14.6 Generational Trauma and Resilience

Our sense of purpose and meaning can become amplified as a result of loss. For example, many of us have experienced the death of a loved one. After they are gone, we can gain a more immediate, broader understanding of what that person means to us. Often, we also receive sharper insights regarding the purpose of that relationship. We can also see meaning and purpose expand with loss if we examine family groups and their communities.

This section introduces meaning and purpose at the intersection of loss and equity. In Chapter 2, we discussed how understanding the diversity of family experiences includes developing awareness of the disproportionate ways they experience social problems. In addition, it includes paying attention to themes of social justice. Those themes include the unequal access families have to opportunity, care, and rights, or the current and historical persecution experienced by groups.

For example, we discussed humans’ ability to create meaning while in life-threatening circumstances, as was acknowledged by existential psychology. Victor Frankl observed that prisoners who survived Auschwitz found ways of transcending their day-to-day survival. They were able to find meaning and purpose in life through maintaining a future goal, acknowledging their capacity to change themselves, and finding an ultimate purpose in loving others. Enslaved Black people fostered spirituality, creativity, and purpose to survive a system that among other horrors was designed to crush their spirit to create a compliant workforce. Through religion, gathering in churches, and a myriad of creative arts, they were able to create meaning and purpose as a part of their lives.

The stories below explore the similar human capacity to amplify a sense of meaning and purpose amidst severe loss. We’ll look specifically at experiences expressed by two Indigenous people in the United States. The first is the experience of Ku Stevens, a member of the Yerington Paiute Tribe of Nevada. The second is the experience of Marie Wilcox, a member of the Wukchumni tribe, native to California.

Indigenous peoples around the world have experienced devastation in the form of discrimination, racism, and oppression, displacement from their lands, dissolution of their communities, and efforts to erase their cultures. These are all components of genocide, the deliberate destruction, in whole or in part, by a government or its agents of a racial, sexual, religious, tribal, or political minority. It can involve not only mass murder, but also starvation; forced deportation; and political, economic, and biological subjugation (Jones, 2006).

The wounding from these experiences exists across generations and is acknowledged in a number of ways. Dr. Maria Yellowhorse Braveheart writes about historical trauma and defines it as the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding across generations, including the lifespan, which emanates from massive group trauma” (Yellow Horse Brave Heart, 1995). Historical trauma is the result of tragic collective experiences of a community or generation. Examples are genocide; forced relocation; loss of spiritual practices, language, and culture; land dispossession; economic hardship; and war.

Related to historical trauma, generational trauma (also called transgenerational or multigenerational trauma) is also trauma that moves from one generation to the next. This refers to the way that trauma is passed on within families. Research shows that traumatic experiences of parents affect the biological, social, mental, or emotional development of their children; sometimes also their grandchildren through the ways they raise and relate to their children. Research is also pointing to ways that generational trauma is related to how certain genes are expressed in future generations (DeAngelis, 2019).

In each of their stories, Ku Stevens and Marie Wilcox share purpose and meaning that have emerged for them as a response to genocidal loss. They are also stories of survival and resilience among the backdrop of historical and generational trauma.

Some information detailed here may stir up or trigger unpleasant feelings or thoughts. The Indian Residential School Survivors Society encourages you to take time to care for your mental and emotional well-being. Please contact the Indian Residential School Survivors Society toll-free at 1-800-721-0066 or their 24-hour crisis line at 1-866-925-4419 if you require further emotional support or assistance.

Or:

The following content contains subject matter that may be disturbing to some visitors, especially to survivors of the residential school system. Please call xxxx if you or someone you know is triggered while reading the content of this website.

Remembrance Run

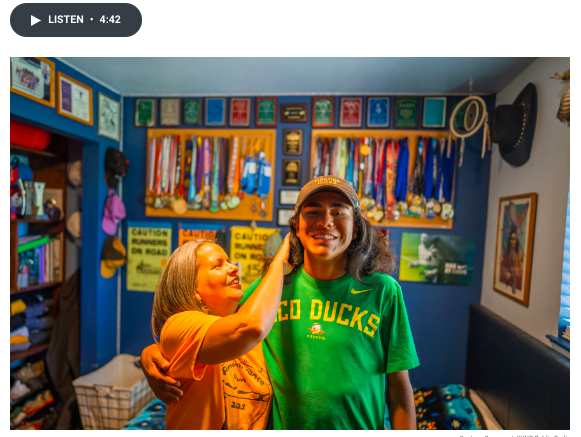

Figure 14.12. Kutoven (Ku) Stevens carries a staff during a run with Peace and Dignity Journey, an Indigenous and First Nation spiritual movement committed to the preservation of Native American culture.

Ku (short for Kutoven) Stevens (Figure 14.12) is a cross-country runner and a member of the Yerington Paiute Tribe of Nevada. Northern Paiute people call themselves Numu, which means human being in their language (Yerington Paiute Tribe, 2023). Ku has won two Nevada Gatorade state athlete of the year awards. In 2021 he became state champion and the fastest high school cross-country runner in all of Nevada. In 2022 he accepted an offer to join the track and cross-country teams at the University of Oregon (Streeter, 2021).

Ku’s inspiration for running comes from the story and struggle of his paternal great-grandfather, Frank Quinn. In the early 1900s, when Quinn was seven or eight years old, he was forced to leave his parents’ home and attend Stewart Indian School, an American Indian boarding school. Also called residential schools, more than 400 government-funded, and often church-run boarding schools like Stewart existed across the United States in the 19th and 20th centuries. They were designed to strip Native Americans of their cultural heritage and indoctrinate them with the cultural values of White Americans (Streeter, 2021; Newland, 2022). The boarding school system also coincided with the removal of many tribes from their ancestral lands.

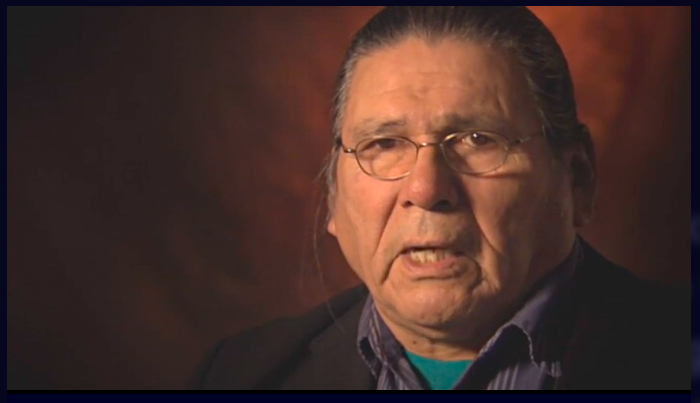

Watch this pair of videos that tell the experiences of Native Americans who were sent to residential schools in the United States. The first is “Taken from Their Families” (Figure 14.13) and the second is “The U.S. Government’s Education of Native American Children” (Figure 14.14).

Figure 14.13. Taken from Their Families [PBS Video] and Figure 14.14. The U.S. Government’s Education of Native American Children [PBS Video]

Native American survivors of U.S. government-run boarding tell their stories of what it was like for them to be taken from their families, brought into the schools, prevented from expressing their culture. The boarding school system was designed to de-indigenize Native American children. It had a lasting impact of damaging families.

Often Indigenous children arrived at the schools after being directly abducted by government agents. Congress had also authorized the Secretary of the Interior to withhold food rations from Indigenous families who did not release their children to the schools. Children were sent hundreds of miles away, and beaten, starved, placed in solitary confinement, or otherwise abused when they spoke their native languages or resisted rules and treatment in the schools.

Stewart Indian School was open between 1890 and 1980 and it operated as other boarding schools did. Like many other abducted students, Ku’s great-grandfather, Frank Quinn, decided to escape Stewart Indian School and run home. After two failed attempts he finally managed to navigate 50 miles of desert, returning to his reservation and family.

Inspired by his great-grandfather’s story, in 2021 Ku and a group of about 50 others ran for two days from Stewart to the reservation following the path Frank took as an 8-year-old when he escaped from the school. Watch this trailer for the film Remaining Native (Figure 14.15) for more of Ku’s story. As you do, what details can you identify about Ku’s inspiration for his run?

Figure 14.15. Remaining Native [Vimeo Video]. This preview of the film, Remaining Native, tells the story of a Ku Stevens who, through his running, honors the legacy of his great-grandfather and thousands of others who attended, escaped, and never made it home from Indian Boarding schools.

The Indian boarding schools present an example of one of the most prevalent causes of historical and transgenerational trauma: forced assimilation. Forced assimilation is the process by which a religious or ethnic minority group is forced to give up their own identity by taking on the cultural characteristics of an established and generally larger community.

In the video, Ku shares that: “Native Americans were sent to boarding schools to die.…If you didn’t die physically, you would come out of the school broken.” The process of forced assimilation through the boarding school system was in essence a spiritual and emotional breaking of young people and a breaking of intact communities. As Ku expresses, devastatingly, the boarding school system also meant a physical death for many young Native Americans. A cemetery sits nearby the Stewart School. Its graves are said to hold the remains of students who died there (Stewart Indian School, n.d.; Streeter, 2021).

In Canada, bodies, unmarked graves, and potential burial sites have been identified near residential school sites since the 1970s. In 2021 authorities began a renewed and more dedicated search and discovery of graves in their First Nations boarding schools. We now know that between 3,200 and 6,000 students died while attending the Canadian Indian residential school system (Tasker, 2015; Smith, 2015; Moran, 2020).

Soon after, the U.S. Department of the Interior began a study of U.S. burial sites near American Indian boarding schools. A 2022 report by the U.S. Department of the Interior expanded the original count of U.S. residential schools to more than 400, with at least 50 burial sites and at least 500 deaths of children among them (Newland, 2022).

The unearthing of this painful history furthered Ku’s inspiration to commemorate those who suffered from the boarding school system (Sagrero, 2022).

Ku also hosts a 50-mile “Remembrance Run” to honor his great-grandfather and all Native American children who survived American Indian boarding schools and to remember those who never came home. Listen to this podcast (Figure 14.16) where Ku shares his motivation and experience with the Remembrance Run.

Figure 14.16. Yerington Teen and Family Organized Run to Remember Survivors, Victims of Indian Boarding Schools [Podcast]. In this podcast, Ku Stevens talks about his inspiration to organize a 50-mile run honoring the survivors and victims of the Stewart Indian School.

What do you hear from Ku about the purpose and meaning he holds with his running?

Because I’m Native, I’m a descendant of my great-grandpa. It means a lot for my dad just to see what it was like, to understand what it was like to be that scared and to be that alone, to not have the typical resources that somebody would have on a trip like that.

I’m able to represent my people, and one of the best ways I know how, which is through running. So to be able to combine two things that I’m very passionate about, which is running and activism for my people, I’m able to really make a difference and an impact in a way that I could see, in a way that other people can understand, and in a way that I feel like is reaching a lot of people’s hearts, which is ultimately what the goal is.

Keeping Language Alive

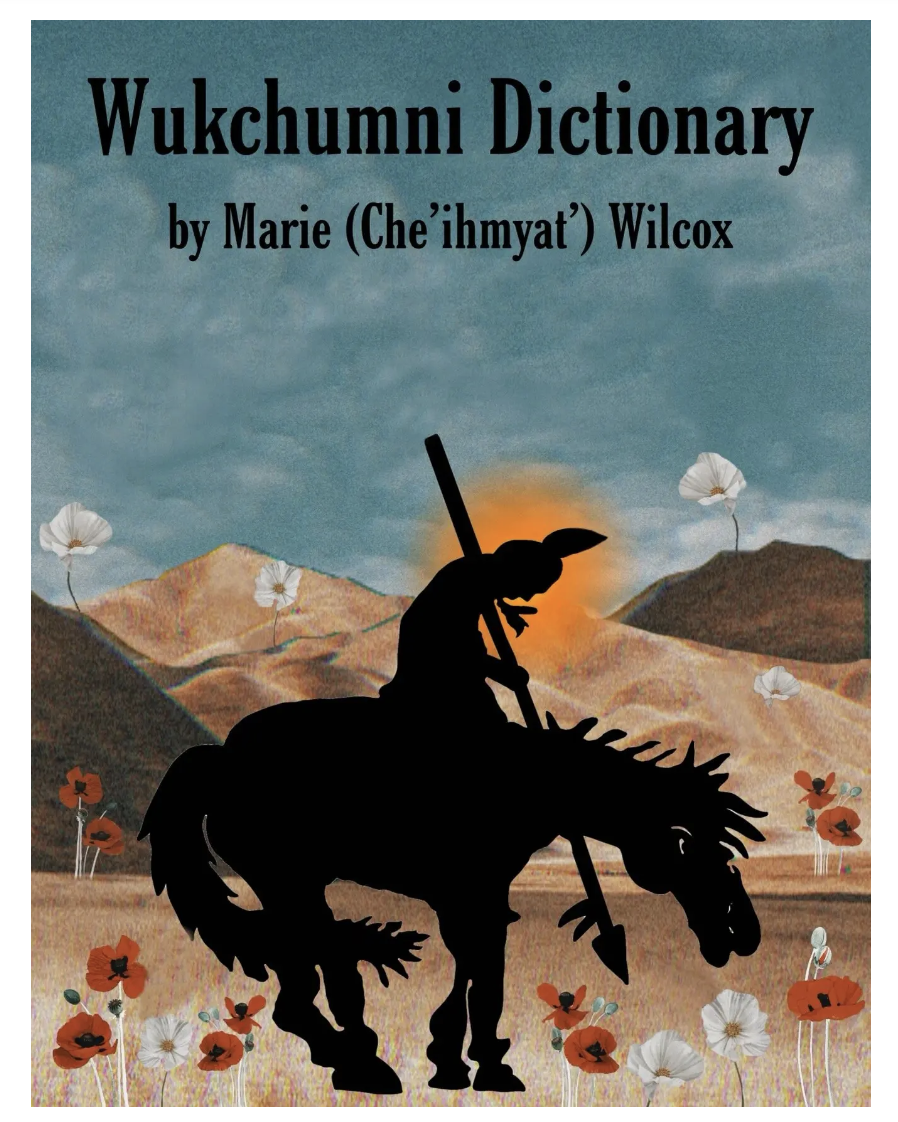

Figure 14.17. The dictionary of Wukchumni language created by Marie (Che’ihmyat’) Wilcox (Seelye, 2021).

Marie (Che’ihmyat’) Wilcox was a member of the Wukchumni tribe, a small community that is part of the larger Yokut Tribe native to Central California. Before European contact, the Yokut people reached 50,000 members, but today less than 200 identify as Yokut (Brown, n.d.; Mineral King Preservation Society, n.d.).

Marie resided on the Tule River Reservation, and before she died in 2021, she was the last fluent speaker of the Wukchumni language. A couple decades before her death, she commenced work on a Wukchumni dictionary to support the revitalization of her tribe’s language (Figure 14.17). This work was also a tribute to her grandmother who took care of her and spoke the language. The New York Times shared part of her story (Seelye, 2021):

(Ms. Wilcox) started writing down words in Wukchumni as she remembered them in the late 1990s, scrawling on the backs of envelopes and slips of paper. Then she started typing them into an old boxy computer. Soon she was getting up early to devote her day to gathering words and working into the night.

Ms. Wilcox also recorded the words in her dictionary to capture their pronunciation, and traveled to conferences throughout California to meet with other tribes who struggle with language loss (Seelye, 2021).

As we mentioned earlier, one of the strategies for forcibly assimilating Indigenous children at the boarding schools was to forbid them from speaking their own languages. The 2022 Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report documents that federal American Indian boarding schools were “designed to separate a child from his reservation and family, strip him of his tribal lore and mores, force the complete abandonment of his native language, and prepare him for never again returning to his people” (Newland, 2022, p. 51). The report quotes a communication to the Secretary of the Interior in 1886 that tells more of their strategies for assimilation (Newland, 2022, p. 54):

No Indian is spoken[:] …There is not an Indian pupil whose tuition and maintenance is paid for by the United States Government who is permitted to study any other language than our own vernacular—the language of the greatest, most powerful, and enterprising nationalities beneath the sun.

For Native American families, even as the boarding schools began to close, they still feared that teaching their children their languages would cause suffering for them (Lutz, 2007). Indigenous languages in the United States have been in decline for decades. Sixty-five are extinct and 75 are near extinction, with only a few elder speakers left (Sparks, n.d.).

Watch the video about Marie, called “Marie’s Dictionary,” in Figure 14.18. As you watch, consider: What expressions of purpose and meaning do you notice? What purpose and meaning does Marie experience from creating the dictionary?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iRDmRXCizEM

Figure 14.18. Marie’s Dictionary [YouTube Video]. This video tells the story of Marie Wilcox, the last fluent speaker of the Wukchumni language and the dictionary she created in an effort to keep her language alive.

Language, Identity, and Family

Language is important to families and their communities because they are the vehicle for cultural expression and heritage. In addition, languages often convey knowledge about life and the natural world known by communities that can only be expressed in their own language.

Inspiration for language revitalization spans generations in Indian Country. Ricky Nelson, also known as N8V ACE, is a Diné (Navajo) rap artist originally from Red Mesa, Arizona. He calls his music “cultural rap.” His song “Native Rap” features him rapping in Diné. In an interview he describes that his music “could be used as a tool to inspire the youth to use our Diné language.” Watch the video in Figure 14.19. In what ways do you hear N8V ACE expressing his identity? Why do you hear it is important to him?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OuOzNLB2Zzw

Figure 14.19. Native Rap [YouTube Video]. N8V ACE, a Diné (Navajo) musician performs his song “Native Rap” in his Diné language. His work is about “…encouraging people to be proud of who they are (especially the youth), to learn about culture / heritage, to keep tradition alive, and to preserve Native languages.” (Anon. n.d.)

The producers of “Marie’s Dictionary” explain some more (Global Oneness Project, 2020):

- Oral storytelling has been a part of the human experience for thousands of years, providing a way for language to be remembered without documentation…

- “The world stands to lose an important part of the sum of human knowledge whenever a language stops being used. Just as the human species is putting itself in danger through the destruction of species diversity, so might we be in danger from the destruction of the diversity of knowledge systems,” wrote Indigenous language revitalization advocate and linguist Leanne Hinton.

- …Cultural historian Larry Swalley from the Lakota tribe said, “The language, the whole culture of the Lakota, comes from the song of our heartbeat. It’s not something that can quickly be put into words. It’s a feeling, it’s a prayer, it’s a thought, it’s an emotion—all of these things are in the language.”

Licenses and Attributions for Generational Trauma and Resilience

Open Content, Original

“Generational Trauma and Resilience” by Aimee Samara Krouskop. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 14.12. Insert photograph of Ku

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.13. “Taken from Their Families” © PBS. License: XXX.

Figure 14.14. “The U.S. Government’s Education of Native American Children” © PBS. License: XXX.

Figure 14.15. Video trailer of the film Remaining Native” © SCHH Productions. Used with permission.

Figure 14.16. “Yerington Teen and Family Organized Run to Remember Survivors, Victims of Indian Boarding Schools” © KUNR Public Radio. License: Used with permission.

Figure 14.17. Cover of The Dictionary of Wukchumni Language by Marie (Che’ihmyat’) Wilcox, The New York Times. License: Fair Use.

Figure 14.18. “Marie’s Dictionary” © Global Oneness Project. License: Standard YouTube License.

Figure 14.19. “Native Rap” © N8V ACE. License: Standard YouTube License.

References

Anon. n.d. “BIO.” N8V ACE. Retrieved (https://n8vmovement.com/pages/about).

Best Start Resource Centre. 2010. A child becomes strong: Journeying through each stage of the life cycle [PDF]. Toronto, Ontario. pp. 1-54. https://resources.beststart.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/K12-A-1.pdf

Brown, Kimberly. “Preserving Her Tribe’s Language.” Cal@170. Retrieved May 10, 2023. https://cal170.library.ca.gov/preserving-her-tribes-language/.

Four directions teachings. 2015. Retrieved from http://www.fourdirectionsteachings.com/

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A, & Kerrie, K. 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Well-being. In P. Dudgeon., H. Milroy, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and well-being principles and practice (2nd Ed.) (pp. 55-68). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Global Oneness Project. 2020. “Cultural Heritage: Recording a Native Language Dictionary.” Inverness, CA: Global Oneness Project. Retrieved May 11, 2023 (https://www.globalonenessproject.org/lessons/cultural-heritage-recording-native-language-dictionary

Jones, Adam. 2006. “Chapter 1: The Origins of Genocide” (PDF). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Publishers. pp. 15–18. ISBN 978-0-415-35385-4. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

Lutz. 2007. “Saving America’s Endangered Languages.” Cultural Survival. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

Mineral King Preservation Society, “History of the Living History Community.” https://mineralking.org/history-of-a-living-community/.

Moran, Ry. 2020. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission.” October 5. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Newland, Bryan. Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report. U.S. Department of the Interior, May 2022. Retrieved May 10, 2023. https://www.bia.gov/sites/default/files/dup/inline-files/bsi_investigative_report_may_2022_508.pdf.

Seelye, Katharine Q. “Marie Wilcox, Who Saved Her Native Language From Extinction, Dies at 87.” New York Times, 6 Oct. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/10/06/us/marie-wilcox-dead.html.

Smith, Joanna. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s report details deaths of 3,201 children in residential schools.” Toronto Star. December 15. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

Sparks, Lillian. n.d. “Preserving Native Languages: No Time to Waste” U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Native Americans, Office of the Administration for Children and Families. Retrieved May 10, 2023, at https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ana/preserving-native-languages-article

Streeter, Kurt. “To Honor His Indigenous Ancestors, He Became a Champion.” The New York Times, 17 Nov. 2021. NYTimes.com, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/17/sports/ku-stevens-running-nevada.html.

Tasker, John Paul. 2015. “Residential schools findings point to ‘cultural genocide’, commission chair says.” CBC News. May 29. Retrieved May 10, 2023.

Stewart Indian School. (n.d.). Welcome to the Stewart Indian School Website. https://stewartindianschool.com/. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

Gee, G., Dudgeon, P., Schultz, C., Hart, A, & Kerrie, K. 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social and Emotional Well-being. In P. Dudgeon., H. Milroy, & R. Walker (Eds.), Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and well-being principles and practice (2nd Ed.) (pp. 55-68). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Yellow Horse Brave Heart-Jordon, M. (1995). The return to the sacred path. Social Work, Northampton, Smith College School for Social Work: 182.

“Yerington Paiute Tribe.” Yerington Paiute, https://www.yeringtonpaiute.us. Accessed 25 Apr. 2023.

Sagrero, G. (2022). “Yerington Teen and Family Organized Run to Remember Survivors, Victims of Indian Boarding Schools. 2022)” KUNR Public Radio, 17 Aug. 2022, https://www.kunr.org/local-stories/2022-08-17/ku-stevens-family-remembrance-run-survivors-victims-indian-boarding-schools.