6.4 Working Outside of the System: Social Movements and Activism

We’ve spent a large portion of this chapter focused on historical and current aspects of the way social processes work in this country: the census, voting, representation, the courts, and elected officials. We have attempted to uncover some of the flaws, gaps, and structures that lead to unequal representation and treatment of families. Change within these processes is possible, but sometimes challenging because the existing structures favor some groups and reinforce negative bias and inequality toward others. Working outside of the systems to push for change is an alternative for people whom the systems have marginalized.

Social Movements

A social movement may be defined as an organized effort by a large number of people to bring about or impede social, political, economic, or cultural change. Defined in this way, social movements might sound similar to special-interest groups, and they do have some things in common. But a major difference between social movements and special-interest groups lies in the nature of their actions. Special-interest groups normally work within the system via conventional political activities such as lobbying and election campaigning. In contrast, social movements often work outside the system by engaging in various kinds of protest, including demonstrations, picket lines, sit-ins, and sometimes outright violence (Figure 6.15).

Figure 6.15. Social movements are organized efforts by large numbers of people to bring about or impede social change. Often they try to do so by engaging in various kinds of protest, such as the march depicted here.

In this section we will look at selected periods of time and social movements—ones that have influenced family roles and relationships while simultaneously advocating for equal rights and responsibilities. In addition, we will emphasize the intersectional nature of social movements and social change. Let’s start with feminism.

Feminism and Family Roles

Feminist movements have generated and nurtured feminist theories and academic knowledge. Feminist movements use critical reflection about the world to change it. It is because of various social movements—feminist activism, workers’ activism, and civil rights activism throughout the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries—that “feminist history” is a viable field of study today. Feminist history is part of a larger history that draws on the experiences of traditionally ignored and disempowered groups (e.g., factory workers, immigrants, people of color, lesbians) to rethink and challenge the histories that have been traditionally written from the experiences and points of view of the powerful (e.g., colonizers, representatives of the state, the wealthy)—the histories we typically learn in high school textbooks.

What has come to be called the first wave of the feminist movement began in the mid-19th century focused on laws that would give women the right to vote, the right to education and employment, and striking down laws in which her property passed to her new husband upon marriage. The Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments (Falls, n.d.), passed in 1848, describes many “repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman” and includes 16 submitted facts, including these:

- He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

- He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

- He has made her, morally, an irresponsible being, as she can commit many crimes, with impunity, provided they be done in the presence of her husband. In the covenant of marriage, she is compelled to promise obedience to her husband.

- He has so framed the laws of divorce, as to what shall be the proper causes of divorce; in case of separation, to whom the guardianship of the children shall be given, as to be wholly regardless of the happiness of women—the law, in all cases, going upon the false supposition of the supremacy of man, and giving all power into his hands.

- He has monopolized nearly all the profitable employments, and from those she is permitted to follow, she receives but a scanty remuneration.

- He closes against her all the avenues to wealth and distinction, which he considers most honorable to himself. As a teacher of theology, medicine, or law, she is not known.

- He has denied her the facilities for obtaining a thorough education—all colleges being closed against her.

Figure 6.16. White, middle-class, first-wave feminists fought for the right to vote, own property, and access education and employment.

Demanding women’s enfranchisement, the abolition of men’s control over their wives, and access to employment and education were quite radical demands at the time. These demands, pictured in Figure 6.16, confronted the ideology of the cult of true womanhood, summarized in four key tenets—piety, purity, submission, and domesticity—which held that White women were rightfully and naturally located in the private sphere of the household. Think back to our discussion of the idealized nuclear family in Chapter 2.

This emphasis on confronting the ideology of the cult of true womanhood was shaped by the White middle-class standpoint of the leaders of the movement. The cult of true womanhood was an ideology of White womanhood that systematically denied Black and working-class women access to the category of “women,” because working-class and Black women, by necessity, had to labor outside of the home.

The Intersectionality of Social Movements

Meanwhile, working-class women and women of color knew that mere access to voting did not overturn class and race inequalities. As feminist activist and scholar Angela Davis writes, working-class women “were seldom moved by the suffragists’ promise that the vote would permit them to become equal to their men—their exploited, suffering men” (Davis, 1981). Furthermore, the largest suffrage organization, the National American Woman Suffrage Association—a descendent of the National Women Suffrage Association—barred the participation of Black women suffragists in its organization.

The abolitionist movement—which sought to end slavery—and the racial justice movement followed the end of the Civil War. In some ways, both movements were largely about having self-ownership and control over one’s body (Cott, 2000). For enslaved people, that meant the freedom from lifelong, unpaid, forced labor, as well as freedom from the sexual assault that many enslaved Black women suffered from their enslavers. For married White women, it meant recognition as people in the face of the law and the ability to refuse their husbands’ sexual advances. This analogy between marriage and slavery had resonance at the time, but it problematically conflated the unique experience of the racialized oppression of slavery that African American women faced with a very different type of oppression than White women. While White women abolitionists and feminists of the time made important contributions to anti-slavery campaigns, they often failed to understand the uniqueness and severity of enslaved women’s lives and the complex system of chattel slavery (Davis, 1983).

Despite their marginalization, Black women emerged as passionate and powerful leaders. Ida B. Wells, a particularly influential activist who participated in the movement for women’s suffrage, was a founding member of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) (Figure 6.17). As a journalist, she authored numerous pamphlets and articles exposing the violent lynching of thousands of African Americans. She said that lynching in the Reconstruction Period was a systematic attempt to maintain racial inequality, despite the passage of the 14th Amendment in 1868 (which held that African Americans were citizens and could not be discriminated against based on their race) (Wells, 1893). Additionally, thousands of African American women were members of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, which was pro-suffrage, but did not receive recognition from the predominantly middle-class, White National American Woman Suffrage Association.

Figure 6.17. Ida B. Wells was a founding member of the NAACP and a journalist who exposed the lynchings of thousands of African Americans.

As you can see, feminist and abolitionist movements were working toward equal rights, but often people at the intersection of both movements, Black women, were sometimes left out.

World War II and Family Well-Being

Social movements are not static entities; they change according to movement gains or losses, and these gains or losses are dependent on the political and social contexts of the time. Following women’s suffrage in 1920, feminist activists channeled their energy into institutionalized legal and political channels for effecting changes in labor laws and attacking discrimination against women in the workplace. While workplaces were now more available to women than they were just a few decades earlier, inequities in pay and working conditions were quite visible. World War II provides an excellent example of how women, people of color, and working families all gained rights and wealth.

While millions of women were already working in the United States at the beginning of World War II, labor shortages during World War II allowed millions of women to move into higher-paying factory jobs that had previously been occupied by men. The Lanham act allocated monies for both universal childcare and additional services for school-age children including an extended supervision period. Schools also provided additional services such as child infirmaries, multiple meals during the school day, and take-home meals for 50 cents per family (State of Oregon, n.d.). These examples of wrap-around childcare, sick childcare, and nutritious meals all show the ways that the government was able to support working families in a meaningful way.

Simultaneously, nearly 125,000 African American men fought in segregated units in World War II, often being sent on the front guard of the most dangerous missions (Zinn, 2003). For example, the G.I. Bill that provided post-secondary educational benefits to returning veterans did not substantially increase educational attainment for Black men, especially those in the South. The number of colleges who admitted Black people were limited and both African Americans and women still faced discrimination when trying to access their benefits (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2002). While the life course theory points to this world war as a process that significantly affected and changed life outcomes in a positive way for men and families, this was certainly more the case for White veterans. Japanese Americans whose families were interned also fought in the segregated units that had the war’s highest casualty rates (Odo, 2017; Takaki, 2001).

Civil Rights and Second-Wave Feminism

Following the end of the war, both the women who had worked in high-paying jobs in factories and the African American men who had fought in the war returned to a society that was still deeply segregated, and they were expected to return to their previous subordinate positions. Despite the conservative political climate of the 1950s, civil rights organizers began to challenge both the segregation of Jim Crow laws and the segregation experienced by African Americans on a daily basis. The landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling of 1954, which made “separate but equal” educational facilities illegal, provided an essential legal basis for activism against the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow laws. Eventually, the Black Freedom Movement, also known now as the civil rights movement, would fundamentally change U.S. society and inspire the second-wave feminist movement and the political movements of the New Left (e.g., gay liberationism, Black nationalism, socialist and anarchist activism, the environmentalist movement) in the late 1960s.

In many ways, the second-wave feminist movement was influenced and facilitated by the activist tools provided by the civil rights movement. Drawing on the stories of women who participated in the civil rights movement, they challenged gender norms that kept women in the private sphere of the home and childrearing, and not in politics or activism (Debois and Dumenil, 2005). Women who were involved in the civil rights movement became activists in the second-wave feminist movement, as well as employing tactics that the civil rights movement had used, including marches and nonviolent direct action. Additionally, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 not only prohibited employment discrimination based on race, but also sex discrimination.

Although the second-wave feminist movement challenged gendered inequalities and brought women’s issues to the forefront of national politics in the late 1960s and 1970s, the movement also reproduced race and sex inequalities. Black women writers and activists such as Alice Walker, bell hooks, and Patricia Hill Collins developed Black feminist critiques of the ways in which second-wave feminists often ignored racism and class oppression and how they uniquely impact women and men of color and working-class people (Figure 6.18).

Figure 6.18. Black feminist bell hooks argues that you can’t fight sexism without also fighting racism, classism, and homophobia.

Black feminist bell hooks (1984) argued that feminism cannot just be a fight to make women equal with men, because such a fight does not acknowledge that all men are not equal in a capitalist, racist, and homophobic society. Thus, hooks and other Black feminists argued that sexism cannot be separated from racism, classism, and homophobia, and that these systems of domination overlap and reinforce each other. Therefore, she argued, you cannot fight sexism without fighting racism, classism, and homophobia.

One of the first formal Black feminist organizations was the Combahee River Collective, formed in 1974. The Combahee River Collective Statement was one of the first explorations of multiple oppressions, including heterosexism as well as racism and sexism (Eisenstein, 1978). This is a short excerpt from the statement:

There is …[a] realization that comes from the seemingly personal experiences of individual Black women’s lives. Black feminists and many more Black women who do not define themselves as feminists have all experienced sexual oppression as a constant factor in our day-to-day existence. As children we realized that we were different from boys and that we were treated differently. For example, we were told in the same breath to be quiet both for the sake of being “ladylike” and to make us less objectionable in the eyes of white people. As we grew older we became aware of the threat of physical and sexual abuse by men. However, we had no way of conceptualizing what was so apparent to us, what we knew was really happening.

The continued focus on the complexity of identities and their intersections, provided a foundation for the next wave of social movements.

Third-Wave Feminism and Queer Movements

Third-wave feminism is, in many ways, a hybrid creature. It is influenced by second-wave feminism, Black feminisms, transnational feminisms, Global South feminisms, and queer feminism. This hybrid activism comes directly out of the experiences of feminists in the late 20th and early 21st centuries who have grown up in a world that supposedly does not need social movements. This is because “equal rights” for racial minorities, sexual minorities, and women have been guaranteed by law in most countries. The gap between law and reality—between the abstract proclamations of states and concrete lived experience—however, reveals the necessity of both old and new ways of working outside of the system.

In a country where women are paid only 81% of what men are paid for the same labor, where police violence in Black communities occurs at much higher rates than in other communities, where 58% of transgender people surveyed experienced mistreatment from police officers in the past year, where 40% of homeless youth organizations’ clientele are gay, lesbian, bisexual, or transgender, where people of color—on average—make less income and have considerably lower amounts of wealth than White people, and where the military is the most funded institution by the government, feminists have increasingly realized that a coalitional politics that organizes with other groups based on their shared (but differing) experiences of oppression, rather than their specific identity, is absolutely necessary (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019; James et al., 2016; Durso & Gates, 2012; Heywood & Drake, 1997; Duggan, 2002).

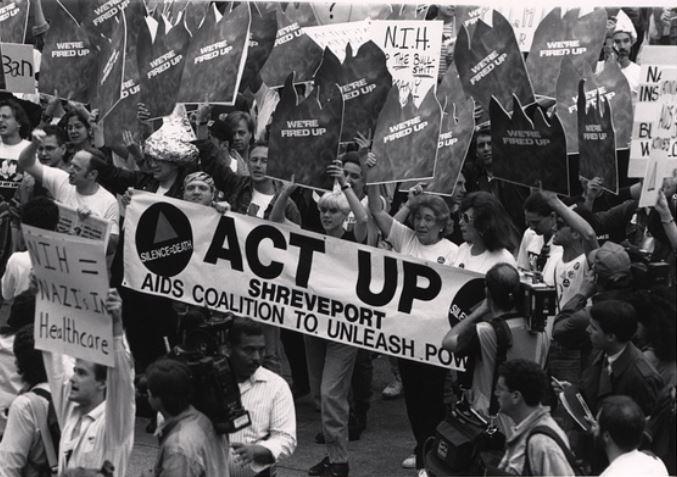

In the 1980s and 1990s, third-wave feminists took up activism in a number of forms, including a focus on health during the AIDS epidemic, a disease that has now killed tens of millions of people worldwide (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2023). Beginning in the mid-1980s, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) began organizing to press an unwilling U.S. government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS (Figure 6.19). In the latter part of the 1980s, a subset of individuals began to articulate a queer politics, explicitly reclaiming a derogatory term often used against gay men and lesbians, and distancing themselves from the gay and lesbian rights movement, which they felt mainly reflected the interests of White, middle-class gay men and lesbians. The queer turn sought to develop more inclusive sexually diverse cultures and communities, which aimed to welcome and support transgender and gender nonconforming people and people of color.

Figure 6.19. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) began organizing to press an unwilling U.S. government and medical establishment to develop affordable drugs for people with HIV/AIDS.

Around the same time as ACT UP was beginning to organize in the mid-1980s, sex-positive feminism came into currency among feminist activists and theorists. Sex-positive feminists argued that sexual liberation, within a sex-positive culture that values consent between partners, would liberate not only women, but also men. Sex-positive feminists argued that no sexual act has an inherent meaning, and that not all sex, or all representations of sex, were inherently degrading to women. In fact, sexual politics and sexual liberation are key sites of struggle for White women, women of color, gay men, lesbians, queers, and transgender people—groups of people who have historically been stigmatized for their sexual identities or sexual practices (Rubin, G. 1984). Therefore, a key aspect of queer and feminist subcultures is to create sex-positive spaces and communities that not only validate sexualities that are often stigmatized in the broader culture, but also place sexual consent at the center of sex-positive spaces and communities.

In a media-savvy generation, it is not surprising that cultural production is a main avenue of activism taken by contemporary activists. For example, the Riot Grrrl movement, based in the Pacific Northwest of the United States in the early 1990s, consisted of do-it-yourself bands predominantly composed of women, the creation of independent record labels, feminist zines, and art. Their lyrics often addressed gendered sexual violence, sexual liberationism, heteronormativity, gender normativity, police brutality, and war. Feminist news websites and magazines have also become important sources of feminist analysis on current events and issues. Magazines such as Bitch and Ms., as well as online blog collectives such as Feministing and the Feminist Wire function as alternative sources of feminist knowledge production. Creating alternative culture on people’s own terms can be considered a feminist act of resistance as well.

Third-wave feminism’s insistence on grappling with multiple points of view, as well as its persistent refusal to be pinned down as representing just one group of people or one perspective, may be its greatest strong point. Similar to how queer activists and theorists have insisted that “queer” is and should be open-ended and never set to mean one thing, third-wave feminism’s complexity, nuance, and adaptability become assets in a world marked by rapidly shifting political situations.

Black Lives Matter and Allies

In 2013, prompted by the killing of Trayvon Martin, Alicia Garza wrote a Facebook post, “Black people. I love you. I love us. Our lives matter.” Friend Patrisse Cullors added a hashtag to “Black Lives Matter.” And Opal Tometi suggested the three Black women create an online presence that became a “container” for the Black protests and work toward “a multiracial democracy that works for all of us” (TIME, 2020). Together they are credited with starting the Black Lives Matter movement.

Figure 6.20. Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi are interviewed by Mia Birdsong at TEDWomen Conference 2016 – It’s About Time.

The year 2020, near the beginning of a global pandemic and prompted by the murder of George Floyd, saw increased activism in Black Lives Matter both among Black people and allies. Nationally, White people have shown an increased understanding of the discrimination and bias that Black people continue to experience. This could be a time of enlightenment, understanding, and rapid change. The authors encourage readers to continue to examine how past and current policies affect the experiences of Black and multiracial families.

One aspect of the current Black Lives Matter movement is the increased involvement of people from other races and ethnicities as allies, people who form relationships and advocate with or for others who are marginalized. These can be White people who do not experience racism but work to support and advocate for equity. Often, an ally will come to this position through interactions with a close friend or family member who experiences racism. But others may not have close experience with people of color. “Listening” to stories, whether through music, the news, novels, or podcasts, is critical to understanding someone else’s lived experience. In this podcast, you can hear about one ally, a young Korean American, who surprised himself by speaking up.

https://www.npr.org/2020/07/20/892974604/one-korean-americans-reckoning

Allyship is critical to changing systems of bias, dissemination, and the corresponding privilege that other groups experience. The focus of the story should continue to be on Black individuals who have experienced ongoing systemic harm to their families. They have continued to advocate for understanding of their experience, representation, belonging, and an equal opportunity to participate safely in society and institutions.

Licenses and Attributions for Working Outside of the System: Social Movements and Activism

Open Content, Original

“Black Lives Matter and Allies” by Elizabeth B. Pearce. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Movements” is adapted from “Understanding Social Movements” in Sociology by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations: edited for brevity and clarity.

“Feminist and Family Roles,” “The Intersectionality of Social Movements, “World War II and Family Well-Being,” “Civil Rights and Second-Wave Feminism,” and “Third-Wave Feminism and Queer Movements” are excerpted from “Historical and Contemporary Feminist Social Movements” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken. License: CC BY 4.0. Excerpted sections of the chapter are included and framed with a focus on family well-being. Additions include the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments and relations to family roles; family services at the Kaiser Shipyards; the G.I. Bill, life course theory, and discriminatory effects; and the Combahee River Collective Statement.

Figure 6.15. “Clampdown, We Are the 99%” by Glenn Halog. License: CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 6.16. “Votes for Women Sellers, 1908” by LSE Library. Public domain.

Figure 6.17. “Ida B. Wells Barnett” by Mary Garrity. Public domain.

Figure 6.18. “bell hooks” by Cmongirl. Public domain.

Figure 6.19. “ACT UP Demonstration at NIH” by NIH History Office. Public domain.

Figure 6.20. “TEDWomen2016_20161027_MA016918_1920” by Marla Aufmuth/TED. License: CC BY-NC 2.0.

References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019, November). Highlights of women’s earnings in 2018. https://www.bls.gov/opub/reports/womens-earnings/2018/home.htm

Cott, N. (2000). Public vows: A History of marriage and the nation. Harvard University Press.

Davis, A. (1981). Working women, Black women, and the history of the suffrage movement, in A. Avakian and A. Deschamps (Eds.) A Transdisciplinary Introduction to Women’s Studies (pp. 73-78). Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Davis, A. (1983). Women, race, class. Random House.

Debois, E. & Dumenil, L. (2005). Through women’s eyes: An American history with documents. St. Martin Press.

Duggan, L. (2002). The new homonormativity: The sexual politics of neoliberalism. In R. Castronovo & D. Nelson (Eds.), Materializing democracy (pp. 175-194). Duke University Press.

Durso, L.E., & Gates, G.J. (2012). Serving Our youth: Findings from a national survey of service providers working with lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless. The Williams Institute with True Colors Fund and The Palette Fund. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/80×75033

Eisenstein, Z. (1978). The Combahee River Collective: The Combahee River Collective Statement

Falls, M. A. 136 F. S. S., & Us, N. 13148 P. 315 568-0024 C. (n.d.). Declaration of sentiments—Women’s rights national historical park (U. S. National park service). Retrieved December 14, 2023, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/declaration-of-sentiments.htm

Heywood, L. & Drake, J. (1997). Third wave agenda: Being feminist, doing feminism. University of Minnesota Press. hooks, b. (1984). Feminist theory: From margin to center (2nd ed.). South End Press.

James, S. E., Herman, J. L., Rankin, S., Keisling, M., Mottet, L., & Ana, M. (2016). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. https://www.transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/USTS-Full-Report-FINAL.PDF

Kaiser Family Foundation, (2023, July 26). The global hiv/aids epidemic. https://www.kff.org/global-health-policy/fact-sheet/the-global-hiv-aids-epidemic/

Mohanty, C. T. (1991). Under western eyes: Feminist scholarship and colonial discourses. In d. C. T. Mohanty, A. Russo, & L. Torres (Eds.), Third world women and the politics of feminism. Indiana University Press

National Bureau of Economic Research (2002, December 12). The G. I. Bill, World War II, and the education of black americans. The Digest (No. 12). https://www.nber.org/digest/dec02/gi-bill-world-war-ii-and-education-black-americans

Odo, F. (2017). How a segregated regiment of Japanese Americans became one of WWII’s most decorated. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/weekly/edition-150/how-segregated-regiment-japanese-americans-became-one-wwiis-most-decorated/

Rubin, G. (1984). Thinking sex: Notes for a radical theory of the politics of sexuality. In C. Vance, (Ed)., Pleasure and danger. Routledge

State of Oregon (n.d.) World war ii—With mother at the factory…Oregon’s child care challenges. Retrieved December 14, 2023, from https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww2/Pages/services-child-care.aspx

Takaki, R. (2001). Double victory: A multicultural history of America in World War II. Back Bay Books.

TIME (2020). BLM Founders [Video.] https://youtu.be/ddZajib9Z6k

Wells, I. B. (1893). Lynch law. https://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/wells/exposition/exposition.html#IV

Zinn, H. (2003). A people’s history of the United States: 1492-present. HarperCollins.