4.2 Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals

As you consider entering the profession of human services, it is important to think about the role you will play as well as the responsibilities that come with that role. One of the joys and challenges of working with human beings is that unique interactions occur every day. Whether you are a director, a supervisor, a receptionist, an assistant, or a case manager, you will encounter situations that you have not seen before. The field of human services was developed in response to human needs and human problems. It is a profession dedicated to helping diverse individuals solve the challenges they face while valuing each person’s community, culture, and self-determination. While doing so, the professional must act with integrity and compassion, and with social justice in mind.

There is no set of directions to follow when you work with individuals. When putting together a piece of furniture or baking cookies, for instance, you might follow instructions or recipes. You might even deviate a little bit or add your own flair to the project. Working with individuals and families, however, requires a stronger internal set of values and principles. That foundation is one that you build inside yourself using the tools of education, experience, and an understanding of ethics, which are the moral principles of the profession. To make ethical decisions, we must be aware of the biases and pressures that influence our thinking. We must also be aware of the intersection of the systems of privilege that shape the lens we use to see the world around us and how we use the information and influence we have.

Codes of ethics for the human services profession will help you build your professional foundation. In fact, you will be required to use that code as soon as you start working, including during your practicum and internship experiences.

All professions have a code of ethics, and those codes have many similarities in terms of how they relate to being responsible toward clients, colleagues, and society. For example, psychologists, attorneys, medical professionals, and social workers all embed these obligations and duties within their ethical codes. In this chapter, we focus on the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals from the National Organization for Human Services (Figure 4.1).

Any code of ethics is also embedded within the cultural norms of the local community, the country, and the ethos of the world. As we examine ethics, we must also look at values and culture. It is important to note that different countries and cultures have differing values and that subcultures within the United States may conflict with, complement, and/or mirror the country’s overall norms.

It is critical to pay attention to the cultures and values of the families that you work with, as well as being mindful of your own ethics and values. Looking at all of these elements together is complicated, which is why ethics are being highlighted as you start learning about this profession. It takes time, experience, education, and reflection to develop your foundation. This chapter will support that building process.

Structure of NOHS Ethical Standards: Two Sections

The National Organization for Human Services (NOHS) is the professional organization that serves both students and working professionals. As a member of this organization, practitioners network, follow research, and support one another. The NOHS ethical standards consist of two sections:

- Preamble: a short narrative introduction to the overall profession and reason for codes.

- Ethical standards: forty-four standards grouped into seven categories— responsibility to clients, colleagues, profession, public and society, employers, self, and students.

The most recent set of ethical standards adopted by NOHS in 2024 begins with a preamble that outlines the importance of each professional’s behavior and the fundamental values of the human services profession.

Preamble

The preamble focuses on characteristics of the profession, such as helping others and paying attention to the context of individuals and families. It emphasizes the role of education and professional growth.

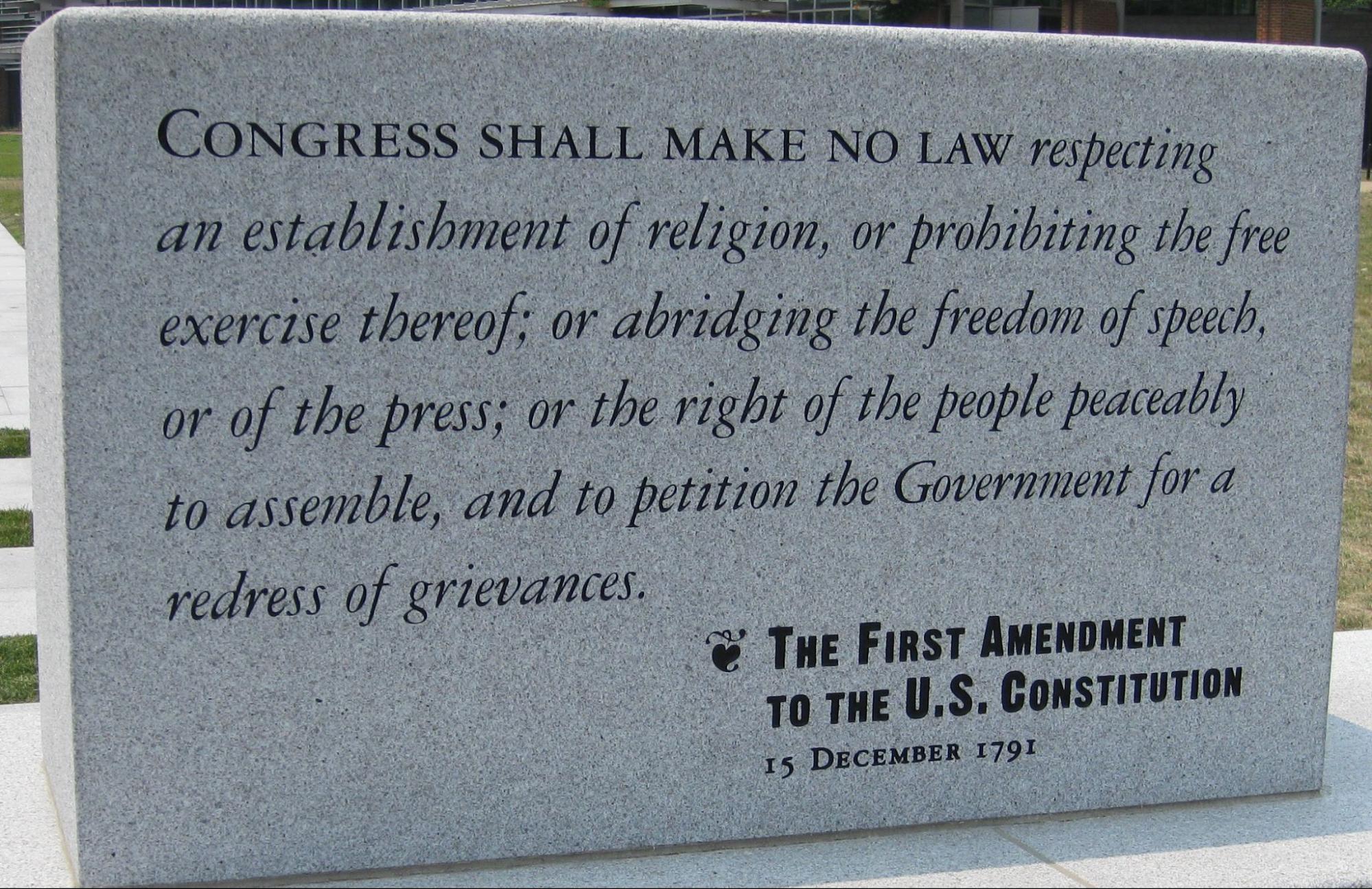

A key part of the preamble is the acknowledgment of conflicts that may exist between the code and other policies and expectations, such as employer policies, credentialing boards, laws, and personal beliefs, as indicated in figure 4.2. Each entity has some shared but some differing priorities, and this can lead to inconsistencies in what is best in any given situation. We will look at ethical dilemmas later on to help us understand this section of the preamble better.

The fundamental values of human services are described as follows:

- Respect the dignity and welfare of all people.

- Promote self-determination.

- Honor cultural diversity.

- Advocate for social justice.

- Act with integrity, honesty, genuineness, and objectivity.

The preamble reminds us that professionals as well as students and educators are bound by these standards.

Ethical Standards

This next part of the NOHS ethical standards includes a brief introduction and then summarizes the forty-four standards into a bullet list. We will introduce some of the core codes that, in our opinion, will most help guide your introduction into the human services profession.

Professional Responsibilities

The NOHS ethical standards assign standards to seven groups: clients, the public and society, colleagues, employers, the profession, self, and students.

Responsibility to Clients

Clients are the first and most obvious group to highlight. The very first standard describes the responsibility of recognizing and building on individual and community strengths. The prominence of this statement emphasizes its importance. Overall, these standards focus on the professional–client relationship and how to maintain standards during your interactions with the client. There are nine total standards:

- Be strengths-based.

- Obtain informed consent.

- Observe privacy and confidentiality.

- Protect from danger or harm.

- Avoid dual or multiple relationships.

- Prohibit sexual or romantic relationships.

- Ensure that personal values or biases are not imposed.

- Protect client records.

- Utilize technology in legal and confidential ways.

This set of standards contains concrete actions, such as preserving the privacy and confidentiality of clients, as well as more abstract concepts, such as maintaining a strengths-based approach. Which of these standards might be most challenging to implement? How are we making considerations for communities that have limited language or cultural resources that will require some dual or multiple relationships, like those in rural communities, Native communities, and communities that have small numbers of people that speak a language? How are we evolving to make our services more accessible for people with different abilities? How can we advocate expanding internet access to communities that, according to the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, 58 percent of the United States population does not have?

Responsibility to the Public and Society

Human services professionals are not always focused on a singular client, or discrete clients and families. Listed second in the NOHS ethical standards is the responsibility to see how greater society affects individual problems as a requirement of the profession.

Understanding social problems, which involve any condition or behavior that has negative consequences for large numbers of people and is generally recognized as a condition that needs to be addressed by society, helps the professional to avoid blaming the client for their personal troubles. Multiple factors contribute to the complexity of social problems. Typically the solution to the problem needs to be systemic in nature; in other words, it cannot be solved by any one individual. For example, both houselessness and racism are considered social problems. Human services professionals need to recognize the effects of the social problems on individuals, as well as to work toward solving those social problems systematically.

These nine standards remind us of the social justice mission of the profession:

- Provide services without discrimination or preference related to social characteristics.

- Be knowledgeable and respectful of diverse cultures and communities.

- Be aware of laws and advocate for needed change.

- Stay informed about current social problems.

- Be aware of social and political issues that differentially affect people.

- Provide ways to identify client needs and assets and advocate for needs.

- Advocate for social justice and to eliminate oppression.

- Accurately represent their credentials to the public.

- Describe treatment programs accurately.

Whether you work on the macro, mezzo, or micro level in human services, you must keep the macro—or societal—level in mind and work to decrease discrimination, disparities, and social problems. How are we using our social capital to bring voice to historically marginalized communities and center the experiences of those not in decision-making rooms?

Knowing the difference between having an interest in an area and having expertise in an area is essential. We must understand that we have to continue to learn and examine whether we are the best people to provide support or if we should uplift others within those communities to do so.

Responsibility to Colleagues

Being ethical in behavior toward colleagues is crucial to the healthy functioning of any agency, as well as across organizations. It’s especially important to work together so that funding is used effectively and services are coordinated but not duplicated by multiple agencies. These four standards speak to the value of having integrity with everyone you work with:

- Coordinate, collaborate, but do not duplicate services.

- Deal with conflict by approaching the person directly; follow up with a supervisor if needed.

- Respond to unethical behavior of colleagues.

- Keep consultations between colleagues private.

You might not have considered having ethical responsibilities to colleagues, but you do! Are you practicing nonviolent communication principles or other communication with colleagues, as indicated in figure 4.4? Are you willing to challenge your colleagues, who may also be your friends?

| Component | Communication |

|---|---|

| 1. Observation | “When this happened…” |

| 2. Feeling | “I’ve felt this way…” |

| 3. Need | “Because I have a need/hope/value…” |

| 4.Request | “Could you please…?” |

Responsibility to Employers

The responsibility to your employer supports your commitment to clients and to the public. These three standards emphasize this, with a particular focus on seeking resolution if you experience a conflict of interest at work:

- Stick with commitments made to employers.

- Create and maintain high-quality services.

- In conflicts between responsibility to employer and responsibility to clients, seek resolution with all involved.

We must consider how the intersectionality of our identities impacts what this looks like for all parties involved: the client, the provider, the public, and the employer. What systems of power interact, and who benefits from each of these interactions? What will sticking to the commitments we made to our employers cost us in comparison to what sticking to the commitments to our clients cost us? Understanding the costs is a conversation we must understand how to navigate.

Responsibility to the Profession

Being responsible to the profession includes the commitment to lifelong learning and growth. It also means acknowledging that both workers and the profession itself need to be nurtured in order to continue to develop.

- Gain education and experience to work effectively with culturally diverse individuals based on age, ethnicity, culture, race, ability, gender, language preference, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality, or other historically oppressed groups.

- Know your own limits; serve others within those limits. Scope of practice is generally a term applied to professionals. It’s essential when helping professionals/social workers/human service providers make a referral to a professional with knowledge, skills, abilities, and licensure/certification or the necessary training and experience to treat.

- Seek help when you need it. This does not only mean professional consultation from peers and supervisors. When we do not have the capacity to serve due to our personal resources being exhausted, we need external community and professional support.

- Promote cooperation among related disciplines. Transdisciplinary teams and interdisciplinary teams are good examples of what this could look like. Professionals who work in similar fields or fields adjacent to human resources—like early childhood, public health, education, occupational therapy, pharmacology, neurobiology, addictions, home visiting, community activism, conflict resolution, and restorative justice—are some of the fields are recommended to have a basic understanding of and make professional connections in to be able to not only have professional connections with but be able to do warm handoffs with when needed for referrals. We are all here to support and serve clients. We are just using different languages in our treatment plans. Let’s learn each other’s languages.

- Promote continuing development of the profession itself. This should be explored from different perspectives and sources outside the usual publishers. Consider looking at decolonized data authors, ethical data collection sources, more BIPOC and other diverse authors, open resources, and nonprofit and nonpartisan sources of information.

- Continue to learn and practice new techniques; inform clients appropriately. Use nonclinical language (also called plain language) when explaining what will happen in treatment to clients. Practice explaining text-heavy documents, such as informed consent and mandatory reporting requirements, to people of different ages, languages, and learning abilities. Can you explain that you are a mandatory reporter to a seventy-five-year-old monolingual English speaker as well as a seven-year-old for whom English is a second language? They both have the right to hear accurate information from you, and you have the ethical duty to explain this, or any new techniques, you may be using with them.

- Conduct research ethically. This is one of the most important ethical responsibilities that we have as a professional. Historically, helping professionals have caused irreparable damage to marginalized communities in the name of “science” and “helping advance” the field. Remember that there have ben hundreds of lives lost to unethical testing and non consensual testing done on Black and Brown bodies.

- Be thoughtful about self-disclosure, including on social media.

Being responsible toward your profession makes it more likely that everyone involved—agencies, professionals, and clients—will be successful.

Responsibility to Self

Being responsible to yourself is at the core of the ethical standards. The following three standards show that being self-aware of your emotions and health, as well as your own beliefs and biases, will make you a more effective and ethical human services worker:

- Develop awareness of your own culture, beliefs, biases, and values.

- Develop and maintain your own health.

- Commit to lifelong learning.

As a student, you know the challenges of balancing multiple responsibilities, including caring for yourself. While work life can be more focused than student life, prioritizing self-care is still challenging. Understanding the complex relationship with what health looks like for you includes the different domains of your life: spiritual, financial, mental, physical, emotional, friendship, familial, social, and environmental health. These form the umbrella of self-care in figure 4.5. Self-care is not a list of things to do, such as activities, but more about meeting your body’s needs for sleep, nutrition, and human connection. Your whole life purpose is not to produce and center only work. Learn how to integrate work into your life and the other way around.

Responsibility to Students

This is the only section of the standards that identifies a particular subset of human services professionals: the educators. Educators model the standards at the same time that they are teaching across the breadth of the profession. In particular the structure, quality, and adherence to the standards in the class setting, including field experiences, are the responsibilities of the educator. These eight standards emphasize the special duty that educators have to students who are in a relationship where power and status are unequal:

- Develop and implement culturally sensitive knowledge, awareness, and teaching methodologies.

- Commit to the principles of access and inclusion.

- Demonstrate high standards of scholarship.

- Recognize the contributions of students to the work of educators.

- Monitor field experience sites; ensure quality and safety.

- Establish guidelines for self-disclosure and opting out.

- Be aware of the power and status differential.

- Ensure students are aware of ethical standards.

Take a look at this set of standards from your position as the recipient of college faculty and internship supervisors’ good faith efforts to meet these standards. Can you see the value and importance of educators adhering to a code of ethics? How do you do this within a classroom setting? How do you weave conversations about ethics into all course content and conversations?

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

“Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 4.2. “First Amendment to the US Constitution” by elPadawan is licensed under CC-BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 4.3. “Protect Trans Kids” by Ted Eytan is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

Figure 4.4 is adapted from “Nonviolent communication” by Hannah du Plessis, licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Figure 4.5. “Self-Care” by Vatsla Adhikari is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 4.1. “NOHS Logo” is used under fair use.

a paid career that involves education, formal training and/or a formal qualification.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

viewpoints and efforts toward every person receiving and obtaining equal economic and social opportunities; removal of systemic barriers.

moral principles.

a credit class in which students apply theory to practice by using what you have learned in coursework in a real world setting with a supervisor/mentor who is invested in the student’s growth and development.

a credit class in which students apply theory to practice by using what you have learned in coursework in a real world setting with a supervisor/mentor who is invested in the student’s growth and development.

one of the distinguishing features of a profession, it sets standards and values for workers to uphold.

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

well-being

the practice of using the strengths of individuals, families, and communities to solve problems.

a problem affecting individuals that the affected individual, as well as other members of society, typically blame on the individual’s own personal and moral failings

(also known as “homeless”), when a person lacks a reliable place to sleep and care for themselves

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities

social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity

an alternative approach to criminal justice that centers the survivor, taking into account what they need to experience healing. It also involves the participation of the perpetrator, requiring them to recognize the harm they did in the process of holding them accountable.

action to preserve and improve one’s own physical and mental health.