8.3 Power and Housing Access

Elizabeth B. Pearce, Katherine Hemlock, and Carla Medel

Federal, state, and local governments all influence housing access via laws, zoning rules, permitting processes, and regulations. In addition, the government has the power to regulate the way that most Americans access home ownership, which is a loan agreement between an individual or couple and a lending institution such as a bank or credit union. In fact, it is the lending institution who owns any home, until the individual or couple completely pays the mortgage, which is a combination of the home’s original price and the interest that is charged, typically over a 15-, 20-, or 30-year loan.

Together, government and lending institutions control who can borrow money, where they can access housing, the down payment required, and the interest rate that each family pays. These regulations do not treat all families equally: socioeconomic status, racial-ethnic identity, marriage and sexuality, and immigrant and documentation status have all played a role in lending policies over time in the United States. Immigrants and individuals with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) status have difficulty securing loans due to ambiguous federal legislation affecting their status. People who do not have a social security number are eligible for loans, but these typically require a higher down payment and higher interest rates.

Home foreclosures added to the economic disparity following the housing market crash of 2008. Over half of U.S. states were affected by prior predatory lending practices and lack of oversight of the banking system. Uninsured, private market subprime loans were made available with looser requirements, quickly driving up the price of homes so that some people owed more on their house than it was worth. Many were considered “underwater in their loans” or “upside-down” in their home value and defaulted on payments. Banks took back homes and many families were forced into shelters, living in their cars, or the homes of family members increasing the numbers of cost-burdened, housing insecure, and houseless families.

Affordable Housing

Affordable housing is defined as housing that can be accessed and maintained while paying for and meeting other basic needs such as food, transportation, access to work and school, clothing, and health care. Diverse income levels, reinforced by governmental and lending practices that discriminate based on racial-ethnic groups, immigration status, and socioeconomic status, widen the gap between those who are housing secure, housing insecure, and houseless.

The housing choice voucher program, more commonly known as Section 8 housing, is the federal government’s program for assisting low-income families, the elderly, and the disabled to afford housing. An important thing to notice is how because housing assistance is provided on behalf of the family or individual, participants themselves are able to find their own housing.

Housing choice vouchers are administered locally by public housing agencies (PHAs). The PHAs receive federal funds from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) to administer the voucher program. A housing subsidy is paid to the landlord directly by the PHA on behalf of the participating family. The family then pays the difference between the actual rent charged by the landlord and the amount subsidized by the program. Sometimes, a family could even use its voucher to purchase a home with a PHA’s authorization (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.).

Qualifying for Section 8 housing is not a guarantee of moving into affordable housing. In 2020, the median wait time for people who have applied for a housing voucher in the United States is 1.5 years, with some waits as long as seven years. Currently in Oregon there are 13 open waiting lists and at least seven counties where families cannot even get on a waiting list (Affordable Housing Online, n.d.).

Houselessness

In 2019, over a half million Americans were considered houseless, which means they do not have a permanent place to live. Commonly referred to as “the homeless” or “homeless people” in the past, the terms “unhoused” and “houseless people” are now considered to be more respectful and accurate. This encompasses the movement toward “person-first language” as well as the distinctions between a house, which refers to a physical shelter, and a home, which includes both shelter as well as family, loved ones, or other comforts.

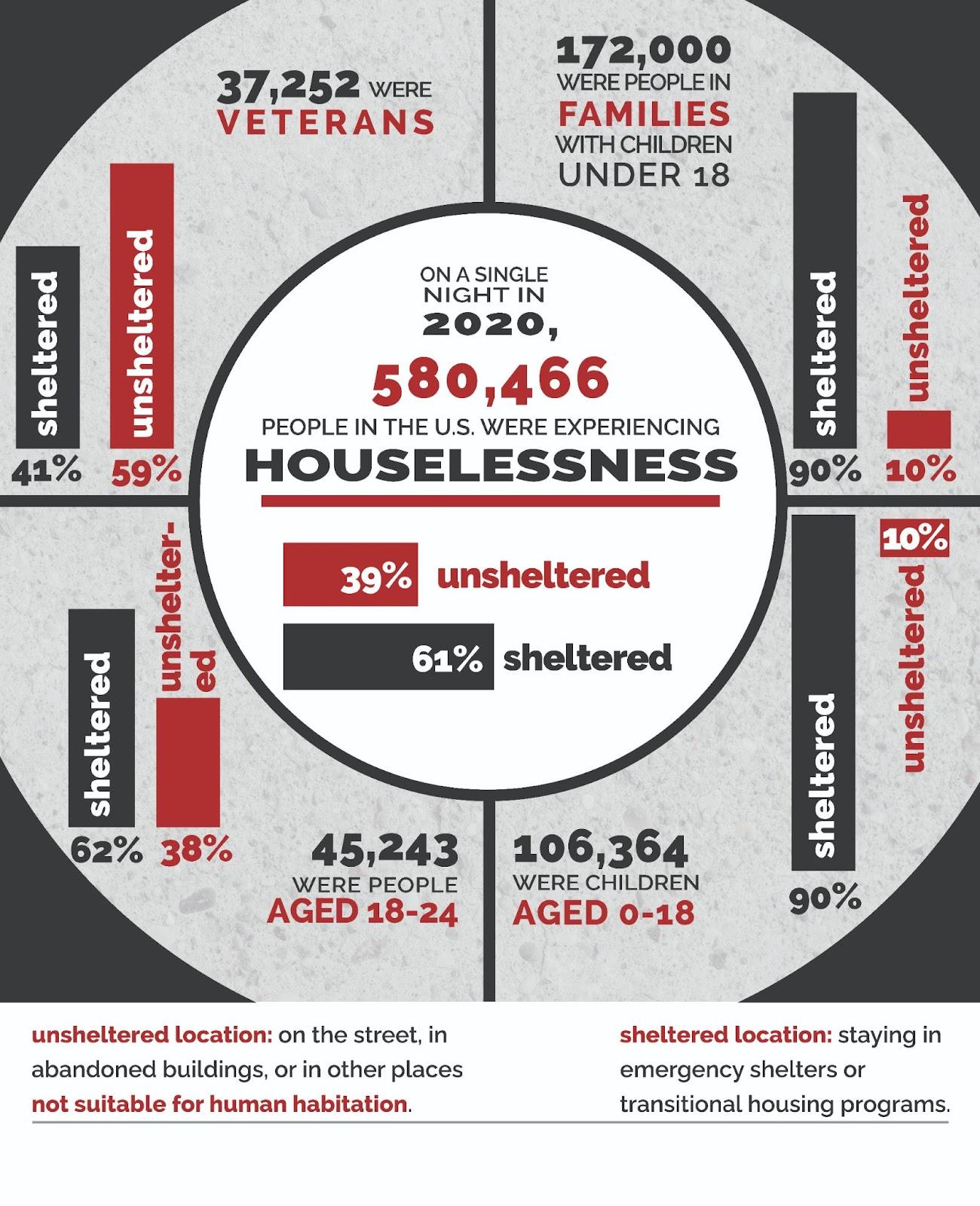

Many of the people lacking housing are children and youth. In early 2018, just over 180,000 people in 56,000 families with children experienced houselessness. More than 36,000 young people (under the age of 25) were unaccompanied youth who were houseless on their own; most of those (89%) were between the ages of 18 and 24 (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2018). In 2020, 580,466 people were experiencing houselessness. The Annual Homeless Assessment Report to the U.S. Congress reports on demographics such as age, veteran status, families with children, and whether people are in sheltered or unsheltered locations while houseless (Figure 8.5).

Figure 8.5. The 2020 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to the U.S. Congress reported about persons who experience houselessness during a 12-month period, point-in-time counts of people experiencing houselessness on one day in January, and data about shelter and housing available in a community.

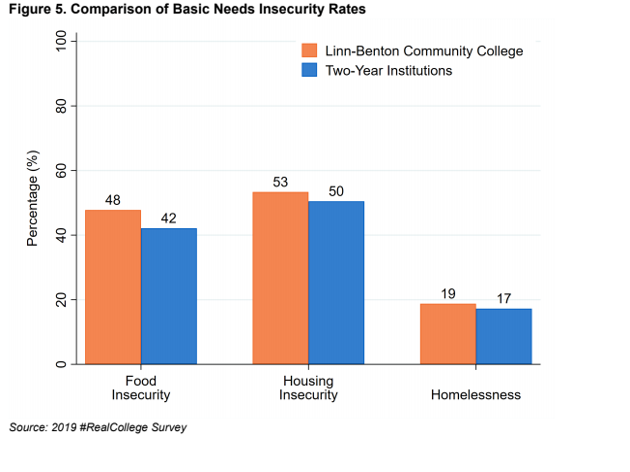

As shown in Figure 8.6, a recent national survey that included Linn-Benton Community College (LBCC) in Albany, Oregon, found that students at the two-year institution had higher levels of houselessness than do their counterparts nationally. With a response rate of 9.7%, 558 of 5,700 surveyed LBCC students participated in the 2019 #RealCollege Survey Report instituted by Temple University in 2019. Nineteen percent of LBCC students reported experiencing houselessness in the past year, compared with 17% nationally. In addition, 53% of LBCC students reported experiencing housing insecurity (described below) in the past year, compared with 50% nationally.

Figure 8.6. A recent national survey that included Linn-Benton Community College in Albany, Oregon, found that students at the two-year institution had higher levels of houselessness than do their counterparts nationally.

This report indicates that more than half of community college students are struggling with some kind of stress related to having a safe, stable place to care for themselves and their families. Demographic factors that indicate a higher rate of houselessness and housing insecurity include being a woman, transgender, Native American, Black, Latinx, or 21 and older. Although White people, men of color, younger students (18 to 20), and athletes were less likely to experience houselessness or housing insecurity, they still did so in double-digit percentages (Goldrick-Rab et al., 2019).

Living in tents, couch surfing and car sleeping all are forms of houselessness. In an effort to provide stability and safety to the houseless population, formal encampments called tent cities have popped up across America in response to the cost of living and other societal problems (Figure 8.7). Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon, provides a community that is self-organized and offers a bit of security. Because the majority of tent cities are not legal, people living in them lack stability and live under the threat of being swept or evicted. In 2017, there were 255 tent cities reported across the United States, ranging in size from 10 to over 100 people living in them. “Of those [tent cities] where legality was reported, 75% were illegal, 20% silently sanctioned, and 4% legal.” Tent cities are a response to the fact that most city-run shelter beds are maxed out and affordable housing has not become available in response to the growing need (Invisible People, n.d.).

Figure 8.7. The Wayne L. Morse federal courthouse is within sight of a temporary location of the Whoville Homeless Camp in Eugene, Oregon.

Temporary Housing

Shelters for people who are houseless provide needed temporary immediate service to over 1.5 million Americans each year (Popov, 2017). Primarily federally funded, many nonprofit organizations also provide support and temporary shelter for families and individuals. Some are so full that they sleep people in shifts, especially in the cold of winter. Many houseless people have nowhere to go during the day; however, day shelters such as Rose Haven in Portland, Oregon, offer services to those in need. The shelter serves about 3,500 individuals, including women, children, and gender nonconforming people who experience trauma, poverty, and health challenges.

Tensions exist among tent dwellers, staff, and users of shelters, and the business and home-owning communities. This is exemplified in Corvallis, Oregon, where the community has struggled for years to find a permanent location for the men’s overnight cold-weather shelter. Advocates for people who are houseless argue for a location close to needed city services; accessibility is important when walking, bicycling, and public transportation are the primary modes of getting around. These needs bump up against business owners’ desires for welcoming environments. Most recently, churches outside of the downtown area have allowed people to erect tents on the church property (Hall, 2019). With the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, more people who are houseless are moving into tents, and the city has intentionally stopped removing illegal campsites. In addition, Corvallis is providing hygiene centers that include showers, handwashing, laundry, and food services (Day, 2020).

The socially constructed ideas of “normal” or “acceptable” identities are barriers to many people in accessing shelter, housing, and other services. In houseless shelters, transgender women may be refused admittance by the women’s shelter and at risk of violence at the men’s shelter. More progress must be made to provide security for all, regardless of identity (National Center for Transgender Equality, 2019).

Another barrier some women with children face in seeking shelter from domestic violence is the shelter rules themselves. Early curfews and overly strict rules can compromise the empowerment of residents. Many women fleeing domestic violence find themselves facing punitive and inflexible environments that mimic the patterns of control they are trying to escape. The Washington State coalition against domestic violence, called Building Dignity, “explores design strategies for domestic violence emergency housing. Thoughtful design dignifies survivors by meeting their needs for self-determination, security, and connection. The idea here is to reflect a commitment to creating welcoming accessible environments that help to empower survivors and their children” (Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence, n.d.).

Housing Insecurity

Housing insecurity is less obvious than houselessness. People who are houseless are somewhat visible, but we may be less likely to know whether or not someone is housing insecure. That’s because it is an umbrella term that encompasses many characteristics and conditions. Signs of housing insecurity include missing a rent or utility payment, having a place to live but not having certainty about meeting basic needs, experiencing formal or informal evictions, foreclosures, couch surfing, and frequent moves (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, n.d.). It can also include being exposed to health and safety risks such as mold, vermin, lead, overcrowding, and personal safety fears such as abuse (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, n.d.). Cardi B’s living situation, which she describes as “practically homeless,” illustrates housing insecurity.

Housing insecurity can be defined as a social problem; the current estimates are that 10% to 15% of all Americans are housing insecure. The increase in the number of cost-burdened households, households that pay 30% or more of monthly income toward housing, is dramatic among families who rent homes. Since 2008, these households increased by 3.6 billion to include 21.3 billion by 2014. And households with the most severe cost burden (paying 50% or more for housing) increased to a record 11.4 million (Harvard University, 2016). By definition, a cost-burdened household is one that also faces housing instability and insecurity.

Somewhere In-Between

A well-established housing system that is often overlooked is immigrant housing. There are many immigrants who come to the United States as part of a guestworker program, which dates back to 1942 with the Bracero Program and continues through the hiring today of H2-A workers. Although these folks are called “guest workers,” they are not treated as guests when it comes to living spaces.

The Bracero Program was an agreement between the United States and Mexico to bring in a few hundred Mexican laborers to harvest sugar beets in California. What was thought to be a small program eventually drew at its peak more than 400,000 workers a year. When it was abolished in 1964, a total of about 4.5 million jobs had been filled by Mexican citizens. After the Bracero Program, foreign workers could still be imported for agricultural work under the H-2 program, which was created in 1943 when the Florida sugar cane industry obtained permission to hire Caribbean workers to cut sugar cane on temporary visas. The H-2 program was revised in 1986 and was divided into the H-2A agricultural program and the H-2B non-agricultural program, which are still up and running today. These programs provide temporary jobs and income for workers but do not offer any advantage in terms of establishing residency or citizenship in the United States.

The protections provided to these guest workers vary depending on the program they are under, so the quality of living varies widely but is often low quality. The housing vicinities lack basic necessities and are often in areas considered to be dangerous. Many guest workers find themselves living in one-room containers that later may be split up between many workers. Other guest workers find themselves living in tent cities, placed right next to the field where they are picking crops. One tent is provided to fit multiple guest workers or an entire family.

These living spaces are often in very rural locations, which isolate these workers and make them totally reliant on their employers. Many employers forbid them from bringing visitors, which reinforces the guest workers’ dependence on the employer and limits the likelihood of reports about the poor living conditions or other violations (Southern Poverty Law Center, n.d.).

Licenses and Attributions for Power and Housing Access

Open Content, Original

“Power and Housing Access” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Katherine Hemlock, and Carla Medel. License: CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.5. By Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi-Hooper. License: CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.6. “Comparison of Basic Needs Insecurity Rates” © The Hope Center. Used with permission.

Figure 8.7. “Whoville Homeless Camp (Eugene, Oregon)” by Visitor7. License: CC BY-SA 3.0.

References

Day, J. (2020, May 4). Corvallis to aid shelter hygiene center. Albany Democrat Herald. https://democratherald.com/news/local/corvallis-to-aid-shelter-hygiene-center/article_d1562ff0-6e81-5914-bfc1-91d9a6d6b89c.html

Goldrick-Rab, S., Baker-Smith, C., Coca, V., Looker, E. & Williams, T. (2019, April). College and university basic needs Insecurity: A national #RealCollege survey report. The Hope Center. https://hope4college.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/HOPE_realcollege_National_report_digital.pdf

Hall, B. (2019, April 10). Corvallis, Benton County homeless council reboot moves ahead. Albany Democrat Herald. https://democratherald.com/news/local/corvallis-benton-county-homeless-council-reboot-moves-ahead/article_d2f33b88-a911-5d29-ba27-77bc499a1dfc.html

Invisible People. (n.d.). How many people live in tent encampments? https://invisiblepeople.tv/tent-cities-in-america/

Joint Center for Housing Studies. Harvard University. (2016, June 22). The state of the nation’s housing 2016. https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research-areas/reports/state-nations-housing-2016

National Center for Transgender Equality. (2019, June 9). The Equality Act: What transgender people need to know. https://transequality.org/blog/the-equality-act-what-transgender-people-need-to-know

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Housing instability. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/housing-instability

Office of Policy Development and Research. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (n.d.). Measuring housing insecurity in the American housing survey. PD&R Edge Magazine. https://www.huduser.gov/portal/pdredge/pdr-edge-frm-asst-sec-111918.html

Popov, I. (2017, February). Shelter funding for houseless individuals and families brings tradeoffs. Center for Poverty Research, University of California, Davis. https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/policy-brief/shelter-funding-homeless-individuals-and-families-brings-tradeoffs

Portland State University. (2019, November 15). PSU’s Population Research Center releases preliminary Oregon population estimates. https://www.pdx.edu/news/psu%E2%80%99s-population-research-center-releases-preliminary-oregon-population-estimates

Southern Poverty Law Center. (n.d.). Guest worker rights. Retrieved February 20, 2020, from https://www.splcenter.org/issues/immigrant-justice/guest-workers

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2018, December). The 2018 annual homeless assessment report to Congress. https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2018-AHAR-Part-1.pdf

U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2019, January). Oregon homelessness statistics. https://www.usich.gov/homelessness-statistics/or/

Washington State Coalition Against Domestic Violence. (n.d.). Building dignity: Design strategies for domestic violence shelter. https://buildingdignity.wscadv.org/