2.5 Social Construction of Difference

The dimensions of diversity can also be thought of as the various social identities we have. They can help us understand the social construction of difference, which is when hierarchical value is assigned to perceived differences between socially constructed ideas.

In forming our own social identities, we connect most easily to people who share the same group membership(s) that we do. According to the Social Identity Theory formulated by Henri Tajfel, we see people who are members of different groups as “others” (McLeod, 2019). Generally, we tend to be drawn to others who are more similar to ourselves, whether in appearance or in other social characteristics, such as age, ability, or sex. This, combined with the likelihood of overestimating the similarities and differences between groups, contributes to the social construction of difference.

Social Construction of Race

The social construction of race deserves special mention, since there is a broadly held public assumption that there are significant biological and genetic differences between human beings based on “race” (meaning observable physical differences such as skin color). In actuality, race is a social construct rather than a biological reality (figure 2.9).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CVxAlmAPHec

Watch this video from PBS Origins, entitled “The Origin of Race in the USA.” In this brief overview, you will learn the history of how we came to socially construct the categories of race and where they leave us today.

Reflecting on what you learned, consider the following questions:

- Where did the term Caucasian come from, and why do we still use it?

- How has race been used in both positive and negative contexts throughout history?

- What are some other points in history during which our understanding of race evolved?

Scientists state that while genetic diversity exists, it does not divide along the racial lines that many humans notice (Gannon, 2016). In fact, members of the human “race” (that is, all humans) share 99.9% of their genes (National Human Genome Research Institute, 2011). Ancestry and geography likely influence which genes get turned on and expressed. What complicates our understanding of race is that we have behaved for centuries as if there is a biological difference. Because there has been a longstanding discriminatory practice against people of color, there are multiple impacts today (Berger & Luckman, 1966).

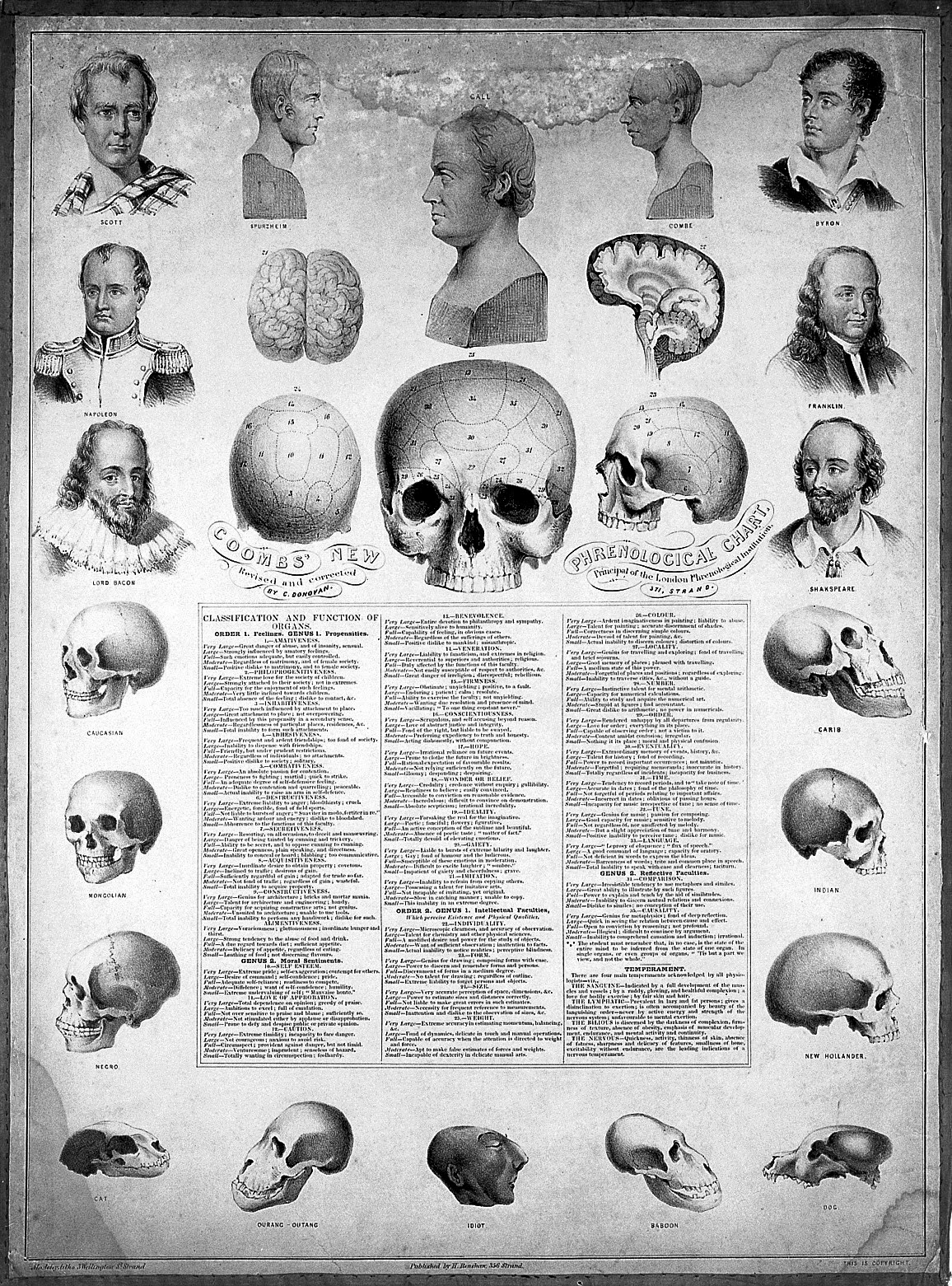

The reasons for doubting the biological basis for racial categories suggest that race is more of a social category than a biological one. Another way to say this is that race is a social construct. In this view, race has no real existence other than what and how people think of it, as shown by variations in skull shape in figure 2.10.

This understanding of race is reflected in the problems of placing people with multiracial backgrounds into any one racial category. Would you consider former President Barack Obama to be White, Black, or multiracial? He had one Black parent and one White parent. As another example, the well-known golfer Tiger Woods was typically called an African American by the news media when he burst onto the golfing scene in the late 1990s. In fact, his ancestry is one-half Asian (divided evenly between Chinese and Thai), one-quarter White, one-eighth Native American, and only one-eighth African American (Williams-León & Nakashima, 2001).

Historical examples of attempts to place people in racial categories further underscore the social constructionism of race. In the South during the time of slavery, the skin tone of enslaved people lightened over the years as babies were born from the union, often in the form of rape, of slave owners and other Whites with enslaved people. As it became difficult to tell who was “Black” and who was not, many court battles over people’s racial identity occurred. People who were accused of having Black ancestry would go to court to prove they were White in order to avoid enslavement or other difficulties (Staples, 1998).

Litigation over race continued long past the days of slavery. In a relatively recent example, Susie Guillory Phipps sued the Louisiana Bureau of Vital Statistics in the early 1980s to change her official race to White. Phipps was descended from a slave owner and an enslaved person and thereafter had only White ancestors. Despite this fact, she was called “Black” on her birth certificate because of a state law, echoing the “one-drop rule,” that designated people as Black if their ancestry was at least 1/32 Black (meaning one of their great-great-great grandparents was Black). Phipps had always thought of herself as White and was surprised after seeing a copy of her birth certificate to discover she was officially Black because she had one Black ancestor about 150 years earlier. She lost her case, and the U.S. Supreme Court later refused to review it (Omi & Winant, 2015).

Social Construction of Other Identities

Social construction of gender is another widely accepted concept in human services. The differences that we attribute to the biological designation of female, male, or intersex are predominantly constructed by our societal beliefs and not by biology. The recent broadening of gender identity and expression clearly demonstrates this concept.

Other identities are also constructed via societal agreement. Sexuality, ability, religion, ethnicity, age, and other identities may contain some physical parameters and certainly contain meaning to the individuals that possess them. However, critical to our study of families is the understanding that society creates and reinforces social construction of these characteristics and those constructions favor some groups, discriminate against others, and generally impact the lives of families.

Intersectionality

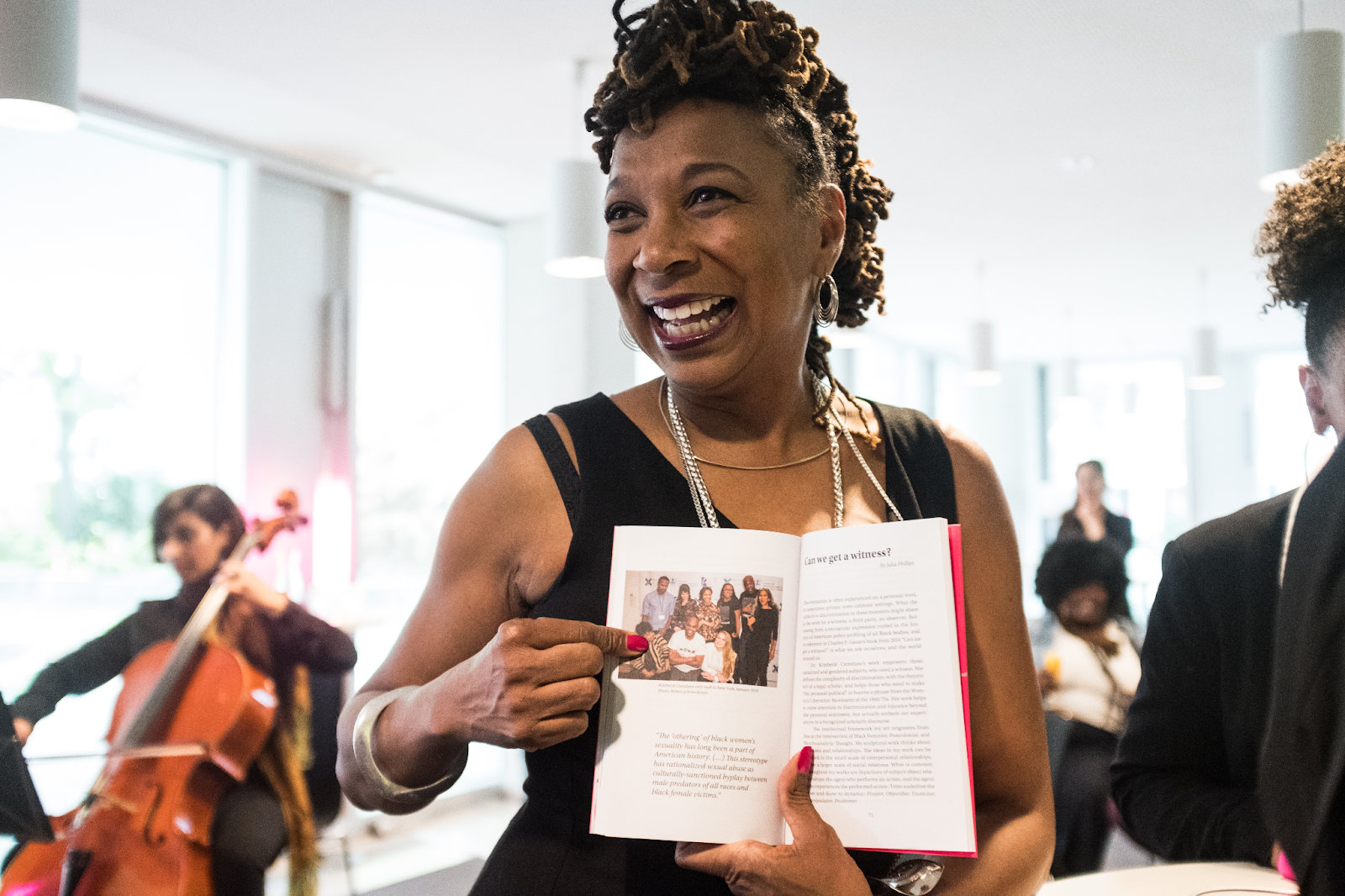

Articulated by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991), the concept of intersectionality identifies the ways that race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously. This means that multiple inequalities affect the life course of any individual.

Notions of gender and the way a person’s gender is interpreted by others are always impacted by notions of race and the way that person’s race is interpreted. A person is never received as only a woman—how that person is racialized impacts how the person is received as a woman. While a White woman may experience some bias or discrimination based on gender, a woman who is Black may experience discrimination based on both race and gender. So, notions of Blackness, Brownness, and Whiteness always influence gendered experience, and there is no experience of gender that is outside of an experience of race.

In addition to race, gendered experience is also shaped by age, sexuality, class, and ability. Likewise, the experience of race is impacted by gender, age, class, sexuality, and ability.

Understanding intersectionality requires a particular way of thinking. It is different from the ways in which many people imagine identities operate. An intersectional analysis of identity is distinct from single-determinant identity models, which presume that one aspect of identity (say, gender) dictates one’s access to or disenfranchisement from power.

An example of this idea is the concept of global sisterhood, which is the idea that all women across the globe share some basic common political interests, concerns, and needs. If women in different locations did share common interests, it would make sense for them to unite on the basis of gender to fight for social changes on a global scale. However, if the analysis of social problems stops at gender, we miss an opportunity to pay attention to how various cultural contexts shaped by race, religion, and access to resources may actually place some women’s needs at cross-purposes to other women’s needs. Therefore, this approach obscures that women in different social and geographic locations face different problems.

Although many White, middle-class women activists of the mid-twentieth century United States fought for freedom to work and legal parity with men, this was not the major problem for women of color or working-class White women, who had already been actively participating in the US labor market as domestic workers, factory workers, and enslaved laborers since early colonial settlement. Campaigns for women’s equal legal rights and access to the labor market at the international level are shaped by the experiences and concerns of White American women. In contrast, women of the Global South, in particular, may have more pressing concerns: access to clean water, access to adequate health care, and safety from the physical and psychological harms of living in tyrannical, war-torn, or economically impoverished nations.

An intersectional perspective examines how identities are related in our own experiences and how the social structures of race, class, gender, sexuality, age, and ability intersect for everyone. For example, “gender” is too often used simply and erroneously to mean “White women,” while “race” too often connotes “Black men.” As opposed to single-determinant and additive models of identity, an intersectional approach develops a more sophisticated understanding of the world and how individuals in differently situated social groups experience differential access to both material and symbolic resources, such as privilege.

Cultural Humility and Cultural Competence

As our world becomes increasingly diverse and interconnected, understanding each others’ experiences and cultures becomes crucial. Without a basic understanding of the beliefs and experiences of individuals, professionals can unintentionally contribute to prejudice and discrimination or negatively impact professional relationships and the effectiveness of services. To understand cultural experiences, it is important to consider the context of social identity, history, and individual and community experiences with prejudice and discrimination. It is also important to acknowledge that our understanding of cultural differences evolves through an ongoing learning process (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Cultural competence is generally defined as possessing the skills and knowledge of a culture to work with individual members of the culture effectively. This definition includes an appreciation of cultural differences and the ability to work with individuals effectively. However, the assumption that any individual can gain enough knowledge or competence to understand the experiences of members of any culture is problematic. Gaining expertise in cultural competence, as traditionally defined, seems unattainable, as it involves the need for knowledge and mastery. True cultural competence requires engaging in an ongoing process of learning about the experiences of other cultures (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

Cultural humility, which takes into account this ongoing process, is the current model for human services professionals. Cultural humility is the ability to remain open to learning about other cultures while acknowledging one’s own lack of competence and recognizing power dynamics that impact the relationship. The practice of cultural humility requires continuous self-reflection, recognition of the impact of power dynamics on individuals and communities, embracing “not knowing,” and a commitment to lifelong learning. This approach to diversity encourages a curious spirit and the ability to openly engage with others in the process of learning about a different culture. As a result, it is important to address power imbalances and develop meaningful relationships with community members in order to create positive change (Culturally Connected, n.d.).

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Social Construction of Race” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “The Meaning of Race and Ethnicity” in Sociology: Understanding and Changing the Social World by Anonymous. License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: rewritten for clarity.

“Intersectionality” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Intersectionality” in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, and Laura Heston, UMass Amherst Libraries. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: rewritten for brevity, reading level, and human services context. New images added.

“Cultural Humility” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is adapted from “Cultural Humility” by Nghi D. Thai and Ashlee Lien in Introduction to Community Psychology: Becoming an Agent of Change, Rebus Community. License: CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: updated language; contextualized for human services; edited for clarity and relevance.

Figure 2.10. “Phrenological chart with portraits of historical figures and illustrations of skulls exhibiting racial characteristics” Lithograph by G. E. Madeley, authored by C. Donovan is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 2.11. “Kimberlé Crenshaw” by Heinrich-Boll-Stiftung is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 2.9. “What is the Origin of Race in the United States” by PBS Origins is licensed under a YouTube Standard license.

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes, primary, and secondary reproductive organs.

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

refers to the geographical location that a person was born and spent (at least) their early years in

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, physical, and spiritual attractions toward another in relation to their own sex or gender.Sexuality exists on a continuum or multiple continuums

shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity

social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation