1.3 A Historical Context for Today’s Families

Once upon a time, single-parent and same-sex families did not exist, or so the popular television shows and movies of past decades would have us believe. Neither did interracial couples, mothers working outside the home, couples deciding not to have children, or other family forms and situations that are increasingly common today. Domestic violence and child abuse were not widely discussed or acknowledged publicly. However, other family forms and situations also existed then, though they have become more visible, more accepted, and perhaps more common today.

The “Nostalgia Trap”

In contrast to idealized images of the past, we now hear that parents are too busy working at their jobs to raise their kids properly. We hear of kids living without fathers because their parents either are divorced or were never married in the first place. We hear of young people having babies, using drugs, or committing violence.

We hear that the breakdown of the nuclear family, the entrance of women into the labor force, and the growth of single-parent households are responsible for these problems. Some observers urge women to work only part-time or not at all so they can spend more time with their children. Some yearn wistfully for a return to the 1950s, when everything seemed so much better and easier. Children had what they needed back then: one parent to earn the money and another parent to take care of them full time until they started kindergarten, when this parent would be there for them when they came home from school.

Families have indeed changed, but this yearning for the 1950s falls into the “nostalgia trap” (Coontz, 2000). The 1950s television shows did depict what some families were like back then, but they failed to show what many other families were like. Moreover, the changes in families since that time have probably not had the harmful effects that many observers allege. It is more likely that the challenges that many families face today have more to do with economic change; increasing levels of poverty; and systemic racism, sexism, and other “isms.”

Much of this text focuses on uncovering systemic forces that interact with family life. In fact, historical and cross-cultural evidence suggests that the Leave It to Beaver–style family of the 1950s was a relatively recent and atypical phenomenon and that, given equitable access to resources, many other types of families can thrive just as well as those 1950s television families did.

Defining Family

Many family forms exist in the United States and throughout the world. When we try to define the word “family,” we realize just how slippery of a concept it is.

The dominant ideology of what constitutes a family in the United States was a very class- and race-specific type of gendered family formation (Figure 1.12). This family formation has been labeled the Standard North American Family (SNAF) and is defined as:

A conception of the family as a legally married couple sharing a household. The adult male is in paid employment; his earnings provide the economic basis of the family-household. The adult female may also earn an income, but her primary responsibility is to the care of the husband, household, and children. Adult male and female may be parents (in whatever legal sense) of children also resident in the household (Smith 1993).

Figure 1.12. Defining families with a “family ideal” is harmful to other families and to the social structure that supports families.

When we put the SNAF into a historical perspective, we are able to see how this dominant family formation is neither natural nor outside of the politics and processes of race, class, and gender inequality. The SNAF originated in the 19th century with the separation between work and family, and it was occasioned by the rise of industrial capitalism (Cott, 2000; Coontz, 2005).

While it can be desirable to develop criteria for a definition, these criteria deny the importance and existence of many kinship formations such as single parents, stepparents, extended family, and other kinship relationships. It also excludes what Kath Weston (1991) has labeled “chosen families,” or how queer people who are ostracized from their families of origin form kinship ties with close friends. The diversity of family formations across time and place tells us that the definition of a “family” tends to favor specific traits and devalue others. It reproduces an ideology of “the family” that obscures the diversity and reality of family experiences (Gerstel, 2003).

Traditional definitions of families also exclude those who consider each other family but cannot or do not live in the same household, often for economic reasons. This includes transnational families—for example, South or Central American parents leaving their country of origin to make wages in the United States and send them back to their families. Transnational families are common in the United States, partly because immigration laws have historically limited immigration to people who can obtain employment, and families are divided temporarily or permanently. The Great Recession (2009 to 2014) also separated families who had been living together in the United States, sometimes across the country and sometimes between nations.

Other families who live apart also include families with a member who is incarcerated. People who are imprisoned represent a significant portion of the population in the United States. Although the rate of prison incarceration has slowly been falling since 2008, the United States incarcerates a larger share of its own population than any other country (Gramlich, 2021).

This population includes parents: “Parents held in the nation’s prisons—52 percent of state inmates and 63 percent of federal inmates—reported having…minor children, accounting for 2.3 percent of the U.S. resident population under age 18” (Sabol & West, 2010). That means that more than 2% of children in the United States have a parent incarcerated.

Preindustrial Period

The industrial economy evolved in the United States between 1750 and 1850. Prior to an economy based on the creation of commodities in urban factories, the family was primarily an agricultural work unit—there was no separation between work and home. People in foraging societies, sometimes called hunter-gatherer groups, probably lived in small groups composed of several nuclear families. These groupings helped ensure that enough food would be found for everyone to eat.

While men tended to hunt and women tended to gather food and take care of the children, both sexes’ activities were considered equally important for a family’s survival. Many Native American societies during this time were even matriarchal in nature.

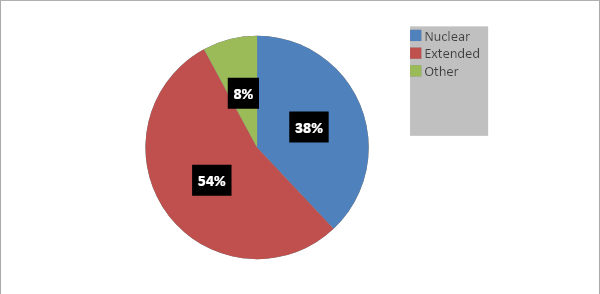

Plant food and livestock were abundant, and families’ wealth and well-being depended on fertile land and the size of herds. Because men were more involved than women in herding, they acquired more authority in families, and families became more patriarchal than previously (Quale, 1992). Still, families continued to be the primary economic unit of society until industrialization. Colonization of Indigenous people altered family structure via the emphasis on patriarchy. The nuclear family that was so popular on television shows during the 1950s was much less common during the preindustrial period (Figure 1.13).

Figure 1.13. This graph shows the main kinds of families in preindustrial societies. Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

Colonization refers to two structural activities in the United States. The first was the colonization of North America by European countries attempting to increase their power and wealth. This period ended with the incorporation of the 13 existing colonies into the United States of America following the American Revolutionary War, sometimes called the War for Independence, which ended in 1783.

Colonization also refers to the actions that the colonies and then the newly incorporated states took to increase their power, influence, and wealth. This included moving Native Americans off of their homelands to less fertile areas and creating boarding schools for their children that broke up families and destroyed Indigenous languages and culture. In addition, colonists enslaved African people who were brought to this country against their will, treating them as objects and separating families.

During this time, nomadic Native American groups had relatively small nuclear families, while groups that were more stationary had larger extended families; in either type of society, however, “a much larger network of marital alliances and kin obligations [meant that] no single family was forced to go it alone” (Coontz, 1995). The U.S. institution of legalized slavery, which lasted from the country’s founding until 1865, made it difficult for enslaved African Americans to maintain nuclear families. Enslavers frequently sold children and broke apart families to increase their profits. Enslaved people adapted by developing extended families, adopting orphans, and taking in other people not related by blood or marriage.

Industrialization

With the rise of industrial capitalism between 1750 and 1850, working-class families and families of color (who had been denied access to union jobs or were still enslaved) needed to have all the adults and children go to work. The majority of family members—including children and women—worked in factories or domestic labor, serving middle-class and wealthy families.

Middle-class families who had inherited property and wealth—the vast majority of whom were White—did not need all the members of their families to work. They were able to pay for their homes; hire house servants, maids (who were primarily African American or immigrant women of color), and tutors; and send their children to private educational institutions with the salary of the breadwinning father, who provided the financial means for himself and his family. Also sometimes referred to as “family-wage jobs,” jobs that could support an entire family were more common during this time period than they are now.

Thus, the gendered division of labor—wherein women perform unpaid care work within the home and men are salaried or wage-earning breadwinners—that is sometimes assumed to be a logical organization of family life is a relatively recent economic invention that privileged middle-class White families. In these families, women stayed at home to take care of children and do household chores and were paid nothing (Gottlieb, 1993). For this reason, men’s incomes increased their patriarchal hold over their families.

In poor, immigrant, and many Black families, women continued to work outside the home. Because families now had to buy much of their food and other products instead of producing them themselves, the standard of living actually declined for many families.

This false split between the publicly oriented working father and the privately oriented domestic mother produced the ideologies of separate spheres and the cult of domesticity, which celebrated women’s roles as mothers and homemakers. The ideology of separate spheres held that women and men were distinctly different creatures with different natures and therefore suited for different activities. Masculinity was equated with breadwinning, and femininity was equated with homemaking (Figure 1.14).

Figure 1.14. The idealized White middle-class woman equated domesticity with femininity but failed to account for the poor, immigrant, Black, or other marginalized people who were most often servants or helpers in middle-class homes.

Likewise, the cult of domesticity was an ideology about White womanhood that held that White women were asexual, pure, moral beings properly located in the private sphere of the household. Importantly, this ideology was applied to all women as a measure of womanhood. The effects of this ideology were to systematically deny working-class White women and women of color access to the category of “woman” because they had to work and earn wages to support their families.

Furthermore, during this period, coverture laws legally defined White married women as the property of their husbands. Upon marriage, a woman’s legal personhood was dissolved into that of the husband. They could not own property or sign or make legal documents, and any wages they made had to be turned over to their husbands. Thus, even though they did not have to work in factories or the fields of plantations, White middle-class women were systematically denied rights and personhood under coverture. In this way, White middle-class women had a degree of material wealth and symbolic status as pure, moral beings, but it came at the cost of their legal personhood.

Early and Mid-20th Century

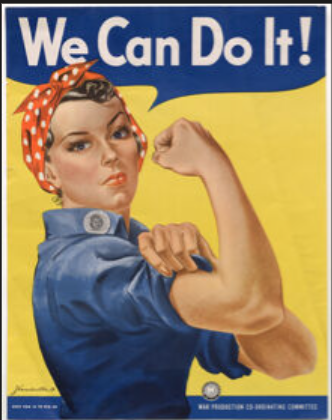

Medical, automotive, and technical advances led to many women entering the workforce in the 1920s, primarily in office jobs, and the Great Depression of the 1930s led even more women to work outside the home. During the 1940s, a shortage of men in shipyards, factories, and other workplaces because of World War II led to a national call for women to join the labor force to support the war effort and the national economy. They did so in large numbers, and many continued to work after the war ended. One of the most iconic images from this period is Rosie the Riveter, which came from an ad campaign to recruit women into defense industry jobs during the war (Figure 1.15).

Figure 1.15. This popular poster exemplifies the power that women experienced and demonstrated during World War II.

But as men came home from Europe and Japan, books, magazines, and newspapers exhorted women to have babies, and babies they did have: people got married at younger ages, and the birth rate soared, resulting in the now-famous Baby Boom generation. Meanwhile, divorce rates dropped. The national economy thrived as automotive and other factory jobs multiplied, and many families for the first time could own their own homes. Suburbs sprang up, and (mostly White) middle-class families—moved to them; they did indeed fit the Leave It to Beaver model of the breadwinner-homemaker suburban nuclear family (Skolnick, 1991).

Even so, less than 60% of American children during the 1950s lived in these breadwinner-homemaker nuclear families (Coontz, 2000). Teenage pregnancy rates were about twice as high as today, although more pregnant teens were already married or decided to get married because of the pregnancy. Although not as publicly acknowledged back then, alcoholism and violence in families were present. Historians have found that many women in this era were unhappy with their homemaker roles, chafing against what would come to be called the “feminine mystique”—the idea that women could and should be satisfied in the roles of wife, homemaker, and mother (Friedan, 1963).

In the 1970s, the economy finally worsened. Home prices and college tuition soared much faster than family incomes, and women began to enter the labor force as much out of economic necessity as out of simple desire for fulfillment. More than 60% of married women with children under six years of age were in the labor force, compared to less than 19% in 1960 (Coontz, 1997). Working mothers were no longer a rarity.

Postmodernism emerged as a theory that explains changing behavior in the late 20th century. The postmodern theory emphasizes individuality and choice. When this is applied to family life, we can see that the majority of families in the United States now do not fit into one particular structure. The multiple and numerous differences in the ways in which people structure their families today can be called postmodern families (Stacey, 1998).

The highly gendered nuclear family model popularized in the 1950s must be considered a blip in U.S. history rather than a long-term model. At least up to the beginning of industrialization and, for many families after industrialization, women as well as men worked to sustain the family. “American families always have been diverse, and the male breadwinner-female homemaker, nuclear ideal that most people associate with ‘the’ traditional family has predominated for only a small portion of our history” (Coontz, 1995). It can be said that rather than thinking of the 1950s as the last era of family normality, it is actually the 1950s that deviate from the norm of diverse families over time (Skolnick, 1991).

How Policies Define Family

The dominant historical ideology of the SNAF is reinforced by present-day law and social policy. For example, when gay men and lesbians have children, they often rely on adoption or assisted reproductive technologies, including in vitro fertilization or surrogacy (where a woman is contracted to carry a child to term for someone else), among other methods. Because laws in most states assume that blood ties between mother and child supersede non-biological family relations, gay men and lesbians who seek to have children and families face barriers to legal parenthood.

Social policies often assume not only that the nuclear heterosexual family is a superior family structure but also that its promotion is a substitute for policies that would seek to reduce poverty. For instance, both the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama promoted marriage and the nuclear family as a poverty reduction policy. These programs have targeted poor families of color in particular. In the Healthy Marriages Initiative of 2004, President Bush pledged $1.5 billion to programs aimed at “marriage education, marriage skills training, public advertising campaigns, high school education on the value of marriage and marriage mentoring programs…[and] activities promoting fatherhood, such as counseling, mentoring, marriage education, enhancing relationship skills, parenting, and activities to foster economic stability” (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2009).

Such policies ignore the historical structural sources of racialized poverty and blame the victims of systemic classism and racism for problems that they did not create. As the history of the SNAF shows, the normative family model is based on a White middle-class model—one that a majority of families in the United States do not fit.

Licenses and Attributions for A Historical Context for Today’s Families

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The ‘Nostalgia Trap’” is adapted from “Social Issues in the News” in Exploring our Social World: The Story of Us by Jean Ramirez, Rudy Hernandez, Aliza Robison, Pamela Smith, and Willie Davis. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: rewritten for clarity.

“Defining Family” is adapted from “The Family” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, and Laura Heston, UMass Amherst Libraries. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: original expansions; also content remixed from Defining the Family in Exploring our Social World: The Story of Us by Jean Ramirez, Rudy Hernandez, Aliza Robison, Pamela Smith, and Willie Davis. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

“Early and Mid-20th Century” is adapted from Defining the Family in Exploring our Social World: The Story of Us by Jean Ramirez, Rudy Hernandez, Aliza Robison, Pamela Smith, and Willie Davis. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: decolonizing; addition of postmodernism; and small edits.

“Family and Policy” is adapted from “The Family” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, and Laura Heston, UMass Amherst Libraries. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: decolonizing; small edits.

Figure 1.12. “Family Ideal” by bykst is in the Public Domain, CC0.

Figure 1.13. “Types of Families in Preindustrial Societies” is from Defining the Family in Exploring our Social World: The Story of Us by Jean Ramirez, Rudy Hernandez, Aliza Robison, Pamela Smith, and Willie Davis. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.14. This work by ArtsyBee is in the Public Domain, CC0.

Figure 1.15. “Rosie the Riveter” is by the National Archives Catalog from https://catalog.archives.gov/id/535413 and is unrestricted in the public domain.

References

Coontz, S. (2000). The way we never were: American families and the nostalgia trap. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Coontz, S. (1997). The way we really are: Coming to terms with America’s changing families. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Coontz, S. (1995, Summer). The way we weren’t: The myth and reality of the “traditional” family. National Forum: The Phi Kappa Phi Journal, 11–14.

Cott, N. (2000). Public Vows: A History of Marriage and the Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Friedan, B. (1963). The feminine mystique. New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Gerstel, N. 2003. “Family” in The Blackwell Dictionary of Modern Social Thought, edited by W. Outhwaite. Blackwell Publishing, Ltd.

Gottlieb, B. (1993). The family in the Western world from the Black Death to the industrial age. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Gramlich, J. (2021). America’s incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995/

Quale, G. R. (1992). Families in context: A world history of population. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Sabol, W. & H.C. West. 2010. Prisoners in 2009. NCJ 231675. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Skolnick, A. (1991). Embattled paradise: The American family in an age of uncertainty.

Smith, D. 1993. “The Standard North American Family: SNAF as an ideological code.” Journal of Family Issues 14(1): 50-65.

Stacey, J. (1998). Brave New Families, University of California Press.

Weston, K. 1991. Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

United States Census Bureau. QuickFacts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045216/00.