7.3 Historical Context of Mental Health Treatment

At least as early as the 1200s, people with unpredictable or unusual behaviors were subject at times to institutionalization in Europe. As with many other elements of social welfare, a belief in this practice was carried over when Europeans colonized North America (Cox et al., 2016). Without a firm understanding of the nature of mental disorders, people were sometimes believed to be possessed or otherwise cursed in some way. Institutionalization was seen as necessary, for the individual’s safety or the safety of the community. Sometimes when people were believed to be possessed by demons, they were tortured in an effort to free them from their demonic captors (Zastrow, 2010).

People in need of care in the 1700s and much of the 1800s were often confined to unsanitary and overcrowded asylums, placed in “almshouses with criminals and degenerates,” or sometimes simply imprisoned (Farley et al., 2009, p. 153). Of course, there were no treatment facilities available when colonists first came to what would become America—the Native Americans did not have formal institutions, and the Europeans were working to colonize the country. Therefore, despite the fact that institutionalization was supported in theory by the European colonists, in practice it did not exist. People with mental disorders were, therefore, cared for by their families or left to survive on their own.

An early activist and crusader, Dorothea Dix, noticed during her time teaching classes to inmates at the East Cambridge jailhouse that criminals and those with mental disorders were being housed together, as though having a disorder were a crime to be punished (Wilson, 1975).

Dix, shown in figure 7.2, traveled the country and worked to alert the public to the horrifying conditions that people with mental disorders were enduring in these prisons and almshouses. She acted as an advocate for more humane treatment and penned the following account for the Massachusetts legislature:

I tell what I have seen—painful and shocking as the details often are…I proceed, Gentlemen, briefly to call your attention to the present state of Insane Persons confined within this Commonwealth, in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, pens! Chained, naked, beaten with rods, and lashed into obedience!…I have been asked if I have investigated the causes of insanity? I have not; but I have been told that this most calamitous overthrow of reason often is the result of a life of sin; it is sometimes, but rarely, added, they must take the consequences; they deserve no better care! Shall man be more unjust than God, who causes his sun and refreshing rains and life-giving influence to fall alike on the good and the evil? Is not the total wreck of reason, a state of distraction, and the loss of all that makes life cherished a retribution, sufficiently heavy, without adding to consequences so appalling every indignity that can still lower the wretched sufferer? (Wilson, 1975, p. 122–123)

Dix felt it was not cruelty but ignorance that caused people to treat those with mental disorders this way. Her passionate recounting of her discoveries to the Massachusetts legislature led to the passing of a bill in 1843 that charged the state with the proper and compassionate care of these individuals (Wilson, 1975). She went on in later years to lobby the federal government to give states land that could be devoted to the construction of facilities to properly care for those in need of mental health care. The attention she brought to the cause was a major impetus for improvements made over the next several decades in the mental health care system. In 1855, the Government Hospital for the Insane (later known as Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital) was founded by an act of Congress, and by 1860, 28 of the 33 states in the union at that time had constructed at least one psychiatric hospital (Torrey, 2014).

The Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital is the District’s public psychiatric facility for individuals with serious and persistent mental illness who need intensive inpatient care. However, although supportive in certain aspects, it was not immune to a prevailing issue that continues to impact mental health diagnosis and overall treatment: racism. The hospital began treating Black individuals who, at the time, were still primarily enslaved throughout the United States. As the hospital was situated in Washington, DC, a region whose population was around 20% of the Black population at this time, it also admitted Black patients.

However, the conditions offered to Black patients were markedly distinct from those afforded to their White counterparts. Hospital records indicate that Black and White patients were separated, with hospital staff contending that segregation was a necessary form of therapy for both Black and White patients. According to this rationale, White patients might encounter obstacles in their recovery if they interacted with Black patients.

White patients were accommodated in the center building, a brick structure featuring expansive wards. In contrast, Black patients were housed in smaller wooden lodges at a distance from the center building. These lodges were frequently overpopulated and would become incubators for disease. Black patients were also subjected to physical labor, such as digging trenches, building walls, clearing forests, and grading hills without access to the nutritious diets White patients were receiving. Although both racial segregation and occupational therapy were considered forms of moral treatment, they were implemented differently for Black and White patients (Gordon, 2024).

As we can see, the idea of “separate but equal” was in place even before Black Americans had been given their freedom—or rather, fought for their freedom and to be seen as fully human in this country. Yet we have benefitted from their bodies, souls, and experiences as we have learned many lessons from the clients at Saint Elizabeth Hospital about treatment and care. As human services providers, we must continue to undo systems of oppression that perpetuate these ideas of harm, such as “separate but equal.”

In the early 1900s, Sigmund Freud’s work brought to mainstream awareness the idea that mental disorders were truly illnesses and people suffering from them needed understanding and proper care to have a chance to recover. He pushed a very medical perspective of mental disorders, said that early childhood trauma had caused a lot of these individuals’ emotional and behavioral problems, and encouraged psychiatric diagnosis and treatment of individuals (Greenberg, 2013). This led to a more humanitarian approach, though some of Freud’s specific ideas were misguided (Zastrow, 2010; Greenberg, 2013).

At the same time Freud’s work was gaining steam, social work was also focused on those with mental disorders. Social work was offered as a service in both Manhattan State Hospital and Boston Psychopathic Hospital by 1910, and Surgeon General Rupert Blue asked the American Red Cross to get social workers involved in the federal hospital system in 1919: “by January 1920, social service departments had been organized in forty-two hospitals” (Farley et al., 2009, p. 154).

Despite the increased presence of social work in mental health care, conditions still left a lot to be desired. In 1943, conscientious objectors to the war (often religious young men) were put to work in other ways, some in state mental hospitals. They reported scenes much like Dix had seen in correctional facilities:

Here were two hundred and fifty men—all of them completely naked—standing about the walls of the most dismal room I have ever seen. There was no furniture of any kind. Patients squatted on the damp floor or perched on the window seats. Some of them huddled together in corners like wild animals. Others wandered about the room picking up bits of filth and playing with it (Torrey, 2014, pp. 22–23).

In 1945, following World War II, there was increased recognition of the impact of mental disorders on America’s troops. Government leaders wrote the National Neuropsychiatric Institute Act, a nationwide mental health program that became the force behind the foundation of the National Institute of Mental Health in 1949 (NIMH) (Torrey, 2014; Cox, Tice, & Long, 2016).

The proposal that the government take a more active role in treating those with mental disorders was fairly revolutionary. It included thousands of centers from coast to coast—at least one in each Congressional district. John F. Kennedy, who took the White House in 1961, was a powerful ally, as Kennedy’s sister Rosemary had undergone a lobotomy and become incapacitated, though this was not information freely shared with the public at the time. Rosemary had been diagnosed with what was then called (activation warning) “mental retardation” (now “intellectual disability” APA, 2022). That, conversations about mental health, was first on Kennedy’s agenda as president, but shortly thereafter he turned his attention to mental health treatment as well (Torrey, 2014).

By 1961, a committee appointed by the president had decided to push for the elimination of state mental hospitals, the deinstitutionalization of those with mental disorders, and the establishment of a network of community mental health centers (CMHCs), a plan approved by Congress in 1963 (Torrey, 2014; Frank & Glied, 2006). The plan provided federal funds to communities to build such centers and to get them up and running for a few years, with the expectation that each center would become economically self-sufficient thereafter.

However, the American involvement in the Vietnam War (1965–1975) severely curtailed the funding Congress had planned to provide. Congress simultaneously tasked the CMHCs with handling new groups of clients: substance abusers, children, and older adults (Frank & Glied, 2006). With these dual concerns, CMHCs had to keep costs down. This meant higher client-to-staff ratios and a pattern of treating people with less severe problems who were easier to help at a lower cost. This, of course, left those with more severe disorders again to public hospitals (Frank & Glied, 2006).

Deinstitutionalization, while well-intended, ended up having some notable negative effects. The desire to give people with less severe mental disorders a chance to be maintained in their communities on an outpatient basis wasn’t a bad one. However, the closing of many of the hospitals and the inability of CMHCs to pick up all the slack meant that many people with severe conditions did not actually have anywhere to go that could provide the level of help they required. This is often seen as a major factor in the rise of houseless among those with mental disorders, as well as the high proportion of the prison population (estimated at up to 20%) that have psychiatric problems (Frank & Glied, 2006; Torrey, 2014).

To complicate the problem further, prisoners with mental disorders are less likely to access follow-up care, more likely to end up back in prison than other prisoners, and on average return to the correctional system faster (Barrenger & Draine, 2013). By the 1990s, leaders in mental health came to the conclusion that while CMHCs were an important piece of the solution, well-regulated and well-staffed state mental hospitals were also an integral part of a system that could fully address the needs of citizens with mental disorders (Farley et al., 2009).

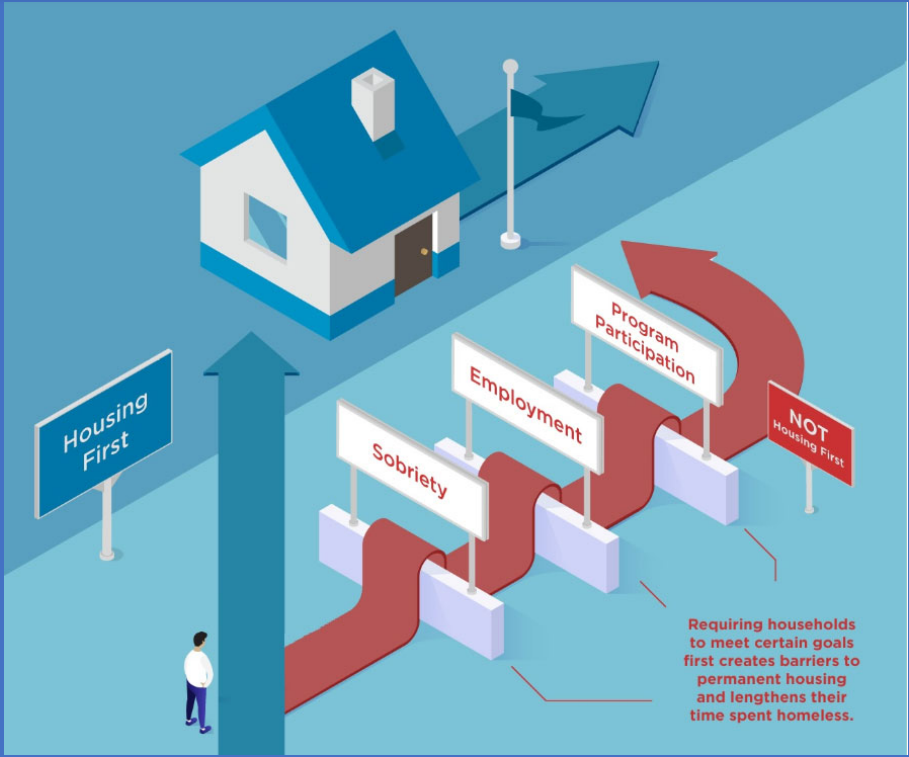

The deinstitutionalization movement left many people with mental disorders houseless and resulted in a lot of people with mental health disorders having nowhere to go but to the streets. To get into housing, they often had to restart medications, maintain sobriety, and participate in other programs that posed barriers to long-term housing, as indicated in figure 7.3. Housing first is currently the best approach to working with people experiencing severe and chaotic symptoms to help them transition into housing and provide support within the safety of a person’s own home.

Most recently, laws have been passed on a national scale to reflect the increased recognition of the importance of treating mental disorders with the same degree of attention and coverage that physical illnesses and injuries receive. The Mental Health Parity Act of 1996, along with the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008, require insurance companies to approach the treatment of mental health and addictions in the same manner as medical or surgical treatment. Companies may not put stricter lifetime limits, higher co-pays, or higher deductibles on someone’s plan for mental health or addiction treatment than the same person has for most medical or surgical treatments (United States Department of Labor, n.d.). Finally, under President Barack Obama, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 helped to expand Medicaid (now the nation’s number one source of funding for mental health care) and paved the way for more coordination between the professionals involved in medical and psychiatric treatment of people with mental disorders (Kuramoto, 2014).

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Historical Context of Mental Health Treatment” is adapted from “Mental Health and Treatment” in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: Minor editing for clarity; shortened sections and elimination of some disorders; updated; refocus of content on to human services. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 7.2 “Dorothea Dix” by exit78 is marked with CC PDM 1.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 7.3. “Housingfirst-powerpoint-graphic” by Kevin Anderson is reproduced under fair use.

well-being

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.

an academic rank conferred by a college or university after completion of a specific course of study.

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

the joint federal and state-sponsored program aimed at providing medical care to lower income individuals.