13.5 Care Work

What do you consider work? Do you consider work as loading and running the dishwasher before catching a train on the subway? What about washing a load of laundry after an eight-hour restaurant server shift? Calling the doctor to make an appointment for your sick child? It is the mundane everyday activities such as shopping for groceries, making meals, scheduling appointments and play dates, cleaning the bathrooms, and various other tasks that make households that are less often viewed as official work. This kind of work is called care work, the daily work that keeps a household running, and the adults and children well cared for.

When care work is performed by someone who also is working outside of the home, it is called the second shift, coined by researcher Arlie Hochschild. She found that women are more likely than men to perform work inside the home in addition to working outside the home (Hochschild, 1990). The balance of household responsibility has changed as companies recognize the need for employee-life balance, cultural acceptance of stay-at-home dads, and the growing egalitarian ideologies between partners but women still have a longer second shift (Blair-Loy, 2015).

Shifting family dynamics due to re-partnering, marriage, divorce, or death create unique challenges for all families experiencing these significant transitions. Expectations of chore responsibilities inside the home may vary for members who live across multiple residences. Differing household rules or strained relationships with new family members can cause household conflict. The concept of boundary ambiguity helps us understand that not all families, and thus their expectations for household work, are the same. Boundary ambiguity “is defined as the family not knowing who is in and who is out of the system” (Boss and Greenberg 1984:535). This idea encompasses physical and psychological presence or absence, as graphically presented in Figure 13.19.

Figure 13.19. For many children and adults, changing family structures can bring about boundary ambiguity, meaning it’s not always clear who is part of a family and what the expectations are for a person’s role in the family. Transgender and gay relationships create unique challenges for households. When gay male families where one partner was the children’s biological father were studied, boundary ambiguity was highlighted due to institutional factors such as “heterosexism, legal decisions, and beliefs and practices encouraged in religious institutions” (Jenkins, 2013) as well as interpersonal factors such as “the relationship of the gay parent with his ex-spouse and children” (Jenkins, 2013).

Lack of Childcare and Eldercare

Appearance and behavioral standards are not the only workplace barrier for employees. Workers may be responsible for taking care of children or other adults. Lack of childcare or caring for an elderly person creates physical and emotional strain for many workers. Women have long been considered to have natural, internal instincts for raising children. Such expectations can create barriers for women in the workplace when they are expected to be the primary caregiver, although, for many families, they are not. Research has shown concerns for children’s care while at work cause increased stress. Caregiving for children or the elderly is stressful and takes an emotional toll on the caregiver. Negative health outcomes for caregivers exist for all gender caregivers, yet women take on a disproportionate amount of caregiving globally (Sharma et al., 2016).

Finding and affording childcare became an increasing concern for low-wage workers through the late 20th century as more women gained full-time employment. Although the percentage of women in the workplace peaked in the late 1990s, the need for safe, affordable childcare and eldercare persists today.

Data from late 2020, about six months after the COVID-19 pandemic, showed childcare as an increasing problem for all gender parents. With many schools closed then, women were more likely than men to express increased responsibilities and difficulties balancing work and childcare responsibilities. (Schaeffer, 2022). By June 2021, another study found that “Globally, women took on 173 additional hours of unpaid childcare last year, compared to 59 additional hours for men.” (Avi-Yonah, 2021). This is nothing new, as women have traditionally assumed responsibility for the care of family members.

In Focus: Pandemic Parenting

The pandemic has affected parents, especially mothers, in the paid workforce. The transition to online schooling and stay-at-home orders during the coronavirus pandemic required at least one adult in the home to focus on the children—helping them with schoolwork and supervising them all day.

While there was no immediate impact on detachment or unemployment, working mothers in states with early stay-at-home orders and school closures were 68.8% more likely to take leave from their jobs than working mothers in states where closures happened later, according to new research by the U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve (Heggeness, 2020). While one study found that dads increased their childcare role during the pandemic, it also showed moms spent the most time caring for children (Sevilla & Smith, 2020).

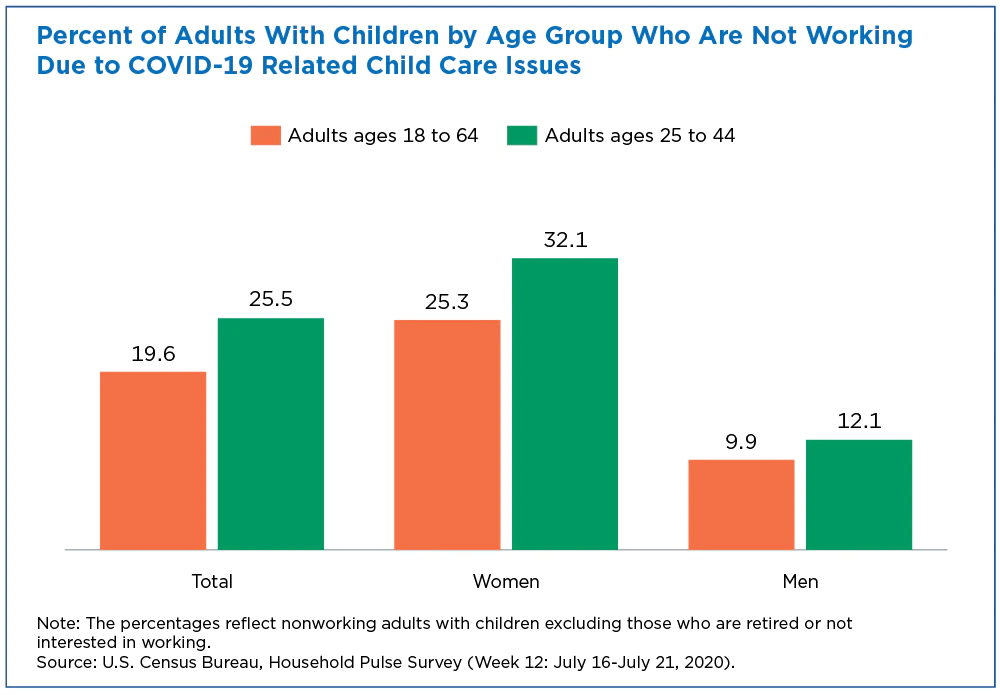

In the United States, around one in five (19.6%) of working-age adults said the reason they were not working was because COVID-19 disrupted their childcare arrangements as shown in Figure 13.20.

Figure 13.20. This graph shows that in two different age groups (18 to 64 years and 25 to 44 years), the percentage of women who are not working specifically due to COVID-19 childcare issues is much higher than it is for men.

Eldercare is another barrier many women face in the workplace. As women’s careers progress, they are also unequally responsible for the care of aging parents. Known as the sandwich generation, people who support the needs of their children and parents simultaneously can find these responsibilities strain finances, time, and work commitments. As women’s roles in the workplace have become more socially normed over the last 30 years, men’s participation as caregivers for elderly relatives has increased. One study found that “women who cared for ill parents were twice as likely to suffer from depressive or anxious symptoms as non-caregivers” (National Center on Caregiving at Family Caregiver Alliance, 2003). As the primary caregivers for elderly parents and relatives, women’s health is negatively impacted, yet many report positive emotional benefits to this role as shown in Figure 13.21.

Figure 13.21. Senior people have a lifetime of experiences to share with young people.

Low-income, typically people of color, and single heads of households, which are historically predominantly women, face intensified childcare and eldercare burdens due to ever-increasing costs. Recent data shows that “Oregon is ranked 14th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia for most expensive infant care” (Economic Policy Institute, 2020). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which studies these trends, recognizes affordable care as “no more than 7% of a family’s income” yet “Infant care for one child would take up 22.2% of a median family’s income in Oregon” (Economic Policy Institute, 2020). When faced with childcare challenges, men who are single heads of households are more likely to be able to adjust their work responsibilities to accommodate childcare needs.

Making childcare more affordable and accessible to all families is important, especially for single parents. This means women in particular can be more stable employees, excel in the workplace, and build wealth over time. It also reduces the cycle of poverty for single-parent families. Support networks do exist for all gender caregivers. Private and public agencies can help with emotional and physical support. They can also help with financial advice and resources as workers stuck in low-wage positions find it difficult to move out of poverty when faced with ever-increasing childcare costs.

Emotional Labor and Kin-Keeping

Interactions with the public or customers are common across most workplaces. Many companies have written expectations for how they expect workers to perform their roles and provide a detailed script to employees. Employees may find themselves performing emotional labor when interacting with customers. Workers who perform emotional labor hide their emotions in the workplace to ensure a pleasant and consistent customer experience. Females dominate jobs with emotional labor such as education and health care industries where there are frequent interactions with customers.

In addition, women traditionally have taken on the highly emotional roles of childcare and eldercare providers more often than men. And even when they don’t, society often implicitly assumes that they will. It follows that women are more likely than men to perform relationship-building functions within families. The effort to build and maintain relationships between family members is called kin-keeping and is a part of care work.

Although kin-keeping increases the likelihood of stress due to role conflict between obligations at work and at home, especially for women, kin-keeping can have positive benefits (Gerstel & Gallagher, 1993). One study looked at African American grandmothers caring for their grandchildren. Interactions with grandchildren positively impacted the grandmothers’ workplace readiness. An additional benefit was that grandmothers’ workplace experiences could be shared with grandchildren (Stephens, 2019).

In Focus: Gendered Work Expectations, Taxes, and Family Wealth

Income taxes and social security are heavily dependent on the institutional marriage of the mid-20th century, specifically the breadwinner-homemaker model. Couples were more homogeneous at that time; likely to marry early and stay married longer, with men typically earning more or much of the income. Both the federal income tax system and the social security system evolved over the 20th century to correct what was considered to be the most common gender injustice: that many women made less money than their spouses (Figure 3.22).

These systems failed to take into account the racial injustice of the times; when social security was implemented in 1935 it excluded all domestic and farm workers who were primarily Black people and immigrants. Both groups were added in the 1950s.

Figure 13.22. Although union formations are more diverse today, many government benefits and tax systems are based on a specific model of marriage.

Much has been discussed about the “marriage bonus” and the “marriage penalty,” meaning that some couples benefit from marrying and some couples pay more taxes when they marry. The federal and state systems have changed over the years but face what is called a “trilemma” by tax experts: systems cannot simultaneously impose progressive marginal tax rates, assess equal taxes on married couples with equal earnings, and maintain marriage neutrality (meaning that married and unmarried couples pay the same amount of taxes). The net result from the trilemma is that married couples whose individual incomes are comparable pay more in taxes than a couple whose incomes are dramatically different (Alstott, 2013).

Both social security, with its emphasis on survivor benefits, and income taxes focus on the marriage ideal from the last century: one spouse (usually male) who earns most of the family’s income and a lower-earning spouse (usually female). But this has not been the norm for over 50 years, and many argue that these systems need to catch up. As explained by the postmodern theory, choice and individuality are emphasized in today’s society. Diverse relationships are accepted more readily, and marriages are less assortative in most ways. Marriage is declining; people wait longer to marry, are less likely to marry, and stay married for fewer years. Couples are more likely to have equal rather than disparate individual incomes. All of these factors point to the inadequacy of the current systems and raise the question of whether these policies influence people’s choice to marry or otherwise partner up.

Caregivers at Home, Caregivers at Work

Working parents in all fields face the challenge and stress of balancing their work lives with caring for their children, as well as other personal and household responsibilities. In this section we will focus on a subset of working parents who have elected to work in jobs or careers that are focused on serving others. These fields include education, health, human services, and hospitality.

In all of these fields there is an emphasis on serving others and to some degree a focus on a cause greater than oneself. For example, teachers are focused on creating a curriculum and an environment in which students achieve specific learning outcomes. At the same time, they are concerned with their students’ overall well-being. They work with 25 to 150 students each year, depending on their teaching assignments, with a societal expectation that all of these students will succeed.

How does being service oriented in one’s work life overlap with nurturing when also a parent?

It is undeniable that the collapse of many public systems during the pandemic affected this group of caregivers powerfully, putting many of them in a public bind. Teachers who are caregivers at home faced both the immediate need to completely adapt their curriculum into online and video conferencing content at the same time, arranging for their own children or dependents to adjust to lack of in-person services. Many times they were teaching their own children at home while responsible for the learning of a group of other students. Health workers faced the onslaught of more people needing medical care and the psychological component of being exposed to a deadly disease on a daily basis. They faced the lack of schooling, childcare, and adult day services for their own dependents, while facing an increased demand on their work time.

Even in non-pandemic times caregivers face the challenge of providing self-care while caring for others. While the pandemic exacerbated this dual challenge, it is one that is always present for this group of parents and other caregivers.

In Focus: Working with My Family

Laci Lourenzo

In many cases working with family can be tricky and lead to big problems; in my family that is not the case. In fact we grew closer by working on the farm together. There was a lot of laughter and crying, good times and bad but, we were always together. The farm is the main reason that my family is so close and connected.

Figure 13.23. Family farming, while decreasing, can still be a bonding experience in the United States—a way of uniting work and family.

My family learned a lot about each other and ourselves on the farm. My parents realized that my siblings and I had different paths we needed to take in life, and they supported us even if it wasn’t including the farm. I am so grateful for the farm and the life I was given because of all those good days and bad.

Licenses and Attributions for Care Work

Open Content, Original

“In Focus: Pandemic Parenting” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Gendered Work Expectations, Taxes, and Family Wealth” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Caregivers at Home, Caregivers at Work” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Working with My Family” by Laci Lourenzo. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Care Work,” “Lack of Childcare and Eldercare,” and “Emotional Labor and Kin-Keeping” adapted from “Work inside the Home,” “Emotional Labor and Kin-Keeping,” and “Lack of Childcare” by Jane Forbes in “The Sociology of Gender” [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations: editing for brevity; emphasis on care work.

Figure 13.19. Photograph by Gerd Altmann. License: Pixabay License.

Figure 13.20. “Women, Work, and Parenting” from “Parents Juggle Work and Child Care During Pandemic” by the U.S. Census Bureau. Public domain.

Figure 13.21. Photograph by 963797. License: Pixabay License.

Figure 13.22. “Abraham & Johvanna – Ring” by FJH Photography. License: CC BY 2.0.

Figure 13.23. Photograph by Luemen Rutkowski on Unsplash. License: Unsplash License.

References

Alstott, A. L. (2013). Updating the welfare state: Marriage, the income tax, and social security in the age of individualism. Tax Law Review, 66, 720–722. https://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/fss_papers/4867/

Avi-Yonah, S. (2021, June 25) Women Took on Three Times as Much Child Care as Men During the Pandemic. Fortune. https://fortune.com/2021/06/25/women-men-unpaid-child-care-pandemic-gender-equality-workforce/

Boss, P. & Greenberg J. (1984) Family Boundary Ambiguity: A New Variable in Family Stress Theory. Family Process, 23(4), 535–546. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.1984.00535.x.

Blair-Loy, M., Hochschild, A., Pugh, A. J., Williams, J. C., & Hartmann, H. (2015). Stability and transformation in gender, work, and family: Insights from the second shift for the next quarter century. Community, Work & Family, 18(4), 435-454. doi:10.1080/13668803.2015.1080664.

Economic Policy Institute. (2020). Child Care Costs in the United States. https://www.epi.org/child-care-costs-in-the-united-states/#/OR

Gerstel, N., & Gallagher, S. K. (1993). Kinkeeping and distress: Gender, recipients of care, and work-family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 598-608. doi:10.2307/353341.

Hochschild, A. (1990, March). The Second Shift: Employed Women Are Putting in Another Day of Work at Home. Utne Reader, 38, 66–73.

Jenkins, D. A. (2013). Boundary ambiguity in gay stepfamilies: Perspectives of gay biological fathers and their same-sex partners. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54(4), 329-348. doi:10.1080/10502556.2013.780501.

National Center on Caregiving at Family Caregiver Alliance. (2015, February). Women and Caregiving: Facts and Figures. https://www.caregiver.org/resource/women-and-caregiving-facts-and-figures/

Schaeffer, K. (2022). Working Moms in the U.S. Have Faced Challenges on Multiple Fronts During the Pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/05/06/working-moms-in-the-u-s-have-faced-challenges-on-multiple-fronts-during-the-pandemic/

Sevilla, A., & Smith, S. (2020). Baby steps: The gender division of childcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(Supplement 1), S169-S186.

Sharma, N., Chakrabarti, S., & Grover, S. (2016). Gender differences in caregiving among family-caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World journal of psychiatry, 6(1), 7–17. doi:10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7.

Stephens, M. L. (2019). African American Grandmothers as Caregivers: Formal and Informal Learning and the Benefits to the Children in their Care. Journal of Negro Education, 88(4), 429-442. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/802573.