2.4 Diversity and the Human Services Profession

The first two parts of this chapter focused on how an inaccurate past affects human services students, clients, and professionals, as well as ways to reinterpret the past to bring more truth about how communities of color impacted the field of human services. In this section, we describe some of the skills and understandings that have emerged as best practices.

To begin, let’s discuss the major dimensions of diversity, or the aspects of social identity that all of us possess. It is one step toward creating a more just future for all of those participating in human services and social welfare.

Dimensions of Diversity

Respect for diversity has been established as a core value in human services. In fact, the preamble of the Ethical Standards of Conduct refers to diversity twice in the opening paragraphs. Appreciating diversity includes understanding dimensions of diversity and how to work within a wide range of individual and community contexts. It also includes a consideration of how to work within systems of inequality.

Human services professionals must be mindful of diverse perspectives and experiences when working with clients, consulting with peers, conducting research, and designing interventions. At the same time, they must be aware of the macro-level problems that people face and work to combat oppression and promote justice.

Although it is impossible to discuss all of the dimensions of human diversity in this section, we present some common dimensions that are also aspects of each person’s social identities.

Culture

While numerous definitions for culture are available, key defining components include shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group that are passed down over time with each generation. That is, cultures have shared beliefs, values, practices, definitions, and other elements that are expressed through family socialization, formal schooling, shared language, social roles, and norms for feeling, thinking, and acting (Cohen, 2009).

Culture in today’s society refers to more than just cultural and ethnic groups. It also includes groups who are connected via religion, sexuality, geography, or other characteristics. Culture can be examined on multiple ecological levels to understand its impact. This means that culture can influence the norms and practices of individuals, families, organizations, local communities, and the broader society. For example, cultural influences can have an impact on how members function and interact with one another. Culture should be understood within a broader context of power relationships, as well as how power is used and distributed (Trickett, 2011).

Race

While physical differences often are used to define race, there is no consensus for this term. Typically, race has been defined using observable physical or biological criteria, such as skin color, hair color or texture, facial features, etc. However, biologists, anthropologists, psychologists, and other scientists have determined that these biological assumptions of race are false and have been used to harm members of marginalized groups.

Research has proven that there are no biological foundations for race and that human racial groups are more alike than different. In fact, more genetic variation exists within racial groups rather than between groups. Therefore, racial differences in areas such as academics or intelligence are not based on biological differences but are instead related to economic, historical, and social factors, such as the search for power and control via colonization (Betancourt & Lopez, 1993).

Race has been socially constructed and has different social and psychological meanings in many societies (Betancourt & Lopez, 1993). In the United States, Black, Indigenous, and people of color experience more racial prejudice and discrimination than White people. The meanings and definitions of race have also changed over time and are often driven by policies and laws. The social construction of difference in both race and gender is discussed more thoroughly in the next section.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity refers to one’s social identity based on culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group. Ethnicity is not the same as nationality, which is a person’s status of belonging to a specific nation by birth or citizenship (e.g., an individual can be of Japanese ethnicity but British nationality because they were born in the United Kingdom). Ethnicity is defined by aspects of subjective culture such as customs, language, and social ties (Resnicow et al., 1999).

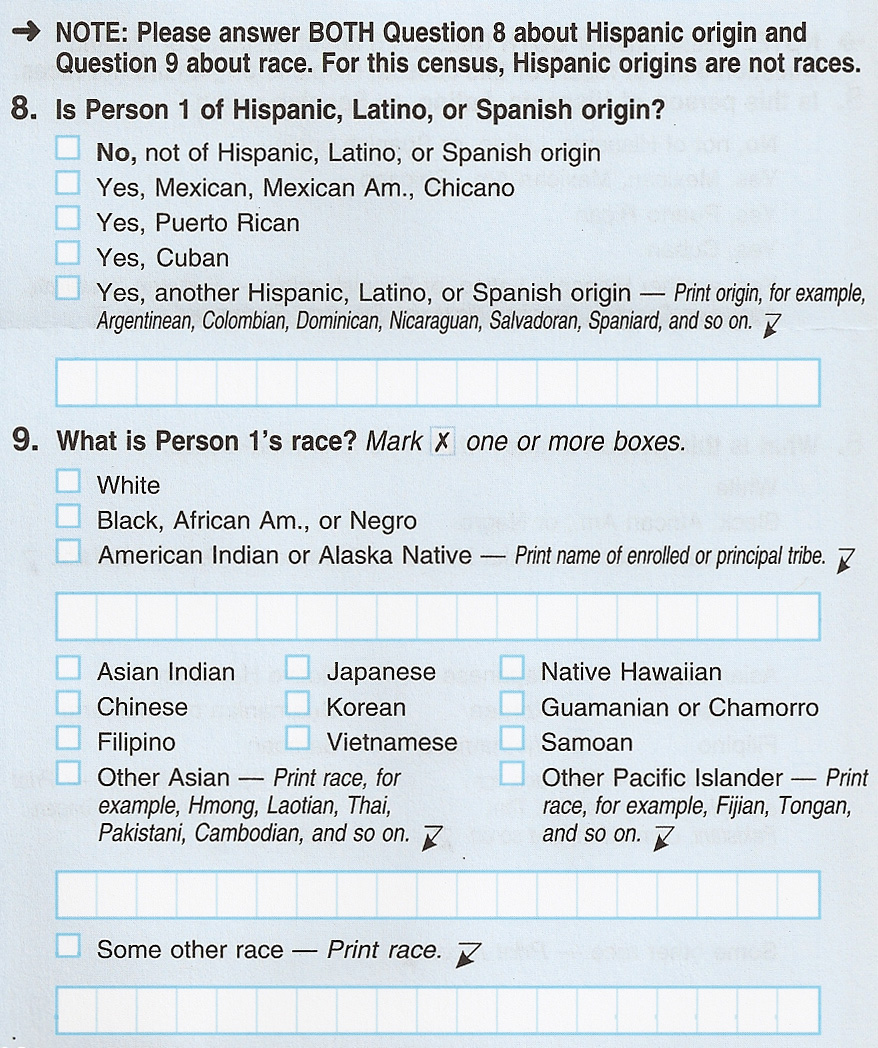

While ethnic groups are combined into broad categories, or umbrella groups, for research or demographic purposes in the United States, there are actually many more specifically defined ethnicities that do not appear on documents. For example, there may be a check box for “Latine,” but people who are in this umbrella group are more likely to identify with a specific country, region, or nationality. Latine may refer to persons of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Spanish, Dominican, or many other ancestries. Asian Americans have roots from more than twenty countries in Asia, with the six largest Asian ethnic subgroups in the United States being Chinese, Asian Indians, Filipinos, Vietnamese, Koreans, and Japanese, as indicated in figure 2.3.

Origin and First Language

Origin refers to the geographical location where a person was born and spent at least their early years. This includes regions of the United States as well as other countries. A person’s origin will impact the cultural norms that influence them during their early childhood development, or perhaps longer. In addition, it impacts their first language.

First language refers to the language learned in early childhood. This language may be learned in the home, in a childcare setting, and in greater society. Even within the United States, there are regional differences in the English language, as well as the possibility that a language other than English is spoken in the home. Consider that the United States does not have an official language, not even English (USAGov, n.d.). Given this fact, English might not be a person’s first language, even if it is heard and seen around a lot.

Origin and first language are closely tied to culture and ethnicity, but there are differentiations as well. For example, a Filipino person may have grown up in the Philippines, but they could have been born in the mainland United States or in Hawaii. In the Philippines, where the official languages are English and Filipino, there are 183 living languages, many of which are indigenous. A person growing up there might speak one or more of these languages. A Filipino person growing up on the mainland of the United States would likely learn English, but they may also use a Filipino language at home. A Filipino person growing up in Hawaii might be exposed to English, Hawaiian (although the indigenous language of the islands was banned in 1898 when Hawaii became a territory of the United States, there are still remnants), and a Filipino language. Because the Hawaiian language and the Filipino language are from the same language family, there may be crossover. As this example shows, great diversity exists even among people who share a similar origin or first language.

Consider how language evolves within a single language. If your first language is Spanish but your family is from Mexico, you may understand the Spanish spoken in Argentina to an extent. However, the accent, the words specific to that country, and the context from the specific culture make an impact on how the language is spoken and understood by its speakers and those who are supporting those communities.

Gender and Sex

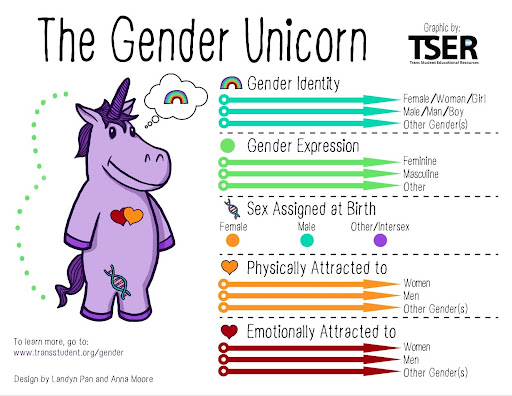

Gender refers to the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female, or nonbinary in the way you present to society. In the past it was more common to see gender in a binary way, either male or female, but increasingly gender is seen more on a continuum.

Gender is different from sex, which is a biological descriptor involving chromosomes as well as internal and external reproductive organs. Sex is also less binary than we might expect. A small percentage of people are known to be born as “intersex,” meaning that they have primary and secondary sexual characteristics that are both biologically male and biologically female. However, even that is not as simple as xx xy, as sex is assigned at birth. Factors that are biological in nature change over time and are not stable as many believe. So endocrinologists and geneticists could not say definitively what is male, female, neither, or anything in between from a biological perspective due to this changing nature.

As a socially constructed concept, gender has magnified the perceived differences between females and males leading to limitations of attitudes, roles, and how social institutions are organized. For example, gender norms influence the jobs viewed as appropriate or inappropriate for women or men, and household or parenting responsibilities are divided between men and women.

Gender is not just a demographic category. It also influences behavioral norms, the distribution of power and resources, access to opportunities, and other important processes (Bond, 1999). For those who live outside of these binary traditional expectations for gender, the experience can be challenging. The binary categories for sex, gender, and gender identity have received the most attention from both society and the research community, with the most attention given to gender identities most recently (e.g., gender-neutral, transgender, nonbinary, and GenderQueer) in recent years (Kosciw, Palmer, & Kull, 2015).

The attention paid to other gender identities and to changing gender identities is increasing, both academically and publicly. As a teenager, Nicole Maines, a successful actor who portrayed television’s first transgender superhero in Supergirl, filed an anonymous lawsuit after being excluded from the school restroom because of her transgender identity. The suit resulted in a victory before the Maine Supreme Judicial Court in 2014. This was the first state court to rule that barring transgender students from the school bathroom that matches their gender identity is unlawful (Maines, 2015; Nutt, 2015).

Gender is not a new complex conversation for many communities, but in the United States it has become about laws and who has the right to determine what gender is and when children are old enough to understand how they experience it. As of the time of this writing, there are more than 400 pieces of anti-trans legislation in the United States.

Sexuality

Sexuality refers to a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, physical, and spiritual attractions toward another in relation to their own sex or gender. Sexuality exists on a continuum or on multiple continuums, and it crosses all dimensions of diversity (e.g., race, ethnicity, social class, ability, religion, etc.).

Sexuality is different from sex, gender identity, or gender expression. Over time, gay, lesbian, asexual, and bisexual identities have extended to other sexualities, such as pansexual, polysexual, and fluid. Increasingly, research is being conducted on these populations (Kosciw et al., 2015). Members of the LGBTQIA2S+ communities have been historically marginalized and oppressed, facing both legal restrictions and social stigma. One step forward was the legalization of same-sex marriage in the United States.

Not all communities have the same social constructs regarding gender and sexuality. As a provider, be careful not to assume that the sexual constructs used in your own community are the same as those of clients you will be working with.

Age

Age describes the developmental changes and transitions that come with being a child, adolescent, or adult. Power dynamics, relationships, physical and psychological health concerns, community participation, and life satisfaction vary for individual members of different age groups (Cheng & Heller, 2009).

Age stereotypes contribute to ageism and adultism. Ageism refers to the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel), and discrimination (how we act) toward others or oneself based on age. Stereotypes that characterize older people as slow, frail, incapable, out-of-touch, or grumpy are harmful.

Although the skills, values, and training of human services professionals can make a difference in the lives of older adults, the attitudes within our profession and society are barriers. Seeing both older adults and young children as capable is key to being strengths-based in your approach to working with them. However, we must be careful not to dismiss the need to learn to evolve with the times and not assume that just because “they have always been done this way,” traditions, ways of practicing, and ways of thinking, including elders’ views of how youth and children can involved in society and make their own decisions, must stay the same.

Youth activism and voices are also part of what we need to consider. Assuming that correct answers are only going to come from someone who is older does a disservice to children and youth whose voices come with knowledge and truth in younger bodies.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a way of describing an individual’s or family’s status that includes three components: education, income, and employment. The education component refers to the highest level of education completed: high school, a certificate, training programs (CTE), college, or advanced degrees. Income includes not just wages, but also sources such as stocks, bonds, or real estate, as well as inherited wealth. Employment refers to the level of status that one’s job or career has within society. Employment status may or may not be equivalent to level of education or salary.

Socioeconomic status is a complex combination of factors that indicates difference in power, privilege, economic opportunities, and resources. It will also relate to a person’s social capital, which is the relationships and networks that each person has available to them. For example, the college professor might be more likely to be able to connect one of their children or friends to a job with a researcher, whereas the doctor might be able to connect an ill family member with a colleague who is an expert in medical specialty.

Socioeconomic status and culture shape a person’s worldview. It influences how they feel, act, and fit in. It also impacts the schools they attend, the health care they have access to, and the jobs they have throughout life. The differences in norms, values, and practices between social classes can also have impacts on parenting, well-being, and health outcomes (Cohen, 2009).

Ability and Disability

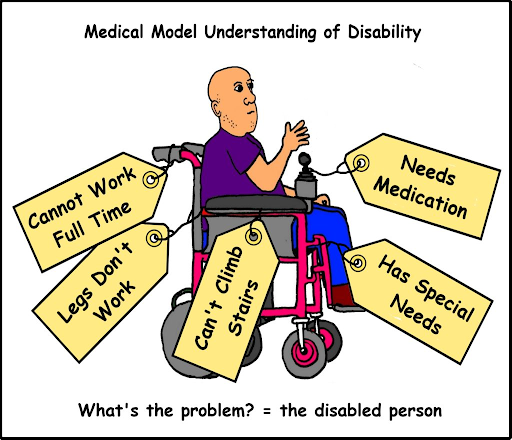

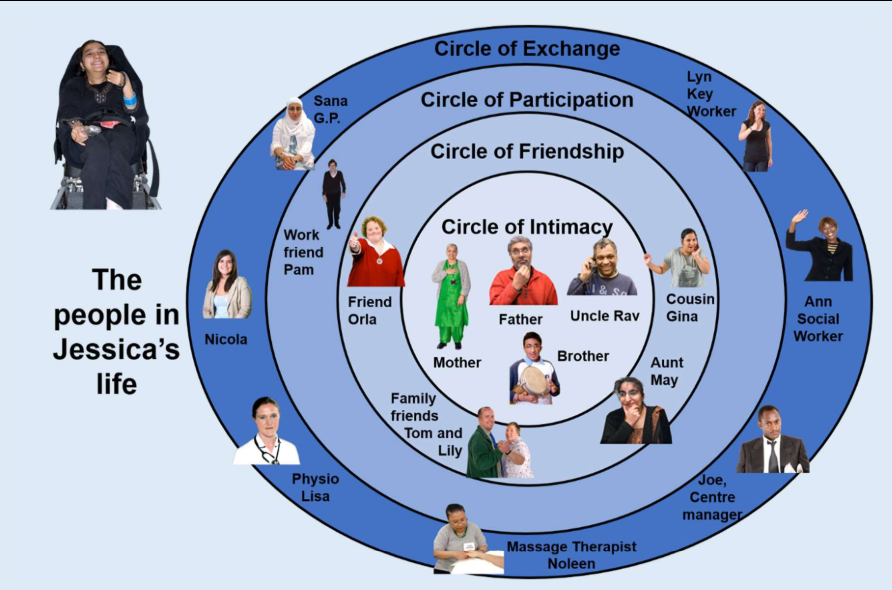

Disabilities refer to visible or hidden and temporary or permanent conditions that provide barriers or challenges. They can impact individuals of every age and social group. In the past disability was viewed using a medical model, primarily by explaining diagnosis and treatment models from a pathological perspective (Goodley & Lawthom, 2010). In this traditional approach, depicted in figure 2.5, individuals diagnosed with a disability are often discussed as objects of study instead of complex individuals impacted by their environment.

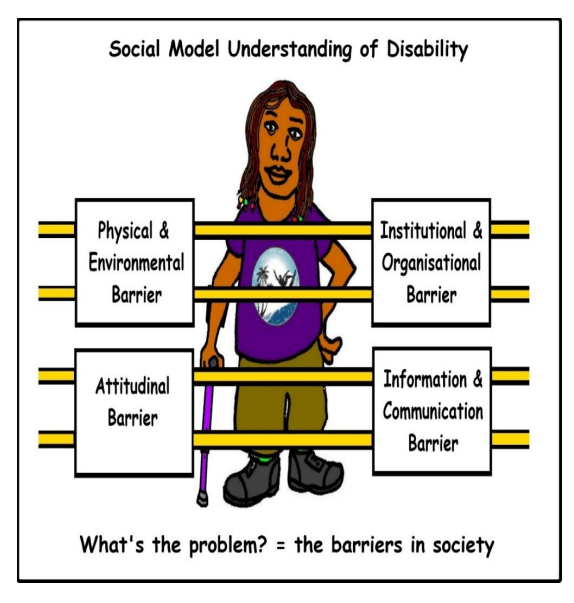

The more current social model views ability and diagnosis from a social and environmental perspective and considers multiple ecological levels. The experiences of individuals are strongly valued in this model. Community-based participatory research is a valuable way to explore experiences while empowering members of a community with varying levels of ability and disability.

Identifying who has a disability or health condition can be a challenge and can have real, tangible consequences for an affected person or group. For example, if prevalent research suggests that a particular disability or health condition is relatively rare, it is possible that few federal and state resources will be devoted to those individuals. But if the methodology for identifying individuals with that condition is flawed, then the prevalence rates will be inaccurate and potentially biased.

As human service providers, we must always consider how our own communities and the communities we work with understand and have access to support. How does this all impact children and youth under the age of 18 in schools and what happens after they leave the education systems? What do transitions to life after graduation look like if students and families receive support for that to happen for them?

Religion and Spirituality

Definitions of religion typically include shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity. Religion emphasizes beliefs and practices, relationships with the divine, and faith, all of which differentiate it from common definitions of culture. Further, religion is an important predictor for well-being, satisfaction, and other life outcomes (Tarakeshwar, Stanton, & Pargament, 2003). It involves an institutionalized system of religious attitudes, beliefs, and practices, plus the service and worship of God or the supernatural.

A differentiation between religion and spirituality has become more relevant recently, as many individuals consider themselves more spiritual than they are religious. Definitions of spirituality typically focus on a connection to something larger than yourself (a higher power), a quest for meaning, and a commitment to live each day in a sacred manner (Brady, 2020). Spirituality refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose. It is also the way people experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.

The importance of religion and spirituality to physical and emotional well-being and a strong sense of community merits the inclusion of both in research and practice (Tarakeshwar et al., 2003). Collaboration with religious organizations and embedding interventions into these settings may have positive impacts on individuals in the community and may also help religious organizations reach goals. However, if religious organizations exclude or condemn people based on other social characteristics (e.g. race, sexuality, or gender), then this could present a conflict for human services professionals who are committed to equity in service.

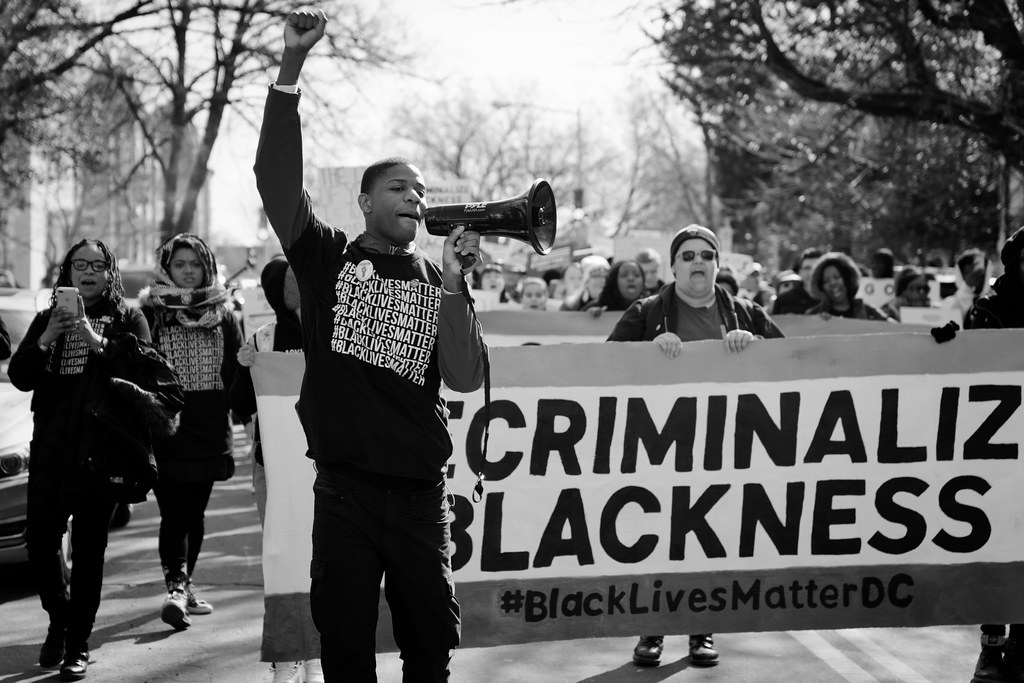

Privilege and the Dimensions of Diversity

Privilege, or the unearned advantages that individuals have based on membership in a dominant group (e.g., race, gender, social class, sexuality, ability), contributes to the systems of oppression for non-privileged individuals and groups. Privilege can come in multiple forms and individuals can have multiple privileges. In particular, White privilege, or the advantages that White people have in society, are important for psychologists to examine more extensively to understand how White people participate in systems of oppression for racial minority groups in the United States (Todd et al., 2014). As discussed earlier in this chapter, Black and Indigenous people have been actively oppressed. Activism, such as that pictured in figure 2.8, is one way that awareness has been increased.

White experiences and perspectives tend to be pervasive in curriculum, policy, pedagogy, and practices to the exclusion of work and research by people of color (Suyemoto & Fox Tree, 2006). This results in systems of privilege and oppression in society.

While the various dimensions of diversity discussed in the previous sections are a start for understanding human diversity, they do not fully describe an individual, community, or population. We, as human services professionals, must consider that these dimensions do not exist independently of each other. The following sections will explore how social constructivism, intersectionality, and the practice of cultural humility inform our understanding of the dimensions of diversity.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Diversity and the Human Services Profession,” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Dimensions of Diversity” by Nghi D. Thai and Ashlee Lien in Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change, Rebus Community. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: addition of “Origin and First Language”; updated language throughout; contextualized for human services; edited for clarity and relevance; additional and updated images.

Figure 2.3. “Census 2010: Ethnicity vs. Race” by Nathan Gibbs is licensed under CC BY NC SA 2.0.

Figure 2.4. “The Gender Unicorn” by Elan Paulson is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Figure 2.7. “The people in Jessica’s life” by HSE Ireland is shared under public domain.

Figure 2.8. “Black Lives Matter DC, March For Our Lives, Washington DC” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 2.5. “Medical Model Understanding of Disability” by Dave Lupton is all rights reserved.

Figure 2.6. “Social Model Understanding of Disability” by Dave Lupton is all rights reserved.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

well-being

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

process through which we learn the culture of the social groups that we belong to.

shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, physical, and spiritual attractions toward another in relation to their own sex or gender.Sexuality exists on a continuum or multiple continuums

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group

refers to the geographical location that a person was born and spent (at least) their early years in

the language an individual learns in early childhood

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes, primary, and secondary reproductive organs.

a set of fixed beliefs about a specific age group, usually referring to negative beliefs about older adults.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.

connection to something larger than you (a higher power), a quest for meaning, and a commitment to live each day in a sacred manner

the act of working with others.

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

a theory that emphasizes the shared understandings agreed to by members of a society.

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities