12.2 Experience, Expression, and Equity

Elizabeth B. Pearce, Christopher Byers, and Carla Medel

If you have only two pennies, spend the first on bread and the other on hyacinths for your soul.

—Arab Proverb

Figure 12.1. This community mural of two boys in nature can be found in Comuna 13, a neighborhood in Medellín, Columbia.

Visual culture is described as the combination of visual events in which “information, meaning, or pleasure” are communicated to the consumer (Mirzoeff, 1998). The information that we take in through our eyes is both immense and psychologically powerful, affecting us in ways that take time and cognition to understand (Figure 12.1). It is the intent of this chapter to highlight the ways in which visual culture affects families, both in the way we view ourselves and in the ways we can access resources such as education, employment, and wealth.

Art is one way people share ideas, express themselves, and communicate. Consider the print of Claude Monet’s The Water Lily Pond hanging in your doctor’s office (Figure 12.2). What about the graffiti you passed on the way to the bus stop? Artistic expression exemplifies the richness of a culture and energizes our thought processes. We are exposed to art, design, and creativity all day long, whether we realize it or not.

Figure 12.2. The Water Lily Pond by Claude Monet hangs in the Albertina, a museum in Vienna, Austria, but reproductions of Monet’s art can be found everywhere.

Art is one way in which people share ideas, express themselves, and communicate. How and where an individual is able to access art is largely related to the values and beliefs a culture holds as a standard for determining what is desirable in a society, both by artistic and by beauty standards.

Individuals have specific, individualized beliefs, but can still share collective values. Values shape how a society views what is considered beautiful and what kinds of art are valued. Beauty is a concept that is flexible and that changes depending on where and when you are living. A family’s access to art that speaks to their culture, interests, and imagination depends on what is available in the popular media and accessible in their geographic region. In western culture, art was historically housed in museums. In Indigenous cultures, art often takes the form of useful objects, such as baskets, an example shown in Figure 12.3, and clothing.

Figure 12.3. In the western Apache culture, women traditionally produced storage baskets for family use. This basket, likely made in Arizona circa 1890, is now housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Today art and other imagery are easily accessible in digitized forms of technology, which are accessed through the internet. These readily available ways that people can use and access visual culture can breed unrealistic expectations for many people.

For example, with the rise of “selfies,” social media platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat can provide individuals outlets to shape and shift self-images so that they can conform more easily to the dominant social standard of beauty.

It can be posited then that the dominant culture’s expectation of physical beauty can and has been what has most heavily influenced western culture. The media and films portray a particular standard of beauty, setting up a tension between conforming to this standard, individualistic preferences, and cultural practices that may conflict with the idealized concept of beauty.

Beauty perceptions affect family members of all ages; the multidirectional relationship of families and society affects the parents and guardians of children, which in turn affects the kids, and the grandkids, and so on. The patterns are shown in the ways we rear our children, which is the emotional connection within the private family.

Art: A Historical Context

Expression is a fundamental need for human beings. Some human developmental theories, like Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory, demonstrate that once humans have their basic needs met, such as food, water, shelter, love, nurturance, and housing, they can begin to move into more creative avenues of self-expression and self-actualization.

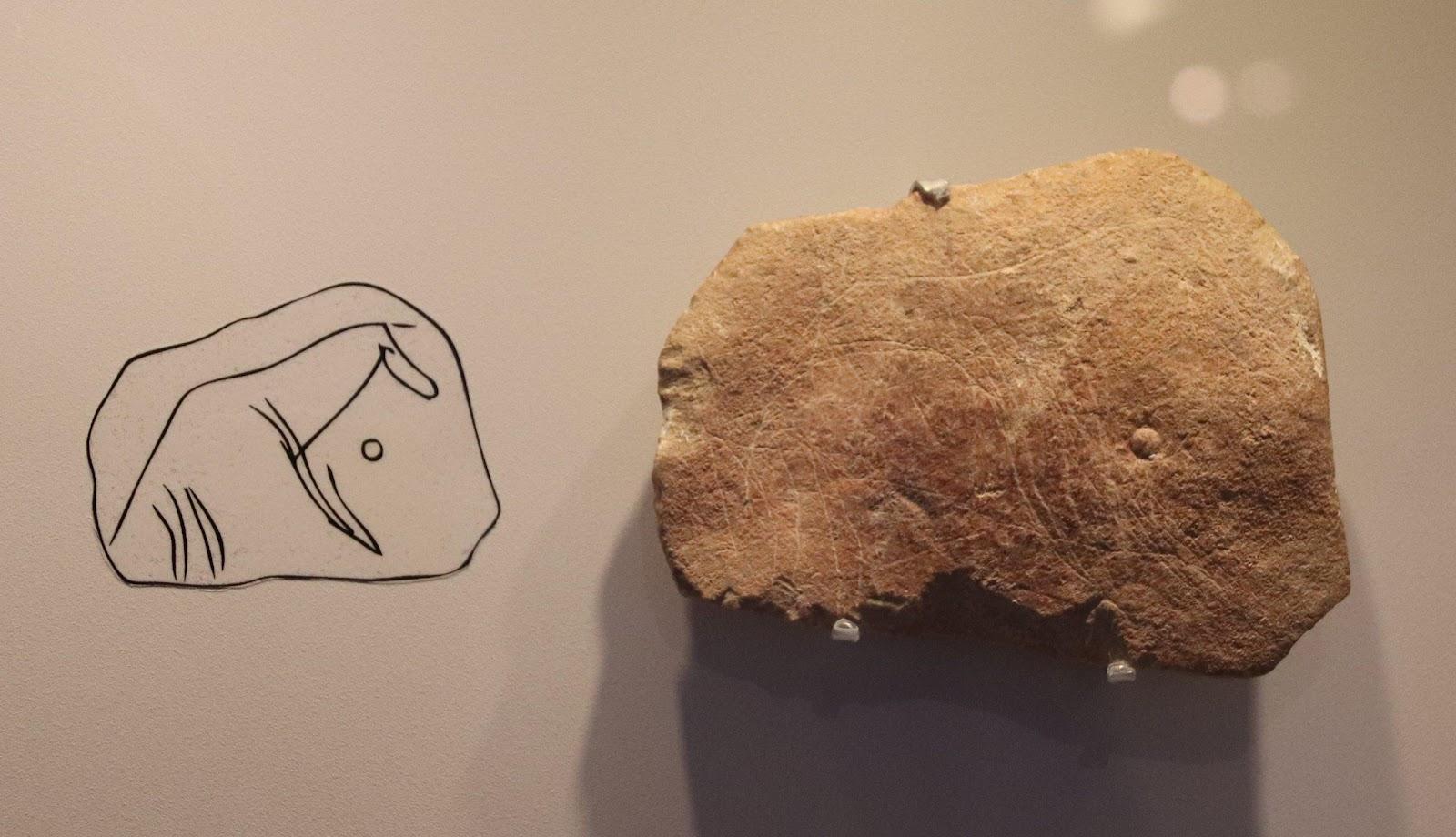

Throughout history, humans have produced artworks. One would be surprised at how far back in time humans were attempting to engage in expression. Scientists have recently found shells dating back 500,000 years ago that were engraved with small geometric incisions on the surface (Callaway, 2014). While these shells can be debated to be considered art by historians, it’s important to note that long before the concept of “art” was created, homo sapiens were trying to do it (Figure 12.4).

The question “What is art?” is one that continues to be debated. Some art historians believe that the oldest piece of art to date has been discovered and originated from the Late Stone Age and the Upper Paleolithic Period, from between 70,000 and 40,000 BCE.

Figure 12.4. This prehistoric art carving was made circa 26,000 BCE.

Throughout history, art has been passed down from our families, rituals, and ceremonies that are given to us by our communities and interactions with the dominant culture (Breen, 2008). Do human beings have equitable access to create art now? Are there barriers that are present in the lives of individuals today that make it difficult or impossible to be able to engage in self-expression? Systemic barriers that limit families in the United States from meeting basic needs also inhibit equitable access to self-expression.

Using Art to Teach

Visual representations are strong; the popular saying, “a picture is worth 1,000 words,” speaks to this power. When it comes to teaching history in the high school setting, it has been found that art is a powerful pedagogy that moves students beyond the understanding that they gain from text alone. Students develop more interest in history, and the potential for examining multiple viewpoints via artistic representation can help students to develop critical thinking skills related to understanding history.

Younghee Suh summarizes much of the literature related to how students absorb history via artistic representations (visual, photographic, and musical among others) in the study, “Past Looking: Using Arts as Historical Evidence in Teaching History” (Suh, 2013). Suh focuses on pedagogy and notes that the way in which teachers expose students to art highly influences students’ abilities to sort fiction from fact. Exposure to art from the past is not enough, however. Teachers must also provide scaffolding to students that helps them to consider the perspective of the artist, the time in history, and the choice about which art is included in textbooks and other historical summaries. Without this guidance and contextualization, learners are left to see representations as “fact” instead of a particular viewpoint of the past.

Many history books (and the accompanying artistic representations) are presented from the viewpoint of the Euro-American settlers. It is important that we understand the experience of all families, not just the families who belong to the culture that now dominates. In the process of establishing dominance, Indigenous families were harmed. For example, children were frequently separated from the rest of the family and sent to schools where they were harshly punished for speaking their native languages and practicing their religions (Little, 2018). Violence against Indigenous women was and is still perpetuated at higher rates than against women of other races, and is underreported and under prosecuted (Amnesty International, n.d.).

Another example of the cultural context of art comes from Linn-Benton Community College in Albany, Oregon. A student made this observation in an art history class: “I took an art class and when my teacher was showing a painting of the Virgin Mary it seemed very normal to everyone in my class except for me, until she showed a picture of the Virgin Mary the way that Latinos are used to seeing her (the one on the left in Figure 12.5 is a Mexican depiction of Virgin Mary and the one on the right is Italian). If my teacher would have never said that it was Virgin Mary who was depicted in the art, I would’ve never known because that’s not how I have seen Virgin Mary growing up.”

Figure 12.5. Here are two artistic representations of the Virgin Mary On the left is part of a 16th-century shrine located at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, Mexico. On the right is the Madonna del Granduca by Raphael (1505), which hangs in the Pitti Palace in Florence, Italy.

The Virgin Mary is associated with qualities considered positively in western culture, which include purity and beauty. Look closely at these images in Figure 12.5 to see how the expression of those characteristics are represented.

A discussion of art needs greater exploration and explanation, but the point of this section is to illustrate the ways in which art always has a viewpoint. While the dominant cultural viewpoint is the one most often seen, art can also be used to express other viewpoints and to initiate critical discussion about the past as we will explore in the next section.

Licenses and Attributions for Experience, Expression, and Equity

Open Content, Original

“Experience, Expression, and Equity” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Christopher Byers, and Carla Medel. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Art: A Historical Context” by Christopher Byers and Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Using Art to Teach” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 12.1. “Photograph of Street Art in Medellín, Colombia.” License: CC0.

Figure 12.2. “Water Lily Pond” by Claude Monet. Public domain.

Figure 12.3. “Storage Basket (Apache), ca. 1890” from the Charles and Valerie Diker Collection of Native American Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Public domain.

Figure 12.4. “Stone Age Animal Carving, Hayonim Cave, 28000 BP” by Gary Todd (photographer). License: CC0 1.0.

Figure 12.5. “Virgen de Guadalupe.” Public domain. “Madonna del Granduca” by Raphael. Public domain.

References

Amnesty International. (n.d.). Maze of injustice. https://www.amnestyusa.org/reports/maze-of-injustice/

Breen, R. (2008, November 26). Towards a collective understanding of art as a commons. On the Commons. http://www.onthecommons.org/towards-collective-understanding-art-commons

Callaway, E. (2014, December 3). Homo erectus made world’s oldest doodle 500,000 years ago. Nature News. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature.2014.16477

Little, B. (2018, Nov. 1). How boarding schools tried to “kill the Indian” through assimilation. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/how-boarding-schools-tried-to-kill-the-indian-through-assimilation

Mirzoeff, N. (1998). What is visual culture? In N. Mirzoeff (Ed.), The visual culture reader (2nd ed., pp. 3-13). Routledge.

Suh, Y. (2013). Using arts as historical evidence in teaching history. Social Studies Research and Practice, 8(1), 135-159. http://www.socstrpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/MS_06372_Spring2013.pdf