2.2 Understanding the Historical Context of Human Services in the United States

To understand the history of human services and social work in the United States, it is important to place it in the context of the settlement and colonization of the states from the 1500s into the twentieth century. Many textbooks focus on the innovations of early White activists and social service providers without acknowledging the White supremacist practices that harmed Indigenous and Black individuals and families. Focusing on the accomplishments of White people and groups, and excluding BIPOC strengths and accomplishments, is known as “whitewashing.”

As the dominant racial-ethnic group, White European Americans enforced laws and practices that harmed Black and Indigenous families. At the same time, they maintained the power position of being the only ones to solve these family problems, which had been created through White dominance. Specifically, they used aggressive tactics to dislocate Native American communities and to remove children from their homes to be sent to boarding schools, all of which disrupted family ties. The intentional enslavement of Black people from Africa and the ways in which Black families were separated (married and partnered couples broken up, children removed from their biological families) caused great harm to family and community relationships. Once we acknowledge these actions, the responses of White activists can be seen in a different light. Perhaps they would not have been needed at all, or certainly not as much.

As you read this chapter, you may confront some uncomfortable or painful feelings. If you are a member of a group that was affected negatively by White dominant actions, it may be a relief to see those actions acknowledged as a contributing factor to the need for the human services and social work fields. Or it may add to pain and trauma that you and your ancestors have experienced. If you are a White person, it may be tempting to deny the past and its effects on the present. You may experience what is called “White fragility,” a concept that explains how and why White people are sensitive, uncomfortable, or defensive when confronting information about racial inequality, White dominance, and injustice (DiAngelo, 2018). You may be someone who relates to multiple ethnicities, racial identities, and conflicting feelings. With any feelings that you experience, you are not alone. Pay attention to your feelings and reflect on your responses, but keep reading.

This chapter will include White leaders who influenced the formalization of social services, and it will focus on the ways that Black, Indigenous, and people of color actually innovated and created caring practices and services that heavily influenced human services in the past and today. By examining cultural practices, this chapter attempts to resist and repair the damages caused by White supremacist ideology.

Why History Matters

History is used as a teaching tool to help shape the future. If what we learn from the historical record is not accurate, it will create a false narrative and reinforce harmful stereotypes.

Creating a more just future is embedded in the human services profession’s belief system, and an inaccurate view of the past distorts efforts to do so. Human services, like other academic disciplines, depends on history to train and equip students. It also readily uses history to inform theories, philosophies, and ideologies that shape the discipline and the next generations of human services professionals, social workers, mental health counselors, and other professions that help people solve life’s problems.

New students seeking to work in helping professions are learning a specific history that reinforces stereotypes: that BIPOC are the weak and inferior receivers of help, while Whites are the innovators and distributors of help and care. It is true that the majority of the people in helping professions such as social work are White (Council on Social Work Education, 2020). However, failing to tell the stories of leaders who were persons of color creates an inaccurate view of history and reinforces White supremacist ideologies. These BIPOC historical leaders largely remain unnamed and have been barred access to professional recognition for their contributions to social welfare.

Working to decolonize is an ongoing process that supports the decentering of Eurocentric ways of learning and understanding the world. The most essential part of decolonization is continual reflection. Education systems should be willing to reflect on curriculum, power dynamics, their structuring, and any action undertaken on behalf of their students. In addition, decolonization includes pointing out the strengths and accomplishments of marginalized communities that have been documented in the same ways that White accomplishments have been. It also requires giving credit to those BIPOC human service providers who have not received the recognition they deserve.

Failing to tell the full narratives around how people of color have helped themselves and led as helping professionals within their own communities is a disservice to a complete and honest understanding of social welfare history. This led to a historical pattern where Whites were often the “wounders,” after which a profession, like social work, was praised for creating a response that represented the “healers.” Consider how some White providers can slip into a White savior complex when they don’t examine the reason for supporting communities of color.

Remember that the White savior complex refers to an ideology that a White person acts from a position of superiority to rescue a BIPOC community or person. To truly understand the history of the profession, we must also acknowledge how White supremacy and racism affect Black, Indigenous, and people of color in family and community life. The White savior complex dynamic can be clearly seen in missionary work or “voluntouring,” which is a short trip that combines volunteer work with tourism. What is not considered when doing this type of work is how this will take paid work from locals in the area. Before taking such a tour, ask yourself: Could the money spent on the tour be donated to a local organization to benefit local infrastructure for longtime support rather than allowing an NGO to run all support systems in the region? Do I have the knowledge, skill set, and experience for the job at the level that this community needs for the work to be sustainable long-term?

All of these questions, as well as continued self-reflection and examination of privilege and power, can help us understand history and the need to decolorize the way we have learned it. These factors together influence how we function in human services as providers. Wanting to support communities in need is not wrong in itself; however, how did these communities get to this state? Am I the best person, or is my organization the best to do this work? How do privilege and power play a role in my decisions? These are not black-and-white choices; context always matters.

Origins of the Profession Intertwined with Racism

People have been providing social welfare to one another far longer than the profession has officially existed. Even social work, which has existed longer than human services and which shares similar foundations, has a debatable origin. It is often identified as having started in the mid- to late 1800s (Austin, 1983). During this time, the United States continued to enslave Black people and embraced the concept of manifest destiny, the belief that expansion of the United States throughout the West was determined by God. These efforts destroyed Native American communities and families. While there is some interpretation and analysis involved when discussing the origin of human services, the timing is deeply connected to a time when White supremacist racist actions were institutionalized.

Professional tradition has held that social welfare work sprang from frameworks and principles that spanned Europe, the United States, and the Middle East (Dulmus, 2012). It is difficult to date determine whether these principles or practices existed in other regions of the world, such as Asia, Central America, South America, or Africa. Although communal societies have long held the family or village responsible for the care of vulnerable persons, many Indigenous peoples passed down history orally and did not record their history in the same manner as Europeans did.

The Crowned White Founders of Social Welfare

Note: This section has an Activation Warning.

From the murder of Native peoples and the stealing of their land to legalized slavery and the Jim Crow era, BIPOC people have continued to be subjected to institutional racism for centuries while the White founders of the social work discipline were emerging. Jane Addams (1860–1935) has been described as a sociologist, philanthropist, labor reformist, advocate for juvenile justice, women’s suffrage proponent, and settlement activist (Harris, 2011). Addams is noted for having a long list of accolades that credit her with many accomplishments, including Yale University’s first honorary degree awarded to a woman and being the first woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize (Alonso, 2004). She is recognized in textbooks as one of the earliest influences on the creation of the juvenile justice system and as assisting in the earliest conceptualizations of the child welfare system. She has been crowned by the social work profession as the “mother of social work” (Joslin, 2004).

By current understanding, Addams was born into White privilege and benefitted from the concept of “the great White hope,” a slogan from the early 1900s expressing the idea that one race is superior to others. This phenomenon glorifies the White hero who “selflessly” comes to aid the ethnically different marginalized community (Pimpare, 2010). Such efforts are seen as sacrificial, as many White women like Addams fulfilled duties and responsibilities as wives and mothers, and did not work outside of the home (Brownlee, 1979). By serving the needy, Addams appeared to be “selflessly” deviating from her privileged position.

To recognize and challenge this whitewashing of the history of human services, the discipline must consider whether these criteria are still valid in determining who is deemed a founding member of social services and who is not. Addams was not alone in her quest for social welfare for the oppressed. Many BIPOC sacrificed so that future generations would experience social justices that they were denied during their own lifetimes. A host of Black activists, such as Edgar Daniel Nixon and A. Philip Randolph, who are both now recognized for their avid social activism, did jail time and suffered many hardships for advocacy work during the same period that Addams was gaining attention for her activism (Baldwin & Woodson, 1992; Kersten, 2007). Yet few BIPOC were awarded prizes. In the next section, we will discuss BIPOC social welfare communities and leaders whose efforts have been hidden or downplayed in the past.

Black Social Welfare Forerunners

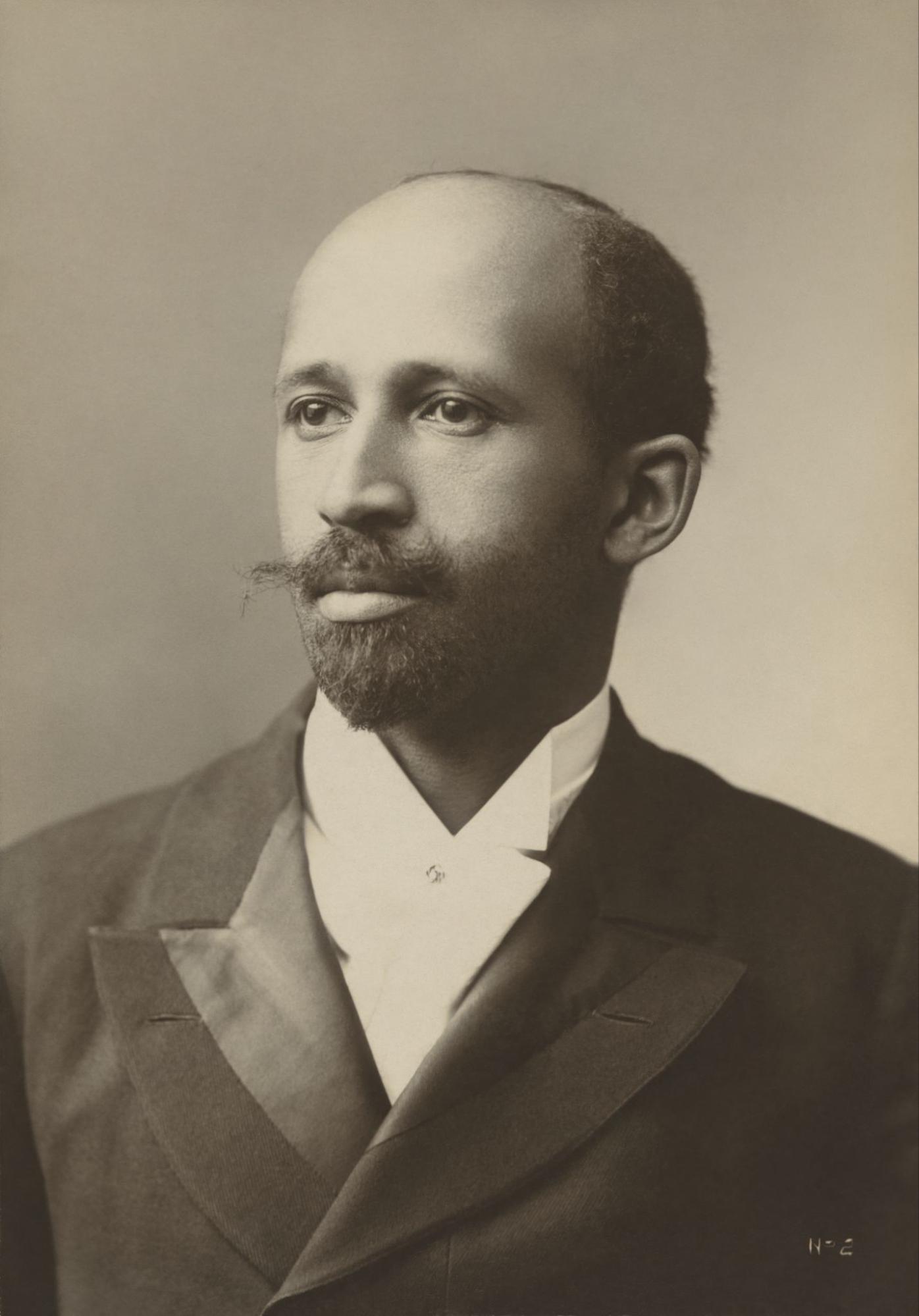

Three examples of Black early social welfare leaders are W. E. B. Du Bois, Eugene Kinckle Jones, and Ida B. Wells. Du Bois (1868–1963) lived during the same era as Addams. Du Bois, pictured in Figure 2.1, was the first African American to receive a doctorate from Harvard University (Morris, 2015). Interestingly, his work parallels that of the two founding women of social work. His work mirrored macro-focused social work. In fact, his research and work were so prolific that some scholars label him a sociologist (Green & Wortham, 2015).

One scholar suggests that Du Bois is the rightful yet forgotten heir to the title of “father of social work” (Morris, 2015). Du Bois fervently wrote to advocate for the advancement of people of color. He poignantly spoke and organized civil actions petitioning for structural change in institutions. Despite the overlap of Du Bois’s ideas and actions with social work, he is almost never mentioned as a founder of social work.

Du Bois, like Addams, did not have an opportunity to study social work because the discipline was not yet established as an academic or vocational category during their university careers. Yet his labor to study for the purpose of social activism and reform seems equal to Addams’s efforts. Du Bois fought for social justice amid Jim Crow laws, legal lynching practices (Morris, 2015), and legally supported institutional racism. Due to widely held racist views and structures, Du Bois did not receive a Nobel Peace Prize for his work at the time, just as many BIPOC activists have not received credit for their accomplishments over the years due to these structures.

A second example of a Black social work pioneer is Eugene Kinckle Jones (1885–1954), a leader in the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes, now renamed the National Urban League (NUL). This organization has historically advocated against racial discrimination (Fenderson, 2010). Jones is well known for his focus on advocating for better health, housing, and economic conditions. He worked for the inclusion of Black employees in labor unions, organized civil rights activism against businesses that were legally able to deny jobs to Black people, and advocated for school reform to incorporate more opportunities for people of color. Jones was elected to the leadership of the National Conference of Social Work (NCSW) in 1925, and he was the first Black person on the executive board of the NCSW (Armfield, 2011; Armfield & Carlton-LaNey, 2001).

A third example of a Black social welfare leader is Ida B. Wells (1862–1931), who set the foundation for the modern-day civil rights movement. Much of her activism occurred via her work as a journalist and speaker. She was well known for her anti-lynching activism, including building awareness internationally, as she worked for social justice. She advocated for African-American equality, especially that of women (Dickerson, 2018). She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1909 with W. E. B. Du Bois and others.

Modern-Day BIPOC Leaders and Scholars

Some scholars are seeking to uncover the work of people of color’s contributions to social welfare. One scholar, Dr. Crystal Coles, uses older documents to examine common activities and characteristics of people from the southern region of the United States (Coles et al., 2018). She highlights the unique role of research inquiry in exploring marginalized peoples’ influences on social work. She studies primarily the impact African American women have had on social work in specified regions of the South. Finding many Black women in roles that we now would call “community educators” and “civil rights advocates” with Dr. Hohl did more extensive research on 121 women.

Similar methods are used to examine the revolutionary lives of 121 Black women who led in many social welfare-involved vocational roles, though they were legally barred from doing so because of the color of their skin. Another scholar, Dr. Elizabeth Anne Hohl, posthumously assigned, for these women, social roles and vocational titles that many were denied legal rights to claim because of their ethnicity and/or gender identity. These women, each of them born in the 1800s, were deemed to have embodied roles such as: “community educators,” “civil rights advocates,” “abolitionists,” “community leaders,” or “philanthropists” (Hohl, 2010). When looking deeper into the lives of these individuals and the types of activities in which they engaged, many of them could be called a social worker, human services worker, or social welfare advocate.

One notable challenge with finding and naming solitary leaders among BIPOC is that many BIPOC communities valued and practiced co-sharing of roles. Focusing on an individual’s influence is more of a White culture characteristic; the celebration of Addams’s work is one example (Okun & Jones, 2000). An example of the more collective BIPOC approach is found in the work of Coles and her colleagues. They reference the work of a hundred-year collaboration of women of color to create and sustain a health system in Virginia. These women, who were operating in the majority culture’s societal opposition and legal barriers, were able to create a social welfare structure within the health sector that continued to endure for centuries.

Another example of a modern-day BIPOC scholar is Hilary Weaver, member of the Lakota Nation, whose work on Indigenous peoples uncovers many untold stories of advocacy and social welfare efforts. In one piece of her work, Weaver (2020) described the four-decade story of two Indigenous women, the Conley sisters, who led a successful collective struggle to protect a Wyandotte Nation burial ground in Kansas City. In this same chapter, Weaver described Laura Cornelius Kellogg, an Oneida activist who founded the Society of American Indians and fought for economic self-determination, education, and land recovery at great personal cost. The retelling of these stories of Indigenous advocacy and leadership further demonstrates how White filtering of history has omitted many BIPOC contributions to social welfare-involved work.

Licenses and Attributions

“Understanding the Historical Context of Human Services in the United States ” is adapted from “The Whitewashing of Social Work History: How Dismantling Racism in Social Work Education Begins With an Equitable History of the Profession” by Kelechi C. Wright, Kortney Angela Carr, and Becci A. Akin in Advances in Social Work, Vol. 21 No. 2/3 (2021): Summer 2021-Dismantling Racism in Social Work Education is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: Edited for brevity; slight reorganization of content; contextualized for human services; revised reading level.

Figure 2.1. “W. E. B. DuBois.” by James E. Purdy, 1907, gelatin silver print, from the National Portrait Gallery is licensed under Creative Commons–Public Domain License.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

focusing on the accomplishments of White people and groups,and excluding BIPOC strengths and accomplishments

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

well-being

the acts of identifying systems of oppressive colonization, dismantling historical records that emphasize the dominant culture’s story, and striving to effect power structures so that they are shared more equitably.

refers to the geographical location that a person was born and spent (at least) their early years in

an academic rank conferred by a college or university after completion of a specific course of study.

typically refers to any situation where the child’s needs are paramount and their immediate protection takes priority over the other family needs

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

viewpoints and efforts toward every person receiving and obtaining equal economic and social opportunities; removal of systemic barriers.

social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

the act of working with others.