11.4 Treatment, Jail, or Justice?

Christopher Byers

Preface

I always thought of myself as someone who has been the underdog in life. From my sister’s death, to homelessness, to drug addiction, I thought I had it worse than anyone in the world. My negative experiences played a role in shaping my belief systems about myself and the world around me and, in a way, encapsulated my thinking by keeping me “unique.” But then, that all began to change for me.

It all started with a class. In an HDFS class at Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC), I was introduced to a concept that altered my perception of the world and how I fit into it in a significant way. I began to learn how maybe after all these years of believing I had a hard life and everyone had it easy, this was not the case. I learned about concepts such as privilege, sociological imagination, equity, social constructivism, and many other concepts like those that helped me to slowly and, sometimes painfully, open my eyes to the reality of life. When I learned about privilege, I had the hardest time wrapping my head around that one. How could I, someone whose sister died, experienced homelessness, and drug addiction, be privileged? I thought at first that it didn’t apply to me. But through much internal reflection and writing and processing with people in my life and with my professor, I began to slowly understand what privilege means. That concept alone was a catalyst for me to dive further into researching injustice in the United States, and really inspired me to do a lot of deep reflective work on my own social identity and what it means to be who I am in the United States. This work has become some of the most important work I have ever done in my life. I see it as a path of healing not only for myself, but for many of us who choose to seek it.

Mental Health and Substance Use

Humans have been ingesting drugs for thousands of years. And throughout recorded time, significant numbers of nearly every society on earth have used one or more drugs to achieve certain desired physical or mental states. Drug use comes close to being universal, both worldwide and throughout history.

—Erich Goode

To the extent that social inequality, social interaction, and drug culture contribute to substance use, it is a mistake to attribute substance use only to biological and psychological factors. While these factors do play a role, it would be a mistake to ignore the social environments in which people participate in substance use. The role that the family plays in substance use potential is vastly underestimated. Weak family bonds and school connections are often seen as a major role in the development of substance use in adolescents. Weak bonds to family members prompt adolescents to be less likely to conform to conventional norms and more likely to engage in using drugs and other deviant behavior. Healthy family bonds, coping with trauma, learning how to identify feelings, and open communication all play a positive role in the reduction and prevention of potential substance use of family members in the future.

Mental Health

So what exactly is mental health? And how is it defined today? Well, first, let’s shine a brief but illuminating light on the history of mental disorders in the United States. The mentally ill have been treated very poorly for hundreds of years. In the 1800s, it was believed that mental illness was caused by demonic possession, witchcraft, or an angry god. For example, in medieval times, abnormal behaviors were viewed as a sign that a person was possessed by demons. This was not an uncommon societal belief in the 1700s. The idea that mental illness was the result of demonic possession by either an evil spirit or an evil god incorrectly attributed all inexplicable phenomena to deities deemed either good or evil (Lumen Learning, n.d.). The prevailing theories of psychopathology, derived from folklore and inadequate scientific beliefs, are still perpetuated today. Although science has a better understanding of mental health, it is still common for stigma, discrimination, and ignorance to be the deciding factors in how people with mental health are cared for and treated.

Psychological disorders are very common in the United States, yet there is still a great deal of inequity that encompasses mental health issues. Stigma, labeling, ignorance, discrimination, and judgment are all still very prevalent and harsh realities in our society today. The biological, sociological, physiological, and cultural determinants of mental health disorders vary from case to case, and most mental health issues are still often difficult to understand, as the roots of mental illness are often misunderstood (Figure 11.7).

Figure 11.7. Mental health is a part of our overall health.

Our society has made a lot of progress in understanding how some mental health disorders operate, but we still have a ways to go until we as a society can see mental health through a collective, compassionate lens. It is important to remember that those who struggle with psychological disorders are not their disorder. It is something they have, through no fault of their own. As with cancer and diabetes, these people who have psychological disorders often suffer from debilitating, often painful, conditions through no choice of their own. These individuals deserve to be treated and viewed with compassion, dignity, and understanding.

Substance Use Disorder

So what exactly is the relationship between substance use disorder and mental health? Substance use disorder (SUD) is a disease that affects the brain and includes the uncontrolled use of something despite harmful consequences (sometimes called substance abuse). SUD and mental health are interconnecting and overlapping systems. There have been many years of stigma, discrimination, and misunderstanding toward people who have both mental health issues and SUD issues. Many people who suffer from SUD often have unaddressed trauma, depression, anxiety, and environmental and genetic factors that contribute to the use of substances as a way to self-medicate and cope with how they feel, regardless of the negative consequences that might happen as a result of using. For example, conduct disorder and antisocial personality disorder are strongly associated with the development of both substance use and serious mental illness such as major depression and bipolar disorder. Some SUD can even mimic mental health issues, making a diagnosis difficult without dealing with the SUD issues first. Psychopharmacological reactions to withdrawal can also induce psychiatric symptoms and exacerbate underlying mental health issues for people as well.

Mental health issues are interconnected with SUD. Most people who practice counseling often deal with the SUD issues with a client and then proceed to determine if that individual is suffering from mental health issues after the SUD is addressed.

The Criminalization of Drugs

Although slavery has been abolished and Jim Crow laws are no longer legal, the systems that have oppressed POC and marginalized communities for over 300 years continue. It can be argued that the criminal justice system and the legislation and policies that were created to punish drug users and drug crimes were designed to perpetuate discrimination and oppression of POC at disproportionate rates.

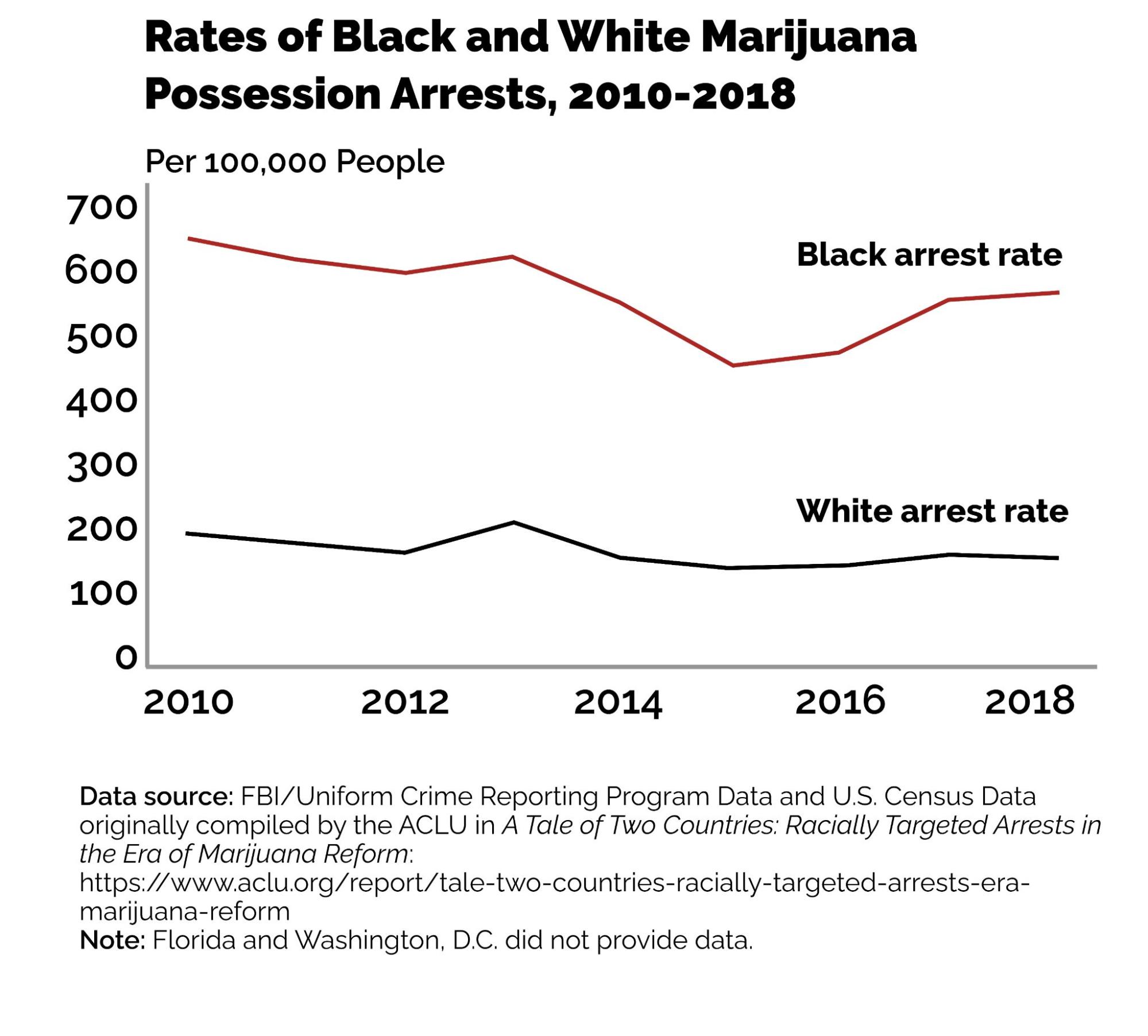

A significant aspect of the War on Drugs, a piece of legislation that disproportionately affected POC in the United States, was that it imposed mandatory minimum sentencing laws that sent nonviolent drug offenders to prison, rather than enrolling them in treatment programs. Seventy percent of inmates in the United States are POC—a figure that surpasses the percentage of this demographic group in U.S. society, which is approximately 23%, according to the 2015 U.S. census. That means that POC are greatly overrepresented in the U.S. criminal justice system. The United States has the highest incarceration rates for drug-related crimes. Figure 11.8, based on the article “The Black/White Marijuana Arrest Gap, in Nine Charts,” demonstrates the implicit bias our justice system still has for POC in the United States.

Figure 11.8. Black people are disproportionately arrested for marijuana possession compared to White people.

It is a sad and common societal view that addicts and SUD users are lesser human beings, a lower standard of individual than the rest of society. This is an example of stigma. This overarching and negative view of people who struggle with SUD plays a role in the passing of policies and criminalization of millions of people every year in the United States, which disproportionately affects families of color. When POC are targeted for nonviolent drug-related crimes, they are more likely to receive harsher punishments than White people. This has damaging consequences for POC and their families, with the head of households usually being the ones who receive these harsher punishments.

Women of color have been arrested at rates far higher than White women, even though they use drugs at a rate equal to or lower than White women. Furthermore, according to Bureau of Justice statistics from 2007, nearly two-thirds of U.S. women prisoners had children under 18 years of age. Before incarceration, disproportionately, these women were the primary caregivers to their children and other family members, so the impact on children, families, and communities is substantial when women are imprisoned.

Inmates often engage in prison labor for less than minimum wage. When these individuals are incarcerated, corporations contract prison labor that produces millions of dollars in profit. Therefore, the incarceration of millions of people artificially deflates the unemployment rate (something politicians benefit from) and creates a cheap labor force that generates millions of dollars in profit for private corporations. How do we make sense of this? What does this say about the state of democracy in the United States?

When seen through an equity lens, we can establish some interesting points. One is that the rates that POC and White people use drugs are about the same, but one important factor plays a role in the disproportionate rates of incarceration for POC: implicit bias. People have subconscious ideas about who uses drugs in the United States. These ideas are based on false narratives derived from implicit biases that perpetuate the inequitable incarceration of POC. Secondly, the War on Drugs focused and funneled money into the punishment of and incarceration for drug-related offenses.

A question to ponder is this: what would society look like if instead of punishment and criminalizing drug use and drug users, we used that money to focus on treatment, recovery centers, and social services?

Licenses and Attributions for Treatment, Jail, or Justice?

Open Content, Original

“Treatment, Jail, or Justice?” by Christopher Byers. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 11.8. “Rates of Black and White Marijuana Possession Arrests, 2010–2018” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi-Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 11.7. “One and Other-Mental Health” by Feggy Art. License: CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

This section was adapted from “The State, Law, and the Prison System” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken. License: CC BY 4.0 International License.

References

Lumen Learning. (n.d.). The state, law, and the prison system. Retrieved September 3, 2020, from https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-introwgss/chapter/the-state-law-and-the-prison-system/