4.3 Complexities of Ethical Behavior

Let’s dig a little deeper into some of the ethical standards and how they might lead to questions and dilemmas for practitioners. In this section, we will do the following:

- Focus on the ways that individual standards may support or conflict with one another.

- Contrast and compare common standards with national culture, policies, and practices.

- Focus on social justice.

- Draw attention to the importance of examining your own values more deeply and how those connect to the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals.

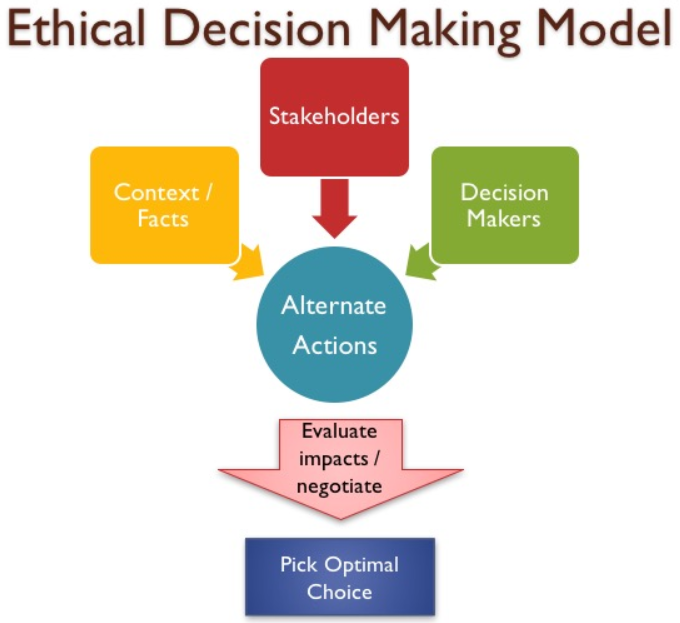

It is worthwhile to view the ethical standards in these multiple contexts, as in figure 4.6. Using and interpreting the ethical standards is a career-long process. Reminding ourselves that ethics is not something done when everyone is watching but when it is not always convenient and continual practice in the gray.

Privacy, Confidentiality, and Safety

Let’s start with something you may already be familiar with: privacy, confidentiality, and safety. While these may seem straightforward, there are other factors at play. Here are the full standards that describe these behaviors:

STANDARD 3: Human service professionals protect the client’s right to privacy and confidentiality except when such confidentiality would cause serious harm to the client or others, when agency guidelines state otherwise, or under other stated conditions (e.g., local, state, or federal laws). Human service professionals inform clients of the limits of confidentiality prior to the onset of the helping relationship.

STANDARD 4: When a human service professional suspects a client’s behavior may endanger themselves or others, they must take appropriate and professional actions to ensure safety, which may include consulting, seeking supervision, or, in accordance with state and federal laws, breaching confidentiality. (NOHS, 2024)

These two standards helpfully highlight the conflict between them in the last sentence of Standard 4, which states that it might include “breaking the confidentiality of the relationship.” Similarly, conflicting ethical standards appear in most codes for helping professions. Facing the dilemma of whether to break confidentiality in order to preserve someone’s safety is one that many human services professionals will confront during their careers. In those circumstances, the worker should take into consideration:

- Applicable laws and regulations of the region (e.g., when and to whom are reports made)

- Workplace policies

- The worker’s role (e.g., counselor, manager, student, receptionist)

- The Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals

- Any other resources and expectations

Notice that the professional’s own personal beliefs and values are not on this list. Nor are local or religious beliefs and values considered relevant to putting someone in danger. This relates to Standard 34 and the self-awareness that each professional is bound to keep regarding their own cultural backgrounds, values, and biases. What dilemmas might this pose for the professional?

Social Justice

Understanding that the systems of oppression and privilege have long-standing traumatic effects, as well as impacting clients’ health, well-being, and socioeconomic status, contributes to your ability to be an effective professional. These standards articulate the responsibility of human services professionals to be aware and to advocate.

STANDARD 14: Human service professionals are aware of social and political issues that differentially affect clients from diverse backgrounds.

STANDARD 16: Human service professionals advocate for social justice and seek to eliminate oppression. They raise awareness about systems of discrimination and inequity that affect historically minoritized and marginalized groups and advocate for systemic change to address these inequalities within their workplace, communities, and legislative systems. (NOHS, 2024)

Let’s look at a social issue, or social problem, currently affecting the United States and disproportionately affecting people who are in traditionally underrepresented ethnic groups. A social problem is typically defined as one that affects many people, affects the health and well-being of society, includes multiple causes and effects, and needs a systemic solution.

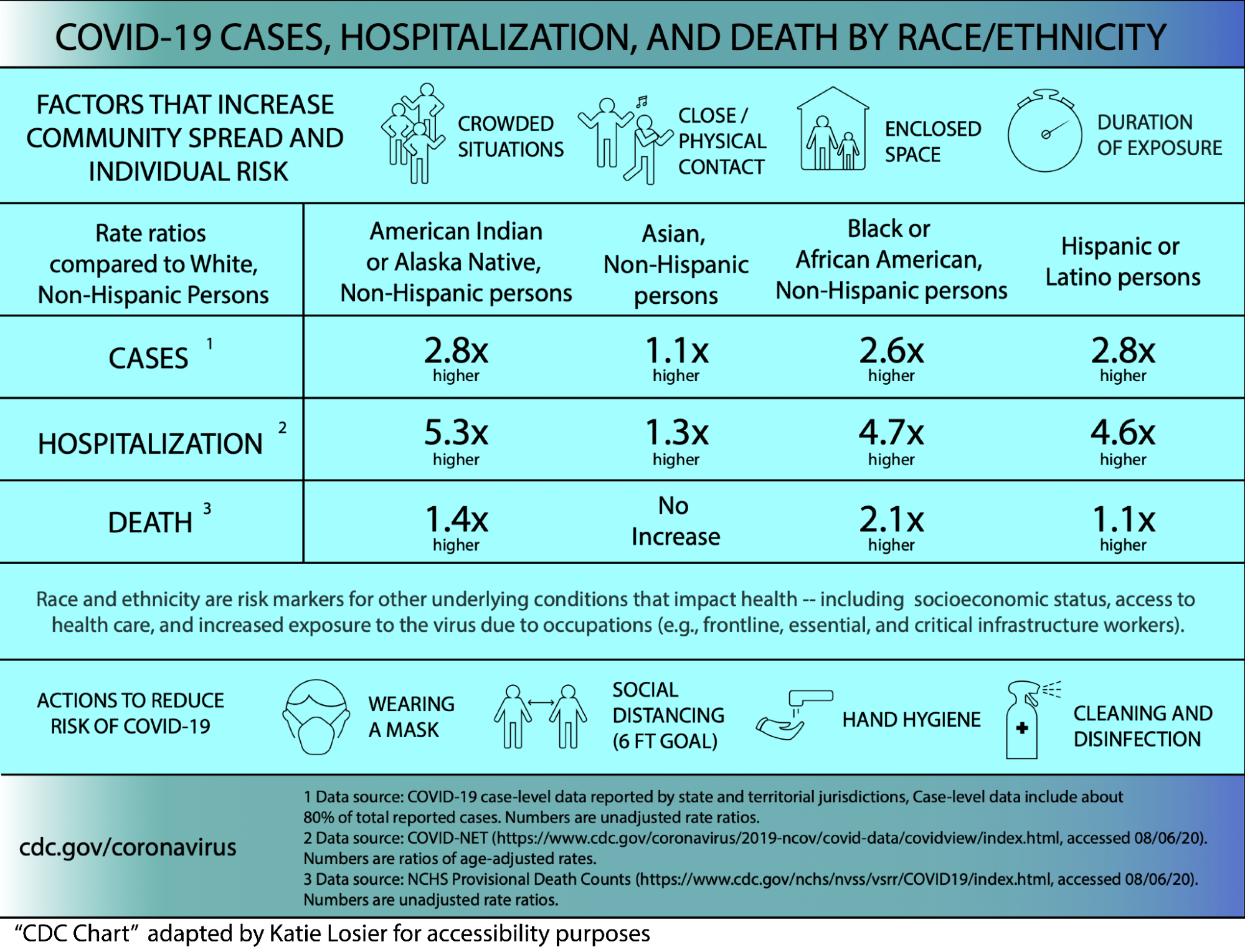

The COVID-19 pandemic is acknowledged to fit this definition. As a correlation, the disproportionate COVID-19 illness and death rate of people in ethnic minority groups could also be described as a social problem. In the United States (with data reported from 14 states), 33 percent of COVID-19 hospitalizations were among African Americans, although they made up 18 percent of the population in those states. With data from 51 states and territories, the reported death rates for Black, American Indian, and Alaska Natives was 1.4 times the death rates of White people. Latine people had a death rate that was 1.25 that of White people. Asians had the lowest death rate and were less likely than White people to die from COVID-19 (The Covid Tracking Project, 2021).

While we have the data to know that this is a social problem, how does this relate to the ethical standards? Relatedly, what contributes to underrepresented groups being more likely to get sick and also more likely to die if they are hospitalized for the illness?

The answers are complex, but here are some conclusions drawn from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, 2020) and other data. People from underrepresented groups are more likely to experience the following conditions:

- Live in densely populated areas and housing with fewer services such as medical clinics.

- Use public transportation more.

- Work in jobs that are essential and/or require exposure to the public such as transportation workers, store clerks, and factories supplying food or other essential products.

- Work in jobs that have few or no benefits such as sick leave or health insurance, meaning that they may be more likely to go work even if they or family members are sick.

Although we have not discussed COVID-19 and age here, this chart is provided for contextual reasons (figure 4.7).

Access to health care services and health care insurance is inequitable in the United States. In particular, states that have not expanded Medicaid funding as allowed under the Affordable Care Act have higher populations of ethnically underserved groups.

Whether this information is brand new to you or you are familiar with this data, it seems obvious that there are multiple social problems to be unraveled and examined. Poverty and low socioeconomic status intersect with the racial and ethnic inequities examined here. All of us have been affected by the pandemic. Some of us have personal experiences with illness and death related to the pandemic.

The question is, how does the human services professional adhere to ethical standards 14 and 16? Standard 14 talks about awareness. Just by reading this section of the textbook, your awareness has increased. What other steps could you take next to increase awareness? Standard 16 moves to another level, requiring the human services professional to advocate for social justice.

Advocacy takes many forms. Here are a few ideas:

- Educate yourself about information literacy. What are reliable sources of information? Help your clients understand how to understand information literacy in their own lives and how to ask questions of authority when they are unsure of their choices. Read and view those.

- Be aware of media bias and how it affects the information you consume. Evaluate media bias with questionnaires from organizations like the News Media Project, a nonpartisan education nonprofit that advances news literacy, is more engaged, is better informed, and empowers citizens. Look at this infographic on news media literacy [PDF] to improve your critical evaluation of news sources.

- Talk with people close to you. Share accurate information and inquire about why they have some long-held ideas that may be harmful. Are they open to hearing new information from you as their trusted source?

- Listen closely to people from underrepresented groups. Believe their experience. Stand by them. Bring stories that are not represented and use the systems of privilege that you are a part of to bring those forward in spaces where they are not normally heard.

- If you are from a historically and systemically underrepresented group and you feel comfortable and safe doing so, speak up and share your experiences. Your perspective is valid. Find people with whom you can build a community that shares similar identities to help you speak in spaces where you may be the only voices with your identities. Do so when ready to share your experience and not solely to educate others. This is an exhausting experience, and it can be dangerous, so know that you do not have to do this and that it is not your responsibility to do so. Your story is not the only story. (We), single stories, are not a monolith, so only do so if you have the time, energy, space, capacity, and community.

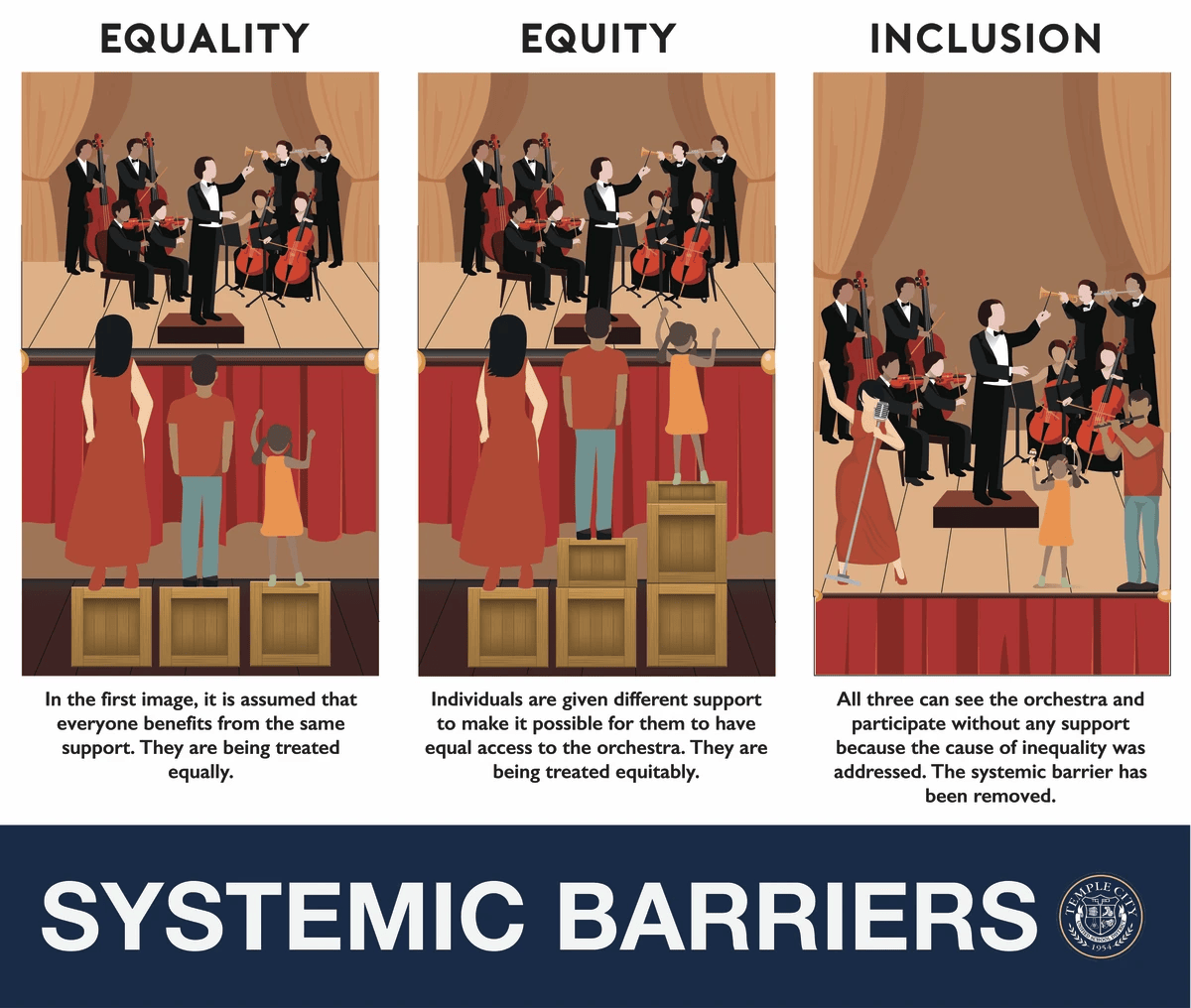

- Write a letter, send an email, call, or connect via social media to your political representatives and boards to change laws and policies that impact both how we practice ethically as human service providers and how all communities can have equal access to services. Remember, equality and equity are not the same thing. Do this through your local, state, agency, board, and national representatives and elections.

- Vote and help advocate for expanding and protecting voting rights for diverse groups. This includes stopping the movement to strip voter rights, the practices of gerrymandering and redlining, and using ID laws disguised as ways to restrict certain groups of people from accessing their right to vote.

- Take part in the U.S. Census and the American Community Survey. Help ensure that the census and other data-gathering instruments are valid and ethical. Consider diversity, how trauma impacts responses of the population, and how this information is kept anonymous and used. This also comes with a caveat that ethical data collection is critical. How do we store it? How long do we keep it? How do we keep it safe from parties that may want data in order to harm already vulnerable communities? How do we compensate people ethically for their time and information? How do we ask the right questions? Who is asking the questions? How is the data being collected? What are the right questions?

In the field of human services, there is an ethical responsibility to work toward a better society. The role a person plays in the workplace will define specific responsibilities and time allotment, but each professional will also have a commitment to the ethical standards and to working toward social justice.

Immersed in Values

Being aware of your own values is important self-knowledge, but it is even more critical to your work with clients. If you are not aware of your own values and beliefs, you may inadvertently make assumptions about others or project your own values onto clients.

STANDARD 34: Human service professionals maintain awareness of their own cultural and diverse backgrounds, beliefs, values, and biases. They recognize the potential impact of these factors on their relationships with others and commit to delivering culturally competent services to all clients. (NOHS, 2024)

Our personal values and beliefs come from multiple influences: our families, geography, the time we live in, and one or more cultures, which may include religion. They also come from the broadly held values, policies, and culture of the United States, which we will focus on here for a moment.

Author David Foster Wallace, in a 2005 commencement speech, used a metaphor for the ways in which we can be unaware of the social constructs that we live within:

There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?” (Wallace, 2009)

When we are immersed in something, we may not know exactly what it is. In the example above, the fish may not know to contrast water with other environments, like the earth or air. Living in the United States, we are grounded in ideas such as freedom, equality, and patriotism. But what do those words mean to you? And what do they mean in the context of the United States?

For example, the Declaration of Independence is commonly quoted to demonstrate that the United States is founded on equality: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

But as we know, this declaration did not apply to all men in the United States, only to men who were White, and in some cases was limited to land-owners. (Early in the history of the United States, individual states regulated the right to vote, so there was variability about which White men had access to equality, including voting.) Not to mention women were excluded at a time when the White culture defined sex and gender using a binary system.

Remember that equality is one of the central principles of democracy and is based on the belief that all people should have the same opportunities to be successful and have a productive, enjoyable life. Equality is rooted in fairness, since it is linked to meritocracy. The idea of equality is key to the notion that everyone will be able to achieve based on their efforts and contributions to society instead of their status or position.

Equity recognizes that not everyone begins in the same place in society. Some people face adverse conditions and circumstances that make it more challenging to achieve the same goals with the same effort. Equity advocates for those who may have been historically disadvantaged, which made it difficult for them to be successful.

Inclusion ensures equal access and opportunities for all people, regardless of their race, gender, disability, medical, or other needs. It eliminates discrimination and intolerance, and removes barriers that might prevent people from fully participating in society. Inclusive practices promote fairness, respect, and diversity, and recognize the value of everyone’s contributions.

Each professional needs to spend time thinking deeply about what their own values are and how they define those values. Examine the source of those values. If they come from the water that you are immersed in, it may be time to poke your head out to reexamine and redefine your perspectives and values.

Standard 34 is about awareness: deep knowledge about yourself and about how your culture, beliefs, biases, and values potentially interact with those of your clients and of society. This level of understanding does not come quickly or easily. While some of a person’s core beliefs and behaviors may be stable over time, most people grow, change, and deepen in their thinking and beliefs. Age, experience, education, and action all contribute to greater self-awareness. Action can come in the form of reflective thinking and writing, interaction with other thinkers and practitioners, and thoughtful listening and discussion.

As a student in the field of human services or the social work field, you are engaged in this process simply by reading, reflecting, and discussing ethical standards. You are expected to have some answers and be engaged in the process. One way that students can engage in this ongoing process is through clinical supervision in both group and individual settings. This space, visualized in figure 4.9, will explore the interactions and clashes of personal and professional ethics. It will challenge how ethical decision-making processes explore not just the ethical code but also how laws, values, and intersecting identities impact these processes using an organizational structure.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

Figure 4.7. “COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity” and “COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by age” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are in the public domain. Adaptation by Katie Losier licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Complexities of Ethical Behavior” is adapted from “Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 4.6. Ethical Decision Making Model by Shaun Taylor is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0.

Figure 4.8. “Systemic Barriers” by the Temple City Unified School District is in the public domain.

Figure 4.9. “Group talking” by RosZie is licensed under the Pixabay content license.

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

viewpoints and efforts toward every person receiving and obtaining equal economic and social opportunities; removal of systemic barriers.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

moral principles.

a situation in which one has to make a choice between two options that have competing values and are equally unfavorable.

any condition or behavior that has negative consequences for large numbers of people and that is generally recognized as a condition or behavior that needs to be addressed. Multiple factors contribute to the complexity of social problems. Typically the solution to the problem needs to be systemic in nature; in other words, it cannot be solved by any one individual.

develop strategies that fend off problems

the joint federal and state-sponsored program aimed at providing medical care to lower income individuals.

the state of lacking material and social resources needed to live a healthy life

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

shared systems of beliefs and values, symbols, feelings, actions, experiences, and a source of community unity

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes, primary, and secondary reproductive organs.

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.