2.3 Integrating and Honoring BIPOC Contributions

In addition to individual scholars, many human services, social work, and advocacy organizations have worked to bring increased recognition to the roles of BIPOC in recent decades. For example, the National Association of Black Social Workers (NABSW) created the Academy for African-Centered Social Work. This organization emphasizes that the work of people of African ancestry has been excluded from social welfare history and from mainstream social work pedagogy and curricula.

Marginalization of past and present BIPOC social workers seriously minimizes their potential contributions to inform and strengthen current policy and practices.The NABSW has challenged the discipline to diversify curricula. They assert that failing to intentionally diversify educational materials leaves students to assume the main contributions to the discipline are White, which overtly and covertly reinforces White supremacy (Bent-Goodley et al., 2017).

The Role of Education

One approach to holding up the contributions of BIPOC lies in education. Currently, social welfare-involved work is not taught with an understanding of the ways that White supremacy is interwoven in its history. It seems that few social work education programs have exposed and dismantled the concept of the “great White hope,” yet this work needs to be done. Not only does there need to be a revision of who the discipline bestows the honor to as founders, but there also needs to be a greater understanding of ensuring that what is defined as social work or human services works. There needs to be a revision of what educational standards are and the Eurocentric lens used to measure them, as this continues to perpetuate White Supremacy (Wright et al., 2021).

For example, Jane Addams supported the eugenics movement and its scientific racism, which grew during the early twentieth century. It promoted the propagation of “wellborn” people and the prevention of childbearing among those who were determined to be defective mentally, morally, or physically (Kennedy, 2008).

Historical analysis of social welfare work’s White forerunners must also address the fact that Black activists and social services leaders of the Progressive Era were sidelined (McCutcheon, 2019). It is possible to see those identified as “founders” for what they were: individuals who sought to make change in one area of injustice while perpetuating injustice in another area. Maybe the answer is not to make them “angels” or “demons” but to live in the tension of their realities and what they prioritized. It requires telling their stories in the history books in light of such frictions.

It also calls for a radical review of who should be embraced as a founder of a discipline that is committed to equity and that “include[s] respecting the dignity and welfare of all people,” as stated in the Preamble of the National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) and the “inherent dignity and worth of all persons,” a principle embedded in the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics (NOHS, 2019; NASW, 2021).

Understanding and Dismantling White Supremacy

To dismantle White supremacy, we will focus on three aspects relevant to the human services profession’s understanding of history. First, White supremacy focuses on the written word. In the White culture, if it is not written down, it did not happen (Okun & Jones, 2000). This mantra is learned in most helping professions. Addams and her contemporaries came from a majority culture that valued the written word, and so they richly documented their research, observations, conversations, and findings. In contrast, many BIPOC come from traditional settings where such an effort is a luxury in comparison to focusing one’s energies on survival, especially in Addams’s time period. Communities frequently shared knowledge in many areas, as represented by, including how to help others. These are the foundations of the human services profession.

The second highly relevant aspect of White supremacy that contributes to the marginalization of BIPOC is the belief that there is only one right way to do things (Okun & Jones, 2000). It is necessary to consider whether the identified founders of social welfare incorporated the opinions of marginalized peoples in their work, continued to perpetuate the oppression, and embodied the “one right way” of doing things.

Individualism is the third relevant characteristic of White supremacy. To single out Addams as a founder is to add to the White supremacist notion that highly prizes individualism (Okun & Jones, 2000).

Individualism focuses on the advancement of one person rather than the collective whole. This contributes to an atmosphere where cooperation is less valued. Monuments for (some) racial advancements are dedicated to Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. Likewise, there is a focus on Martin Luther King Jr. as an individual leader, while it is commonplace in the Black community to think of him as synonymous with his collaborator. However, we do know that the contributions of these Black community leaders have different weight depending on how accurate of U.S. history lessons you are receiving. As human services professionals of any background, we need to embrace more than just White ways of perceiving and seek to call attention to communal contributions to our discipline.

How Can Students Make a Difference?

As a beginning student in this profession, you’re starting to understand the potential significant impact you could have in the field. Here are some roles you can play:

- It’s crucial to become aware of the whitewashing of the discipline. Don’t accept the single story of the discipline at face value. Instead, when a story is being told, ask to consider the other perspectives that have contributed to the field.

- Learn more about BIPOC scholars who are not well known and who have made a significant impact in the human services field and associated fields.

- Advocate for a more diverse representation of scholars in your course materials. Consider knowledge from sources outside academic ways of knowing. Look for traditional ways of knowing, such as Native storytellers, elders from BIPOC and marginalized communities, and oral traditions. This will help expand the ways we look for and absorb information.

- Continue questioning assumptions about what’s important and valued within the discipline.

- Diversify learning methods, teachers, and sources. What does a classroom setting look like? Who do our educators look like? Look at educator programs and recruitment, what does the student community and life look like?

Textbooks matter. A failure to accurately depict the past will slant how the future is framed. Without critical analysis, this slant will only continue to perpetuate White supremacist mindsets. Start paying attention to textbooks in all of your courses. Do you notice other places where the context of White supremacist history is ignored? Vigorous work by educators, researchers, and practitioners is needed to stop reusing the same publications and intentionally attempt to present the history of social work equitably.

Consider the authors of textbooks, including their history and bias. How often do you see yourself reflected in books and stories? Consider the publishers who own the textbook companies and their interest in the materials that are and do not include what is written in the content. How relevant is what you are reading to your practice in the field? Can you give feedback about what you are reading? How is that feedback received? You have more power in this process than you think. Use it.

The next section of this chapter focuses on skills and knowledge that can be used to work in a way that focuses on community strengths and values while emphasizing diverse voices and viewpoints.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Integrating and Honoring BIPOC Contributions” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “The Whitewashing of Social Work History: How Dismantling Racism in Social Work Education Begins With an Equitable History of the Profession” by Kelechi C. Wright, Kortney Angela Carr, and Becci A. Akin in Advances in Social Work, Vol. 21 No. 2/3 (2021): Summer 2021-Dismantling Racism in Social Work Education is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: Edited for brevity; slight reorganization of content; contextualized for human services; revised reading level. Added the following content: protestant work ethic, worthy/unworthy poor, and cultural humility concepts.

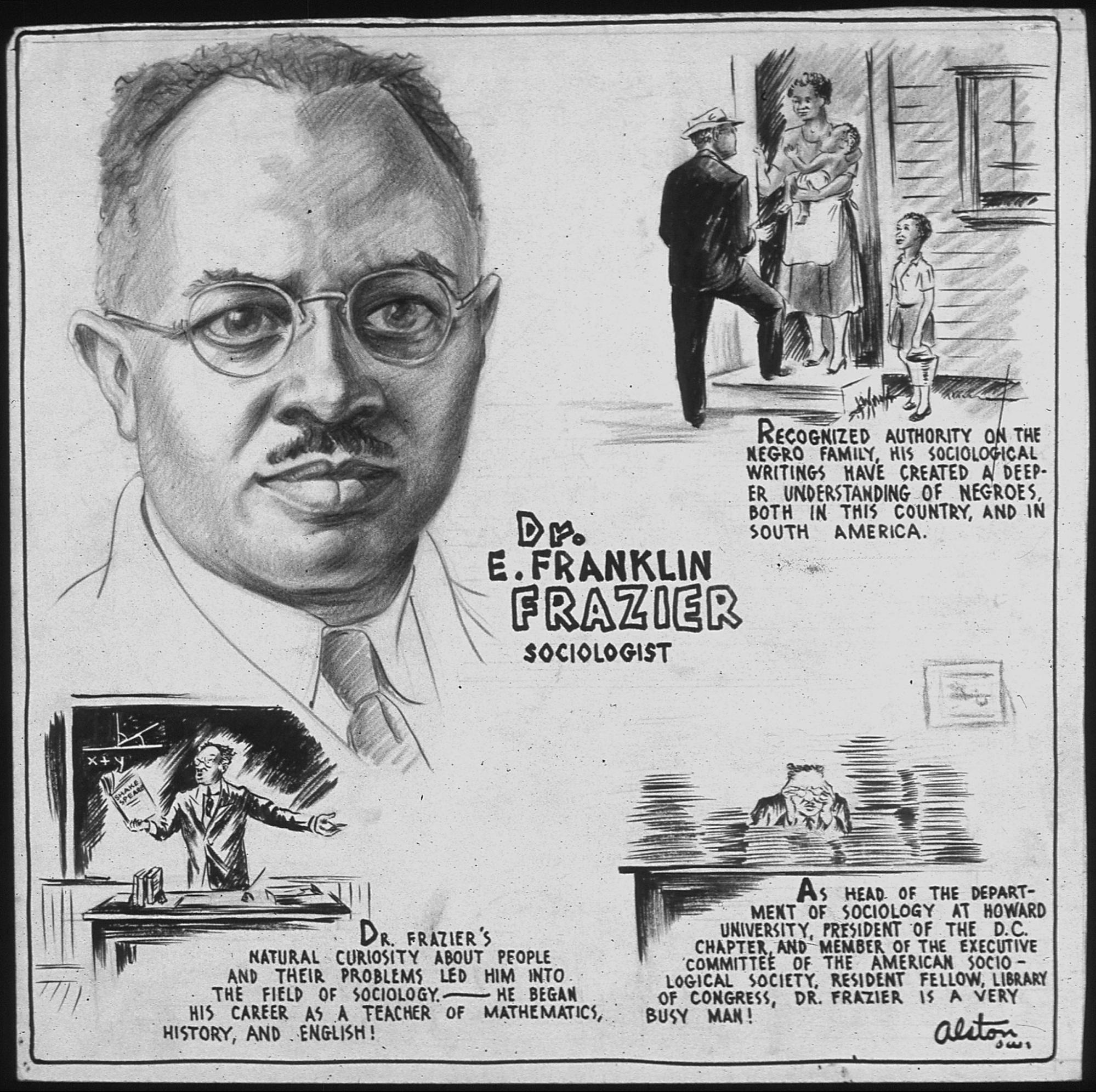

Figure 2.2. “E. Franklin Frazier” by Charles Henry Alston. U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Public domain.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

well-being

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

develop strategies that fend off problems

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

moral principles.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

focusing on the accomplishments of White people and groups,and excluding BIPOC strengths and accomplishments