5.5 Social Insurance Programs

Social insurance programs differ from social welfare programs in that they take into account any contributions that the beneficiary has made to the program. These programs may be considered more preventative in nature than social welfare programs.

Social Security Disability Insurance

Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) covers individuals who have worked enough years to qualify for Social Security payments if they become disabled with a condition that “is expected to last at least one year or result in death” (Social Security Administration, 2014, p. 4). Since this is not a public assistance program, applicants do not need to pass a means test. Benefits can also extend to some family members. After receiving SSDI benefits for two years, the recipient automatically becomes eligible for Medicaid benefits as well. (Social Security Administration, 2014).

Medicare

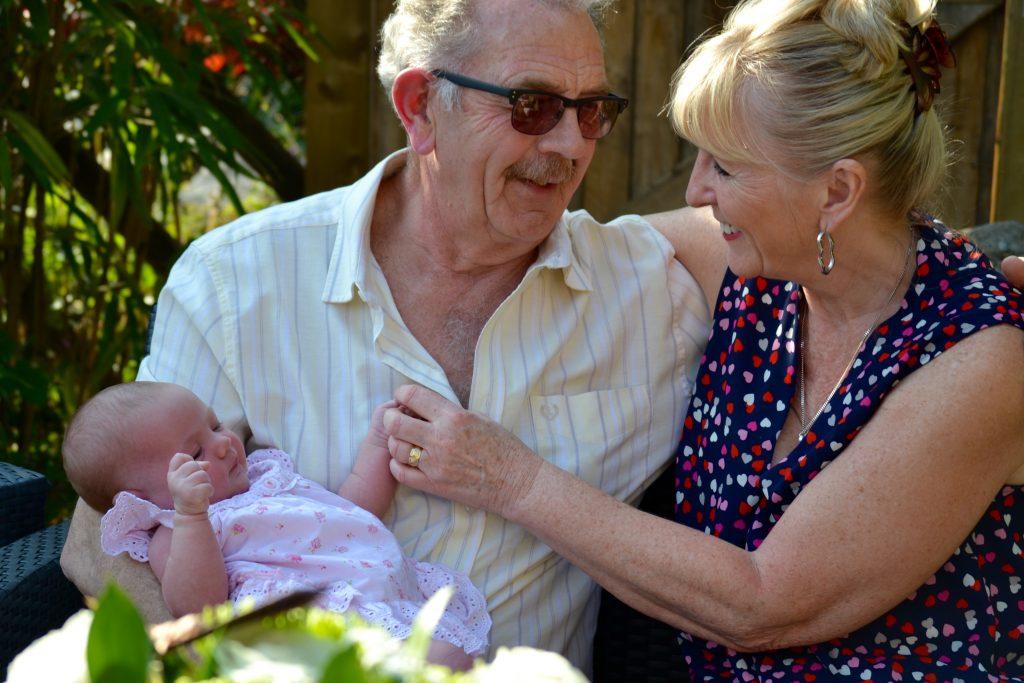

Medicare is a program funded by tax revenues that provides financial assistance for medical care for the nation’s elderly, retired, and some people with disabilities, as shown in figure 5.7. Much more complex than Medicaid, Medicare’s benefits come in various forms (Part A, Part B, Part C, Part D). Part A (inpatient hospital coverage) is free, with the remaining optional components requiring the payment of a premium. Medicare is addressed in greater depth in Chapter 8.

Social Security

Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) is the formal name for the program we more typically call Social Security. It provides an income to “qualified retired and disabled workers and their dependents and to survivors of insured workers” (Social Security Administration, 2011). Over 50 million Americans receive benefits, including more than 85% of those aged 65 or older (Social Security Administration, 2011). Although it was never designed to be the primary source of income for the elderly, it is at least 90% of the income for 22% of married couples, and 43% of the income for other individuals aged 65 or older (Social Security Administration, 2011).

There is some concern about the long-term viability of Social Security due to the increasing average age and life expectancy of Americans, coupled with the trend of companies encouraging older workers to go into early retirement (Baker & Weisbrot, 1999). Some people will see little return on their Social Security tax payments, while others will draw much more out of the system than they put into it. The maximum monthly benefit payable to a retired worker in 2021 was $3,148, but they could only collect that much if they had earned $142,800 or more each year over a 35-year working career. The average retiree’s monthly Social Security payment in 2021 was $1,543 per month (Brandon, 2021). Social Security will be discussed more in depth in Chapter 7.

Unemployment Insurance

Unemployment insurance (UI) is aimed at preventing recently unemployed workers from slipping into economic despair while they search for a new job. There is no means test, and benefits paid out are based on earnings from one’s previous job. The program is funded by a tax paid by employers rather than employees (Conrad, 2008). Workers can generally apply only if they’ve been laid off, but in some cases people who have been fired are eligible (Kirst-Ashman, 2013). In order to continue to receive benefits, one must also be actively looking for work and be able to furnish proof of that fact (Stone & Chen, 2014).

Each state runs its UI program quite differently. Payment levels are determined by how much the worker earned while working and what the average income is in that state, and benefits are often capped at around half the worker’s previous earnings (Levitan et al., 1998). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government also provided additional payments beyond state unemployment payouts, adding $300 per week for many people in need (Guerin, 2021).

Workers’ Compensation

Like UI, worker’s compensation insurance is meant to help people stay out of poverty during temporary loss of income—in this case, due to an injury or disease incurred on the job. Workers’ compensation is designed to cover lost wages, medical treatment for the condition, and possible rehabilitation, and to compensate one’s family in the event of a workplace-related death (Levitan et al., 1998; Matthews, 2015). However, the total of an individual’s disability benefit payment (if any) and worker’s compensation payment cannot exceed more than 80% of their working income (Matthews, 2015).

Activity: Is the U.S. Really a Meritocracy?

Earlier in the chapter, we asked if most of the hardworking people in the United States could be concentrated in the top 10%, or the top 1%? A meritocracy, which many believe the United States to be, would make this possible. Imagine the following scenario, which illustrates vividly the relative lack of connection between hard work and economic success.

An educated white man, Mark, was laid off after over three decades working as a mechanical engineer. He was in his mid-fifties at the time, making over $100,000 a year, and had started working on his master’s degree in business administration (MBA). He continued to go to school after being laid off and finished that degree, all while struggling to find new work in his field.

With multiple patents to his name, managerial experience, and decades’ worth of knowledge—plus now an advanced degree—one would think that it would be easy for him to find another job. He did find a new job assembling bicycles at a bike shop for a few months, but he left because of the shop owner’s racist views. Then, he was a shelf stocker in a grocery store’s liquor section. Then, he took a job as a school bus driver. Over those years, he put out dozens, perhaps hundreds, of resumés and scored many interviews, but never an offer that would put him back into engineering or management.

Why couldn’t he find a well-paying job? Why did he often have to settle for low-wage manual labor? A lot of factors led to his predicament. His decades of experience and his advanced degree had in some ways made him more difficult to hire because he legitimately would have commanded a high salary. When he applied for jobs that paid less but for which he was overqualified, he would not get offers, perhaps because the employers were afraid he’d leave once he got something better. Some people in the industry even recommended he take his MBA off his resumé so human resources managers didn’t see him as too expensive to hire.

Mark was a lot more fortunate than most, since he had a well-paying career before his years of unemployment and underemployment. However, if the system favored those who got educated and worked hard, he would have had a lot more success in his job hunt. He has since become disabled, and now at age sixty-four he would have almost no chance of getting a job in his field since people would just see him as a soon-to-be retiree. It’s likely that many readers know people with similar stories.

Reflection questions:

- What public safety net programs would you recommend restructuring and why? How?

- Can you think of other examples that demonstrate whether or not the United States is a meritocracy?

There are many factors that people cannot control that cause them to be unemployed, to file for bankruptcy, or to apply for public safety net programs. It is our job as social workers to know that what our clients really need is not judgment. They need someone to recognize that they are people who have a story and deserve an opportunity to get on their feet, regroup, and keep fighting against a powerfully unequal system.

Conclusion: Progress and Change

Social problems are persistent. They have continued for decades and even centuries, and some appear to worsen over time. In view of social problems’ long history, certainty of continuing for some time to come, and serious consequences, it is easy to feel overwhelmed when reading about them, to think that little can be done about them, and even to become a bit depressed. As a result, it is easy for us to come away from a chapter about social problems and poverty with a rather pessimistic, “doom and gloom” outlook.

But there can be progress, and conditions change. Although social problems are indeed persistent, some problems are less serious now than in the past. Change is possible. As just one of many examples, consider the conditions that workers face in the United States. Many people today are unemployed, have low wages, or work in substandard and even dangerous workplaces. Yet they are immeasurably better off than a century ago, thanks to the US labor movement that began during the 1870s. Workers now have the eight-hour day, the minimum wage (even if many people think it is too low), the right to strike, and workplaces that are much safer than when the labor movement began. In two more examples, people of color and women have made advances since the 1960s, even as they continue to experience racial and gender inequality. To repeat: Change is possible.

How does change occur? One source of change in social problems is social science theory and research. Over the decades, theory and research in sociology and the other social sciences have pointed to the reasons for social problems, to potentially successful ways of addressing them, and to actual policies that have succeeded in addressing some aspect of a social problem. The findings from sociological and other social science research have either contributed to public policy related to this chapter’s social problem or have the potential of doing so. Frequently, human services professionals are involved in making changes at the macro level or implementing those changes on a mezzo or micro level, alongside communities and individuals.

The actions of individuals and groups may also make a difference. Many people have public-service jobs or volunteer in all sorts of activities involving a social problem. They assist at a food pantry, they help clean up a riverbank, and so forth. Others take on a more activist orientation by becoming involved in small social change groups or a larger social movement. Our nation is a better place today because of the labor movement, the Southern civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the gay rights movement, the environmental movement, and many others. Ordinary people can change America (Piven, 2006).

Sharing this view, anthropologist Margaret Mead once said, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” Change is not easy, but it can and does occur. In this optimistic spirit we see examples in this book of people making a difference in their jobs, volunteer activities, and involvement in social change efforts.

Change also occurs in social problems because policymakers (elected or appointed officials and other individuals) pass laws or enact policies that successfully address a social problem. They often do so only because of the pressure of a social movement, as pictured in figure 5.8, but sometimes they have the vision to act without such pressure. It is also true that many officials fail to take action despite the pressure of a social movement, so those who do take action should be recognized.

An example involves the former governor of New York, Andrew Cuomo, who made the legalization of same-sex marriage a top priority for his state when he took office in January 2011. After the New York state legislature narrowly approved same-sex marriage six months later, Cuomo’s advocacy was widely credited for enabling this to happen (Barbaro, 2011). Other states legalized same-sex marriage, while some specifically outlawed it. This led to a Supreme Court case (Obergefell v. Hodges, 2015), and the federal decision to legalize same-sex marriage throughout the country.

Despite its great wealth, the United States ranks below most of its democratic peers on many social indicators, such as poverty, health, and so on (Holland, 2011; Russell, 2011). A major reason for this difference is that other democratic governments are far more proactive and collective-minded in terms of attention and spending than the U.S. federal and state governments are in helping their citizens.

A final source of change is the lessons learned from other nations’ experiences with social problems. Sometimes, these lessons for the United States are positive ones, as when another nation has tackled a social problem more successfully than the United States, and sometimes these lessons are negative ones, as when another nation has a more serious problem than the United States and has made mistakes in addressing this problem. The United States can learn from the good examples of some other nations, and it can also learn from the bad ones. In this regard, the United States has much to learn from the experiences of other long-standing democracies like Canada, the nations of Western Europe, Australia (figure 5.9), and New Zealand.

As human service providers, we have become the front line in many ways of communities that are impacted by systems that have been harmful to them by oppressive systems that have often blamed individuals for lack of “will” instead of those systems taking accountability for not being created or prepared to support the needs of diverse communities.

Our job as providers is to continue to expand how we look at welfare support systems to develop clients’ access to those systems sustainably through community interdependence and decrease shame when in need of support systems.

Licenses and Attributions

“Social Insurance Programs” is adapted from “Poverty and Financial Assistance” by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, Social Work and Social Welfare and is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce include light editing, vocabulary and context changes to adapt for the human services field. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 5.7. This image is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.8. “Protest against a constitutional amendment banning same sex marriage” by Fibonacci Blue is marked with CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5.9. “Parliament House Canberra” by Sam Ilić is marked with CC BY-NC 2.0.

a group of programs that take into account any contributions that the beneficiary has made to the program and may be considered preventative in nature.

well-being

a group of programs meant to alleviate the effects of poverty, and applicants must pass a means test in order to receive benefits.

a federal program established in 1935 to provide protection against poverty to older Americans.

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.

the joint federal and state-sponsored program aimed at providing medical care to lower income individuals.

the federal health care program in the United States provided to adults 65 and older as well as disabled citizens.

the state of lacking material and social resources needed to live a healthy life

an academic rank conferred by a college or university after completion of a specific course of study.

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

any condition or behavior that has negative consequences for large numbers of people and that is generally recognized as a condition or behavior that needs to be addressed. Multiple factors contribute to the complexity of social problems. Typically the solution to the problem needs to be systemic in nature; in other words, it cannot be solved by any one individual.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes, primary, and secondary reproductive organs.