevolent” conquest of other peoples. One striking example is the effort to Americanize, Christianize, and “civilize” Native American children by forcibly removing them from their families and sending them to residential schools, such as the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. Around 270 children died while in custody at the Chemawa Indian School between 1880 and 1945 (Pember, 2021).

In environments that tend toward assimilation, cultural maintenance in ethnic minorities can lead to lower levels of life satisfaction (Kus-Harbord & Ward, 2015). In contrast, policies and practices that allow individuals, families, and groups to create communities of belonging and practice their heritage cultures can promote equity.

Creating Communities of Belonging

Whether a person is a student who moved to a new area to attend college in a community they are unfamiliar with or a person who immigrated to a host country and has yet to get to know the new receiving community, people tend to seek or create community by utilizing anchoring practices. Like an anchor of a boat, meant to keep a boat in a specific place and not be moved by tides, currents, or winds, anchoring practices are the behaviors, efforts, and actions people carry out to seek, create, and maintain a sense of community and rootedness.

When a person, a family, or a group of people move to a new community, there is a human need to create a sense of belonging while experiencing challenges like isolation and loneliness (Campbell, 2008; Narchal, 2012). Families can make use of existing social networks to tap into community groups, or they may have to create entirely new spaces. For example, Somali refugee families in Boston utilized existing religious organizations, family support, and community organizations to tap into existing communities, thus benefiting from peer and family support, religious faith, and social support networks to make new lives for themselves (Betancourt et al., 2014). Connections with family members help immigrants and refugees retain a sense of identity within their culture and family (Lim, 2009). Newly arrived people may connect with family members or friends who are already settled in a community, religious organizations (e.g., mosques or churches), schools, cultural or community centers, and nonprofit organizations aimed at helping immigrant and refugee families (e.g., the Center for African Immigrants and Refugees Organization [CAIRO]).

Anchoring practices could include forming community spaces when those spaces do not already exist. For example, in Corvallis, Oregon, a small group of Mexican immigrant families got together to form a folkloric Mexican dance group so that the children’s positive cultural identity could be encouraged and parents could mutually support each other (Figure 5.11).

The ways immigrant and refugee individuals, families, and communities seek, create, and maintain support vary widely. They may draw on family and community resilience to find ways to continue to survive and, in many cases, thrive.

Figure 5.11. Three dancers perform the folkloric Mexican dance “Los Machetes de Jalisco.”

Cultural Resistance and Persistence

We opened this section with brief definitions and examples of cultural erasure and cultural persistence. Here we will focus more deeply on the ways that communities of belonging work to resist erasure and persist in keeping cultures alive.

Throughout U.S. history, among the many horrific ways Native Americans were treated, one strategy to delegitimize their cultures is paper genocide, or state and federal recognition titles used to determine Native Americans’ significance, presence, and legacy in U.S. history and society or to refute their identity. There are strict criteria for a tribe to be federally recognized, and it can be difficult for some Indigenous communities to “obtain enough tangible historic resources to prove their ancestry or community” (Nguyễn & Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, 2020, p. 5).

The Eastern Pequot Archeology Field School in Connecticut is a clear example of a community outright resisting cultural erasure while building community in a culturally affirming way. As a part of this revival effort, the Eastern Pequot Archaeology Field School provides tangible items from the past that ground the tribal members to their reservation, which has been established for hundreds of years. Items such as arrowheads, musket bullets, and scissors show that the Eastern Pequots’ ancestors lived with their European colonizers from the 17th to the 19th centuries, as their Indigenous presence was enough to resist colonization. Over 99,000 artifacts found throughout the 15 Field School seasons dismantle the common misconception of how Native Americans lived during the beginning of the United States’ history and redefines modern beliefs about how Indigenous peoples survived European colonization. The Field School transforms the brief binary description of Indigenous history into a more complicated and dynamic story that elaborates on Indigenous struggle, survival, and resistance (Nguyễn & Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation, 2020).

In Focus: Reviving the Hawaiian Language

Here we will look at the multigenerational efforts to rescue and revive the Hawaiian language, which has been almost entirely eliminated by Hawai’i’s colonizers in an attempt at cultural erasure.

Before the arrival of Captain Cook in Hawai’i in 1778, Hawaiians had lived and thrived for centuries in the islands, creating a distinct and rich culture, including a plentiful oral tradition. The Hawaiian language, or ‘ōlelo Hawai’i, embodied a cultural history that linked Hawaiians to their history, cosmology, and worldview. Kāhuna (priests) could recite from memory the origin chant, or Kumulipo, which contains over 2,000 lines of text (Beckwith, 1972; Mitchell, 1992). Countless mo‘olelo (stories), ka‘ao (epic legends), mele (songs), and pule (prayers) were vehicles for conveying values, teachings, and histories to the people.

In the 1800s, the arrival of American missionaries prompted profound changes on ‘ōlelo Hawai’i. Missionaries built schools with the intention of using education to convert Hawaiians to Christianity. Hawaiians learned Latin and French in addition to English, with per capita literacy rates at 91% in the late 1800s (Nogelmeier, 2003).

One primary tool the missionaries utilized in their efforts was the printing press. With this technology, books and newspapers written in ‘ōlelo Hawai’i were printed and circulated in the community. One of the first printed books was the Bible. Despite the usage of ‘ōlelo Hawai’i in printed text, however, ‘ōlelo Hawai’i was considered a lower-status language, and instruction in ‘ōlelo Hawai’i was not prioritized.

In the late 1800s, political unrest, foreign influence (including by American investors and businessmen), and the involvement of the U.S. military, culminated in the illegal overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani in 1893. This was followed by the establishment of a provisional government and the American annexation of Hawai’i. The Republic of Hawai’i was established, made up of foreign businessmen and missionary descendents, who viewed ‘ōlelo Hawai’i as a political threat. In June 1896, Act 57 was passed, which declared that only English could be used as the language of instruction in schools. Thus, children would no longer receive instruction in schools in ‘ōlelo Hawai’i. Children were shamed and punished for speaking Hawaiian at school, and the language was stigmatized. This stigma expanded to other areas of Hawaiian society (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007).

From 1898 to 1959, ‘ōlelo Hawai’i was mostly limited to the entertainment sector, while English permeated all other aspects of people’s daily lives, in addition to dealings in business, schools, and government. The only remaining group of people who spoke ‘ōlelo Hawai’i as their native language was a group of kūpuna (elders in their 70s) in a small, isolated community on the island of Ni’ihau (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). In addition, ‘ōlelo Hawai’i was being taught as a foreign language at the University of Hawai’i. By the late 1970s, fewer than 50 children were reported to speak Hawaiian. There was fear that once the kūpuna were gone, the language would also disappear (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). A once-thriving language was at a precarious point.

Elders began strident efforts to revitalize its usage. In 1977, Ka Leo O Hawai’i, a Hawaiian language radio show, aired its first broadcast in ‘ōlelo Hawai’i on KCCN in 1977. Also in 1977, the nonprofit organization ‘Ahahui ‘Ōlelo Hawai’i established standardized Hawaiian written language and conventions. Progress continued as ‘ōlelo Hawai’i was recognized as a state language in 1978, and the 1896 law banning instruction in ‘ōlelo Hawai’i in schools was lifted.

A small group of parents and educators wanted their children to learn ‘ōlelo Hawai’i, but it had not been taught in schools for many decades, and the law that banned the language as a medium of instruction had only recently been lifted.The parents wanted their children to not only speak Hawaiian at home but also be educated through instruction delivered in the Hawaiian language. The parents knew that if ‘ōlelo Hawai’i were to flourish again, it needed to be spoken in various settings (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). Thus, in 1984, the ‘Aha Pūnana Leo Hawaiian language immersion preschool was launched.

The establishment of the family-based language immersion preschool program provided multiple challenges for the teachers and parents in the first years it operated. There were many questions: Where would the curriculum and books come from? Which schools would be willing to allow a Hawaiian language immersion program in their school? Who had a teaching certificate and could speak Hawaiian? How would the program be funded?

The solutions to these questions came from the dedication of the first group of parents and educators, who created a program patterned after the successful efforts of the language and cultural revitalization of the Māori of Aotearoa (New Zealand) in the early 1980s (Kawai‘ae‘a et al., 2007). School staff would translate materials and develop curriculum on a year basis, essentially laying the path for the children as the first cohort of students made their way through the program (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). The preschool program expanded into a preschool through kindergarten and then added first grade, then second grade, and so on. Finally, the program expanded to cover preschool all the way to 12th grade for graduating high school seniors by 1992. In 1999, a cohort of students graduated that, for the first time in over 100 years, had been educated entirely in Hawaiian from kindergarten to grade 12. One parent shared, “As we are frequently met with unsupportive policies, institutional resistance, and supporters of the status quo, we continue to relay our aloha for the language, sharing the potential of and need for Hawaiian language immersion education” (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007, p. 202).

Some critics considered Hawaiian to be a “dead language” and expressed concern for the children’s future, believing the children would not be able to attend college because they did not know English. The opposite was true, however, as the immersion program has a 100% high school graduation rate, and 80% of the graduates pursue higher education at the university level (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). Figure 5.12 shows that common phrases in Hawaiian are used today.

Figure 5.12. Mele Kalikimaka translates as “Merry Christmas” and Hau ‘oli Makahiki Hou as “Happy New Year” in this image from the Honolulu City Lights taken in 2013.

For the educators, parents, and now grandparents of the children who attend ‘ōlelo Hawai’i programs, the revitalization of ‘ōlelo Hawai’i is deeply important. It is the reconnection to their rich cultural heritage, the passing on of cultural wisdom from one generation to another, and a source of traditional knowledge. One parent marveled, “It was amazing to witness the keiki [children] fluently speaking, singing, praying, learning, playing, creating, fighting, and, I would surmise, dreaming, all in Hawaiian”’ (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007). Children who learned in the language immersion program developed proficiency in multiple languages and formed strong cultural and self-identity (Kawai’ae’a et al., 2007).

Parents, grandparents, and educators involved in the language immersion program, as well as the graduates themselves, believe that their legacy is the Hawaiian language that lives on and continues to flourish in their children and grandchildren. Thanks to them, the language and their rich traditions are on the pathway to thrive once again. What is more, the model employed in the development of the language immersion program has provided a model for other language revitalization efforts. In 2008, the ‘Aha Pūnana Leo Hawaiian language immersion preschool celebrated its 25th anniversary.

Licenses and Attributions for Cultural Identities

Open Content, Original

“Cultural Identities” and all subsections except those noted below by Monica Olvera. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.10. “John W. Berry’s Model of Acculturation Strategies” designed by Monica Olvera and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0. Based on ideas from “Acculturation: When Individuals and Groups of Different Cultural Backgrounds Meet” by D. L. Sam and J. W. Berry in Perspectives on Psychological Science.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.11

“Pequot Warriors Combating Paper Genocide: How the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation Uses Education to Resist Cultural Erasure” by L.-H. Nguyễn and Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 5.12. “Honolulu City Lights” by Daniel Ramirez. License: CC BY-2.0 Generic.

References

Alba, R. D., & Nee, V. (2009). Remaking the American mainstream. In Remaking the American mainstream. Harvard University Press.

Allen, Kern, M. L., Vella-Brodrick, D., Hattie, J., & Waters, L. (2018). What Schools Need to Know About Fostering School Belonging: a Meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-016-9389-8

Allen, Kern, M. L., Rozek, C. S., McInerney, D. M., & Slavich, G. M. (2021). Belonging: a review of conceptual issues, an integrative framework, and directions for future research. Australian Journal of Psychology, 73(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2021.1883409

Amichai-Hamburger, Wainapel, G., & Fox, S. (2002). “On the Internet No One Knows I’m an Introvert”: Extroversion, Neuroticism, and Internet Interaction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 5(2), 125–128. https://doi.org/10.1089/109493102753770507

Areba, M. E. (2016). Divine solutions for our youth: a conversation with Imam Hassan Mohamud. Creative Nursing, 22(1), 29–32.

Beckwith, Martha. 1972. The Kumulipo: A Hawaiian creation chant. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai’i Press.

Berry, J. W. (1974). Psychological aspects of cultural pluralism. Culture Learning, 2, 17–22.

Berry, J. W. (1980). Acculturation as varieties of adaptation. In A. M. Padilla (Ed.), Acculturation: Theory, models, and some new findings (pp. 9-25). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marín (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 17-37). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. E. (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Betancourt, T. S., Abdi, S., Ito, B. S., Lilienthal, G. M., & Agalab, N. (2014). We left one war and came to another: Resource loss, acculturative stress, and caregiver-child relationships in Somali refugee families. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21(1), 114-125. doi: 10.1037/a0037538

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (2009). Culture and the evolution of human cooperation. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 364(1533), 3281–3288.https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2009.0134

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2003). Social isolation and health, with an emphasis on underlying mechanisms. Perspectives in biology and medicine, 46(3), S39–S52.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., Norman, G. J., & Berntson, G. G. (2011). Social isolation. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1231(1), 17–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06028.x

Cacioppo, S., Grippo, A. J., London, S., Goossens, L., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2015). Loneliness: Clinical import and interventions. Perspectives in Psychological Science, 10(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Campbell, W. S. (2008). Lessons in resilience undocumented Mexican women in South Carolina. Affilia, 23(3), 231–241.

Cornwell, E. Y., & Waite, L. J. (2009). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and health among older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000103

Davis, K. (2012). Friendship 2.0: Adolescents’ experiences of belonging and self-disclosure online. Journal of Adolescence, 35(6), 1527–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.013

Gardner, A., Filia, K., Killacky, E., & Cotton, S. (2019). The social inclusion of young people with serious mental illness: A narrative review of the literature and suggested future directions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 53(1), 15–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418804065

Goodenow, C., & Grady, K. E. (1993). The relationship of school belonging and friends’ values to academic motivation among urban adolescent students. Journal of Experimental Education, 62(1), 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1993.9943831

Hagerty, B. M., Lynch-Sauer, J. L., Patusky, K., Bouwsema, M., & Collier, P. (1992). Sense of belonging: A vital mental health concept. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 6(3), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9417(92)90028-h

Harrist, A. W., & Bradley, K. D. (2002). Social exclusion in the classroom: Teachers and students as agents of change. In Improving academic achievement (pp. 363–383). Academic Press.

Hawkley, L. C., & Capitanio, J. P. (2015). Perceived social isolation, evolutionary fitness and health outcomes: a lifespan approach. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 370(1669), 20140114. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0114

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2018). Why social relationships are important for physical health: A systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annual Review of Psychology, 69, 437–458. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

Kawai’ae’a, K.K., Housman, A.K., & Alencastre, M. (2007). Pu’a i ka ‘Olelo, Ola ka ‘Ohana: Three Generations of Hawaiian Language Revitalization. In Kawai’ae’a, K.K., Housman, A.K., & Alencastre, M. (2007). Pu’a i ka ‘Olelo, Ola ka ‘Ohana: Three Generations of Hawaiian Language Revitalization.

Kern, M. L., Williams, P., Spong, C., Colla, R., Sharma, K., Downie, A., Taylor, J. A., Sharp, S., Siokou, C., & Oades, L. G. (2020). Systems informed positive psychology. Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(4), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1639799

Kus-Harbord, L., & Ward, C. (2015). Ethnic Russians in post-Soviet Estonia: Perceived devaluation, acculturation, well-being, and ethnic attitudes. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 4(1), 66. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S2352-250X(15)00247-X/sbref0660

Leary, M. R. (1990). Responses to social exclusion: Social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 9(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221

Leary, M. R., & Kelly, K. M. (2009). Belonging motivation. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 400–409). Guilford Press. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-12071–027

Liebkind, K. (2001). Acculturation. In R. Brown & S. Gaertner (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology (Vol. 4, pp. 386–406). Oxford, United Kingdom: Blackwell.

Lim. (2009). Loss of Connections Is Death. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(6), 1028–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022109346955

McPhail, B. L. (2019). Religious heterogamy and the intergenerational transmission of religion: A cross-national analysis. Religions, 10(2), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel10020109

Manuelito, K. (2005). The role of education in American Indian self-determination: Lessons from the Ramah Navajo community school. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 36(1), 73–87.

Miller, S.C., 1982. Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Mitchell, D. D. K., & Middlesworth, N. (1992). Resource units in Hawaiian culture. Kamehameha Schools Press.

Moore, K., & McElroy, J. C. (2012). The influence of personality on Facebook usage, wall postings, and regret. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(1), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.09.009

Narchal, R. (2012). Migration loneliness and family links: A case narrative. In Proceedings of World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology (No. 64). World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology.

Nogelmeier, M. P. (2003). Mai Pa’a I Ka Leo: Historical voice in Hawaiian primary materials, looking forward and listening back. University of Hawai’i at Manoa.

Nguyen, A. M. D., & Benet-Martínez, V. (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of cross-cultural psychology, 44(1), 122–159.

Nguyễn, L. H., & Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation (2020). Pequot Warriors Combating Paper Genocide: How the Eastern Pequot Tribal Nation Uses Education to Resist Cultural Erasure. Journal for Undergraduate Ethnography, 10(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.15273/jue.v10i1.9945

Niens, U., Mawhinney, A., Richardson, N., & Chiba, Y. (2013). Acculturation and religion in schools: the views of young people from minority belief backgrounds. British Educational Research Journal, 39(5), 907–924. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S2352-250X(15)00247-X/sbref0605

Park, R.E., 1930. Assimilation, Social, in: Seligman, E.R.A., Johnson, A. (Eds.), Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, Vol. 2. Macmillan, New York.

Pember, M. A., & Today, I. C. (2022, December 27). Deaths at Chemawa. North Coast Journal. https://www.northcoastjournal.com/humboldt/deaths-at-chemawa/Content?oid=21797482

Petts, R.J. & Knoester, C. (2007). Parents’ Religious Heterogamy and Children’s Well-Being. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46(3), 373–389. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4621986

Phinney, J. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity development in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34–49.

Phinney, J. (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation. In K. Chun, P. Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–81). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

Phinney, J., Ferguson, D., & Tate, J. (1997). Intergroup attitudes among ethnic minority adolescents: A causal model. Child Development, 68, 955–969.

Phinney & Ong, 2007. Conceptualization and Measurement of Ethnic Identity: Current Status and Future Directions Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3). 271–281. DOI: I0.1037/0022-0 167.54.3.271

Rainey, K., Dancy, M., Mickelson, R., Stearns, E., & Moller, S. (2018). Race and gender differences in how a sense of belonging influences decisions to major in STEM. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-018-0115-6

Ruiz, J. M., & Steffen, P. R. (2011). Latino health. In H. S. Friedman (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Health Psychology (pp. 807–825). New York: Oxford University Press.

Rumbaut, R. G. (2015). Assimilation of immigrants. James D. Wright (editor-in-chief), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2, 81–87.

Sam, D.L., Vedder, P., Leibkind, K., Neto, F., & Virta, E. (2008). Migration, acculturation and the paradox of adaptation in Europe. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 5, 138–158.

Seabrook, E. M., Kern, M. L., & Rickard, N. S. (2016). Social networking sites, depression, and anxiety: a systematic review. JMIR mental health, 3(4), e5842. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.5842

Seidman, G. (2013). Self-presentation and belonging on Facebook: How personality influences social media use and motivations. Personality and Individual Differences, 54 (3), 402–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.009

Slavich, G. M., O’Donovan, A., Epel, E. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2010). Black sheep get the blues: A psychobiological model of social rejection and depression. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.01.003

Smith, T. B., & Silva, L. (2011). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: a meta-analysis. Journal of counseling psychology, 58(1), 42.

Spencer, S. J., Logel, C., & Davies, P. G. (2016). Stereotype threat. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-073115-103235

Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Depression and everyday social activity, belonging, and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015416

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Tingvold, L., Hauff, E., Allen, J., & Middelthon, A. L. (2012). Seeking balance between the past and the present: Vietnamese refugee parenting practices and adolescent well-being. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, (36), 536–574.

Walton, G. W., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364