1.5 The U.S. Government and Families

One of the most (if not the most) powerful social institutions in the United States is the government. It is important to note that in the United States, the federal government has three branches: legislative (Congress), executive (the president), and judicial (the court system). In addition, the Constitution recognizes the rights and responsibilities of state governments; counties and cities have governing structures as well. All of these structures legislate in ways that affect families, some directly and some indirectly. The United States is considered to be a “common law” country, meaning that laws are derived in three ways: legislation created by governing bodies; administrative rules and regulations; and decisions via judicial courts.

Family Formation and the Law

Most family law (including marriage, divorce, and adoption) is governed by the states. When there is a great deal of advocacy, unrest, inequity, or controversy, family-related matters rise to the federal level. Here are two examples:

-

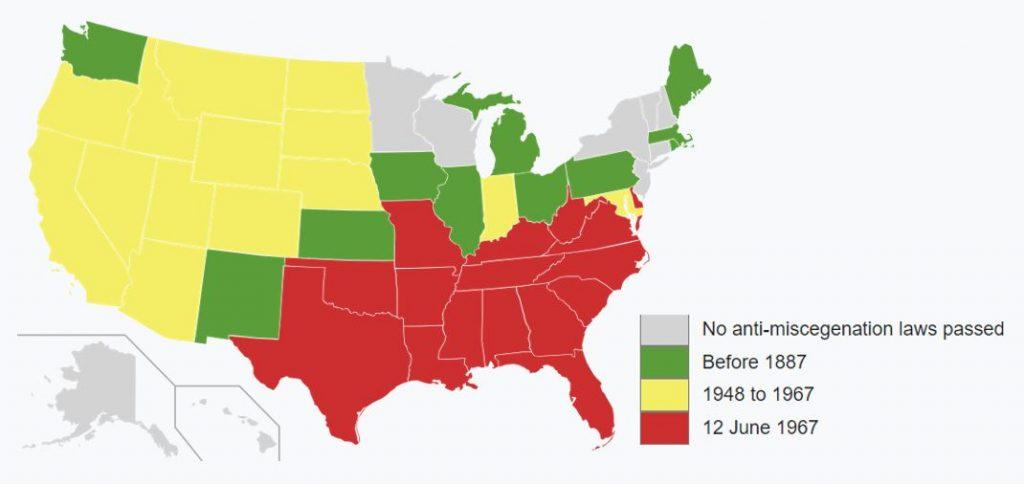

In 1958, Mildred Loving, a woman of color, and Richard Loving, her White husband, were sentenced to a year of prison for marrying each other, breaking Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which supported the now-outdated idea that separate races exist and that interbreeding (miscegenation) is problematic. The Lovings appealed their conviction in Virginia and eventually to the U.S. Supreme Court, who ruled in 1967 (Loving v. Virginia) that all laws banning interracial marriage were violations of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which made it illegal for individual states to restrict interracial marriage (Figure 1.23).

Figure 1.23. Dates of repeal of U.S. anti-miscegenation laws by state.

-

More recently, the ruling on Loving v. Virginia has been utilized to argue that laws banning same-sex marriages were also unconstitutional. Between 2012 and 2014, plaintiffs from multiple states filed in state courts to overturn state laws that criminalized same-sex marriages (Figure 1.24). While several district courts found these laws to be unconstitutional, one district court ruled in favor of the constitutionality of these laws. With the split between courts, the case rose to the level of the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 2015 that all states must perform and recognize marriages between same-sex couples (Obergefell v. Hodges).

Figure 1.24. In 2015, the U.S. Supreme Court decided, by a narrow margin, to legalize same-sex marriage.

Of note is that while the 1967 decision to legalize interracial marriage was a unanimous decision, the 2015 decision to legalize same-sex marriage was closely contested among the U.S. Supreme Court justices and passed by a narrow 5–4 margin. It appears that there is still disagreement among the most powerful in this country about whether the language in the Fourteenth Amendment applies to marriage, gay and lesbian people, or neither. The amendment states in part: “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” How would you interpret the differentiated results of these decisions?

From Loving v. Virginia (1967) and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), we can derive some understanding that governments influence whom we marry; how we divorce; and the legal relationships, rights, benefits, and taxes related to parenting, kinship structures, and children (Figure 1.25). Critically, we must note that the government places value on socially constructed differences such as race, ethnicity, and sexuality in ways that impact individual and family choice.

Figure 1.25. While we may take for granted the rights of interracial couples to marry (like John Legend, who is Black, and Chrissy Teigen, who is Thai and White), this right is only guaranteed through the 1967 U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

Laws are only one of the ways that government impacts family composition. Consider the federal government’s role in taxing individuals and families and then redistributing that money via benefits. Benefits such as food stamps, Temporary Aid for Needy Families (TANF), K–12 school lunches, and financial aid for college are all distributed and regulated by the government. Tax credits, such as the Child and Dependent Care Credit, are driven by the government’s definition related to that specific tax. Specifically, the government’s definitions of eligibility and family structure impact who receives benefits and how much they receive.

If the government defines “family” or “dependent” in a specific way, does that impact how families form? For example, college financial aid does not count the income of a roommate or domestic partner in an applicant’s income, but it does count the income of a spouse. Might this influence a college student’s decision to marry? While this union is not criminalized as the previous two examples were, it is still impacted by the government’s criteria related to distributing benefits. Some of us might decide to marry or not to marry based on the federal government’s criteria for benefits or taxes.

Family Residence and Kinship Structure

While co-residence is considered by many family theorists to be a pillar of the definition of family, it is important to note that not all families live together. In fact, the U.S. government has played a role in separating family members from one another (immigrant and enslaved families in particular).

Sometimes the United States has been idealized as a “melting pot” or a “salad bowl” of cultures and ethnicities. Many immigrate to this country to make a better life for themselves and their families. The borders of the United States were open until the late 1800s, when the first restrictive immigration law was enacted: the Page Act of 1875, which excluded Chinese women. This act specifically targeted Chinese workers who were providing needed labor in gold mines and agriculture and, most notably, building the transcontinental railroad (Figure 1.26). The Page Act was intended to discourage Chinese laborers from staying in the United States by separating them from their wives and families.

Figure 1.26. Since 1882, numerous U.S. immigration laws have targeted people from Asian and Latin American countries.

By 1882, Chinese men were excluded as well. Since that time, there have been numerous restrictive versions of immigration laws in the United States, most of them targeting people from Asian and Latin American countries. In combination with these laws, the United States has continued to rely on immigrant labor to perform less desirable and lower-paying jobs, specifically in agriculture, sanitation, service, and cleaning. There will be more discussion of the effects on these families in Chapters 7, 8, and 10. Restrictive immigration laws and policies have contributed to the formation of involuntary transnational families, or families whose members live on different continents and/or in different countries.

Another related idealization of the United States originates in the Declaration of Independence, which states, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness” (Jefferson et al., 1776). It is difficult to defend equality as a fundamental right, both when the document was written and today as well. The most obvious example is the enslavement of people from Africa, who were intentionally imprisoned and brought to this country; even when freed, they continued to have legally limited rights. Women were excluded from land ownership, voting, and being able to file for divorce. The U.S.government specifically secured the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for one group of people (Euro-American males); enslaved another group (African Americans); and used legal means to oppress Native Americans, women, and immigrants.

Slavery dramatically affected family formations and kinship structures. Because human beings were considered property, their family ties were disregarded, which meant that children were habitually separated from parents, adults were not able to marry at will, and common-law spouses were removed from one another at the will of the enslaver. Violence against women in the form of rape resulted in parenting relationships that were structured and controlled by the enslavers.

There is continued discussion about the effects on families who have descended from enslaved people. While families were forcibly separated, there was resistance to the severance of family ties. For example, children taken from their birth parents and sold were often assigned to adults in caregiving relationships. People forced together created families and used kin names such as “aunt,” “uncle,” and “cousin” to delineate familial relationships. Because enslaved people were often thrown in together with others who came from all over Africa with differing customs and traditions, it is difficult to know which family practices that survived came from original traditions and which came from active resistance to the disruption of their biological and chosen families (Taylor, 2000).

Both free and enslaved African Americans played active roles during the American Revolution and the writing of the Declaration of Independence. About 20% of enslaved people escaped and sought sanctuary among Native Americans or the British during the war. Many fought in the war, including Private Lemuel Haynes, who believed that the revolution should also be a war against slavery. He rebutted the Declaration of Independence, saying the document’s principle of freedom should put an end to slavery. Thousands of Black fighters for freedom participated in the emancipation of the United States from Britain (Ortiz, 2018).

In Focus: What We Teach in School Affects Family Identity and Structure

Dean Spade is a lawyer, writer, trans activist, and associate professor of law at the Seattle University School of Law. He grew up with a single mother and in foster homes. He is known for his work with transgender, intersex, and gender nonconforming people who are low income and/or people of color. He founded a nonprofit law collective that provides free legal services to members of these groups. He writes critically about intersectionality, historical records, and the limits of law in Normal Life:

Social movements engaged in resistance have given us a very different portrayal of the United States than what is taught in most elementary school classrooms and textbooks. The patriotic narrative delivered at school tells us a few key lies about U.S. law and politics: that the United States is a democracy in which law and policy derive from what majority of people think is best, that the United States used to be racist and sexist but is now fair and neutral thanks to changes in the law, and that if particular groups experience harm, they can appeal to the law for protection.

Social movements have challenged this narrative, identifying the United States as a settler colony and a racial project, founded and built through genocide and enslavement. They have shown that the United States has always had laws that arrange people through categories of indigeneity, race, gender, ability, and national origin to produce populations with different levels of vulnerability to economic exploitation, violence, and poverty (Spade, 2015).

Figure 1.27. Dean Spade has been named one of the “50 Visionaries Who are Changing Your World”.

Spade reminds us that as long as we continue to teach children without using a truthful and critical lens on our past, we will continue to reinforce the differences constructed by government and society.

Licenses and Attributions for The U.S. Government and Families

Open Content, Original

“The U.S. Government and Families” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: What We Teach in School Affects Family Identity and Structure” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.23. “Dates of Repeal of U.S. Anti-Miscegenation Laws by State” by Certes. License: CC BY 3.0. Modification: moved key closer to image.

Figure 1.24. Photo 1401430 on px.here and is in the public domain under CC0.

Figure 1.25. “146030_3994” by Walt Disney Television. License: CC BY-ND 2.0.

Figure 1.26. “Chinese Miners Idaho Springs” by Dr. James Underhill. Public domain.

Figure 1.27. “Dean Spade on the Laura Flanders Show in 2015” by The Laura Flanders Show. License: CC BY 3.0.

References

Jefferson, T., et al. (1776, July 4). The declaration of independence [transcription]. National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

Ortiz, P. (2018). An African American and Latinx history of the United States. Beacon Press.

Spade, D. (2015). Normal life: Administrative violence, critical trans politics, and the limits of law (Revised and expanded edition). Duke University Press.

Taylor, Ronald L. 2000. “Diversity within African American Families.” In Handbook of Family Diversity, edited by David H. Demo, Katherine R. Allen, and Mark A. Fine, pp. 232–251. New York: Oxford University Press.