1.4 Characteristics Needed for Human Services Work

As often as lists have been created, so have the list of characteristics that make the “perfect” candidate for human services provider. This book will attempt to do the same, while acknowledging that no one list will satisfy everyone or cover every need. Still, these characteristics are broad enough to cover the needs of many areas in the field and can fit the different micro, mezzo, and macro levels.

These skills can be used for therapeutic, preventative, and even systemic work, and they can look different for individuals depending on intersecting identities. The idea of looking for perfection is an idea of White supremacy that we as a human service field need to help break as it sets unrealistic expectations. We need to allow flexibility in what human service workers can look like based on the context and communities we are working in.

Empathy

Empathy is often described as putting yourself in somebody else’s shoes. While this description is helpful, empathy in helping is more intentional than this saying implies. Professional empathy is being able to look at the client’s issue or situation from the client’s point of view. You are attempting to see the world through the other person’s lens, but it does not mean that you can then know exactly how the client is feeling. It does not mean that you agree with this point of view or that you have had a similar experience to the client.

In fact, if you have had a similar experience, it may be tempting to say, “I had the same thing happen.” Remember that even if you have been in the same position, this does not mean you both see the situation the same way. Empathy shows that, as another human, you are trying to understand how the client views their experiences and situation. This involves maintaining a judgment-free approach to your work.

For example, let’s think about a human services student interning as an intake worker at a diversion facility for recipients of DUI infractions. The student may hear many versions of “I only had two drinks,” “I wasn’t impaired at all,” or “Everybody I know drives home after parties. I think they singled me out unfairly.” The student may not agree with these statements, but can the student understand how the client may view the situation? Developing your ability to view the situation from the client’s point of view is critical to working effectively.

Another way of looking at empathy is to consider these four elements:

- Perspective Taking: When you share or take on the perspective of another person, you must also be able to recognize someone else’s perspective as truth.

- Being Nonjudgmental: When you judge another person’s situation, you discount their experience. To take on the perspective of another person, you must put away your own thoughts, assumptions, and biases.

- Recognizing Emotions: Recognizing someone else’s emotions or understanding their feelings requires you to be in touch with your own feelings and to put yourself aside to focus on the person in distress.

- Communicating Understanding: You should be able to express your understanding of the other person’s feelings and ask them to tell you more (Wiseman, 1996).

Being compassionate with clients involves using empathy rather than sympathy—two behaviors that can be confused. While empathy requires seeing things from another’s perspective, sympathy involves seeing things from your own perspective. Empathy helps build connections between people, whereas sympathy puts one person (the one expressing sympathy) apart the other person, creating disconnection.

Activity: Empathy

Dr. Brené Brown is known for her work related to empathy, shame, and sympathy. In this three-minute video, she gives examples that distinguish empathy from sympathy.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KZBTYViDPlQ

After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- What are the differences between empathy and sympathy?

- How does empathy fuel connection?

- What does it mean to “silver line” something?

Congruence and Unconditional Positive Regard

Congruence (also known as genuineness) has to do with how a helper presents themselves. It is vital that the client feels that the worker is being real with them rather than just playing a role. As fellow humans, we intuitively understand this. Think of a time when you were asking someone for help. Your gut tells you when someone is being “fake” or doesn’t care about the situation. When congruence is being considered, we must also be flexible when thinking about neurodivergent clients and providers who have different cultural needs. Not all clients process emotions both internally and externally the same way, and this alone should give us a moment of pause. What preconceived notions do you have? What are some things that need to be unlearned about what emotional responses look like? How did you learn to show specific emotional reactions?

Just as we are sensitive to insincerity, our clients can pick that up in a human services worker. The solution is to find the balance between your everyday life and your working life. It doesn’t mean telling your every life story to a client, but it does mean being comfortable in your role of helper. This involves the development of boundaries that allow you to be your true self in your working relationships but maintain a constraint between your personal and professional life. We will discuss self-disclosure in more detail later in this book. When we consider congruence, two things of note are social expectations of how someone “should” express or feel during a particular situation and differences in cultural considerations. These will affect how a provider or client may experience or present themselves in an experience. Some ways social expectations lenses are impacted could be because of neurodivergence, developmental trauma, or even language barriers; the reasons are endless. The key to aligning your intentions with your expression is to have a genuine relationship and connection with the client. Clients sometimes say, “You are paid to care,” which brings us to unconditional positive regard for those client-provider relationships.

Unconditional positive regard means that everyone has worth and deserves our consideration simply by the fact that they are human. We come to each client and each relationship with a sense of respect and warmth regardless of the client’s past or current attitudes or behaviors. By meeting the client on this level ground, you are inviting the client to work with you as an equal partner in creating solutions. As with empathy, this requires the suspension of judgment of our clients. The term unconditional positive regard was coined in 1956 by clinical psychologist Carl Rogers expanding on the work of Stanley Standal in 1954.

Activity: Self-Assess Your Strengths and Challenges

Each person who enters the human services field brings their own set of strengths and challenges. This activity asks you to think about the strengths you already have and about the areas you might want to improve.

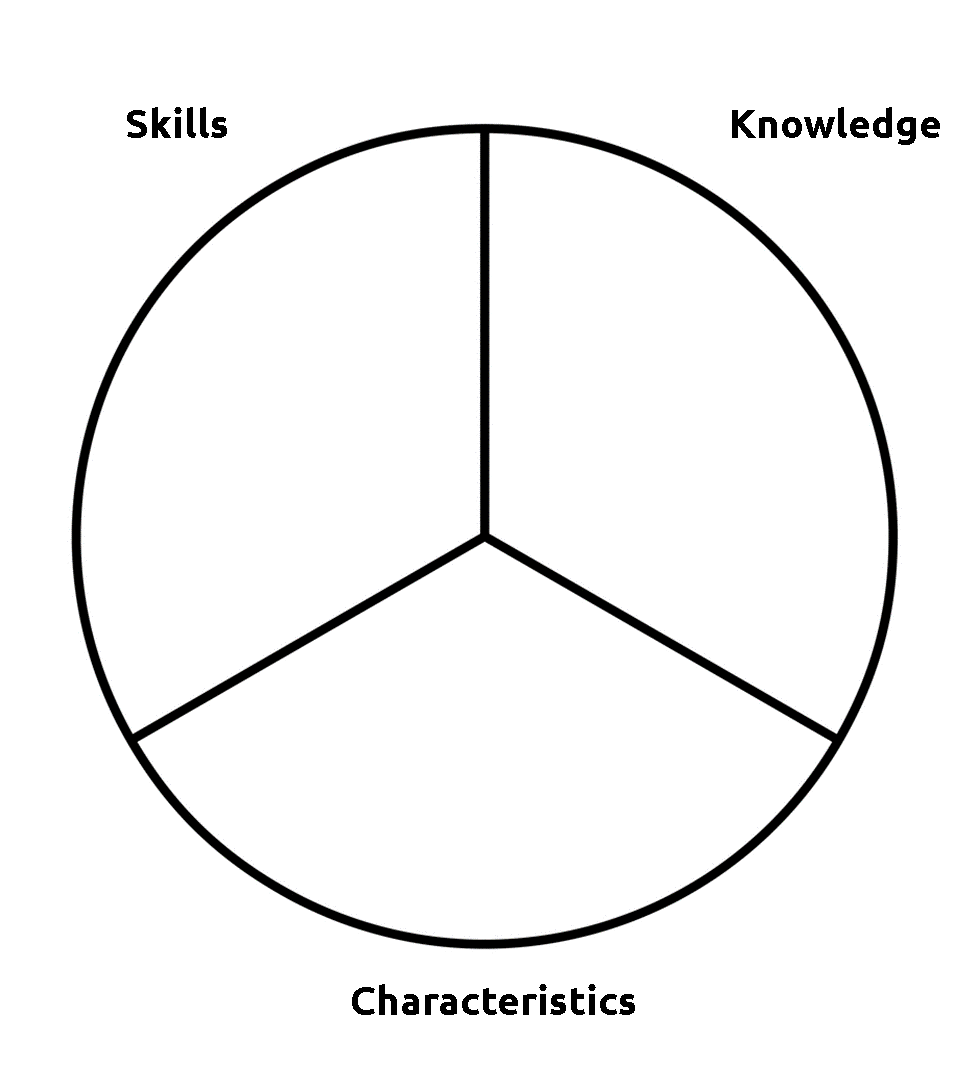

On a piece of paper, draw a circle and divide it into three sections. Label the sections “Characteristics,” “Skills,” and “Knowledge,” as shown in figure 1.12.

Review the following list of skills, characteristics, and knowledge, and write those you feel confident about in the matching section of the circle. Now, outside each section, write some of the attributes that you would like to strengthen.

Characteristics

- Patience

- Flexibility

- Curiosity

- Understanding of Self

- Community Care

- Attunement

- Humility

- Empathy

Skills

- Communication Skills (Oral, Written, Artistic, Listening)

- Documentation Skills (Objective Observations, Assessments, Qualitative Data Gathering, Quantitative Data Gathering)

- Ability to Ask for Help (Self Reflection, Group Reflection)

- Cultural Humility and Navigation

- Critical Thinking

Knowledge

- Awareness of Equity, Inclusion, Justice, and Diversity

- Understanding of Lifespan Development

- Theories of Effective Helping

- Knowledge Specific to You and Your Role

- Intersectionality

- Restorative Justice

- Ethical Code of your Profession

For example, you may feel very confident in your ability to empathize with others but know that you can be impatient. You would write “empathy” in the “Characteristics” section of the circle and “patience” on the outside of the circle. You can include other areas of strengths and challenges that you feel are important. For example, you might write “bilingual in Russian” in the section on knowledge, or “understanding of ADA laws” outside that section.

Each of us will have a unique circle that reflects where we are in our journey. It is important to realize that we all have areas where we are strong but that we all also have areas for growth. If you are able, compare and contrast your charts with a classmate or two. It can be interesting to see the wide variety of backgrounds that are present.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

“Characteristics Needed for Human Services Work” by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 1.11. “Empathy versus Sympathy” activity by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 1.12 “Knowledge, Skills, and Characteristics” by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

being able to feel and relate to another’s feelings.

being “real”; actions in line with values and beliefs.

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

belief that everyone has worth and deserves our consideration.

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities

an alternative approach to criminal justice that centers the survivor, taking into account what they need to experience healing. It also involves the participation of the perpetrator, requiring them to recognize the harm they did in the process of holding them accountable.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.