13.4 Gender, Work, and Family

Intertwined with the idealized nuclear family is the gendered work world, or separate spheres, in which men went to paid work, and women took care of the home, the children, and the man’s needs. But as we have discussed throughout this text, not only was this idealized family able to exist as a majority for a very short period of time, it also excluded many families. As we know, one of the ways that families have changed in the United States is directly related to the continued decline of the economy after its peak in the mid-1970s, which means that many more families need to have all the adults (whether one adult, two adults, or more) in any given household employed with paid work. In this section we will focus primarily on gender, because of its significant role in family ideals, but we will also touch on other social identities.

Occupational Segregation

The workplace has seen many changes in the last few hundred years. One of the first groups fighting for working women’s rights was the Daughters of Liberty, formed in 1765. (Sweet, 2021). In 1873, the Supreme Court ruled that women were prohibited from practicing law. The finding stated, “it was natural and proper for women to be excluded from the legal profession” as women were expected to fulfill “the duties of motherhood and wife.” (Oyez N.d.). Positive progress was made toward gender equality in the workplace with the passage of the Equal Pay Act in 1963. It stated that companies could not pay people differently for the same work based on gender.

Figure 13.14. Captain Amy Bauernschmidt became the commanding officer of the USS Abraham Lincoln in 2022. She is the first female captain of an aircraft carrier in the U.S. Navy.

More recently, in 2013, the U.S. military allowed women to serve in previously closed combat designations. 2022 saw the first female aircraft carrier captain in the history of the U.S. Navy, Captain Amy Bauernschmidt, shown in Figure 13.14. When Captain Bauernschmidt started her career at the U.S. Naval Academy in the early 1990s, women were prohibited from serving on combat ships (Lendon et al., 2022). Additionally, transgender people have been allowed to openly serve in the U.S. military as of 2016.

In Focus: Military Workplace Policies and Family Formation

The branches of the military, which include the Army, Marine Corps, Navy, Air Force, and Coast Guard, are funded by the federal government. As the employer, the federal government has particular policies that apply to families. Two of the most well-known apply to relationships, sexuality, and marriage.

For the majority of this nation’s military history, members of the LGBTQ+ community have been disqualified from employment and service. This doesn’t mean that they didn’t serve, but they were stigmatized and hidden. The policy changed between 1994 and 2011, when the infamous rule “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell, Don’t Pursue” (Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell) was in effect. During this time, gay men, lesbian women, and bisexual people were permitted to be employed as long as they did not exhibit or talk about conduct that could be identified in these ways; in addition, others were prohibited from discriminating against or harassing them. The “Don’t Pursue” aspect of the regulation limited the investigations by superiors of members presumed to belong to the LGBTQ+ community.

The law, which appeared to signify progress, still resulted in many members of the military experiencing stigma, stalled careers, discrimination, harassment, and violence. Multiple legal challenges were filed, and it was eventually repealed. While the regulation has changed, stigma and harassment remain.

Necko L. Fanning, wrote this in The New York Times about his experience serving in the Army between 2011 and 2014 (Fanning, 2019):

The second week after I arrived at Fort Drum, New York—my first and only duty station with the Army—I found death threats slipped under the door of my barracks room. I noticed the colors first. Pink, blue, and yellow; strangely happy colors at odds with the words written on them. Some were simple: slurs and epithets written in thick black Sharpie, pressed so hard into the paper that it bled through. “Faggot” and “queer fag,” the notes read. A couple were more elaborate: detailed descriptions of what might happen to me if I was caught alone, and proclamations about the wrongness of gays in the military.

The military is built on a foundation of earning trust and proving yourself to your peers and superiors as capable. Being new to a unit isn’t unlike being a new employee at any other job. People are cautious, even wary, until you’ve shown you can handle the work.…My capability wasn’t in question, nor was my duty position. It wasn’t my effectiveness or value to the unit that elicited these noxious notes but something far removed from my control. Something that after September 2011 was supposed to be meaningless.

The military has also been known for policies that incentivize marriage. In general, single members of the armed forces live in barracks with a large group of colleagues. Married members, in contrast, live in military housing that more closely mimic suburban neighborhoods, which is pictured in Figure 13.15. In addition, there is a housing allowance that goes along with this privilege, resulting in married military members earning more salary and benefits.

Figure 13.15 This photograph is used to market and to advertise newly constructed housing benefits for the U.S. “Airmen” and families in 2017.

This incentive is provided by the military in order to support and stabilize families who are frequently moving and have less predictable work schedules than other government positions. Could this contribute to marriages made for financial reasons? Or to project heterosexuality? Anecdotally, yes, there are many stories that support this theory. When taken in combination with the prohibition of LGBTQ+ people’s service, it could also serve as a double incentive: a way to avert suspicion of unsanctioned sexuality as well as a financial gain. But getting married is a complex decision and it is difficult to attribute only one factor in the decision to get married.

Women are currently not restricted by laws specifically preventing them from participating in the labor force. Due to societal norms, women tend to choose lower-paying jobs, which reinforces the gender wage gap. Higher-paying jobs such as pilots, finance, corporate executives, and technical services are male-dominated. Jobs seen as more suited to women’s socially prescribed gendered norms of empathy and caregiving typically pay less. These lower-paying jobs include home health care workers, elementary school teachers, and nurses. Gendered societal expectations are taught to us from an early age through agents of socialization, including family, peers, religion, and media.

While gendered norms have become more balanced in most industries in recent decades, stereotypes still exist. There are many benefits to all workers, employees, and companies when people of all genders are included in a diverse range of industries. For the medical industry, having a more balanced representation of employees across all demographics provides a positive workplace for employees and better patient health outcomes (Gomez & Bernet, 2019). Addressing equal gender representation in decision-making arenas such as corporate CEOs and the Supreme Court may improve workplace equality for all genders.

Barriers to Workplace Advancement

Many obstacles still exist when it comes to achieving gender equality in the workplace. Sometimes these barriers have been institutional, such as legally restricting women’s participation in military combat roles. Sometimes, people’s prejudices prevent equal gender participation in the workplace. There were times, such as in the early 1900s, when women were thought to be so delicate they could not understand complex scientific work such as chemistry and physics. People believed that thinking hard about complex situations or work-related stress would physically harm women.

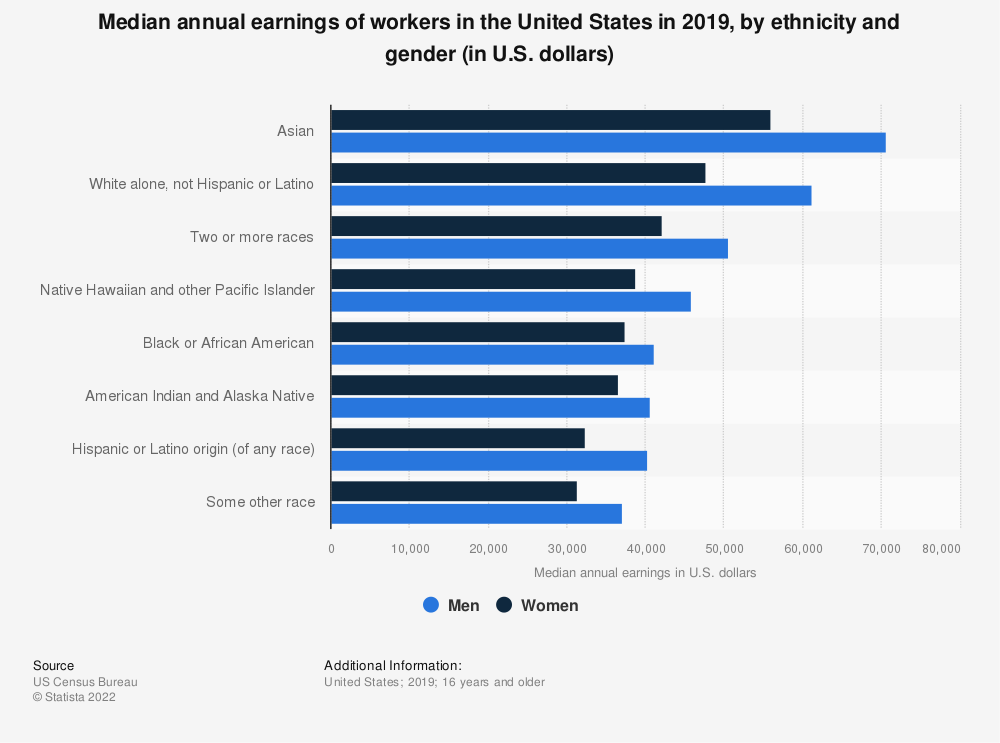

The outlook is particularly challenging for people who encompass intersectional diversity, such as Black women who are single heads of households. Barriers to employment due to sexism, racism, income, parental status, and urban residence further restrict employment and advancement opportunities. These barriers are highlighted by looking at the median annual earnings for workers in Figure 13.16. Worker income represented in the table for 2019 shows Latina women earn far less than other intersectional groups of race and gender.

Figure 13.16. This graph shows the median annual earnings of workers in the United States by ethnicity and gender (in U.S. dollars), 2019. For all ethnicity categories, women earn less than men.

Transgender workers face high levels of discrimination, even though federal laws regarding workers’ rights protect them. Transgender workers have unemployment rates three times higher than cisgender people, leading to economic instability (James et al., 2016).

Gender discrimination in the workplace has a long history, but progress is being made toward equal opportunity. Societal attitudes on gendered workplace stereotypes can help move or dissolve workplace barriers for all genders. Labor force opportunities for all genders have changed due to diversity, equity, and inclusion trainings, mentoring programs, and expanded access to childcare.

In early 2022, signaling another seismic shift in creating inclusive workplaces, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) added the nonbinary self-identification option to discrimination report forms. Although many institutional barriers have been removed from the workplace, disparities continue for access, placement, benefits, and promotions.

Gender self-presentation is also intertwined with the workplace. What we wear, our hair choices, body modifications (piercings and tattoos), and use of cosmetics influence how others see us. In many industries, “professional” clothing is a dark-colored suit with a dress shirt and tie, which is traditional masculine workplace attire. Wearing a suit then means you should be taken seriously and have excellent knowledge about a subject. Suppose you wear clothing with pastel shades or flowery patterns, which are considered stereotypically female. In that case, you might be viewed as not committed to your profession, not as intelligent or reliable. Societal pressure to adhere to masculine normative workplace clothing is evidenced by women and nonbinary altering their workplace attire to more closely match men’s traditional styles rather than men changing their clothing choices to match women’s.

Figure 13.17. Professional people face obstacles in the workplace through gender-specific and Eurocentric expectations for presentation of self.

Black women, in particular, experience discrimination based on the presentation of natural hair textures and styles in the workplace. Figure 13.17 shows professional people with non-Eurocentric hairstyles. Wearing a non-Eurocentric hairstyle has negatively affected Black women’s employment and promotion opportunities into leadership roles (Koval & Rosette, 2021). Women of color have been litigating for years for the acceptance of natural hair in the workplace, often with inconsistent outcomes.

Invisible Barriers

Although women make up nearly half of the U.S. workforce, only about 15% of Fortune 500 companies had female CEOs by early 2022. This is a notable increase from 1.4% in 2002 (Buchholz, 2022). The glass ceiling is the lack of advancement opportunities for non-males in high-level positions. This invisible barrier, due to a variety of factors, prevents non-males from achieving positions of power. Power in the workplace may include deciding how to spend the company’s money, who gets hired or fired, or what products to make.

In some industries, such as nursing, nontraditional gender workers are advanced at a higher rate. This quick movement from entry-level to power-holding, higher-paying leadership jobs is called the glass escalator. Males are nontraditional gendered workers in the nursing profession, making up 12% of nurses in 2021 (BLS, 2021). Yet somehow, nearly half of nursing leadership roles are held by men. Researchers attribute this phenomenon to both the glass ceiling and the glass escalator. Research has shown that White males mostly benefit from the escalator while male nurses of color do not (Bradford & Bradford-Stevenson, 2021).

Sociologists studying the workplace found another type of gender inequity, the pattern of behavior known as the glass cliff. This occurs when women are purposefully promoted into positions with a high risk for failure. This typically occurs when companies are already experiencing problems. Promotions with significant increases in pay and responsibility are difficult to pass up, even with the likely harmful outcome. Research shows that when women are placed on a glass cliff, this reinforces the stereotype that they are poor leaders (Kagan, 2022).

Women on the glass cliff have higher-level roles in companies, but this is still not common overall. Many women find themselves stuck on the ground floor of the employment power ladder. The sticky floor refers to positions typically held by women, where advancement to the next level of power is difficult. Poorly paid and unstable jobs, such as entry-level, administrative, and human service workers, are particularly vulnerable to the sticky floor syndrome. If women in these roles lack formal education or financial stability, they are not often able to leave these dead-end jobs.

Companies can work on mitigating the glass ceiling, glass escalator, glass cliff, and stick floor in many ways. To start, fellow employees and corporate leaders need to recognize the existence of these workplace issues. Human resource departments or outside consultants can use diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to openly discuss these problems in a safe space. Companies in difficult situations that promote women and people of color into professionally hazardous roles can ease the negative impact on employees by creating a culture of diversity and mentoring for success in higher executive levels.

Working Parents Face Additional Barriers

In 2022, across all professions, women make approximately $0.82 for every $1.00 men make (Payscale, 2022). Native American women fare the worst when race and gender intersect, making approximately $0.71 compared to White men’s $1.00 (Miller, 2022). Much of this has to do with society’s gendered norms steering women into low-wage positions. But it is also related to the roles that women play in childbearing and childrearing, and at least as importantly, the roles that prospective employers expect them to play.

Gaps in career progression due to pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, and eldercare issues restrict promotion potential, which is an additional source of pay inequity over a lifetime. In general, for all workers, a female parent’s pay is about $0.74 to a male parent’s $1.00 (Payscale, 2022). Female heads of households are acutely susceptible to fluctuations in the economy. This can bring about role conflict, which is a situation in which contradictory, competing, or incompatible expectations are placed on an individual by two or more roles held at the same time. Role conflict for single parents finds them struggling to fulfill work obligations while also meeting their family’s needs. The instability of work can negatively impact employee finances and seriously impede wealth building for their future retirement.

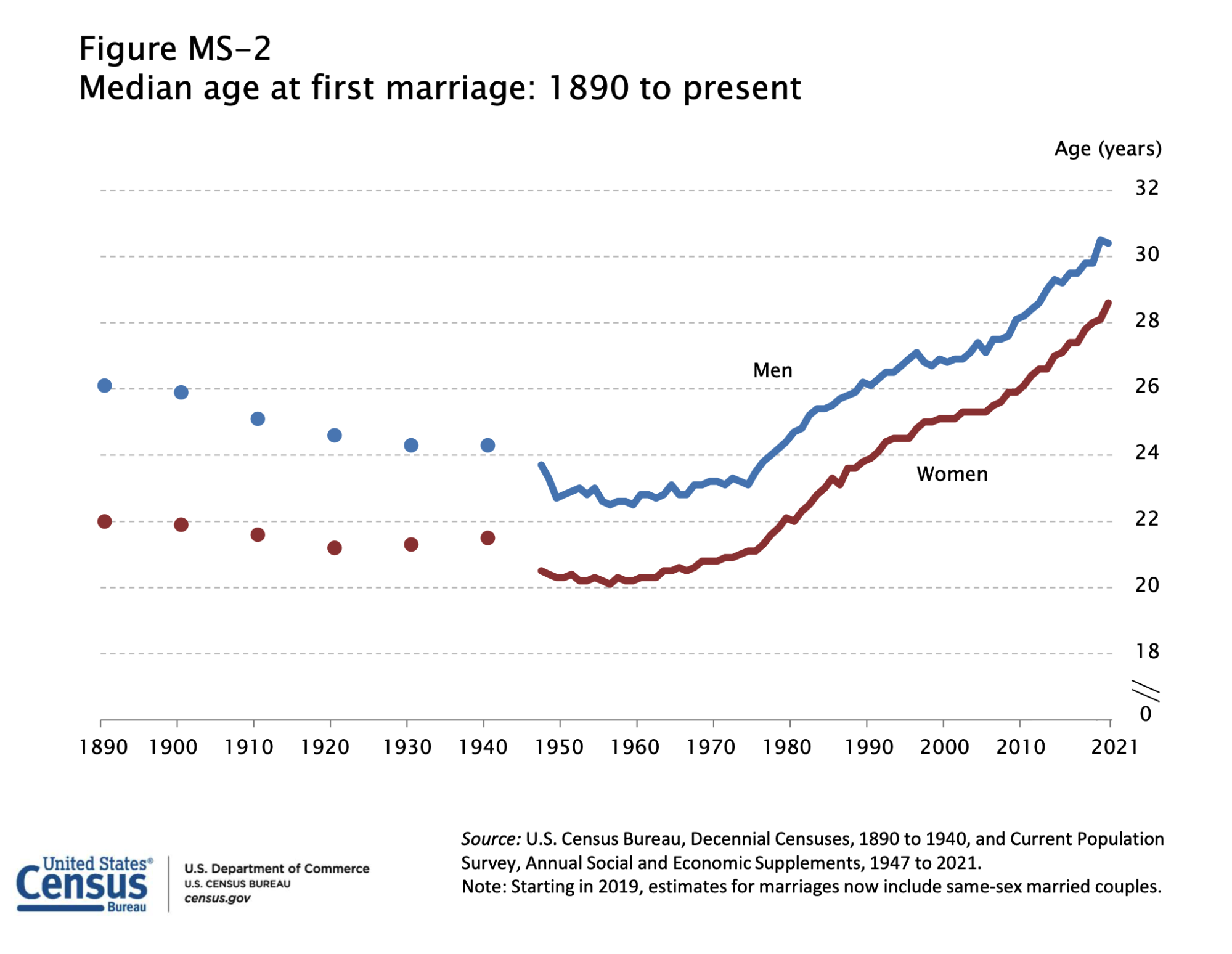

Single parents face discrimination based on societal assumptions that their parental role may interfere with them fulfilling their job responsibilities. Societal gender expectations we have today are rooted in historical societal norms. In the early 1900s, laws existed legally forbidding married women from working. There were also societal pressures encouraging women to leave the workforce when they got married. Even though marital age has risen over the last 50 years, the public’s perception that women cannot physically work or should not participate in the workforce when married or pregnant persists. Figure 13.18 shows the changing dynamic of age at first marriage historically. There is a correlation between when women increasingly earned bachelor’s degrees in the 1980s and 1990s with the noticeable increase in the age at first marriage as seen on the chart.

Figure 13.18. As women strengthened their participation in the workforce, the age of first marriage increased for the genders measured.

As more women entered the primary sector labor market and assumed white-collar roles, greater protections were demanded for working parents. Changing societal norms acknowledged discrimination against working parents, including nursing or adoptive parents. The Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) was passed in 1993. The FMLA protects employees from firing or losing benefits while away from work for specific family or medical reasons. Although legal protections exist for pregnant people, such as the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) passed in 1978, employers still discriminate against pregnant workers. Newly married individuals may be perceived as looking to start or expand a family, thus unreliable as future workers. In 2020 just under 400 pregnancy discrimination lawsuits were filed in federal court (Sear & Goldstein, 2021). Parents on parental or adoption leave may miss out on meetings or other work, which is then used to justify passing them over for promotions, thus reinforcing pay inequities.

Access to pregnancy and family leave policies can strengthen workforces across all industries and all levels of employment. Company cultures flexible with family leave will see positive returns from their employees and the company overall. One study found that paid leave policies “led to improved infant health, with the largest effects on disadvantaged African American and unmarried mothers” (BLS, 2019).

Black women are especially susceptible to barriers in the workplace due to “unacceptably high rates of chronic illness as well as tragically high rates of maternal and infant mortality. In fact, Black women, as well as their infants, are significantly more likely to die in the weeks after birth than are any other group of people” (Milli et al., 2022). Chronic illnesses due to a lack of access to affordable health care and concerns about taking time away from work for medical care negatively impact not just the workers, but companies who have to deal with prolonged gaps in their workforce. Black female workers’ medical instability can also harm their chances of being hired or promoted due to misperceptions of them being unreliable workers.

This creates a cycle of oppression for women and people of color in the workforce. In a 2019 report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Latinox workers were found to have the lowest access to paid leave for childcare or eldercare of all race categories. When faced with these life challenges, Latinox workers do not have financial or employer support for missing work, which creates financial hardships (BLS, 2019). Taking time away from work for childcare or eldercare crises may also indicate to employers the worker is unreliable or not focused on their job.

The intersectional nature of some workers’ demographics and life experiences can negatively affect their pay and work opportunities. In this section we have highlighted how being a parent, or being of childbearing age, offers another identity that faces pay discrepancies and pay discrimination. Such concerns are the basis of unconscious and conscious biases in the hiring and promotion processes.

Licenses and Attributions for Gender, Work, and Family

Open Content, Original

“Gender, Work, and Family” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Military Workplace Policies and Family Formation” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 13.15. “New Military Family Housing Benefits Airmen” U.S. Air Force. Public domain.

“Occupational Segregation” adapted from “Occupational Segregation” by Jane Forbes in “The Sociology of Gender” [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: editing for brevity.

Figure 13.14 Captain Amy Bauernschmidt by the Naval Air Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet is in the Public domain.

“Barriers to Workplace Advancement” and “Invisible Barriers” adapted from “Barriers to Workplace Advancement,” “Invisible Barriers,” and “Leadership Gendered as Male” by Jane Forbes in “The Sociology of Gender” [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: collapsing three sections into two sections; editing for brevity.

Figure 13.16 Chart by Statista Research Department is in the Public domain.

Figure 13.17 Photo by WOCinTech is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

“Working Parents Face Additional Barriers” adapted from “Pay Discrepancies” and “Pay Discrimination” by Jane Forbes in “The Sociology of Gender” [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: combining two sections with a focus on parenting.

Figure 13.18 Chart by United States Census Bureau in the Public domain.

References

Bradwell v. The State, 83 U.S. 130 (1873)

Brandford, A., & Brandford-Stevenson, A. (2021). Going up!: Exploring the phenomenon of the glass escalator in nursing. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 45(4), 295-301. doi:10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000489.

Buchholz, K. (2022). How Has the Number of Female CEOs in Fortune 500 Companies Changed Over the Last 20 Years? Weforum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/ceos-fortune-500-companies-female.

Fanning, N. L. (2019, April 10). I thought I could serve as an openly gay man in the army. Then came the death threats. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/10/magazine/lgbt-military-army.html

Gomez, L. E., & Bernet, P. (2019). Diversity improves performance and outcomes. Journal of the National Medical Association, 111(4), 383-392. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2019.01.006.

Heggeness, M. (2020, October 26). Why is mommy so stressed? Estimating the immediate impact of the covid-19 shock on parental attachment to the labor market and the double bind of mothers | opportunity & inclusive growth institute (Institute working paper #33). Minneapolis Federal Reserve. https://www.minneapolisfed.org:443/research/institute-working-papers/why-is-mommy-so-stressed-estimating-the-immediate-impact-of-the-covid-19-shock-on-parental-attachment-to-the-labor-market-and-the-double-bind-of-mothers

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Anafi, M. (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality. https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf

Kagan, J. (2022, December 7). Glass cliff. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/g/glass-cliff.asp

Koval, C. Z., & Rosette, A. S. (2021). The natural hair bias in job recruitment. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 741-750. doi:10.1177/1948550620937937.

Lendon, B., Blake, E., & Josuka, E. (2022, May 16). First Woman to Command U.S. Aircraft Carrier Didn’t Even Know She Could Get the Job. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/05/16/asia/us-navy-woman-aircraft-carrier-commander-intl-hnk-ml/index.html

Miller, S. (2022, March 15). Gender Pay Gap Improvement Slowed During the Pandemic. SHRM. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/compensation/pages/gender-pay-gap-improvement-slowed-during-the-pandemic.aspx

Milli, J., Frye, J. & Buchanan, M. J. (2022). Black Women Need Access to Paid Family and Medical Leave. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/black-women-need-access-to-paid-family-and-medical-leave/

Payscale. (n.d.). 2023 Gender Pay Gap Report. https://www.payscale.com/research-and-insights/gender-pay-gap/

Sear, K. & Goldstein D. (2021, January 29). Analysis: Pregnancy Bias Suits Keep Rising Amid Pandemic. Bloomberg Law. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/bloomberg-law-analysis/analysis-pregnancy-bias-suits-keep-rising-amid-pandemic/

Sweet, J. (2021, October 5). History of Women in the Workplace. Stacker. https://stacker.com/stories/4393/history-women-workplace

U. S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Access to and Use of Paid Family and Medical Leave: Evidence from Four Nationally Representative Datasets. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2019/article/racial-and-ethnic-disparities-in-access-to-and-use-of-paid-family-and-medical-leave.htm

U. S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021) Women in the Labor Force: A Databook.” https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-databook/2020/home.htm