4.4 Changing Demographics

Population trends that demonstrate changes in lifespan, fertility, and family formation within the United States are connected to the ways that families form and function in their nurturing relationships. These demographic changes are captured via large studies and surveys; most of the data are collected, analyzed, and publicized by the U.S. federal government (or collected separately by states and then combined). These big trends help us to understand how families change over time.

Declining Birth, Fertility, and Fecundity Rates

In addition to the interpersonal aspects of caregiving and parenting, it is important to look at the changes that are occurring as the population ages to birth, fertility, and fecundity rates. Many of these changes are similar in other developed countries, but we will focus on the United States.

It may be helpful to understand the three different rates that are declining. The birth rate is the number of live births per 1,000 women in the total population. The fertility rate looks more closely at age and tells us proportionally how many women in a specific age group gave birth compared to the total number of women in that age group. Both of these rates are declining in the United States. In addition, the fecundity rate, which is the rate of women who are able to give birth and wish to do so, is declining as well.

In general, the population is aging in the United States: People are living longer and fewer children are being born. The birth rate is declining across all education, income, and age levels, with just one exception. While older women (ages 45 to 49) are having more children, this is a very small number in comparison to all the other groups that are having fewer children (Hamilton et al., 2021).

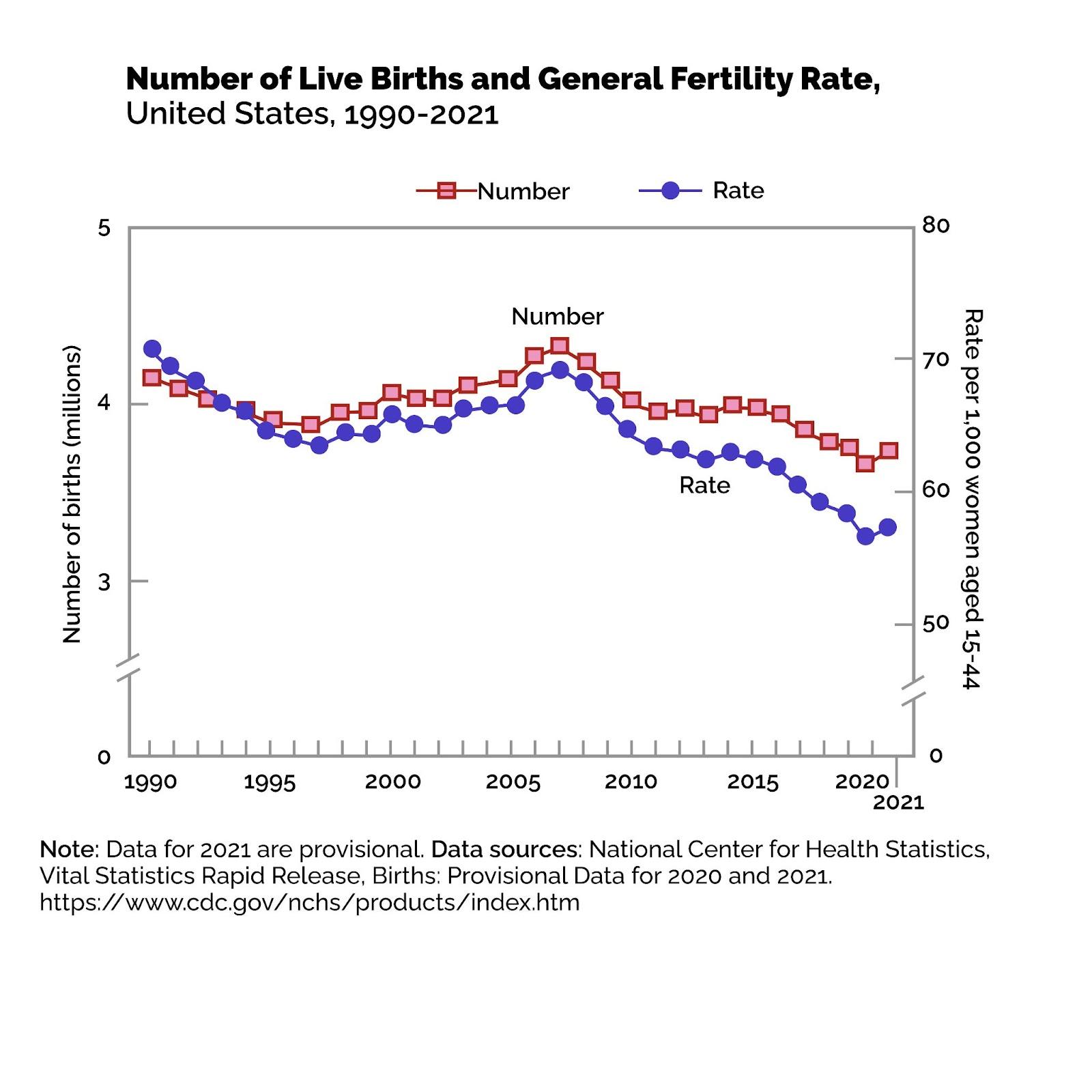

The graph in Figure 4.10 demonstrates the number of live births in the United States between 1990 and 2020 (30 years.) The red line represents the number of actual births in the millions (e.g., there were over 4 million births in 1990 and about 3.6 million births in 2020). The blue line represents the fertility rate per 1,000 women (e.g., there were just over 70 births per 1,000 women in 1990 and 55.8 births per 1,000 women in 2020).

Figure 4.10. Any way that you measure it, there are fewer babies being born in the United States. Image description.

Because these rates are declining across all social identities in the United States, it is difficult for researchers to isolate what is contributing to this decline, although economics, medical factors, and climate change are all believed to be factors.

While the fertility rate has been on the decline in the United States since 1960, the health and economic crises related to the COVID-19 pandemic appear to have negatively affected the desire to have children in the United States (Barroso, 2021). Not only has the birth rate dropped lower, but adults are increasingly saying that they don’t expect to have children or don’t expect to have more children. Again, there does not seem to be one deciding factor that influences the decision, with the majority of childless adults saying that “they just don’t want to have children” (Brown, 2021).

Single Parenting, Co-Parenting, and Stepparenting

Children are growing up in a variety of parenting arrangements that include having one “single” parent, being parented by co-parents who live in different homes, and having additional parents who are not biologically or legally related to them (stepparents). And there are variations on these variations! For example, a stepparent may live in the same home, actively parent the child, and not be legally married to the child’s parent. Or a stepparent may legally adopt the child, effectively becoming another full parent. To put it simply, our language and terminology has not caught up with the complexity of family structures that involve children.

In six states, however, laws have been passed that recognize that children may have more than two parental attachment figures. These laws expressly allow courts to recognize more than two parents. With parentage come both rights and responsibilities. These laws give children who have multiple adults in their lives access to all of those adults when disputes or tragedies arise.

For example, a child who might have otherwise been assigned to the foster care system when a parent dies could have access to another recognized parental figure, such as a stepparent, aunt, surrogate mother, or egg or sperm donor who has been active in the child’s life. In one West Virginia case, this doctrine assigned parental care to both the aunt and uncle who had parented the child, as well as to his legal mother, who rehabilitated herself over a period of 10 years (Josin & NeJaime, 2022). This trend points in the direction of the legal system catching up with the multiple ways that children may be cared for.

Pew Research conducted a randomized, nationally representative study of 1,807 parents in the United States in 2014. While not every family form is captured, this study provides us with an overview of the changing structures of families with children.

The number of children who are living with parents in a first marriage has decreased from 73% in 1960 to 46% in 2014. That means 26% more of 2014’s children have diverse living arrangements. Dramatically more children are living with single parents; 9% lived with single parents in 1960 and 26% lived with single parents in 2014. Seven percent of children lived with cohabiting parents in 2014; this number was zero or unrecorded in 1960 (Pew Research Center, 2015).

Multigenerational Families and Changing Life Expectancy

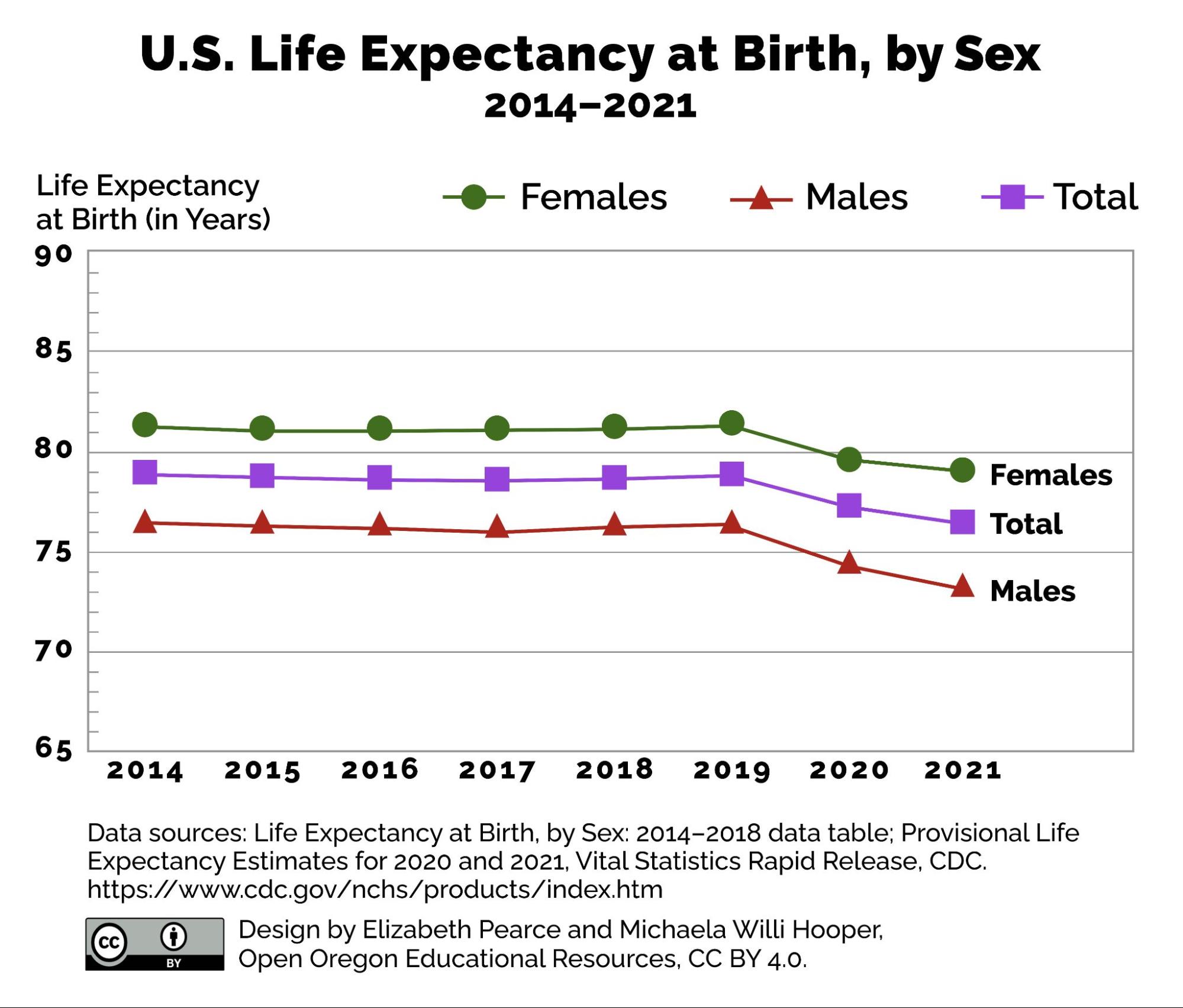

To fully understand the increase in multigenerational families (where more than two generations live together) and grandfamilies (where grandparents or great-grandparents provide the primary care for their grandchildren), it is important to note a significant trend in the United States. For centuries, the mortality rate, or the rate of death for a particular group in a particular area, had decreased. While rates vary by gender, race, and ethnicity, overall life expectancy rates increased in the United States between 1860 and 2015.

Since 2015, however, life expectancy has dropped for all genders, races, and ethnicities in the United States, with the most dramatic changes occurring in 2021. These most recent changes have been attributed to negative social trends such as diet, sedentary lifestyles, increased medical costs, increased rates of drug use and suicide, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In spite of this recent change, when you look at change over the past century, people in the United States, in general, are living longer as shown in Figure 4.11. This is true for both men and women (Hamilton et al., 2021). They are also living healthier and more active lives. This, combined with the decrease in fertility, means that older adults have fewer children and grandchildren who are more widely spaced apart by age. This creates a capacity for both more active grandparenting than in previous generations, as well as the possibility of actual parenting of grandchildren and other caregiving relationships. It is believed that the combination of families having fewer children and living longer has led to more involvement by grandparents with their grandchildren. Simply put, people are living long enough to see their grandchildren be born and to be an active part of their lives.

Figure 4.11. While women have had longer life expectancy than men for a long time, both groups faced a significant decline between 2019 and 2021 in the United States. Image description.

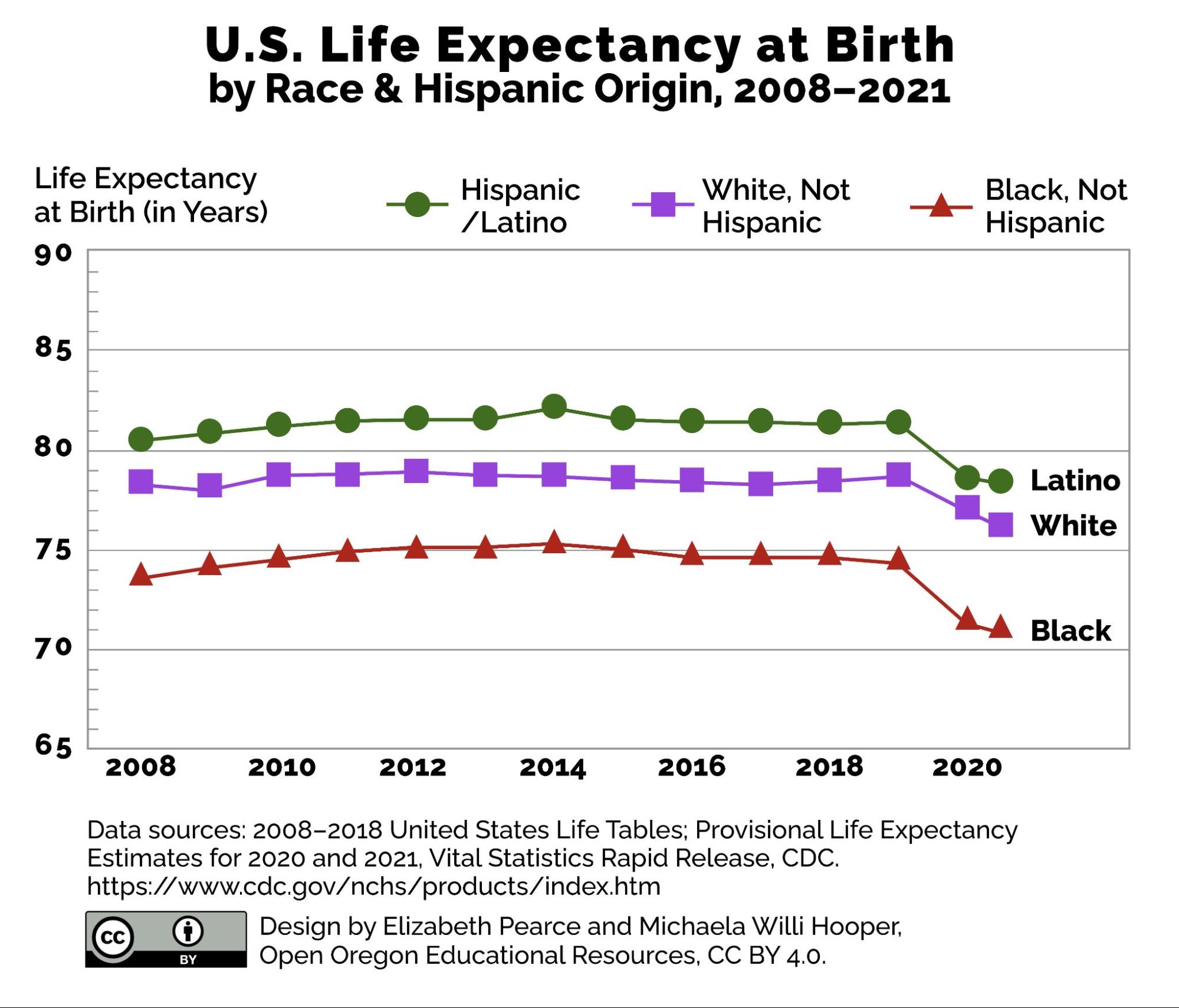

Life expectancy is also correlated with race and ethnicity, as shown in Figure 4.12. When we consider family life, we can think about both quality of life and length of life. Both of these figures illustrate important trends in life expectancy. It is important to note that life expectancy in the United States trails other comparable wealthy developed countries.

Figure 4.12. While people of all races and ethnicities have seen declines in life expectancy, Latino and Black populations have seen a more dramatic decline between 2018 and 2020. Image description.

While life expectancy is declining, parents may increasingly need help from older relatives. Rates of single parents and divorced parents have increased. These parents may call on their own parents for financial support, childcare, shared housing, or other needs. In addition, social problems such as addiction and mass incarceration also contribute to the need for more adults to be involved in parenting. Caregiving and closeness is exchanged across multiple generations, as shown in Figure 4.13.

Older adults, including grandparents, are more frequently involved in caregiving and supporting children and grandchildren than ever before. It is important to note that it is not only middle-class or wealthy grandparents that are taking an active role in family caregiving; poor and working-class grandparents are also stepping in to help out their children and grandchildren.

Figure 4.13. Multigenerational families usually include three generations: children, parents, and grandparents. Grandfamilies usually include grandchildren and grandparents, with the skipped generation of parents playing a range of roles from no involvement to a lot of involvement, but not living in the same household.

Multigenerational households are on the rise after reaching a low of 12% in 1980. In 2016 roughly 20% of adults lived in a multigenerational household, with an increase being attributed to the economic recession that started in 2009 (Cohn & Passel, n.d.). The National Association of Realtors reports that multigenerational home purchases increased during the pandemic by four percentage points (Ventiera, 2020). These trends point out the connection between economic change and living arrangements that affect family relationships and structure.

Licenses and Attributions for Changing Demographics

Open Content, Original

“Changing Demographics” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.10. “Number of Live Births and General Fertility Rate, United States, 1990–2021” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi-Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.11. “U.S. Life Expectancy at Birth, by Sex, 2014–2021” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0. Data from 2008–2018 United States Life Tables; Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2020 and 2021, Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Figure 4.12. “U.S. Life Expectancy at Birth by Race & Hispanic Origin, 2008–2021” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0. Data from 2008–2018 United States Life Tables; Provisional Life Expectancy Estimates for 2020 and 2021, Vital Statistics Rapid Release, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.13. Boy (13–15) with parents and grandparents by moodboard on flickr.com. License: CC BY 2.0.

References

Barroso, A. (2021, May 7). With a potential ‘baby bust’ on the horizon, key facts about fertility in the U.S. before the pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/05/07/with-a-potential-baby-bust-on-the-horizon-key-facts-about-fertility-in-the-u-s-before-the-pand

Brown, A. (2021, November 19). Growing share of childless adults in U.S. don’t expect to ever have children. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/11/19/growing-share-of-childless-adults-in-u-s-dont-expect-to-ever-have-children/

Cohn, D., & Passel, J. S. (n.d.). A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Pew Research Center. Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational-households/

Hamilton, B. E., Martin, J. A., & Osterman, M. J. K. (2021, May). Births: Provisional Data for 2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr012-508.pdf

Josin, C. G. & NeJaime, D. (2022, January 28). The next normal: States will recognize multiparent families. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/01/28/next-normal-family-law/

Pew Research Center (2015, December 17). Parenting in America: Outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial situation. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/12/17/parenting-in-america/

Ventiera, S. (2020, December 24). All in the family: How the pandemic accelerated the rise in multigenerational living. Real Estate News & Insights | Realtor.Com®. https://www.realtor.com/news/trends/all-in-the-family-how-pandemic-spurred-rise-in-multigenerational-living/