6 Interpreting in Ghana

Daniel Fobi; Joyce Fobi; Obed Appau; and Alexander Mills Oppong

Abstract

The aim of this chapter is to describe signed language interpreting in Ghana. Deaf individuals have over the past 6 decades received diverse forms of interpreting in different contexts, and for different purposes. Various forms of interpreting occur in Deaf communities and other social places like religious meetings, law courts, police stations, television programs, hospitals, and educational settings. Interpreting is offered to deaf individuals from basic schools through tertiary. As the need for best practices in interpreting continues to grow because of the growth in awareness among the Deaf population, there is the need for professional growth in interpreting for the consumers. However, there exist limited documentation of what has transpired over the years in interpreting for Deaf consumers. The professional practices of the interpreters in Ghana is also underexplored. The historical progression of interpreting in Ghana will be discussed. The models of interpreting within which interpreters have operated, the legislative documents which support Deaf individuals, and how interpreting is done and perceived in different communities will be highlighted. The paper will elaborate on the kinds of interpreting that exist in religious, law, hospitals, TV programmes, and educational settings for Deaf individuals. The chapter will also discuss how interpreters are recruited and trained to serve Deaf consumers at various settings. The discussion will focus on some best practices of interpreting in other parts of the world such as Australia, Belgium, Finland, Ireland, Netherlands, U.K., and U.S. and link those practices to what is currently happening in Ghana and make recommendations for Ghana.

Keywords: Best practices; Deaf; interpreters; Legislature; perceptions; sign language

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to discuss signed language interpreting in Ghana. The chapter will describe the historical progression of interpreting in Ghana, forms of signed languages which exist for Deaf individuals and how interpreting is done and perceived in different communities.

Historical progression of interpreting in Ghana

Ghana is an English-speaking country of sub-Saharan Africa. The signed language used by the Deaf community has been developing for over six decades. Since the introduction of formal education for deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) people in Ghana by Rev. Dr. Andrew Foster in 1957, signed language has seen continual development and growth over the years. Foster was a graduate from Gallaudet University who was himself Deaf and aimed at reaching the Deaf community in Africa with the Gospel of Jesus Christ and also to formally educate DHH people. He introduced the DHH to basic literacy and numeracy skills through American Sign Language (ASL), which has later evolved into Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL), a blend of ASL and local Ghanaian signs (Fobi & Oppong, 2018; Oppong & Fobi, 2019). As a pastor, Foster visited homes in Accra to spread the Gospel and also to search for DHH individuals who were over 10 years old. He recruited them into his school, which he had started in his private residence in Accra. During this era in Ghana, there were no systems in place for early identification and management of DHH individuals. So, parents of children who are DHH were the people who could tell whether or not their children were DHH. The parents did this by observing their children, and usually if their children could not talk after age six, they concluded that such children were DHH (Oppong & Fobi, 2019). When Foster arrived in Ghana, parents, siblings, and relatives were people who usually served as interpreters for DHH individuals because of their familiarity with the signs of the DHH family members and their ability to understand what the DHH family members were conveying through their signs. Anytime DHH people came into contact with hearing people and needed to communicate, they would often use gestures or the services of a relative to interpret for them (both DHH and hearing people).

Between 1957 and 1970, Schools for the Deaf were established in the country and different teachers were trained and recruited to support DHH children in the country. The training that teachers of the deaf received at the time and their interaction with DHH individuals familiarized the teachers with the signed language. They used the signed language acquired as a means of supporting the mediation process between the DHH community and the hearing community. They often served as interpreters in Parents Teachers Association (PTA) meetings in schools. Whenever there were events in the communities which involved DHH individuals, the community depended on teachers of the DHH to serve as interpreters. As the years went by and the communities saw the need to integrate DHH individuals into their activities, churches started to provide support services to DHH people. Churches took the initiative to evangelize to individuals who are DHH and brought them to church. What they did by way of communicating with DHH church goers was to write the Bible texts used for their services so that DHH church goers who could read would have access to and follow their sermons. In situations where teachers and relatives who could sign were available for individuals who were DHH, the church used those people as interpreters. In such cases, the church found some incentives for those interpreters and also engaged them in training other people who were interested in signed language so that they could serve as interpreters for the DHH parishioners.

The churches which championed trainings for their members were the Churches of Christ and the Jehovah Witnesses (Fobi & Oppong, 2018). Currently, more churches and Mosques in the country have joined in learning and training of signed language interpreters for their DHH members. In the educational settings, since the exit point for the majority of the DHH students is at the Senior Secondary (Oppong & Fobi, 2019), few DHH students who managed to get into tertiary education prior to the twenty-first century received any form of interpreting. Instead, they had to find their own means of coping with their education without any formal interpreting services provided. It was at the early part of the twenty-first century (i.e., around 2006) that tertiary institutions started recognizing the presence of DHH students and started providing them with some form of interpreting services. In 2006, the University of Education, Winneba, which is the “headquarters” of special education in Ghana, started admitting DHH students and provided some form of interpreting services for the students. The university used the services of final year students (students who were on one-year compulsory teaching internship practice) who, through their training in Education for the Hearing Impaired (EHI) in the Department of Special Education, had some signing skills to serve as interpreters for the DHH students. Occasionally, students who were in the same classroom with DHH students supported their DHH colleagues whenever their interpreters were absent. This kind of service provision continued for the DHH students until the year 2013 when the university officially recruited its first batch of fulltime interpreting staff. Interpreters who work in this university out of their experience with the DHH students continue to improve the services they provide but have not acquired any form of professional certificate to serve as interpreters. It must also be noted that, in Ghana, there is no professional body in charge of certifying interpreters.

Since the year 1968, when the Ghana National Association of the Deaf (GNAD) was formed to bring together the Deaf in Ghana and to serve as an advocacy group for the deaf, they have worked tirelessly to provide some form of support and training for their members by engaging and training more interpreters. Currently, GNAD has a catalog of interpreters across the various 10 Regions of Ghana (now Ghana has 16 regions but the catalog reflects the old regions), who they recognize. GNAD uses their services any time they interpreters are required.

Paradigms of Signed Language Interpreters

Interpreters who serve DHH individuals continuously work in different paradigms. For most of them, the paradigms they work in mostly depend on how they were first recruited and the setting where they work. Due to the nature and how interpreting has emerged in the country, most signed language interpreters are family members, church members, and classmates of DHH people. This association with the DHH people often makes the majority of interpreters feel DHH people need help since they are not able to advocate for themselves because of the communication difficulty they presume DHH people have. Such interpreters with this kind of motivation often work as “aid givers” and “helpers” for the DHH individuals. Interpreters who served DHH consumers using this particular paradigm of interpreting often have no formal training in interpreting and are often not remunerated (Frishberg 1986; Wilcox & Shaffer, 2005). The majority of interpreters who serve in this paradigm in Ghana are People from Deaf Families (PDFs, commonly referred to as Children of Deaf Adults, or CODA; see, for example, Napier & Leeson, 2016), neighbours, church members, friends, and classmates who often come in to support DHH individuals whenever there are communication difficulties emerging for DHH people. Often since most interpreters believe DHH people cannot be independent without their support, the interpreters often accompany them to places like churches, banks, hospitals, police stations, court rooms, and sometimes even to schools. Such interpreters in Ghana do almost everything for DHH individuals, by trying to “educate” and “convince” hearing people on the “inefficiencies” for the DHH people. In the school settings, interpreters who operate in this paradigm wish they were given the opportunity to do assignments and even write exams for DHH individuals. Interpreters who often operate in this paradigm advocate for helping DHH individuals in an admirable way since they think that without them DHH individuals could not survive on their own personal, social, and professional businesses (Roy, 1993, 2000).

Another group of Ghanaian interpreters who believe that interpreting is a profession, view themselves as professionals and operate in a different paradigm of interpreting for DHH consumers. Though there is not professional body in charge of the training and certification of interpreters. These interpreters often do not want to align with one particular cohort of consumers (i.e., the hearing or DHH individuals) and as such often prefer to work as people who are “invisible” in the interpreting process. Those interpreters often operate in a paradigm referred to as the “machine” or “conduit” paradigm. Since the establishment of the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) in 1964 in the United States of America (USA), interpreters began to critically assess the interpreting process and their role as interpreters (Wilcox & Shaffer, 2005). Interpreters’ critical analyses of their role brought about the need for them to be viewed as invisible in the interpreting event and they worked much like machines. This paradigm suggested that interpreters should be nothing more than a conduit for communication; that interpreters should remain emotionally and personally detached from the interpreting situation. Interpreters who go by this paradigm only act as amplifiers whose role is solely to re-echo what is said in spoken languages to signed language and vice versa. They do not necessarily focus on encoding source messages and ensuring the same meaning and value of content are maintained when the messages were converted into the other language (spoken or signed). Wilcox and Shaffer (2005) explained that this paradigm has made interpreters alienate themselves from both the hearing and Deaf communities during the interpreting process. Interpreters who adopt this paradigm often do not socialize with DHH people because they think their role basically is to interpret and anything exceeding that is classified as unprofessional. Interpreters who support this paradigm advocate that interpreting programmes should ensure that they include some self-discipline in order to aid interpreters consciously detach themselves, staying neutral, impersonal, and objective in the execution of their duties (Quigley & Youngs, 1965; Wilcox & Shaffer, 2005). The interpreter’s role as communication conduit has been explained as,

The sign language interpreter acts as a communication link between people, serving only in that capacity. An analogy is in the use of the telephone – the telephone is a link between people that does not exert a personal influence on either. It does, however, influence the ease of communication and speed of the process. If the interpreter can strive to maintain that parallel positive function without losing vital human attributes, then the interpreter renders a professional service. (Solow, 1981, p. ix)

To consider interpreters in interpreting as “invisible” and to act as machines implies that interpreters do not exist and their contribution to the communication process should not be recognised. Some interpreters in the country argue that though it is necessary for interpreters to be professionals, there is the need for them to be assertive in their roles. This kind of argument makes some interpreters who have received some form of formal training and have acquired skills to operate using the communication facilitator paradigm. In the communication facilitator paradigm, interpreters advocate for the need for interpreter education and training to be a vital part in advancing the profession to see interpreters as individuals who have specific communication roles and responsibilities (Gish, 1990; Trine, 2013). Interpreters who operate within the communication facilitator paradigm, often have pre-assignment meetings with their consumers and discuss with them what their roles, responsibilities, and expectations are from their consumers in the interpreting process (Trine, 2013). Ingram (1974) proposed this paradigm. In his exposition on the paradigm, Ingram explained that there is the need for interpreters to be more assertive in their role: explain to hearing individuals what their roles are, arrange seating/lighting, exert control over the environment, and take responsibility to meet the DHH consumers prior to beginning their assignments. Ingram explained that this paradigm was meant to “define the interpreting process in a scientific manner and suggest implications for examining various aspects of interpreting within the framework of that model” (Ingram, 1974, p, 1).

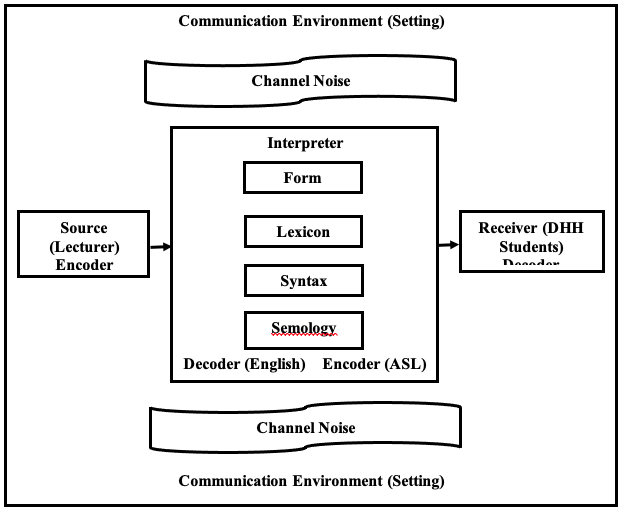

In the communication facilitator paradigm, Ingram (1974) suggested four major critical contributors of an effective interpreting process. The four were the source (encoder or decoder), channel/interpreter (decoder and encoder), receiver (decoder or encoder), and the communication environment (setting). Figure 1 gives a diagrammatic view of Ingram’s model. He viewed signed language interpreting as a communication process and as such each of the four key variables play active roles in the process. Ingram highlighted how the process of interpreting should be by stating that,

When the hearing person speaks his message in English, the interpreter must decode the message from its spoken symbols to determine the thought embodied in those symbols and then encode the message once more into the visual symbols of the language of signs. The deaf person must then decode these visual symbols to arrive at the meaning of the communicated message. (Ingram, 1974, p. 2)

Although Ingram acknowledged that different stakeholders contribute to an effective interpreting process, he did not spell out the specific roles of each member in the process.

Figure 1

Communication Binding Context (adapted from Ingram, 1974)

Also, some interpreters work on the assumption that language and culture are inseparable and for interpreters to conveniently mediate between DHH individuals and their hearing interlocutors, the interpreters need to understand and know how to work between the cultures of their consumers. Interpreters who work with this assumption employ the bilingual bicultural (Bi-Bi) paradigm. Interpreters who employ this paradigm of interpreting assume the responsibility of mediating between languages and cultures; between hearing and DHH interlocutors whilst helping the speaker to achieve their goals in communication (Humphrey & Alcorn, 2001). Wilcox and Shaffer (2005) explained that Etilvia Arjona, a spoken language interpreter proposed the Bi-Bi model but it was Ingram, a signed language interpreter, who stressed that “language” and “culture” were inseparable. Roy (1993) added that the interpreting process is considered to occur in a situational/cultural context which forms part of the process. Roy added that it is important to consider the cultural context so that the gap that separates the sender and the receiver will be bridged. This paradigm allowed for signed language interpreters to take the responsibility for the exact transmission of communication by asserting the need for interpreters to mediate not only between two languages, but also two separate and very distinctive cultures.

Another paradigm that interpreters operate in is the Ally paradigm. This paradigm is often used by interpreters who work in educational settings (Wilcox & Shaffer, 2005). Interpreters who work using this paradigm insist that they are no longer responsible for pushing for the rights of DHH individuals, but rather lend themselves as an ally to their clients (both hearing and DHH), letting them know that the interpreter would accurately convey anything they wish to say. This paradigm endeavoured to avoid the inadvertent oppression of the DHH individuals. It is important to note that this paradigm assigns some responsibilities to each of the parties involved in the interpreting process particularly the hearing and DHH consumers, and the interpreter. In this paradigm, interpreters should see the DHH client as experts of Deaf Culture and signed language. It also important to add that the interpreter should allow the client to advocate for themselves whenever needed and their role as interpreters is to be responsible for providing accurate interpreting. The positive side is the attempt to empower the participants in the communication to advocate for themselves, while the interpreter still takes responsibility for the accuracy of communication. This paradigm allows interpreters to best decide the way to communicate a message in order to transfer the content meaning without necessarily interpreting whatever they hear/see.

The final paradigm that very few interpreters operate in is the progressive or “sore thumb” paradigm. Basically, this paradigm shows the evolution of the interpreter as a professional by following the same path that the profession has taken. Young student interpreters enter following the Helper paradigm (most often), viewing d/Deaf individuals as people in need of assistance. After graduation from interpreter training programmes (ITP), the young professional now enters a stage based entirely upon their ethics, or the conduit/machine paradigm. As the interpreter gains more years of experience, they progress to more accurate communication facilitator paradigm. Finally, they plateau as seasoned professionals using the communication, Bi-Bi, and Ally paradigm depending upon the situational needs.

Legislation supporting interpreting in Ghana

This section provides information on legislation supporting interpreting in Ghana. Generally, special needs education for persons with disabilities including DHH individuals and inclusive education is backed by legislation. However, the legislations are yet to be actively instituted and enforced. However, the Persons with Disability Law (ACT 715) of Ghana, which has 60 sections, was passed on August 9, 2006. The Act gave recognition to the teaching of signed language in colleges of education. The Act makes it a legal offense punishable by ten penalty units (a unit is GH₡ 12.00) or fourteen days imprisonment for any parent who refuses to enroll their school-age children in a school. It also makes it an offense for any head of public educational institution to refuse to enroll a school-age child on the grounds of disability such as deafness. However, since Ghanaian Sign Language (GhSL) is not officially recognized in the country, there is no specific legislation supporting interpreting.

Forms of signed language that exist in Ghana

Ghana has three different signed languages, the Ghanaian Sign Language (GhSL), Adamorobe Sign Language (AdSL) (see Edward & Akanlig-Pare, this volume), and Nanabin Sign Language. Ghanaian Sign Language is language used by the majority of DHH individuals in Ghana (Fobi & Oppong, 2018). It is also the language used as medium of instruction for schools for the Deaf in the country. Foster used ASL as medium of instruction in the schools for the Deaf he started in Ghana in 1957. With time, the Ghanaian deaf people combined their local signs and ASL, so GhSL is made up of ASL and local signs. Although it has not been officially recognised as the language of Deaf people in Ghana, GhSL continues to be the most common language for the majority of Ghanaian Deaf people. In some parts of Ghana, there are slight differences in the formation of some signs of GhSL, but these differences do not take away the fact that deaf people who have acquired GhSL from one part of the country can communicate with a person who is Deaf who has learned GhSL from another part of the country. The variations in some of the signs in GhSL is often due to hearing people (usually, hearing teachers) who have acquired the language. The teachers often use their own created concepts in place of concepts that are not familiar to them. Again, based on the geographic location of Deaf people, their sign for some concepts may differ from some signs used by Deaf people from another part of the country.

The next signed language widely used by deaf individuals is in a community called Adamorobe in the Eastern Region of Ghana and is AdSL (see Edward & Akanlig-Pare, this volume). Adamorobe is a small community with a population of about 1400 which has a large number of Deaf individuals (Nyst, 2007, 2010). There has been a high incidence of hereditary hearing loss among some generations in this community. The Deaf people in the community have their own local signed language, AdSL, for communicating. AdSL is totally different from GhSL.

Also, in the Central Region of Ghana, there is a small village called Nanabin. Nanabin has a family which has three generations of deaf people (Nyst, 2010). That family has about 26 members who have their own way of communicating through signed language; the name of this signed language is Nanabin Sign Language (NaSL). Although NaSL and AdSL have some common features in their expressions, they are set apart from each other since knowledge in one of them will not enable one to communicate in the other (Nyst, 2010).

Perceptions of interpreting in different communities

Within different communities, in Ghana, interpreting is perceived differently. Amongst the local indigenous people, they are of the view that having a deaf child or being a PDF should automatically equip them with the skills and knowledge relevant to interpret. This kind of understanding often makes people think that, even without any form of training and certifications, interpreters can conveniently interpret for their consumers. Also, because of their cultural beliefs and superstitions, some people stigmatize interpreters across various communities in Ghana. Some people believe that deafness is contagious and that the ability to sign will likely result in giving birth to deaf children. This makes many parents discourage their children from associating with deaf people and learning signed language.

In the religious settings (often churches and mosques), people stress the need for people to learn signed language so that the word of God could be provided to Deaf people. They think that, being able to win a Deaf person’s soul for God is often worth more than about 50 hearing souls for God (Clergy in Ghana, personal communication, 2016). As a result, religious organizations encourage the learning of signing and promote the activities of Deaf people so that Deaf people can be fully integrated into the religious communities. Some religious bodies especially the churches, have trained interpreters who serve Deaf people at their gatherings. Others have even trained some deaf people to be preachers, evangelists, and pastors. Often interpreters who visit religious gatherings are regarded as people with high levels of intelligence and skills who are often respected and given special treatments.

Interpreting in educational settings is done on different levels (basic through tertiary) of education in the country. Often it is in inclusive settings that interpreters are available. As part of the goals of inclusion, hearing students with deaf classmates often learn signed language and are able to communicate with their peers. Because of this, some people are of the view that such students should be used as interpreters without any form of remuneration or support. Some institutions do not see the need to hire and pay interpreters to support deaf students and this often leads to an inadequate number of interpreters in inclusive schools. Other institutions, mostly at the tertiary level, have tried to employ permanent interpreters and some part-time interpreters to support DHH students. A section of the community in education think that being able to interpret means that the interpreters have high level intelligence quotient (IQ) and such people regard interpreters in high esteem because they think interpreting is an art which requires high levels of knowledge and skills. Often, people in this community especially students and teachers, want to engage some individuals to learn signed language so that they can also communicate directly with DHH students. Another section of the educational community does not think interpreters should be given any special treatment. This group of people regards interpreting as a waste of time because they believe that since DHH students have literacy skills, there is no need for any form of mediation. Even though people’s perceptions about interpreting continue to change with time because of education and awareness about DHH people, there still exists a group of people who hold on to the primitive idea that Deaf people are dependent on hearing people and cannot learn on their own.

Types of interpreters working in religious, law, hospitals, TV programmes, and educational settings

Different types of interpreters exist for DHH individuals in Ghana. In communities like Adamorobe and Nanabin, often family members of the Deaf community who have acquired both GhSL and (either NaSL or AdSL) serve as interpreters. The majority of interpreters in those communities are PDFs who have also had the opportunity of formal education in GhSL. They serve as interpreters whenever there are Deaf visitors to the community. Those interpreters are often Deaf themselves. Another form of interpreting which exists for local PDFs is from the AdSL or NaSL to local spoken language (often Akan). Anytime there are hearing visitors to the towns, the PDFs interpret for the deaf in the community and also for the visitors. Often if the interpreter serving in this community has had some formal education and can communicate in English, they often do the interpreting between the AdSL or NaSL and English. In situations whereby the interpreters cannot communicate in English, they often use a third person who is conversant with the local spoken language and English to do secondary interpretation.

In places where GhSL is used, interpreting is often done between the GhSL and English or the spoken language being used at the time. Settings including religious, legal, and hospitals often have interpreters mediating between local spoken languages and GhSL. On TV and educational settings, often interpreters serve between GhSL and English. In most cases in religious, legal, and hospital settings, there are no signed language interpreters available, so people use gestures and sometimes write in case the Deaf person is literate in order to communicate. In most of the formal settings (health, education, legal), there are no permanent interpreters available, so interpreters are called upon when their services are needed. On TV, it is only the Ghanaian Television (GTV) and Amansan Television (ATV) that have some permanent interpreters. For the most part, they interpret the evening news and national events. Even on those stations, the size and position allocated to the interpreters on screen often makes it difficult to see the hands and signs of the interpreters clearly.

Recruitment and training of interpreters in various settings

Different settings have different ways of recruiting and training signed language interpreters. With regards to the recruitment, often it is People from Deaf Families (PDF) who by virtue of having Deaf family members decide to learn signed language and eventually end up as interpreters. Some interpreters also acquire the language naturally because their parents are Deaf and are then recruited into the interpreting field. At religious settings, often announcements are made for interested people to come up to be trained to serve as interpreters for Deaf members. Again, some interpreters attend same schools with Deaf people and learn signed language in the course of their study and end up as interpreters. The Ghana National Association of the Deaf (GNAD) also organises and trains interpreters to support the Deaf community in Ghana. At educational settings, the majority of interpreters have had some training from the Education for the Hearing Impaired (EHI) of the Department of Special Education, University of Education, Winneba (UEW). The majority of students who receive their training from the EHI end up with some signing skills and eventually end up serving as signed language interpreters.

Conclusion

Globally, signed language interpreting has seen a face lift. Through advocacy of Deaf communities, different countries have recognized and accepted signed languages as formal languages and modes of communication for Deaf individuals. These recognitions of signed languages also push for the need for interpreting to be promoted in every country where Deaf individuals exist. Although interpreting has been in existence for Deaf and hard of hearing individuals since the formal initiation of signs into educational systems (Fobi & Oppong, 2018), many people have still not recognized interpreting services. Many are of the view that interpreting as many will refer to as “signing” is a free service that is often rendered by children, classmates, and church members with relationships to Deaf people. The providers of interpreting services (interpreters) in most of the cases think they are aid givers who provide some aid to Deaf individuals to facilitate their communication. In Ghana, there are mixed reactions toward what interpreting service is, and whether or not that service should be seen as a profession; this has been an ongoing debate among various stakeholders of the services.

References

Fobi, D. & Oppong, A. M. (2018). Communication approaches for educating deaf and hard of hearing (DHH) children in Ghana: Historical and contemporary issues. Deafness & education international, pp.1-15.

Frishberg, N. & Barnum, M. (1990). Interpreting: An introduction. Silver Spring, MD: RID Publications.

Gish, S. (1990). Ethics and decision making for interpreters in health care settings: A student Manual. Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN: The College of St. Catherine.

Ingram, R. M. (1974). A communication model of the interpreting process. Journal of rehabilitation of the deaf, 7(3), pp.3-9.

Kusters, a. (2015). Deaf space in Adamorobe: An ethnographic study of a village in Ghana. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Napier, J. & Leeson, L. (2016). Sign language in action. In Sign language in action. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Nyst, V. (2007). A descriptive analysis of Adamorobe Sign Language (Ghana). Utrecht: Lot.

Nyst, V. (2010). Sign languages in West Africa. In D. Brentari (ed.), Sign languages: A Cambridge Language survey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oppong, A. M. & Fobi, D. (2019). Deaf education in Ghana. In H. Knoors, M. Marschark, & M. Brons (eds.), Deaf education beyond the western world – context, challenges and prospects for agenda 2030. Oxford University Press.

Quigley, S. P. & Youngs, J. P. (1965). Interpreting for deaf people. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Roy, C. B. (1993). A sociolinguistic analysis of the interpreter’s role in simultaneous talk in interpreted interaction. Multilingual-journal of cross-cultural and interlanguage communication, 12(4), pp.341-364.

Roy, C. B. (2000). Innovative practices for teaching sign language interpreters. Washington DC: Gallaudet university press.

Trine, E. (2013). A Case Study of an Arabic/Jordanian Sign Language (LIU) interpreter in Jordan (master’s thesis). Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/10/

Wilcox, S. & Shaffer, B. (2005). Towards a cognitive model of interpreting. Benjamins translation library, 63, p27.