3.2 Trauma: A Common Experience

Trauma impacts people of all ages and all walks of life. More than 60 percent of adults have experienced at least one traumatic event, and about 25 percent reported experiencing three or more traumatic events before the age of eighteen (Merrick et al., 2018). Working in the human services profession, you are likely to encounter many clients who have been traumatized. As a result, it’s crucial to understand what trauma is and how you may directly or indirectly address it in your career.

At the same time, you are likely to hear many stories of trauma when working with clients, which can be a traumatic experience in and of itself. This is another reason that it is essential for human service workers to understand trauma and have knowledge of wellness practices to address it.

Defining Trauma

Since the 1990s, a number of different definitions of trauma have been developed by professionals and researchers. Desiring a unified concept, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) drew on these existing definitions to establish a framework for understanding trauma.

According to SAMHSA (2014), trauma is the result of an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. Generally, there are four kinds of trauma: acute trauma, chronic trauma, complex trauma, and intergenerational trauma, as shown in figure 3.1.

Note: This table has an Activation Warning.

| Kind of Trauma | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | A single traumatic incident | A car accident or a natural disaster. It may only be a single incident, but it can have lasting effects, such as fear of being in a vehicle. |

| Chronic | A traumatic experience repeated over a period of time | Intimate partner violence, family violence and war. Both have lasting effects on many people, and the consequences can be hard to overcome. |

| Complex | A repeated traumatic experience inflicted by a caregiver | Physical abuse, sexual /violence abuse, and verbal/emotional abuse (also known as psychological abuse). Complex trauma leaves a child confused and conflicted. The person who inflicted harm was supposed to be the one protecting them and keeping them safe. When that does not happen, the child does not know who to trust. |

| Intergenerational | Descendants of a traumatized person react as if the trauma was experienced by them (American Psychological Association [APA], 2022) | Many groups have experienced intergenerational trauma, including descendants of Guatemalan genocide survivors, Rwandan genocide survivors, Native American boarding school survivors, and enslaved persons. Parents and grandparents pass down trauma responses in the way they model and teach relationship skills, behaviors, values, and beliefs. |

| Systemic | Beliefs, practices, and cultural norms that reinforce the oppression of marginalized communities | Racism, ableism, homophobia, xenophobia, White supremacy, transphobia, and misogyny are some examples. |

Events, Experiences, and Effects of Trauma

SAMHSA also developed the concept of the three E’s of trauma: event(s), experience of event(s), and effect. These three Es further define the concept of trauma and its effects on individuals.

Events or circumstances include the actual fear of reaching out for help, the extreme threat of physical or psychological harm (i.e., natural disasters, violence, etc.), or severe neglect of a child that imperils a healthy range of factors, including the individual’s cultural development (SAMHSA, 2014). These events may occur once or may be repeated over time.

The individual’s experience of these events helps determine whether it is traumatic (SAMHSA, 2014b). Something traumatic for one individual may not be traumatic for another individual. For example, two soldiers may serve in a combat zone, but only one may develop post-traumatic stress disorder. Similarly, siblings may respond differently to the incarceration of a parent.

How an individual experiences the event may be linked to various factors. These factors include the individual’s cultural beliefs, such as the subjugation of women and the experience of intimate partner violence. Another factor is the availability of social support, whether the individual is isolated or embedded in a supportive family or community structure. Finally, they also include the developmental stage of the individual. For instance, an individual may understand and experience events differently at age five, fifteen, or fifty (SAMHSA, 2014b).

The long-lasting adverse effects of the event are a critical component of trauma. These adverse effects may occur immediately or may have a delayed onset. Examples of adverse effects include an individual’s inability

- to cope with everyday stresses,

- to trust and benefit from relationships,

- to manage cognitive processes, such as memory and attention,

- to regulate behavior,

- or to control the expression of emotions.

In addition to these more visible effects, there may be an altering of one’s neurobiological makeup and ongoing health and well-being (SAMHSA, 2014b).

Traumatic effects may range from hypervigilance, or a constant state of arousal, to numbing or avoidance. These effects can eventually wear a person down physically, mentally, and emotionally. Trauma survivors have also highlighted the impact of these events on spiritual beliefs and the capacity to make meaning of these experiences (SAMHSA, 2014b). In the next section, we’ll discuss the science behind how trauma impacts physiological and psychological processes.

Recent research and the development of new theories have helped us better understand how trauma affects individuals in the long term. These theories give us an idea about how early trauma disrupts neurodevelopment and psychological processes. At the same time, by better understanding trauma, we can work to develop better interventions to address its impact.

Attachment Theory

Children who experience trauma may develop issues with attachment. Attachment theory, pioneered by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth, highlights how attachment patterns originate from the earliest stages of life. Bowlby’s work focused on the bond between the infant and the primary caregiver. He developed a model of four stages of early development attachment that children go through from birth to two years old. He believed this was a critical part of development and that attachment experiences have long-lasting impacts on children. Particularly, these early attachment experiences shape future relationship patterns.

Ainsworth expanded upon this work to develop a typology of four kinds of attachments that children have with their mothers (primary caregivers). In her research, she looked at how children between the ages of one and two responded to mothers leaving and returning. Her research describes the following attachment types shown in figure 3.2.

| Attachment Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Secure | Children are distressed when their caregivers leave and quickly become calm when their caregivers return. |

| Anxious – Avoidant | Children do not seem to care when their caregivers leave, despite internal distress, and do not react when their mothers return. |

| Anxious – Ambivalent | Children are in distress when their caregivers leave and feel ambivalent when their caregivers return, alternating between being clingy and avoidant. |

| Disoriented – Disorganized | Children lack any consistent pattern in response to separation and return of the caregivers. |

Like Bowlby, she claimed that these attachment styles impacted future relationships outside of the family. Because of this, developing a secure attachment is integral to children’s emotional, cognitive, and interpersonal development. There is some research to support these claims. Research suggests that children are more likely to develop secure attachments if parents consistently meet their needs (Lahousen et al., 2019).

So, how do these ideas about attachment relate to trauma? Early traumatic experiences can influence the extent to which children feel safe and can form secure attachments. Traumatic experiences are associated with insecure attachment styles and have a neurobiological impact on individuals, particularly during the early stages of development (Lahousen et al., 2019). Trauma impacts various brain regions, some of which encode traumatic information that may later lead to emotional or behavioral problems (Lahousen et al., 2019). These regions are involved in development, leading to behavioral problems and stress reactions later on (Lahousen et al., 2019). These issues often reflect an insecure attachment style.

Trauma-Informed Care

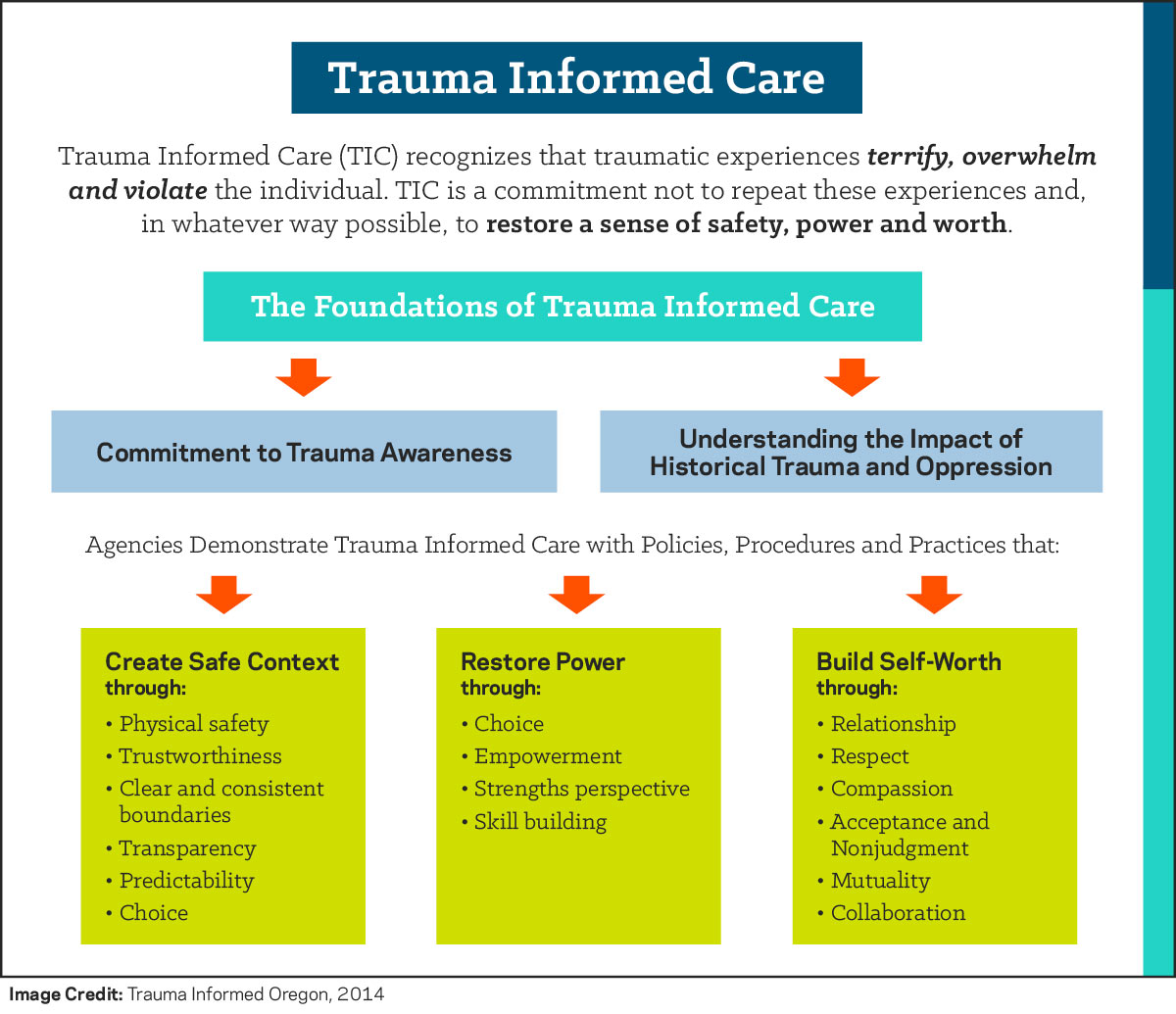

In treatment settings, there is a helpful distinction between treating the trauma experience and treating the symptoms of trauma (Atkins, 2014; Dass-Brailsford, 2007; Friedman et al., 2014). Although there are numerous evidence-based treatment approaches for treating the experience of trauma, not all providers are trained and qualified to treat trauma. Trauma treatment requires specialized training and supervised experience (Dartmouth Psychiatric Research Center, 2015; SAMHSA, 2014a). This has the potential to create a treatment gap between the number of trained providers in trauma care and the treatment needs of patients with trauma histories. Even though not every provider is trained to engage in trauma processing therapies, it is recommended that institutions train their professional staff in the ability to provide care that is sensitive to the unique symptoms of trauma (SAMHSA, 2014b). A structured approach that institutions can use to provide such care is known as trauma-informed care (SAMHSA, 2014a; Curran, 2013).

Trauma-informed care is a collection of approaches that translate the science of the neurological and cognitive understanding of how the brain processes trauma into informed clinical practice for providing services that address trauma symptoms (SAMHSA, 2014a; Curran, 2013). It is important to note that trauma-informed care is distinct from trauma-specific practices.

Trauma-specific practices directly treat the trauma an individual has experienced and any co-occurring disorders that they developed due to this trauma. Trauma-specific practices include interventions such as prolonged exposure therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), and trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (Menschner & Maul, 2016). Practitioners must undergo special training to utilize these techniques, so not every organization may offer these treatments.

A trauma-informed care approach can include trauma-specific practices and incorporate key trauma principles into the organizational culture. This approach is not designed to treat the trauma experience (such as processing the trauma narrative), but rather to assist in managing symptoms and reducing the likelihood of retraumatization of the patient in the care experience (Najavits, 2002; SAMHSA 2014b). As such, interventions of trauma-informed care are appropriate for a range of practitioners to utilize in various clinical settings.

Assumptions of Trauma-Informed Care

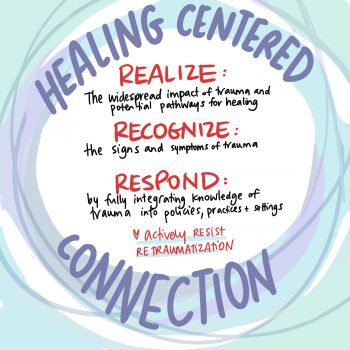

Along with defining the concept of trauma, SAMHSA’s approach to trauma-informed care includes four assumptions and six key principles. There are four R’s that highlight the key assumptions of the trauma-informed care framework: realization, recognition, response, and resistance to retraumatization.

A program, organization, or system that is trauma-informed

- realizes the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery,

- recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system,

- and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist retraumatization (SAMHSA, 2014b).

By realizing trauma, people’s experiences and behavior are understood in the context of coping strategies designed to survive adversity and overwhelming circumstances. Their experiences and behavior may be related to past circumstances, such as a client dealing with prior child abuse. They may currently be experiencing trauma, such as a client experiencing intimate partner violence. Finally, clients’ experiences and behavior can be related to the emotional distress that results from hearing about the firsthand experiences of another, such as the vicarious trauma experienced by a human services professional.

There is an understanding that trauma plays a role in mental and substance use disorders. Prevention, treatment, and recovery settings should systematically address trauma (SAMHSA, 2014b). Trauma is not only present in the behavioral health sector. It also plays a significant role in education, child welfare, criminal justice, health care, and other community organizations addressing social problems. Trauma is as much of a barrier to effective outcomes in these systems as it is in mental health and substance use disorder treatment.

When engaged in trauma-informed care, people in the organization or system can also recognize the signs of trauma, including how these may present differently in various settings or populations (SAMHSA, 2014b). People in the organization use screening and assessment tools to help identify trauma. Additionally, organizations should provide training for staff members so that they can identify trauma responses.

The program, organization, or system responds by applying the principles of a trauma-informed approach to all areas of functioning. The program, organization, or system integrates an understanding that the experience of traumatic events impacts all people involved, whether directly or indirectly (SAMHSA, 2014b). Staff in every part of the organization change their language, behaviors, and policies to consider the experiences of trauma among children and adult users of the services and staff providing the services.

Organizations accomplish these changes through staff training, a budget that supports this ongoing training, and leadership that realizes the role of trauma in the lives of their staff and the people they serve. The organization has practitioners trained in evidence-based trauma practices. The organization’s policies—such as mission statements, staff handbooks, and manuals—promote a culture based on beliefs about resilience, recovery, and healing from trauma. The organization is committed to providing a physically and psychologically safe environment. Leadership ensures that staff work in an environment that promotes trust, fairness, and transparency. The program’s, organization’s, or system’s response involves a universal-precautions approach in which one expects the presence of trauma in the lives of individuals being served, thereby ensuring not to replicate it (SAMHSA, 2014b).

A trauma-informed approach seeks to resist the retraumatization of clients and staff (SAMHSA, 2014b). In a trauma-informed environment, staff recognize practices that strip clients of agency or make them feel trapped—both of which they may find retraumatizing. At the same time, trauma-informed organizations ensure they are not retraumatizing staff by creating a high-stress environment without proper support.

Key Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

In addition to these four assumptions, there are six key principles of a trauma-informed approach: safety; trustworthiness and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment, voice, and choice; and cultural, historical, and gender issues.

- Safety refers to staff and clients throughout the organization feeling secure physically and psychologically. The physical setting and interpersonal interactions at the organization should promote safety. Staff at the organization should not assume what their clients need to feel safe but rather provide opportunities for clients to express what safety means to them.

- Trustworthiness and transparency are directly related to one another. When organizational decisions are made with transparency, they build and maintain a sense of trust with clients, staff, and others involved with the organization.

- Peer support is another principle that helps build trust, enhance collaboration, and establish safety and hope. By having support from others who have experienced trauma, survivors can begin to see the possibilities of recovery and healing.

- Collaboration and mutuality refer to narrowing power differentials between clients and staff, as well as among staff. Collaboration helps demonstrate that healing happens within relationships and in the meaningful sharing of power and decision-making. By having all parties at the table when decisions are being made, the organization recognizes that everyone has a role to play in creating a trauma-informed organization.

- Empowerment, voice, and choice refer to recognizing and building upon individuals’ skills and strengths. Trauma-informed care is a strengths-based approach where the organization and its staff foster a sense of resiliency among the people they serve. They believe in the ability of people and communities to heal from trauma and recognize how they are experts in their own experiences. Staff understand how important it is for clients to be empowered and to have a voice and choice in their treatment. Clients are supported in shared decision-making, choice, and goal-setting to determine the plan of action they need to heal and move forward (SAMHSA, 2014b). Staff are also empowered to do their work.

- Cultural, historical, and gender issues are the final principle of trauma-informed care. Trauma-informed organizations are aware of cultural biases, stereotypes, and systemic inequalities. In their work, they recognize the role of historical trauma and the importance of addressing that as part of the healing process. In conjunction with this, they have policies, procedures, and culturally responsive protocols that draw on the unique needs of the population they serve and leverage cultural connections to improve care.

These principles can be applied in many contexts, even though specific practices or terminology vary between settings. Developing a trauma-informed approach requires change at multiple levels of an organization to reflect these principles. Figure 3.4 combines all of the pieces of the trauma-informed care approach we’ve discussed.

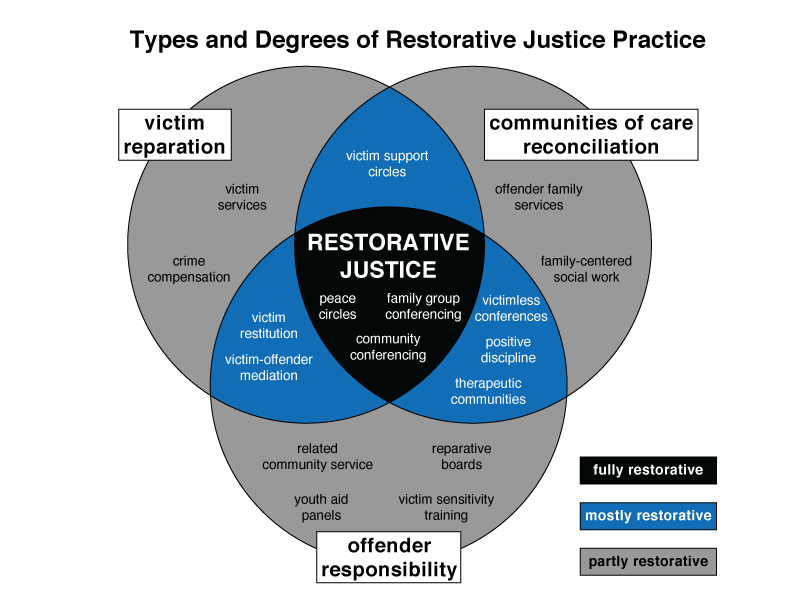

Restorative Justice vs. Restorative Practice

To begin to understand Restorative Justice and Restorative Practice, we must first understand the origins of the practice. These origins are at the center of how restorative justice differs from the type of justice and repair systems currently practiced in the United States.

Restorative Justice, often misunderstood, is not a new concept in the criminal justice system. It’s a well-established approach that is gaining recognition for its effectiveness. These vital practices have been braided into every aspect of Indigenous communities for generations. However, they have been colonized by the United States in ways that do not truly recognize how intense this practice is. It has best been described by Dr. Fania Davis and Dr. Howard Zehr in their work over the last several decades.

Restorative Justice is a theory or framework of justice that focuses on mediation and agreement rather than punishment. Participants must accept responsibility for harm and make restitution to those they have harmed. Indigenous people like the Maori have used this system successfully in their communities for generations. The well-known component is this community circle. The video linked below describes the history of Restorative Justice and its practices, philosophies, and values. This is an overview of Restorative Justice by Amplify RJ [Streaming Video]. Although it is a bit long at 30 minutes, it is a deeply informative and approachable introduction to deeper concepts.

Restorative Justice is another method of achieving justice with Indigenous roots, both African and Native American. It views crime as a harmful act against the community as a whole rather than as a harmful act against the system or state. Numerous Indigenous communities practiced restorative justice for years until it was disrupted by colonization and the arrival of Eurocentric values.

Chapter Two of Davis’s The Little Book of Race and Restorative Justice goes into great detail about the indigenous tribes in Africa and Native Americans in Canada who used restorative justice, which I highly encourage. Davis quotes an author who wrote a book about Indigenous teachings and the roots of restorative justice, Kay Pranis, to explain that restorative justice has a much deeper meaning and significance that non-indigenous people cannot see at the surface level (Davis 2019).

Without an understanding of how vital interrelatedness is to Indigenous communities, we will never understand restorative justice in its entirety. Davis also assures the reader that we can avoid cultural appropriation if restorative justice is appropriately performed. It is essential to recognize the Indigenous roots of the practice and name them in your space practice before utilizing restorative justice as community healing.

Restorative practices are often confused with restorative justice work. They are different, though they coexist in the same spaces in many instances. Some restorative practices that are most familiar to the public include restorative circles or talking circles, for example, as described by The Center for the Study of Social Policy:

Talking circles is another approach rooted in restorative practices, which embodies hozhooji naat’aanii, a Navajo phrase meaning “something more like ‘people talking together to re-form relationships with each other and the universe.'” Youth circles underscore youth’s interconnectedness with and responsibility for their community. In a paper exploring the use of restorative justice in residential placements in Northern Ireland, psychologist and advocate William McCarney observes that talking circles in residential care centers can help youth “develop prosocial skills and attitudes” and “a sense of community and civic spirit, empathy, and … a sense of belonging and connectedness.” E Makua Ana Youth Circles in Hawai’i, which supports youth transitioning out of foster care, emphasizes the ability of youth to use their participation in the circle to not only recognize their strengths but also those of one’s family, community, and social service workers as supports in their transition period (Marsh, 2019).

Many people in the United States were first introduced to restorative circles by the criminal legal system and have only connected it to this system. However, when these circles are used in these systems, which are not and cannot be restorative, their depth is superficial. The people who have been trained in running the circles have not done the necessary practices to do true restorative work, and the system as it is constructed cannot support long-term change.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

All other content in this section is original content by Alexandra Olsen and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Addressing Specific Traumas” by Alexandra Olsen is a remix of “Chapter 9 Safety and Stability” by Alexandra Olsen in Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2nd edition, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Trauma-Informed Care” by Alexandra Olsen is adapted from/a remix of“Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I -Trauma Informed Care” by Jennifer A. Burns, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0. Citations have been edited for style.

“Trauma: A Common Experience” by Alexandra Olsen is a remix of “Chapter 7: Child Welfare and Foster Care” by Eden Airbets in Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University, “Chapter 9: Social Work and the Healthcare System” by Kaitlin Ann Hetzel in Introduction to Social Work at Ferris State University, “Chapter 9 Safety and Stability” by Alexandra Olsen in Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 2nd edition, “Fast Facts: Preventing Intimate Partner Violence” by the CDC, and “Chapter 4: Violence Against Women” by Bureau of International Information Programs, United States Department of State in Global Women’s Issues: Women in the World Today, extended version licensed under CC BY 4.0. Substantial modifications and edits have been made.

Figure 3.1 is adapted from a table created by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Alexandra Olsen for “Introduction to Human Services 2e,” licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.2 is adapted from a table created by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Alexandra Olsen for “Introduction to Human Services 2e,” licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.3. “Healing-centered connection” by Drawing Change is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.4 is adapted from “Dynamics of Interpersonal Relations I -Trauma Informed Care” by Jennifer A. Burns, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0. Citations have been edited for style.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 3.5. “Restorative Justice” by an unknown artist is licensed under fair use.

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

a single traumatic incident

a traumatic experience that is repeated over a period of time

a repeated traumatic experience that has been inflicted by a caregiver

a phenomenon in which the descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself

the failure to meet the basic needs of a child

any incident or pattern of behaviors (physical, psychological, sexual or verbal) used by one partner to maintain power and control over the relationship

a theory that highlights how attachment patterns are developed from the earliest stages of life

a collection of approaches that translate the science of the neurological and cognitive understanding of how trauma is processed in the brain into informed clinical practice for providing services that address the symptoms of trauma

practices that directly treat the trauma that an individual has experienced and any co-occurring disorders that they developed as a result of this trauma

system of shared assumptions, values, and beliefs that show people what is appropriate and inappropriate behavior in a particular agency or workplace.

the intentional emotional, negligent, physical, or sexual mistreatment of a child by an adult

secondary traumatic stress, which is an occupational challenge for people working in the human services field due to their continuous exposure to victims of trauma and violence.

develop strategies that fend off problems

well-being

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

the act of working with others.

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

the practice of using the strengths of individuals, families, and communities to solve problems.

an alternative approach to criminal justice that centers the survivor, taking into account what they need to experience healing. It also involves the participation of the perpetrator, requiring them to recognize the harm they did in the process of holding them accountable.

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

strategies that build, strengthen, and repair relationships among individuals, as well as connections within communities.

being able to feel and relate to another’s feelings.

a temporary placement of a child with another family while parents are resolving issues