10.2 Finding Your Fit

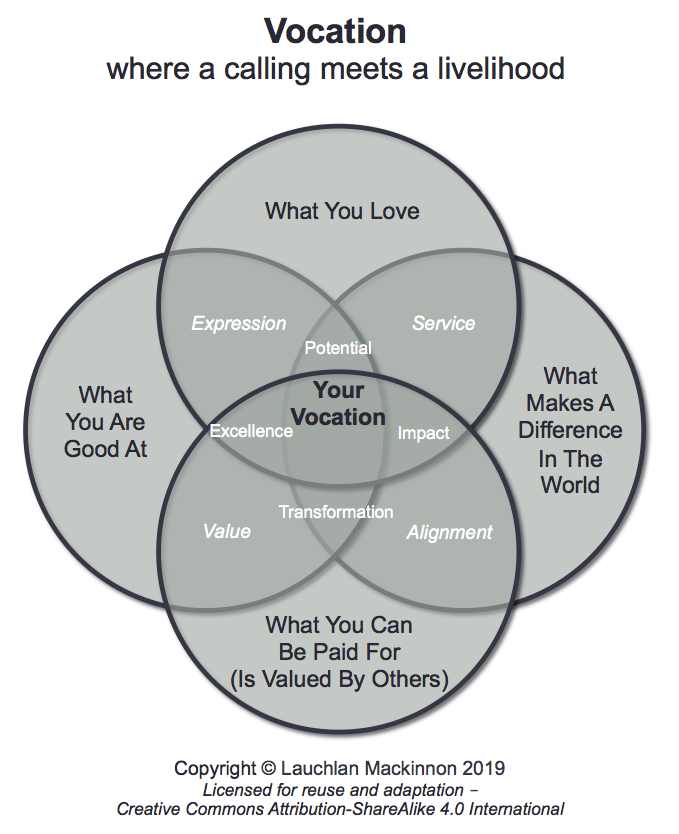

An important part of finding your place in the field is understanding your own goals and values. When you know these aspects of yourself, you can find an environment that reflects them. This environment includes not just the work you do, but the agency or agencies that you work within. Develop a good grasp on your own views and make sure you are aware of the goals and values of the organizations you are considering (figure 10.1).

Understanding Yourself

The first step in finding your fit is to have a deep understanding of what is important to you in the work that you do. You may want to find work in the field that reflects some of your personal strengths. For example, if you have an easy time establishing rapport with young people, you may decide to focus on finding positions that work with youth. In addition, you might enjoy being outdoors and find office work a bit repetitive. This could lead you to seek agencies that do field-based work with youth, such as residential treatment or wilderness-based programs.

In contrast, you may decide you want to focus on areas of growth. You may have years of experience working with small children, but now you’d like to work with a different age group. You may have become comfortable working in large bureaucracies and would like to understand more about working in a smaller community organization.

In addition to understanding your strengths and areas for growth, it is important to be realistic about your limitations. You may have obligations, such as family or spiritual practices, that limit your availability. You will want to focus on agencies that can work with your schedule. Another limitation faced by many students involves transportation. If you do not drive or do not have access to a car, you will need to focus on agencies that are near public transportation and work that does not involve home visits or traveling to other agencies. Some agencies have vehicles available for employees to use for client sessions and agency work.

Consider your preferences versus your non-negotiables. You may prefer a regular nine-to-five, Monday-through-Friday schedule, but you may not want to rule out positions that match your values and goals but require working weekends. However, you may have a religious practice that prohibits working on certain days or that has services that you feel are significant and cannot be missed. This would represent a non-negotiable. For example, you might receive a job offer upon graduation that is the exact position you are looking to secure, but with an agency that is located in a city 20 miles from your home. While you would prefer to work locally, you may decide the position itself is such a great match that an extended commute is tolerable.

Finally, you must also know how the work matches your worldview then focus on positions and organizations that match that view. This may include opinions about the field that involve macro-level policies, such as immigration or health care, or opinions that are more personal and on the micro level, such as abortion or LGBTQIA+ rights. Many of you have heard the phrase “separate the issue from the person,” but can we do that? Bias is so embedded in our choices and societal expectations that we sometimes don’t realize that we made our choices before we realize that we made our decisions because of their identities, not because of the issue that needs to be resolved.

Personal Values

The significance of personal values in shaping one’s worldview cannot be overstated, particularly in the human services sector. While social justice forms an integral part of this field, an individual’s values will significantly impact their professional identity, including the type of role and agency they choose to work with. This may require making difficult choices between competing values, such as selecting to work with an issue one is passionate about or an agency that aligns with one’s diversity values. This predicament is further complicated by personal and professional values often being interwoven and difficult to distinguish.

It is imperative to consider intersectionality when examining personal values and their impact on individuals. These values form the basis of one’s worldview and spill over into the professional domain. Therefore, it is crucial to carefully evaluate the influence of personal values and balance personal and professional values when making decisions. This balance is essential when personal values do not align with professional standards.

The alignment of personal values with professional standards is not just a consideration but an integral aspect of the human services field. Professionals must critically assess their values and their impact on their worldviews to make informed decisions when deciding between competing values. This alignment is a task that cannot be delayed or taken lightly, as it directly influences the quality of our work and the impact we have on our clients.

Positionality

Positionality refers to an awareness of our social identities and how those fit with others and within a power structure. It is important to engage in self-reflection and examine our identities to better understand ourselves and how others perceive us. Our privileges can greatly impact our interactions within the agency and affect how our clients and colleagues perceive us. Think about developing an awareness of the power structures within our agency and how they influence our daily interactions.

This awareness is not a solitary journey but a collaborative one. It can be nurtured through individual and group supervision, and by committing to an intersectional approach throughout our lives. This commitment involves intentional time and action while working together with BIPOC and White affinity colleagues in their affinity spaces to understand and respect their experiences.

Starting with race is essential, as it is one of the most significant factors and systems of oppression that we must consider when examining our positionality. It is also necessary to consider other factors, such as gender, sexual orientation, religion, and socioeconomic status, when reviewing our positionality.

By actively participating in these conversations and actions, we can foster a more inclusive and equitable workplace. It’s vital to remember that this is not a one-time task, but an ongoing process that demands continuous effort and a hunger for learning and growth. This commitment to continuous improvement is what will truly make a difference in your workspace.

A Personal Story: That’s Not What a Professional Looks Like

When I (Martha) first decided to apply for graduate school, I was told by a professor in my undergraduate program that I was not what a professional looked like. I should not waste my time applying for programs that don’t take people who wanted to do the kind of “passion projects” that I wanted to do or had life experiences that “don’t fit with what the field needs.”

This would not be the last time that my version of professionalism would be put into question or asked to change to fit into a more “appropriate” way of acting. These ways were always centered around my appearance, how I sounded, whether my knowledge came from “the right place,” or how I wanted to use my cultural experience to support my community’s needs. I was often asked why I always wanted to bring up race or why I needed to ask questions about diversity, equity, and inclusion in every conversation. “That is not what this meeting is about,” I was often told.

This would be a pattern that I would deal with in my career, and allies would be necessary. I had to find people who could understand my story so I would not be alone in the experience of being a child of immigrants trying to navigate the world that had systemic barriers to block me from entering it.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1QlM5cJGimA

As I searched for understanding, I yearned to meet people who shared my appreciation for my parents’ intelligence and strength despite their sometimes heavy accents. I longed to find individuals who recognized that my parents’ accents were not a reflection of their intellectual capacity but a testament to their ability to read, dream, sing, speak, protest, pray, and create an entire world in a language that others in our new community could not.

Their accents reminded my parents of their sacrifices when they left their home country to give their daughters a chance to thrive in a foreign land where their education and skills would be valued. My parents were determined to provide a brighter future for their family, whether they were practicing nurses or civil engineers in another country. And yet they carried with them the rich cultural heritage of their homeland and a deep love for the language that defined their identity. They (the world around us) could see my parents’ deep-brown skin, which was sun-kissed by Huitzilopochtli, the Nuhutl sun god, as a gift, not something that was scary.

Professionalism: Ten Ways White Supremacy Lied to Us All

When asked to describe a professional, it should not include the color of someone’s skin or cultural experience; that perspective only comes from one cultural experience. A professional is someone with a skill set used in a specific field. These skills could come from a formal educational setting, from your own life experience, from internship experiences, or from traditional cultural learning.

This does not include a specific way of dressing, which is usually one of the ways that professionalism is pushed onto students. This can limit what people think they need to look like or be in order to be considered a professional. The ideas that are being forced on many students in educational settings about professionalism are centered around White supremacy culture. Tema Okun talks about ten ways in which this shows up (Jones & Okun, 2001; Okun, 2021):

Perfectionism: Expressing appreciation for the work of others is often overlooked. When it is expressed, it’s usually directed toward those who already receive most of the credit. It’s more common for people to point out someone’s inadequacies or flaws rather than recognizing their positive qualities or good work. Even worse, talking about someone’s shortcomings to others without addressing the person directly is prevalent.

Mistakes are not personal failures; instead, they are integral to the learning process. They should not be seen as a reflection of one’s worth but as opportunities for growth and learning. It’s crucial to focus on reflection and identify lessons that can enhance performance; otherwise, mistakes will not be used as stepping stones for personal development.

There’s a tendency to focus on what’s wrong rather than right, which makes recognizing and appreciating positive contributions difficult. This tendency causes people to feel inadequate and struggle with a harsh inner critic. They might overlook their excellent work and instead focus on their failures and mistakes.

Sense of urgency: In any organization, it’s essential to prioritize inclusivity, democratic decision-making, long-term thinking, consequence evaluation, and learning from mistakes. It can be challenging to maintain this focus when there is a constant sense of urgency. In such situations, there is a risk of neglecting potential allies in favor of quick or visible outcomes.

For instance, sometimes the interests of communities of color may be overlooked to expedite success for White individuals. This urgency is further perpetuated by funding proposals that demand excessive work for inadequate compensation from funders with unrealistic expectations. To overcome these challenges, it’s crucial to balance urgency and inclusivity. This can be achieved by involving all stakeholders in the decision-making process, being mindful of the long-term impact of our actions, evaluating the consequences of our choices, and being open to learning from mistakes.

Defensiveness: Although an organization may have a clear structure, there is still an opportunity to cultivate the potential of each individual and clarify power dynamics. However, some may prioritize maintaining the status quo and preventing abuse over introducing innovative or challenging ideas.

Promoting a culture of open-mindedness and encouraging constructive criticism is essential to bring about positive change. By investigating how racism manifests in the workplace, the organization can take steps toward creating a more inclusive environment. Leaders should interpret calls for change as opportunities to improve rather than personal attacks, which can empower people to effect change. A constructive approach can help the organization achieve a more positive and inclusive future.

Quantity over quality: Optimizing available resources and attaining measurable outcomes can be seen as imperative to achieving organizational goals. Quantitative measures take precedence over non-quantifiable ones. For instance, meeting attendance, newsletter distribution, or incurred expenses are prioritized over relationship quality, democratic decision-making, or conflict-resolution skills.

Processes that cannot be measured are not valued. Emotional factors are consistently ignored. The prioritizing process is in a conflict between content (such as a meeting agenda) and process (like participant engagement). Without prioritizing non-quantitative measures, decisions made during such a meeting may be disregarded or challenged, even if the agenda is accomplished.

Worship of the written word: Many organizations consider formal information documentation through memos valuable. However, other methods of sharing information can be equally effective. While strong writing and documentation skills are highly regarded, interpersonal skills are also crucial to success.

There is only one right way: It emphasizes the importance of clearly understanding the most effective approach to a task. It also emphasizes the significance of being open to new ideas and willing to modify one’s behavior. Everyone has a unique perspective, and each person’s input can be valuable. We should strive to appreciate diverse viewpoints and learn from them. This approach fosters a collaborative and inclusive environment where everyone is valued and respected.

Paternalism: Effective decision-making requires transparency and consideration for all perspectives involved. Those in positions of power should recognize that their decisions can impact those without power and try to understand and incorporate their viewpoints.

On the other hand, those without power may not need to comprehend the decision-making process entirely, but they do need to be able to voice their concerns and provide feedback. We can make more informed and equitable decisions by working together and valuing diverse perspectives.

Either/or thinking: When we view things as either/or, we limit ourselves to only two options and disregard the possibility of alternative solutions. This can oversimplify complex issues and create conflict and urgency.

Instead, we should adopt a both/and approach that allows us to consider multiple perspectives and generate creative solutions. By embracing this mindset, we can avoid oversimplification and work toward finding more effective and sustainable solutions. Complex problems often require time and resources to solve, and we should be open to considering all possible options before deciding.

Power hoarding: Encouraging open communication and collaboration among team members is necessary to foster a more inclusive and effective decision-making process. Sharing power with those in leadership positions can also lead to a more balanced and constructive organizational structure. Additionally, providing team members with training and resources to develop their leadership skills can help them become more effective agents of change.

A culture of trust and respect is essential to creating an environment where team members feel secure and valued. Such an environment encourages them to share their ideas and concerns without fearing retribution. The emphasis of the significance of diversity and inclusivity, as these values can contribute to a more prosperous and sustainable organization.

Fear of open conflict: It is common for individuals in positions of authority to avoid confrontation. When a challenging matter is raised, the automatic response frequently assigns fault to the person presenting it rather than addressing it. There is a tendency to maintain a veneer of politeness, even when policies or actions are deeply painful or offensive to those impacted. This emphasis on etiquette can stifle conversations or negotiations, leaving individuals to suppress legitimate feelings of anger or frustration. Furthermore, intricate issues may be dismissed as impertinent, discourteous, or inappropriate, impeding the search for meaningful solutions.

When walking into a classroom, agency, or interview, you may be the only one who looks like you, has your stories to tell, comes from spaces that you were once not allowed in and others may not even consider asking about. You may be treated differently or not even be recognized as a professional in the space. It’s frustrating, but not unusual, to hear people say, “Are you the interpreter?” “It is not professional to wear those earrings in the office.” “You don’t look like any instructor I have seen teach here before; can I see some ID?”

Organizations and Associations

Transitioning from a student perspective to a professional one involves commitment to the profession of human services itself. Being part of a profession—a career that requires education (formal, informal, non traditional, traditional), formal training and degrees or certifications—means that you will adhere to a code of ethical standards, commit to lifelong learning, and strive to continue the development of human services. This can include activities such as attending professional conferences, reading, discussing, or even conducting research, advocating for legislation, and belonging to a professional organization. Listed below are three common professional organizations that even students can belong to:

- National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) [Website]

- National Association of Social Workers (NASW) [Website]

- National Council on Family Relations (NCFR) [Website]

You can join the associations above as a student and evolve into being part of them as a professional. The cost associated with these organizations is lower for students than for professionals after being licensed or even retiring. Each organization has a code of ethics members abide by. As stated before, ethical codes are not the same as laws and cannot be enforced by associations in the way that laws are enforced by governments, just encouraged by the associates.

As members of these organizations, it is up to us to keep our field’s values aligned. In Chapter 4, we discussed ethics and how intersectionality needs to be considered for every code we are thinking about. But what if the membership of these associations is less diverse than the clients their members serve? What can students and instructors advocate for to support the increased diversity of the field?

Consider how we look at human services recruitment, how we look at the occupations that we include in our field, and how we look at mentorship in the field. All of these questions help us build plans to continue to diversify a field that, at this time, does not reflect the communities that it supports.

Licenses and Attributions

“Finding Your Fit” is adapted from Finding Your Fit by Yvonne M. Smith, LCSW, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 10.1. Light bulb drawn on a clear board with a black marker by Defense Visual Information Distribution Service is in the Public Domain.

Figure 10.2. Vocation by Lauchlan Mackinnon is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Figure 10.3. Epistemic injustice in healthcare | Wellcome by Wellcome is licensed under CC BY 3.0 Unported.

Figure 10.4. Huītzilōpōchtli by Gwendal Uguen is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0.

Figure 10.5. At School by Jean-Marc Côté is in the public domain.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

viewpoints and efforts toward every person receiving and obtaining equal economic and social opportunities; removal of systemic barriers.

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

awareness of your own social identities and how those fit with others and within a power structure.

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity

the conduct, qualities, and qualifications recognized as part of a profession.

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

a credit class in which students apply theory to practice by using what you have learned in coursework in a real world setting with a supervisor/mentor who is invested in the student’s growth and development.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

the act of working with others.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

moral principles.