10.4 Food Habits Begin in Childhood

Hearing the phrase “you are what you eat” might conjure a distinct image in a person’s mind. This phrase is often associated with encouraging a healthy diet to promote an individual’s overall well-being. Yet, food is not only a form of sustenance, but it is also used to communicate culture as well as a way of forming social ties and communicating love.

It is important to recognize the multidimensional influence food has on family life, and therefore how it can impact families in various ways. In particular, children are influenced by their primary caregivers’ habits, eating routines, and access to healthy food options.

Children and Nutrition

Children deserve a special mention when it comes to food, and especially to hunger as they are heavily impacted by poverty and hunger in the United States. In 2017, 17.5% of all children in the United States lived in poverty; Latin0/a/x and Black children were more often in poverty than were White children. This contributes to diet deficiency. A high-quality diet is a major contributing factor to children’s health and well-being and to their health outcomes as adults. Poor eating patterns in childhood are associated with obesity during childhood and adolescence; obese children are more likely to become obese adults. Obesity in children has been increasing dramatically since 1980 and is likely related to diet, physical activity, family environment and other factors. Obesity leads to increased risks for a wide variety of chronic diseases, including diabetes, stroke, heart disease, arthritis, and some cancers (Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics, 2019).

Hunger and a poor diet can have other effects on children. Hungry children cannot learn as efficiently as well-nourished children. According to the American Psychological Association, they are more likely to develop anxiety and depression along with other health problems. Brain development, learning, and information processing can all be affected by lack of an adequate diet. Children experience stigma around being food insecure and accessing free and reduced meals, part of the federal response to poverty. If you want to know more about this federally regulated and funded program, access the USDA website here. Many children receive USDA subsidized meals and snacks in childcare and at school (Figure 10.9). Children may feel isolated and ashamed about being poor or about being food insecure, although many children share this experience in the United States (American Psychological Association, n.d.).

Figure 10.9. Children eat fresh fruit in a childcare setting.

Early Food Experiences

The way our family approaches food when we are children affects us the rest of our lives. What we eat matters, as do the social aspects of meals. Some families eat meals together; others eat their meals individually in front of devices. People who were not exposed to a variety of foods as children, or who were forced to swallow every last bite of overcooked vegetables, may make limited food choices as adults. Children who do not have practice socializing during meals may not develop social skills or understand dining table social norms. A variety of factors—social, cultural, personal health, environmental, and experiential—affect how we eat, what we eat, and where we eat.

Social Factors

Any school lunchroom observer can testify to the impact of peer pressure on eating habits, and this influence lasts through adulthood. People make food choices based on how they see others and want others to see them. For example, individuals who are surrounded by others who consume fast food are more likely to do the same.

Advertising and media greatly influence food choice by persuading consumers to eat certain foods. Have you ever found yourself suddenly hungry after watching an advertisement for the local pizza place? The media affects both when we eat and what we eat.

Cultural Factors

The culture in which one grows up affects how one sees food in daily life and on special occasions. Food and family recipes are important ways to transmit culture across families and from generation to generation. Traditions and celebrations often include food.

People design their diets for various reasons, including religious doctrines. For example, Jewish people may observe kosher eating practices and Muslim people fast during the ninth month of the Islamic calendar.

Personal Health Factors

It can be easy to establish a habit around things we do each day. For example, having a dessert can become a habit. Having a snack after school or a drink with dinner can develop into a habit. Healthy habits such as “an apple a day” can be developed as well and may require intention on the part of the individual.

Some people have significant food allergies, to peanuts for example, and need to avoid those foods. Others may have developed health issues that require them to follow a low salt or gluten-free diet. In addition, people who have never worried about their weight have a very different approach to eating than those who have long struggled with excess weight.

In addition to one’s physical health, emotional issues can also affect eating habits. When faced with a great deal of stress, some people tend to overeat, while others find it hard to eat at all.

Environmental Factors

Where a person lives influences food choices. For instance, people who live in Midwestern U.S. states have less access to fresh seafood than those living along the coasts.

Based on a growing understanding of diet as a public and personal issue, more and more people are starting to make food choices based on their environmental impact. Realizing that their food choices help shape the world, many individuals are opting for a vegetarian diet, or, if they do eat animal products, striving to find the most “cruelty-free” or sustainable options possible. Purchasing local and organic food products and items grown through sustainable means also helps shrink the size of one’s dietary footprint.

Experiential Factors

Knowledge about healthful foods and calorie amounts affect food choices. This can be gained through family, peer, or media influence. Cooking knowledge is impactful. For example, knowing how to hydrate dried beans or prepare fresh vegetables could increase consumption of healthier foods. There has been a dramatic increase in television cooking shows in the 21st century, as well as nutrition, recipe, and cooking websites, blogs, and videos. The amount of information can make it hard to choose, but there are many options to learn about nutrition and cooking.

In Focus: Intergenerational Eating Influences

Elizabeth B. Pearce

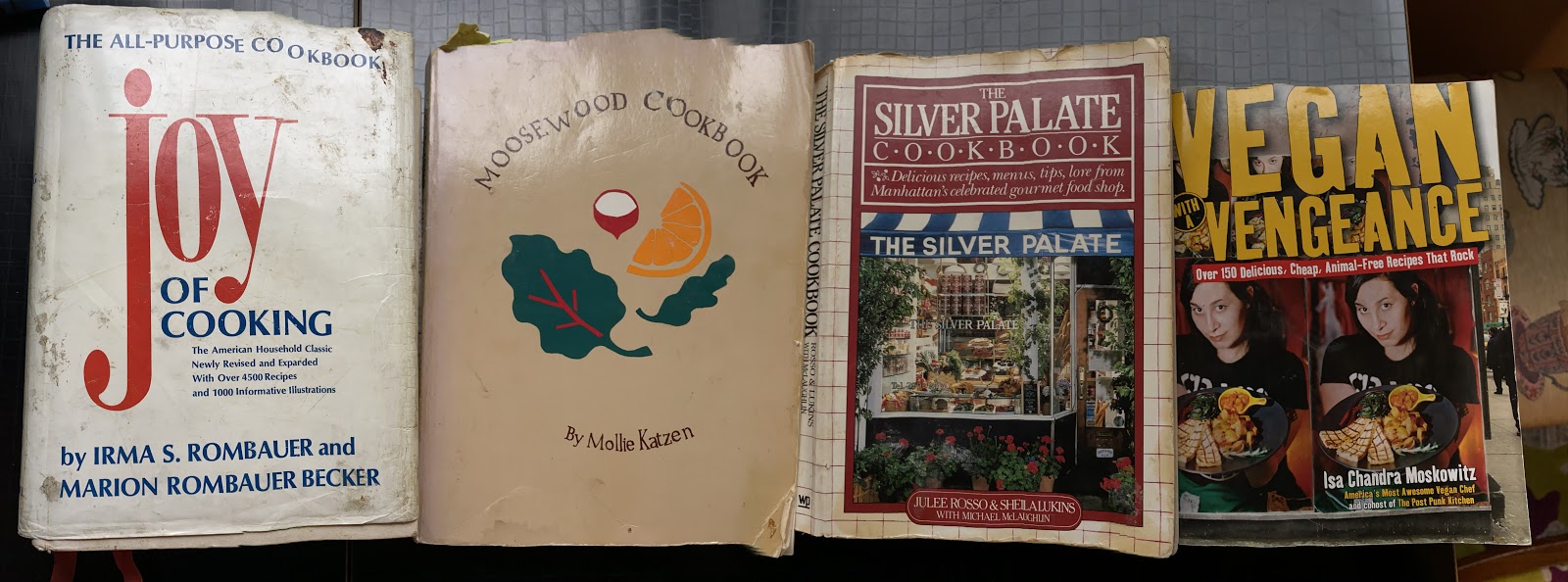

Figure 10.10. These cookbooks represent the owner’s evolution in cooking and eating, as influenced by first her mother, then her partner, and now her adult daughters.

Cooking food and sharing meals has been important to me all my life. My love of sharing food has not changed, but the people I share my everyday life with have. My mom was the cook in my family of origin; a typical dinner meal included meat, potatoes, and two vegetables. I remember The Joy of Cooking (Figure 10.10, left) as her “go-to” cookbook.

I’ve used The Moosewood Cookbook (vegetarian) and The Silver Palate (omnivorous) for over 30 years at home. Now I share food with my partner and with my adult daughters who choose vegan to mostly vegetarian eating. We still love cooking and eating together, but there is a lot more dialogue, debate, and compromise. Now I use a vegan cookbook to prepare some meals when my daughters come home for the weekend.

One thing that contemporary families in the United States have less now than they did 50 years ago is time. This is primarily due to the decreasing number of jobs with enough pay and benefits to support a family and the need for more adults in the house to be working. With less time, efficiencies such as fast food, processed food, and prepared food become more appealing. Having more time means that families have the flexibility to cook and prepare their own food if they choose.

Licenses and Attributions for Food Habits Begin in Childhood

Open Content, Original

“Experiential Factors” and “Environmental Factors” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Intergenerational Eating Influences” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 10.10. Photograph by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 10.9. “NCES Receives Fresh Fruits and Veggies Grant” by North Charleston. License: CC BY-SA 2.0.

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). What are the psychological effects of hunger on children? https://www.apa.org/advocacy/socioeconomic-status/hunger.pdf

Bauer, J. (2018, May 17). Oregon Lags in Fighting Food Insecurity. Oregon Center for Public Policy. https://www.ocpp.org/2018/05/17/oregon-food-insecurity-lag/

Charles, D. (2019, December 31). Farmers Got Billions From Taxpayers In 2019, And Hardly Anyone Objected. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2019/12/31/790261705/farmers-got-billions-from-taxpayers-in-2019-and-hardly-anyone-objected

Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2019). America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2019. https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/

U.S. Census Bureau. Farm labor. Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/farm-economy/farm-labor/

Vesoulis, A. (2020, May 13). The White House Pushes to Curb Food Stamps Amid Record Unemployment. TIME. https://time.com/5836504/usda-snap-appeal-rule-change/