4.6 Family Forms and Functions

This text began with a chapter about ideas that are socially constructed, including the picture of the traditional or ideal family. That nuclear family model, often represented as two White, married, heterosexual, middle-class parents with 2.2 children, is only one form of families involving caregiving and sometimes children. Figure 4.16 illustrates another family form. In this section, we will distinguish between family form and family functionality.

Figure 4.16. Family structure, or form, such as one parent and one child, is separate from the health of the family, or the family function.

Families come in many forms, including those described previously. Family forms include parents who are married, living together, divorced, stepparents, adoptive parents, single parents, grandparents in parenting roles, and foster parents. Forms may include blended and step families, half siblings, and stepsiblings. The form of any household may include more than two generations or people who are not related legally or by blood. All of these are differing forms, or structures, of family life, such as the one pictured in 4.17. The family form is merely the physical makeup of the family members in relationship to one another. These differing forms are sometimes called the “complexities” of family life in academic literature. The form does not indicate how healthy the family is or how well the family members behave toward one another, known as the family function.

Families function in a range of ways and differently over time. How well does any given family function? That answer is complicated to measure in one moment and also over time. It includes the functionality of each individual family member, the functionality of any two members’ relationship, and the overall functionality of the entire family. What indicates healthy functionality? Here are a couple of indicators; you may also have your own standards of what indicates healthy functioning:

- Respect for the individuality of each family member

- Communication that is direct but not purposefully harmful or painful

- Commitment to each other

- Parent(s) who prioritize their children’s needs

Figure 4.17. Family forms have developed and changed over time, and there is no one typical family structure.

It is important to understand and to separate form and functionality. Because many of our social institutions identify one kind of family as “the norm,” it is easy to assume that somehow other kinds of families are “less than.” That is not the case. As discussed throughout this text, family forms have developed and changed over time. It is critical to note that there are many well-functioning families that include single parents; gay parents; parents who are poor, have been incarcerated, or have lots of children; or people who have no children. All families face challenges, and families that look “perfect” on the outside may have dysfunction, behaviors that cause harm to the self, family members, or society. As you navigate the world, do your best to keep this in mind, because the societal message is often the opposite.Throughout this chapter we discuss families who may not fit that idealized family form but who are just as likely to have loving, functional family relationships.

Families without Children

An increasing number of partnered adults are completing their families without having children. As discussed earlier, all three rates (birth, fertility, and fecundity) are declining in the United States. This section will discuss the societal stigma that can be associated with not having children.

Childless or Childfree?

For many decades in the United States, there was a predictive life course for heterosexual, White, middle-class families. This was considered the ideal, a part of the “American Dream.” Steps included going to school, starting a career, getting married, and then “starting a family,” which really meant having children. Couples were expected to produce babies soon after marriage.

But this norm, never attainable for all families, has become increasingly diversified. Now it is known that a family can be a “family” without including children. There is greater awareness of the difficulties that a heterosexual couple may have with conceiving a child. There is greater acceptance of same-sex couples who may have difficulty adopting or using medical and biological means to procreate. And there is increased understanding of couples who do not wish to have children and consider their families complete without them. These families express their desire to remain childfree by choice.

Increased awareness and acceptance does not equate with a disappearance of social stigma, however. Harmful viewpoints that equate pregnancy with “becoming a woman” or that describe men as more masculine if they get someone pregnant quickly continue to resonate in our society, along with the idea that one’s life is not “complete” until they have children.

Same-Sex Parenting

LGBTQ+ parenting refers to the care and guidance of children by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer parents, as well as other members of this broad community. People within this community can become parents through various means, including but not limited to adoption, foster care, insemination and other medical pregnancy methods, and surrogacy.

LGBTQ+ parents have been proven to be as effective as heterosexual parents (although this comparison in and of itself reflects the binary heteronormative standard, itself a social construction). The primary research in this area has been conducted on same-sex parents. This research was originally driven by the desire for data when parents divorced and one parent identified as gay. Both heterosexual and LGBTQ+ parents sought rationales that would justify the child custody arrangement that they preferred.

In Focus: Science Twins

Leslie Hammond

Our journey to parenthood was long and complicated and full of science! When you’re trying to conceive as a same-sex couple, you learn just how miraculous the conception of life really is.

Figure 4.18. This picture of embryos shows the earliest photo of our son (we’re pretty sure he’s the one on the right). Five years later, an embryo from this same batch, which had been frozen since their conception in 2009, grew into our son’s little brother. We call our children “science twins” and tell them all about the science that brought them onto this earth. We’re so grateful that our dream of having a family became a reality.

An argument against LGBTQ+ parenting has been made that children will face bullying and harassment in either the public arena or in court cases involving child custody. It is true that these families face marginalization and discrimination. But is this a reason to deny these families their rights, essentially marginalizing them further? These authors argue that like other families from marginalized groups, it is the work of social institutions and society to diminish and eliminate the causes of discrimination.

Foster and Adoptive Families

One way to protect children from abuse or neglect is to remove them from their primary caregivers and place them into foster care or with family members. Foster care is regulated by the states, but it generally consists of a system in which a minor is placed into a private home of a state-certified caregiver referred to as a “foster parent,” with a family member, or occasionally in a group setting approved by the state. The placement of the child is arranged through the government or a social service agency. The state, via its child services department, maintains responsibility for the child.

In the United States, the number of children in foster care steadily grew between 2010 and 2019 from about 405,000 to roughly 424,000, when it began to level off and drop to 391,098 in 2021. As of February 2023, 113,589 children in foster care are waiting to be adopted (AFCARS Report #29, 2023). This means that these children’s parents have lost their legal rights and custody, leaving them without any permanent legal caregivers (the government assumes this responsibility until someone adopts the children). The average age of youth waiting to be adopted from foster care is eight years old.

Families with Disabled Members

Disabled people have always faced problems created because society is structured without disability in mind. For instance, the rail transport system assumes that all passengers can step over a gap between a train and the platform, that they can walk to their seat, and indeed that sitting in a “standardized” seat is an option. There are countless practices that exclude or marginalize disabled people. The way things routinely get done in everyday life can be problematic for disabled people, from the material infrastructure of a building to the ways people interact. For instance, people with dementia might rely on familiar, clear signage to find their way in and out of a building, but they also need people who will give them time to communicate and wait for a response in a respectful way.

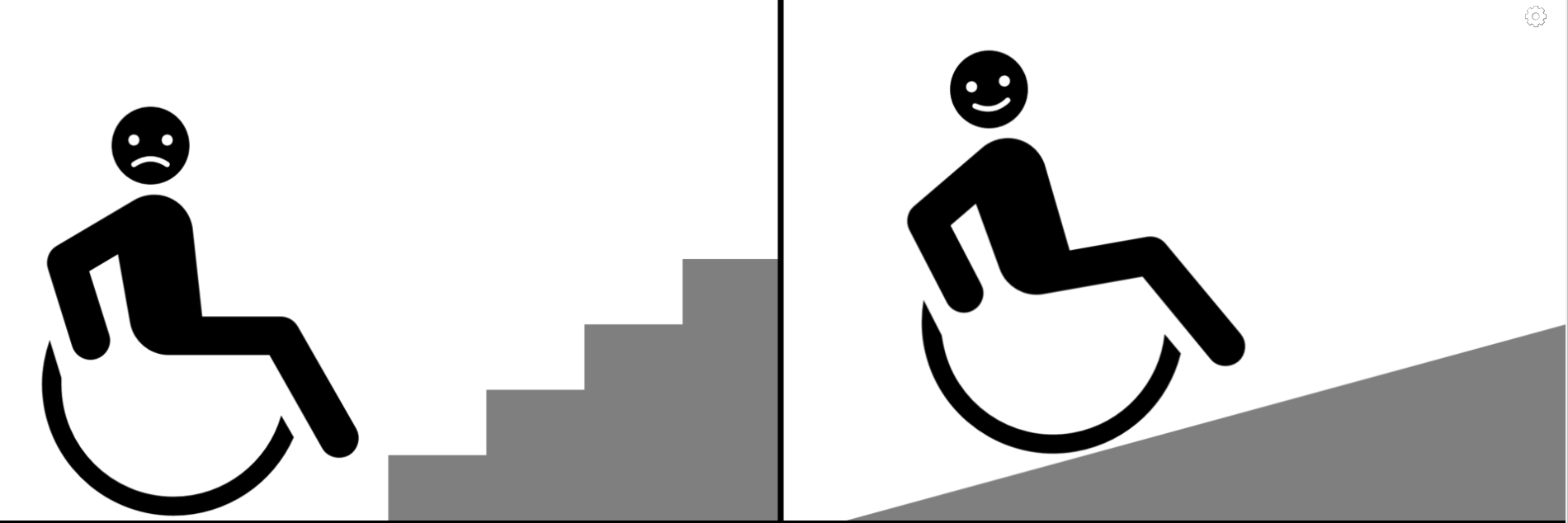

How can we start to understand the ways that social structures interact with families who have members with disabilities? It is important to understand the dichotomy between the social and medical model of disability. The medical model, which has dominated thinking in the United States, sees the individual with a difference in ability as having a personal problem. The social model focuses on the society and culture disabled individuals live in, making adjustments that allow all people to access activities and services. Here is an example of an adaptation in Figure 4.18.

Figure 4.19. The first image focuses on the individual having a problem. The second image shows how an adapted environment can contribute to equity in access.

The social model directs our attention toward the external barriers facing disabled people, and now we need to find better ways of analyzing and understanding those barriers. It also emphasizes that people who have a disability can be active participants in deciding what kinds of societal supports and policies will be effective.

A disabled family member affects all other members of the family as well as the overall family dynamic. Parents and caregivers must respond to the disabled child who faces more systemic challenges to participating in daily life. While there are services and funding available for families with disabled members, there is not a centralized system, forcing families to spend valuable time and financial resources to apply for these assets. Many parents believe that the available resources are not sufficient—if parents need to focus on one child accessing basic activities such as school, health care, or transportation, they may have less time or financial resources for their other children or partners.

Caring for adults, such as siblings, close friends, or parents, also affects family dynamics. When those adults are able to find support that removes society’s barriers, it can positively affect the rest of the family. One more common reason for adult caregiving within a family is dementia and related diseases. As people are living longer, the number of adults who face Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia is increasing.

Here are some words from the Forget-Me-Not Club, a dementia support group in the United Kingdom:

Everyone will tell you the same thing. You’re diagnosed, and then it’s “You’ve got dementia. Go home and we’ll see you next month.” What we need is for someone, like a counselor or someone else with dementia, to tell us at that point, “Life isn’t over.” You can go on for ten or fifteen years. And you’re not told, you’re just left. And I thought, tomorrow my day had come. The fear and the anxiety sets in, and then the depression sets in, doesn’t it? I think when you’re diagnosed, you should be given a book. And on the front of the book, in big letters, it should say: “Don’t panic” (Forget-Me-Not Club, n.d.).

These are people who do not want to be seen through a medical lens as individual tragedies; they are turning a dementia diagnosis into a situation where they are in control and can support each other and make their voices heard. However, social practice theory also reminds us about the importance of material resources. For instance, in order to meet each other and have a collective sense of peer support, people need to have spaces that are not institutionalized that they feel they can “own.” All too often, we have seen very well-intentioned group activities taking place in old, large halls, or where people are routinely sitting in configurations that make communication difficult. But we have also seen the Forget-Me-Not Club, in an ordinary, homely environment, where staff members interact on a basis of equality with the members who have dementia.

This is just one of many examples where we are finding that people can do things differently and where society can move toward inclusion and empowerment.

In Focus: Dreaming of Juniper

Hailey Adkisson

When you have children, you have certain dreams for them. There are big ones, like going to college, getting married, having their own children. There are smaller ones, like taking their first steps, learning to ride a bike, or shopping for a prom dress. But what happens when those dreams can’t become a reality? How do we celebrate our children for who they are while still allowing ourselves the ability to mourn our dreams?

Figure 4.20. Juniper in a sun hat, playful and silly.

When Juniper was six months old, we noticed she was exhibiting some strange movements; her arms would jerk up, her body would crunch, and her head would dip. At first, it would happen every few days in a cluster of 5 to 10. Later, these movements began happening at every sleep/wake cycle and lasted for 20 to 40 at a time.

Maybe it was reflux? Maybe it was just a weird baby movement? We contacted her pediatrician and were told if she was breathing regularly, it wasn’t an emergency. Something told me this wasn’t quite right, and we drove to the nearest emergency room for another opinion. The doctors there saw Juniper having the movements, but like her pediatrician, they told us not to worry.

I tried to reassure myself of this as we drove an hour to the nearest children’s hospital the next day, but I knew in my gut that something was seriously wrong. Juniper was hooked up to an electroencephalogram (EEG) to test for abnormalities in her brain waves. When the attending physician came into the room, the look on his face told me it wasn’t good news.

Juniper was diagnosed with a rare and catastrophic form of pediatric epilepsy called Infantile Spasms (IS). Each movement we were seeing was actually a tiny seizure, and she was having hundreds a day. In addition to seizures, her background brain activity presented in a pattern called hypsarrhythmia. Think of this as static on a radio. It’s hard to comprehend the story because the static keeps interrupting the message. Additionally, each seizure was as if her brain was “rebooting” like a computer—shutting down, then starting back up. If we didn’t stop the hypsarrhythmia and the spasms, Juniper would not be able to develop because she wouldn’t be able to encode anything she was experiencing or learning. Her brain would be too cluttered.

The outcome of IS on children largely depends on how they respond to treatment and what the underlying cause of the seizures is. Epilepsy is a symptom of something else: genetic variations, metabolic syndromes, a traumatic brain injury, or brain malformations. A child could respond quickly to treatment, but they could have a genetic variation that causes intellectual and physical disabilities in the future.

First, stop the spasms. Then, figure out the cause.

Juniper was prescribed an extremely high-dose steroid treatment that we injected into her chubby baby thighs twice a day. My beautiful and happy baby gained five pounds in a month and was miserable. Unfortunately, it didn’t stop the spasms. Another medication with horrible side effects, another relapse. At this point, we decided to get a second opinion, and it was discovered that the cause of Juniper’s seizures was a malformation called focal cortical dysplasia.

Juniper celebrated her first birthday hooked up to an EEG. Four days later, she underwent a hemispherectomy. This aggressive surgery involved removing half her brain in the hope that removing the dysplasia while she was young would allow her brain to rewire itself. While we may be able to achieve seizure freedom, it didn’t come without a cost. Juniper lost vision on the left side of both her eyes. She had paralysis in her left arm and left leg and will never have fine motor skills in her left hand. She will likely have trouble with numbers, memory, self-control, and emotional regulation. Her chance of autism increased. She may be nonverbal.

Figure 4.21. Hailey and Juniper snuggle in a hospital bed.

As a parent, you make decisions on behalf of your child every day in hopes of providing them with the best quality of life. While our decision was one I wish no other parent ever had to make, our goal was still the same: We needed to give Juniper a chance at the best quality of life, and that meant surgery.

But what is a “good” quality of life? For Juniper, it can’t be based on our norms—a house, a good job, financial security, a marriage, 2.5 kids and a Labrador.

So is it mobility? Independent feeding? Verbal communication? What if that isn’t her reality? Does that mean she has a bad life? How do I know if my daughter has a good life? To know, I have to ask myself:

Is she happy?

Is she comfortable?

Is she safe?

Constant seizures would not allow her to be any of these things.

While I don’t know what Juniper will be able to do in the future, there are some obvious limitations. When my son asked if Juniper would be able to have babies, I cried. These are not Juniper’s dreams; they are mine. My children are an extension of my own dreams. While I hope she never feels a loss of anything and thinks her life is beautiful and amazing, I will feel that loss. Like any loss, it will take time to grieve.

It’s hard to explain what it is like to have a child with a disability. You love them fiercely and are amazed by them every day, but you also mourn what could have been. You get to celebrate every tiny thing, moments I missed with my son because they happened so quickly. At the same time you wish life wasn’t so challenging for them and that things like “pushing to sit” came naturally.

The uncertainty about Juniper can be incapacitating at times because there is so much we don’t know. What I do know is that she has changed me.

I am stronger than I thought I was. I am more resilient. I learned how to advocate for my child, look a doctor in the eyes, and demand a plan. I learned the importance of trusting my gut when it comes to parenting. I often think back to what would have happened if I had brushed off my intuition in those early days of her diagnosis. Juniper looked and acted like a “normal” baby. Even after her spasms became more intense and I documented an episode on video, her pediatrician at the time and an entire team of ER doctors told us not to worry—it was no big deal. The truth is, IS is an emergency. It is an extremely rare and catastrophic form of epilepsy that often goes misdiagnosed for months (even by medical professionals). If left untreated, IS can have devastating impacts on development.

Most importantly, I have learned to appreciate tiny moments of joy that I never slowed down to see before. While I still experience deep grief about the trauma my daughter and my family have gone through, I try to stay focused on the present as much as possible. Yes, my dreams for my daughter have had to shift. Instead of mourning what she won’t be able to do, I try to focus on who she is now.

Figure 4.22. Juniper has wonderful happy times with her family, as well as big challenges.

Juniper has a smile that seems too big for her face and a belly laugh that fills an entire room with joy. She loves being outside, especially when she is in her swing. She will grab at any necklace, watch, or shiny thing within reach. There isn’t a food she dislikes. She’s addicted to her pacifier. Her brother is her favorite person.

Juniper is more than her disability. She is more than her seizures. She is more than her brain surgery. Her journey hasn’t fit with the dreams I had for my children, but dreams change. They have to. Otherwise, you’ll miss out on the beautiful reality that’s right in front of you.

Figure 4.23. Hailey and Juniper smile at each other.

Hailey Adkisson, MA, is a full-time community college professor; a wife; a mother of three; and in her “free time,” an unofficial therapist, nurse, and pharmacist to her daughter, Juniper, who has med-resistant epilepsy. Since her daughter’s diagnosis, Hailey has immersed herself in the disability community, connecting with families across the country who have young children with medical complexities. She believes building community is key to providing support for parent caregivers like herself. You can reach out to Hailey at @growing_juniper on Instagram.

Poverty

Throughout this textbook, you will read about how families who experience poverty are impacted in terms of their daily needs: housing, food, water, education, and more. Each chapter will delve into one of these specific needs and highlight how socioeconomic status combined with other social characteristics such as sex, gender, race, and ethnicity contribute to intersectionality and the likelihood of discrimination.

But how does poverty affect the public function of caregiving in families?

As highlighted earlier in this chapter, socioeconomic status, more than race or ethnicity, has been identified as a key correlator of the strategies and practices that parents use to raise their children. Why this is so is a difficult question to answer. It can be deduced that parents with a higher socioeconomic status have more resources and therefore more choices about where they live and what activities their children are involved in.

Does this make their parenting or their love for their children superior? Of course not. But it does tell us that they may be able to afford options for their families that others cannot. The effects of poverty affect family dynamics in at least two ways. First, because in reality “time is money,” parents who are poor often have less time as well as less money—so they have less time to spend with their children. Second, because they are at the lower end of the class structure, they are more likely to be discriminated against based on socioeconomic status than other families. Both of these factors may lead to others seeing them as less devoted to parenting, but it is actually poverty that is getting in the way, not a lack of love or care for their children.

Families in lower socioeconomic groups face more judgment and discrimination. Parents in these groups may have to make more difficult choices with both time and money, such as, “Should I make a home-cooked meal, or should I sit on the floor and play with my child—which means I have to serve a frozen meal?” Even that choice may create more choices, as a prepared frozen meal will likely cost more than something that takes time to assemble. “Should I pay for this needed car repair or for a new pair of shoes for my child?” presents related dilemmas. Enter the societal culture that judges parents on what can be seen: worn-out shoes or new shoes?

In this text, we will continually look for systemic solutions to social problems such as the number of families in the United States who experience poverty. Enlightening research tells us that it is possible to impact families positively via social programs. A recent study led by Columbia University in New York demonstrates the effect of cash gifts to poor families:

This study demonstrates the causal impact of a poverty reduction intervention on early childhood brain activity. Data from the Baby’s First Years study, a randomized control trial, show that a predictable, monthly unconditional cash transfer given to low-income families may have a causal impact on infant brain activity. In the context of greater economic resources, children’s experiences changed, and their brain activity adapted to those experiences…

Early childhood poverty is a risk factor for lower school achievement, reduced earnings, and poorer health, and has been associated with differences in brain structure and function. Whether poverty causes differences in neurodevelopment, or is merely associated with factors that cause such differences, remains unclear. Here, we report estimates of the causal impact of a poverty reduction intervention on brain activity in the first year of life…

In sum, using a rigorous randomized design, we provide evidence that giving monthly unconditional cash transfers to mothers experiencing poverty in the first year of their children’s lives may change infant brain activity. Such changes reflect neuroplasticity and environmental adaptation and display a pattern that has been associated with the development of subsequent cognitive skills (Troller-Renfree et al., 2022).

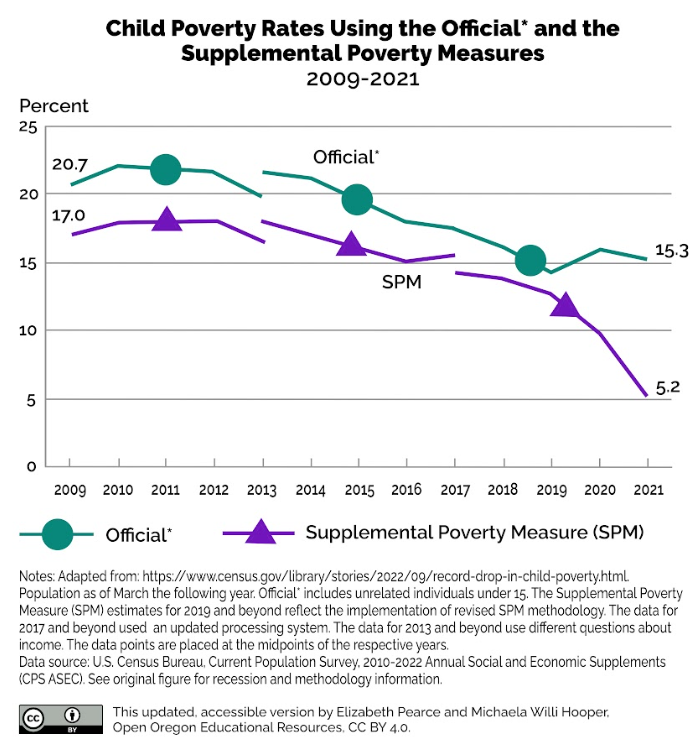

This study lends hope that the cycle of poverty can be interrupted. Policies and programs that contribute to equity can make a positive difference in the outcomes for families experiencing poverty. Unfortunately, child poverty continues to be high in this country.

Figure 4.24 This graph shows that when cash benefits are given to families on a monthly basis (rather than a lump sum) child poverty can be dramatically reduced (purple line). Image Description

A recent federal policy demonstrates a practical application of cash benefits. In the American Rescue Plan of 2021, the Child Tax Credit was not only expanded but also distributed differently. Prior to 2021, parents received the child tax credit in a lump sum after submitting their taxes. Many expenses related to having children, such as childcare, rent/mortgage, transportation, and extracurricular activities are payable monthly or weekly—not in one lump sum. But in 2021, families received a monthly distribution of about $250 to $300 a month (The White House, n.d.). Not only was this monthly income predictable, it was also expanded to the poorest families, those who do not pay income taxes, who were previously excluded from this benefit. This resulted in a dramatic decrease in child poverty, as shown in Figure 4.24. Unfortunately, the extension of this program has now been eliminated.

COVID-19 Pandemic

It is difficult to imagine a more life-altering period of time than the span of the COVID-19 pandemic from late 2019 to the present day. If we look back at the ecological systems theory, this pandemic qualifies as a chronosystem: a large sociohistorical event that ripples inward through the concentric circles of families’ lives. It has affected the cultural practices of our macrosystem (like wearing masks and social distancing); it has changed exosystem elements such as restaurants, stores, and places of worship; and it has dramatically altered our microsystem settings such as workplaces, schools, and perhaps even our homes. And what of the mesosystem, the connections and relationships between all of these systems? Well, by inference, those have been changed as well.

Large catastrophic events are known to be linked with mental health burdens. Caregivers are not exempt from these mental health changes; in fact, they may be greater than for those who are not caring for others. While the long-term effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are unknown, it is likely that individual and family outcomes will be changed. Already it is known that K–12 and college students are experiencing much higher levels of depression (Active Minds, 2020). With people of all ages experiencing mental health challenges, it is likely that this will affect their parent-child relationships and other caregiving connections.

Licenses and Attributions for Family Forms and Functions

Open Content, Original

“Socially Constructed Ideas: Form and Function” and all subsections except those noted below by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“Same-Sex Parenting” by Shyanti Franco and Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

“In Focus: Science Twins” by Leslie Hammond. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.18. “Science Twins” by Leslie Hammond. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

“In Focus: Dreaming of Juniper” by Hailey Adkisson. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.19. “Juni in Sun Hat” by Hailey Adkisson. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.20. “Hospital Snuggles” by Hailey Adkisson. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.21. “Juni at home” and “Juni on the Move” by Hailey Adkisson. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.22. “Mother-Daughter” by Hailey Adkisson. License: CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 4.24 “Child Poverty Rates Using the Official and Supplemental Poverty Measures” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources. License: CC BY 4.0. Based on data from U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, 2010-2022 Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC). See original figure for recession and methodology information.

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/record-drop-in-child-povertyhtml

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Families with Disabled Members” includes an excerpt from Disability Needs to be Central in Creating a More Just and Equal Society in Comment and Analysis from the School for Policy Studies by Val Williams that has been edited and combined with original paragraphs focused on the United States by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Figure 4.16. “A Genderfluid person and a Transgender Woman Practicing Tarot” by Zackary Drucker and The Gender Spectrum Collection. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.17. “Father, Walking, Nature” by Laubenstein Ronald. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 4.18. “A Wheelchair User’s Problems Being Caused by an Inaccessible Environment” by MissLunaRose12. License: CC BY-SA 4.0.

References

Active Minds (2020, April). The Impact of COVID-19 on Student Mental Health. https://www.activeminds.org/studentsurvey/

AFCARS Report #29—February 2023 | Vol. 24, No. 1. (n.d.). Retrieved February 20, 2024, from https://cbexpress.acf.hhs.gov/article/2023/february/afcars-report-29/a47818711b7bd91080f4631ee54bcb8f

Forget-Me-Not Club (n.d.) Dementia support. https://www.forgetmenotclub.co.uk/help.html

The White House (n.d.). The child tax credit. ttps://www.whitehouse.gov/child-tax-credit/

Troller-Renfree, S. V., Costanzo, M. A., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Gennetian, L. A., Yoshikawa, H., … & Noble, K. G. (2022). The impact of a poverty reduction intervention on infant brain activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(5), e2115649119.