1.3 Theories, Practices, and Concepts Central to Human Services

The introduction to this section is based on the work of Aika Fricke while she was a candidate for her MSW at Ferris State University (figure 1.5).

Aika Fricke has worked for Community Mental Health for Central Michigan since 2008 as a clubhouse advocate, case manager, and most recently as an employment specialist. She is a full-time mother to “four lovely children and a full-time wife to a wonderful and very supportive husband, as without his tremendous support furthering my education would not have been possible.”

Human services professionals take a generalist approach, which means they use their broad knowledge across many disciplines and methods to solve problems. An advantage of the generalist approach is the awareness of theories, foundational concepts, and practices of multiple fields and practitioners that promote well-being. A generalist approach introduces students to the application of addressing social problems at the individual (micro), group (mezzo), and community (macro) levels while following ethical principles and critical thinking (Inderbitzen, 2014). Generalist human services workers in a helping profession use a wide range of prevention, intervention, and remediation methods when working with families, groups, individuals, and communities to promote human and social well-being (Johnson & Yanca, 2010).

Being a generalist practitioner prepares you to enter nearly any profession within the human services and social work fields, depending on your population of interest (Inderbitzen, 2014). You may develop a specialty within the generalist approach during your education, internships, or professional life. For example, the program director for people experiencing homelessness would apply their generalist knowledge to a specific population: those who have housing insecurity or are houseless. A medical social worker would apply their broad knowledge to a specific group of people hospitalized at a cancer center.

Why Theories and Research Matter

Have you ever wondered, “Why is my three-year-old so inquisitive?” or “Why are some fifth graders rejected by their classmates?” or “Why do some people become addicted to alcohol and others do not?” Theories can help explain these and other occurrences. Theories offer possible explanations about how we develop, why we change over time, and what kinds of influences impact development.

A theory guides and helps us interpret research findings as well. It provides the researcher with a blueprint or model to help piece together various studies. Think of theories as guidelines, much like directions that come with an appliance or something that requires assembly. The instructions can help you piece together smaller parts more easily than you would using only trial and error. There are many theories of development. In this book, we have chosen to draw on many theories, several of which are summarized in this chapter.

Ecological Systems Theory

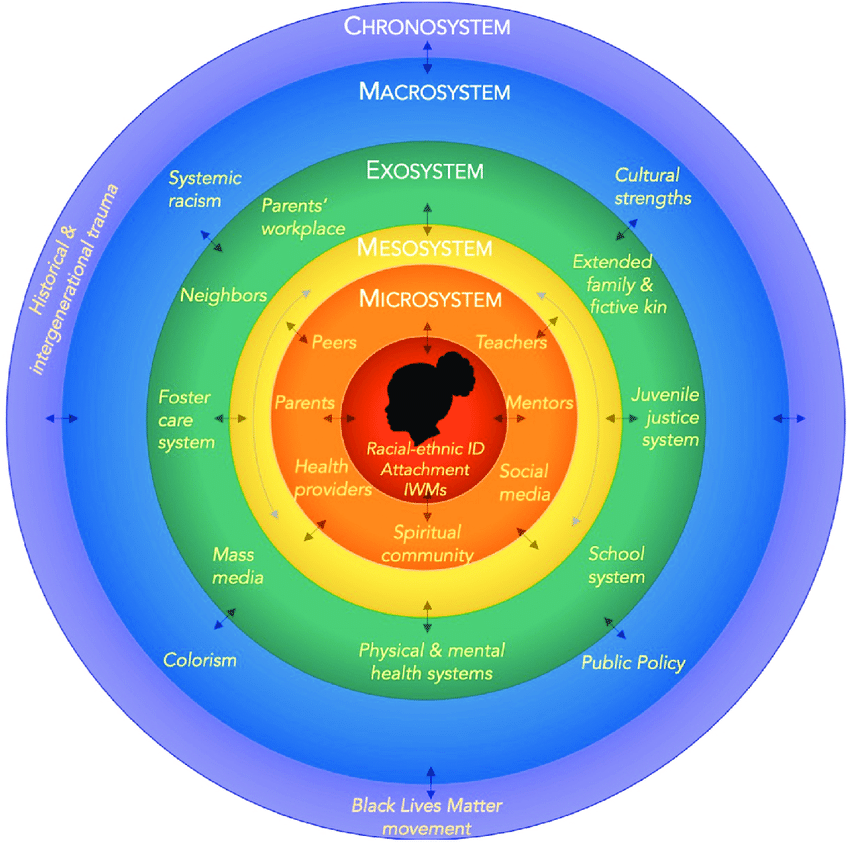

Ecological systems theory is an interdisciplinary study of complex systems that focuses on the dynamics and interactions of people in their environments (Kirst-Ashman & Hull, 2015). Professionals use this theory to identify, define, and address problems within social systems.

Ecological systems thinking helps us understand the relationships between individuals, families, and organizations within our society. It is used to identify how a system functions and how the negative impacts can affect a person, family, organization, or society as a whole. The same information can be used to identify strengths and to cause a positive impact within that system (Flamand, 2017).

The ecological systems theory was developed in the late 1970s by Urie Bronfenbrenner. It draws on systems theory and an environmental approach known as person-in-environment. This approach asserts that individuals are influenced by their surroundings. However, some critics argue that the model places too much emphasis on the biological and cognitive aspects of human development and that it should include more on the socioemotional element of human development.

The ecological systems theory emphasizes the complexity of the environments and systems that each individual interacts with. In helping professions, professionals support clients and community members in identifying what is working well and what is negatively impacting them within multiple systems and environments (figure 1.6).

To illustrate this theory and the following theory, we will use this vignette about “Marlene.”

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

Marlene has been working with the school social worker because she has been crying during class for multiple days during the past few weeks. After talking for a few minutes, Marlene describes having a recent fallout with her social group, which is mostly made up of her Black friends. As a child of a multiracial family–a Black mother and Korean father–she reports having difficulty authentically relating to any group and being stereotyped as exotic. Marlene says her parents are supportive and talk to her often about her mental health, though she has more conflict with her step-siblings. She says she feels more overwhelmed than ever and needs help knowing what to do next.

Microsystem

The ecological systems theory is typically illustrated with six concentric circles that represent the individual, environments, and interactions (figure 1.6). The microsystem is the smallest system, focusing on the relationship between a person and their direct environment, typically the places and people that the person sees every day. Often, this includes parents and school for a child or partner, or work and school for an adult.

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

Marlene’s family is one of the primary sources of both support and anxiety for her. Her parents were concerned in her middle school years when she had trouble making friends, but they were very encouraged when she found a close group of friends in high school. A teacher she is close with saw the argument Marlene had with her friends and suggested she talk with a social worker to help her feel better.

Mesosystem

The mesosystem, which lies between the micro and exo systems, represents how those people and places interact and cooperate. If they work together well, it can positively affect the individual. For example, if a student also has a job, is the employer willing to work around the school schedule? If a child attends a childcare program, do the teacher and the parent communicate clearly? The mesosystem is important because it is about the relationships and the interactions among important environments.

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

The family moved to this city about three years ago. Previously, Marlene’s family lived in Arizona, along with her extended family. Marlene talks about having more connections with her community in Arizona, including a spiritual community and a local community of musicians. When they moved, Marlene lost these connections, as did her family. Although her parents make more money than they did in their previous city, they are away from home a lot more and have less time to spend with Marlene.

Exosystem

The exosystem includes the people and places that an individual interacts with regularly but not daily, such as a place of worship, club, lesson, or social group.

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

Marlene was also recently injured while on a trip with the marching band, in which she plays the trumpet. Because the trip was in a different state’s hospital network, her parent’s medical insurance did not cover her care. The bill was over $10,000, placing additional financial strain on the family. Marlene’s new school is also predominantly White students, and she sometimes suspects teachers are harder on her than other students. Marlene’s relationship with her extended family is maintained via video chat, except for their annual trip for a family reunion in Arizona every summer.

Macrosystem

The macrosystem identifies the larger values and attitudes of the culture and varies by location and interest.

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

Marlene’s struggle with racial identity is mirrored in our larger culture’s struggle with its racialized history and present inequities. The discrimination that Marlene faces is a product of historical oppression. Similarly, her family’s struggle with health insurance and financial precarity is common in our culture, though more common among minoritized racial and ethnic groups.

Chronosystem

The chronosystem describes time as a system that affects individuals. Large events and trends—such as the dramatic increase in college costs and debt, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the frequency of record-setting wildfires on the West Coast of the United States—are all examples of events in the chronosystem that affect individuals and families in the first part of the twenty-first century.

Stories from Human Service Work: Marlene

Many adolescents have reported increases in depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s possible that Marlene has been affected or that her family may have had trouble adapting to the crisis. It is important to consider large socio-cultural events and their effects on individuals. The chronosystem helps us understand how Marlene’s struggles with racial identity development are impacted by present-day events and compare them with previous generations’ struggles. Although Marlene’s chronosystem enables her to keep in contact with extended family in her previous city, her identity also makes her online life more vulnerable to abuse and harassment.

Evidence-Based Practice

Evidence-based practice (EBP) is not simply “doing what the literature says.” It is a process that human service workers engage in with their clients. The bedrock of EBP is a proper assessment of the client or client system (such as a family or social group). Once we have a solid understanding of what the issue is, we can evaluate the literature to determine whether there are any solutions others have found to be effective. If this sounds familiar, that’s because it’s the same approach a doctor, physical therapist, or other health professional would use. Evidence-based practice prevents workers from using quack interventions that are not based in science.

Drisko and Grady (2015) define EBP as being composed of “four equally weighted parts: 1) client needs and current situation, (2) the best relevant research evidence, (3) client values and preferences, and (4) the clinician’s expertise” (p. 275). A human service worker uses their skills in engagement and assessment to talk with clients, identify their issues, and collaboratively decide on evidence-based approaches to the client’s goals.

EBP is situated within an agency context. As depicted in figure 1.7, evidence-based practice is also impacted by the resources available to the clinician at their human service agency—the “clinical context” in the diagram. Some agencies specialize in one type of treatment that they perform for all clients (e.g., 12-step addiction recovery, kidney dialysis), while others may use multiple EBPs or work on teams that develop new EBPs not yet in the literature.

Social science allows workers to test their ideas about how to help people using the scientific method. Publishing those results allows others to build knowledge within a scientific community. Historically, the scientific community has excluded people from the Global South, indigenous communities, women, people with disabilities, and other oppressed groups. This biases the scientific literature towards people who speak and write English, access scientific articles via well-funded university libraries, and purchase the laboratory, software, and other resources needed to produce new scientific discoveries.

Because social science in part tries to establish truths applicable to all humans, problems arise when researchers make general statements about all people based on studies that almost always use participants from Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic (WEIRD) countries. These studies incorrectly classify participants as “standard subjects” and exclude researchers and participants from less developed countries (Henreich et al., 2010). Arnett (2008) found that 70 percent of the people studied in prominent psychology journals were from the United States alone, and a 2020 reanalysis found that 89 percent of the world’s population is not represented by the cultures studied in psychology journals (Thalmayer et al., 2020).

Even when diverse samples are assessed by social scientists, across history and today, scientists extract data and publish it without regard for the long-term impact on communities or respect for the traditional knowledge practices of Indigenous people (Smith, 2021). Another limitation in the scientific literature is that EBP studies often isolate a single diagnosis or issue. A study investigating treatments for major depressive disorder (MDD) may be less helpful if you are helping someone from a different culture than yourself who also has MDD, autism, and a physical disability.

The scientific literature does not contain the One True Answer to a problem, and human service workers must use their critical thinking skills to link data and practice. You should stay abreast of new research when working with clients and implementing evidence-based practices. At the same time, pay attention to practices used by BIPOC communities over centuries of use, such as meditation. Whether or not these practices have been researched and have produced formal evidence, the long-time use of these methods is itself another kind of evidence. Make sure to engage with sources of evidence beyond science, such as what your clients and communities center on when making decisions.

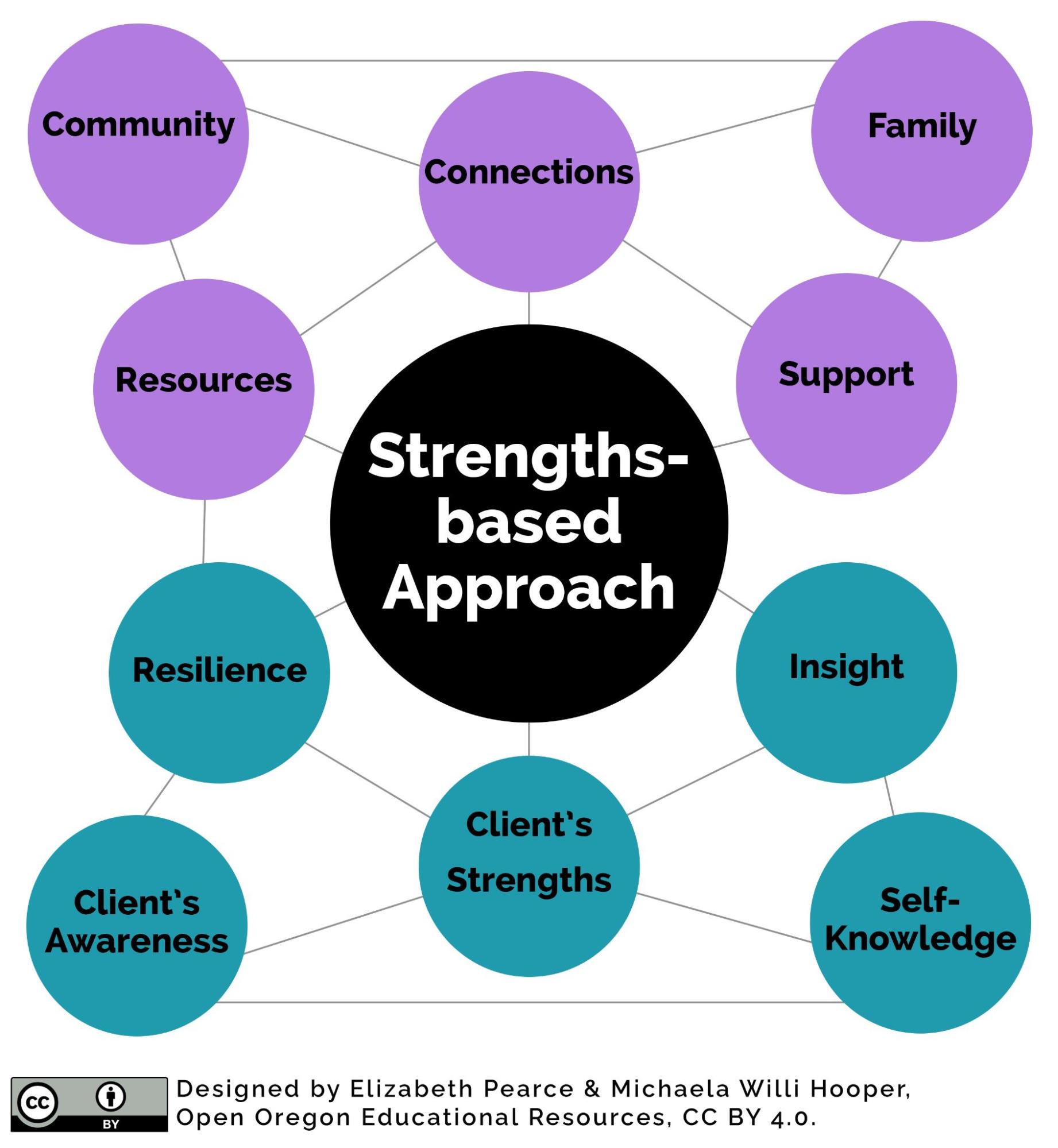

Strengths-Based Approach

The strengths-based approach, also known as the strengths perspective, emphasizes that every person, group, family, and community has strengths, and every community or environment is full of resources (Johnson & Yanca, 2010). Often attributed to Bertha Reynolds, a mid-twentieth-century social worker, and Dennis Saleebey, a late-twentieth-century scholar, the approach has a foundation in the work of Black scholars and social workers. W. E. B. Du Bois wrote about the strength of Black people in adapting to and surviving in hostile conditions. In the early twentieth century, Black social workers such as Birdye Henrietta Haynes, Elizabeth Ross Haynes, and others focused less on pathologizing Black people and more on the strengths and resilience strategies found within families and communities (Wright et al., 2021).

When using the strengths approach, not only is the human services professional or social worker helping the client to identify their personal strengths, but the worker is also helping the client identify local resources to help the client’s needs. There are many things to keep in mind, as figure 1.8 illustrates. This approach focuses on the strengths and resources the client already has rather than on building new ones.

Cultural Responsiveness

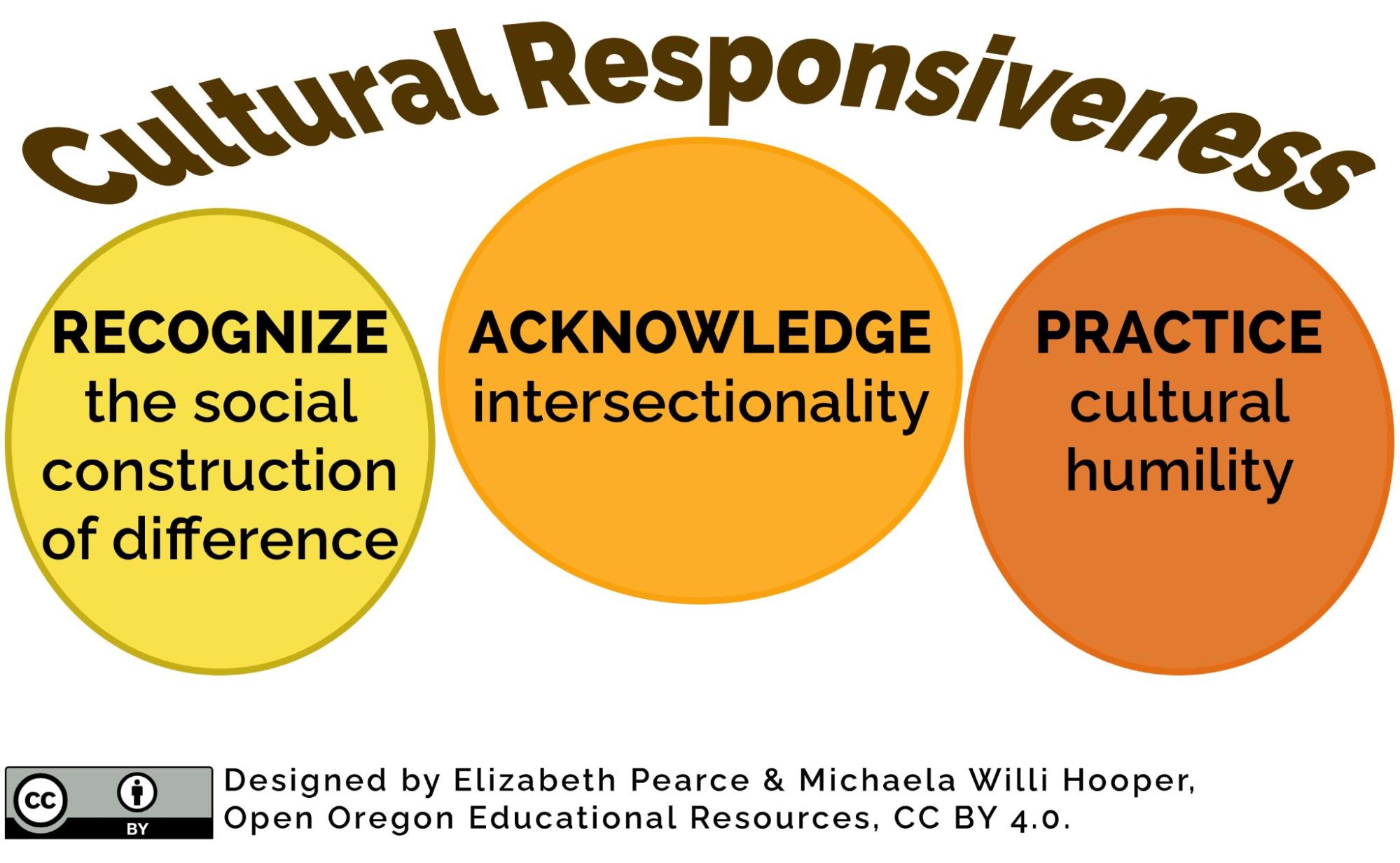

Cultural responsiveness, also known as a culturally responsive approach, involves being aware that each individual you meet has their own set of beliefs, values, routines, and rituals that contribute to their culture.

Cultural responsiveness means being aware of cultural factors and appropriately responding to them, as described in figure 1.9. As a human services professional, learning about cultures is a part of your job. You can learn about culture specifically from that culture’s members but do not expect people from marginalized groups to do all the work of teaching you. Read, listen, and watch media sources created by, rather than for, members of a culture. Culturally responsive human services workers include culture as part of their assessments. They tailor their interventions to consider the client’s culture and the effects of oppressive systems.

People are the experts in their own lives. To be truly client-centered, professionals must remember what a person’s values are and their preferences for the outcome of their life situation. It can be tempting to think that, as a professional, one knows what is best, but each individual’s values, traditions, and culture must be respected. This includes working to understand our own culture, what that looks like, and the impact it has on the people and the world around us. How do your intersectional identities impact those around you, and what weight do each of your identities carry in the world around you? Cultural responsiveness is something that evolves with you over your career as you understand more about yourself and the context around you.

Understanding intersectional identities will impact how you respond culturally. We are not experts in people’s lives and may not know every detail of our client’s lives, but we bring expertise and skills. With our unique identities, diverse experiences, and ongoing commitment to cultural responsiveness and humility, we provide a solid foundation for supporting our clients on their journey toward growth and healing. We must grow confident in our ability to positively impact our clients’ lives and help them achieve their goals.

Human services professionals must explore our cultural humility and identity work as a lifelong process. If we come from systems that have historically held more power, such as White cisgender men, it is especially important to challenge ourselves on the systems of power that we benefit from and reflect on our unconscious biases. Reflections about unconscious bias should happen in classrooms, during work meetings, while building treatment plans, in ethical decision-making, during the supervision of individuals and groups, and over our lifetime.

Depending on our intersecting identities, the depth and breadth of these experiences will look different. We need to center race, as this factor is central to the systems of power and privilege we have access to—not only as human services professionals but as humans. It is essential to ask ourselves questions such as, “When was the last time I had to prove my gender?” or “She does not look like she could be your mom; she looks Mexican, and you don’t.” “No, but where are you really from?” I am guessing many of you have not had to prove your mother was your mother by showing them a family picture off your wall just so police would believe you and let you and your mother walk into your apartment at the age of 7 years old just because she had a deep beautiful olive tone, eyes the color of toasted hazelnuts and dark jet black ringlet curls. You had peach-colored skin that Huitzilopochtli kissed from playing too long outside, untamed braids light brown with hints of red, and eyes the same shade of green from the grass you had just been playing in. Reflection is a critical practice that we must continue to grow as providers.

Where Theory and Practice Meet

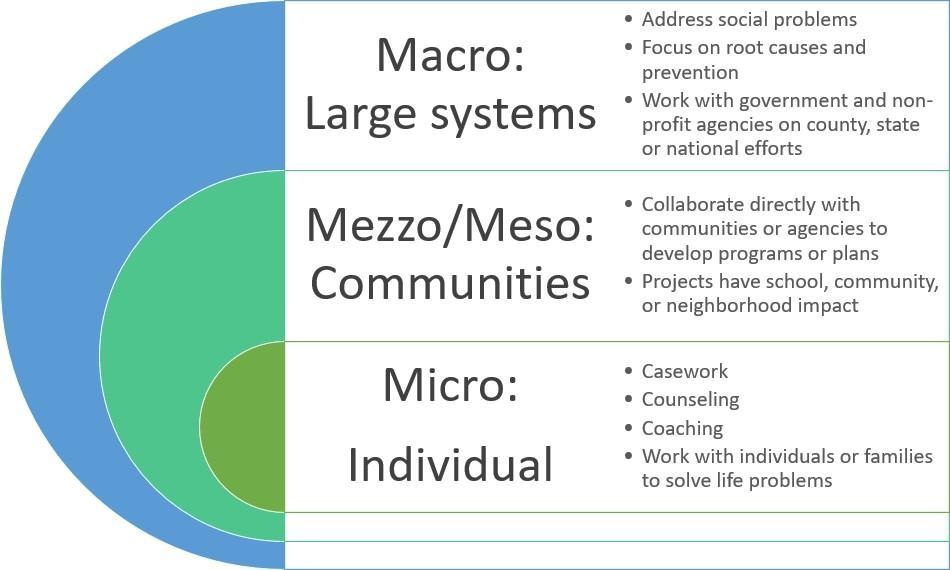

All of these approaches may be used in a variety of settings. Thinking about where you might apply these perspectives in your daily life can be helpful. Human services are often described as being applied at the macro, mezzo, or micro levels (figure 1.10).

Micro Level

Micro-level practice happens directly with an individual client or family. In most instances, this is considered to be a case management and therapy service. Micro-level work involves meeting with individuals, families, or small groups to help identify and manage emotional, social, financial, or mental challenges. This may include helping individuals find appropriate housing, health care, and social services. Micro-level practice may even include helping members of the military and families cope with military life and circumstances, helping with school-related resources, or working with clients around substance use, houselessness, or food insecurity.

The focus of micro-level practice is to help individuals, families, and small groups by providing one-on-one support and building skills to help manage challenges (Johnson & Yanca, 2010). Many professionals begin at the micro level to understand the inequalities, disadvantages, systemic oppression, and advocacy needed for vulnerable populations.

Mezzo (Meso) Level

Mezzo (meso) level practice involves developing and implementing plans with communities such as neighborhoods, places of worship, and schools. Professionals interact directly with people and agencies with the same passion, interest, location, or challenge. The big difference between micro- and mezzo-level social work is that instead of engaging in individual counseling and support, mezzo practitioners help groups of people. Human service professionals might help establish a free food pantry within a local place of worship, health clinics to provide services for the uninsured, or community budgeting and financial programs for low-income families.

While working at the mezzo level, professionals should be aware of the system oppression that affects individuals, families, and communities. For example, in a community that has high levels of contamination in its air and water, it may not be enough to advocate for additional healthcare resources. It may be equally valuable to advocate for the source of pollution to be clearly identified and pressured to make changes.

Macro Level

Macro-level practice is similar to mezzo practice in that both tend to address social problems. The macro practice is on a larger and less direct scale, and it often uses a preventative approach. The responsibilities on a macro level typically involve finding the root cause, the why, and the effects of citywide, state, and/or national social problems. Awareness of systems of privilege and oppression is foundational to this work.

Professionals are responsible for creating and implementing human service programs to address large-scale social problems. Macro-level social workers often advocate for state and federal governments to change policies to serve vulnerable populations better (Kirst-Ashman & Hull, 2015). They may be employed at nonprofit organizations, public defense law firms, government departments, and human rights organizations. While macro-level human services or social workers typically do not provide therapy or other assistance, such as case management, to clients, they may interact directly with the individuals while conducting interviews if they are researching the populations and social inequalities of their interest.

The human services and social work professions are broad and allow practitioners to move within the micro, mezzo, and macro levels. As you continue to read this text, consider the approaches described above as well as the level of human services work that is most appealing to you.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

“Theories and Practices Central to Human Services” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 1.8. “Strengths-Based Approach” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.9. “Cultural Responsiveness” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.10. “Micro, Mezzo, Macro Visualization” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.5. Photo of Aikia Fricke is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.6. “Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Model, Adapted to Focus On Black Youth Development and Attachment Processes in Context” by Jessica A. Stern, Oscar A. Barbarin, and Jude Cassidy is licensed under CC BY NC ND 4.0.

Figure 1.7. “Venn-diagram-ebp” by Carla M. Allen is licensed under CC BY ND 4.0.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

using multiple disciplines and methods.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

develop strategies that fend off problems

action taken to improve a situation or address a problem

the correction or reversing of actions or behaviors

conditions that might cause someone to become houseless or that are hazardous to the health of occupants of a home

focuses on the bi-diorectional impacts of an individual with different aspects of society

emphasizes the complexity of the environments that each individual interacts with.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

an approach based on scientific evidence, client values, and clinical experience.

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.

the practice of using the strengths of individuals, families, and communities to solve problems.

being aware that each individual you meet has their own set of beliefs, values, routines, and rituals that contribute to their culture.

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

(also known as “homeless”), when a person lacks a reliable place to sleep and care for themselves