6.2 Understanding Health Care Settings

Human services practitioners work with many clients who are also interacting with the health care system. Whether or not you are working in a health care setting, it is important to understand how health care and health insurance are organized in the United States.

In addition, workers must understand that physical and mental health are interrelated, although they have been socially constructed in the Western worldview as being separate, with mental disorders being stigmatized. Often mental illnesses, such as depression or anxiety, have been seen as something that a person should and could “get over,” as opposed to a physical ailment, such as a sprained ankle or strep throat, that merits medical attention and assistance.

Over time the Western worldview has become more understanding of the connections between physical and mental health, but the socially constructed difference still affects individuals and families. In this chapter, we will talk about both physical and mental health; chapter 6 will focus on mental health.

Models of Care

One of the debates over quality health care focuses on whether the health care system should aim to treat or prevent illness. This is known as the medical model versus wellness model of health care. In the medical model, providers address the needs of the consumer when problems are presented. This can be compared to fixing a machine when it breaks down. This reactive approach is dedicated to diagnosing and treating illness when a patient presents with a problem. This has been known as the Western medical model of care, which treats the symptoms but does not always look toward healing as the primary reason for interactions with clients. The wellness model, on the other hand, focuses on helping consumers maintain their health, on preventing illness, and on working with sick patients to make long-term improvements to their health, holistic care.

In 1978, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed moving away from the medical model to view health as a dynamic way of being instead of a specific goal to achieve (Ghebreyesus, 2020). Today, we use the wellness model of healthcare to better understand how daily habits and regular preventative care can add to the positive health of an individual. If you are a human services worker in a medical setting, you may be involved with helping to educate individuals or a community about the benefits of preventative care and to teach them how to get and stay healthy.

Health and Well-Being

Current longevity in the United States has been greatly impacted by advances in medicine. We have come a long way from the medieval practices of bloodletting and using bottled flatulence to ward off the Black Death. It seems that every day there is a new study, revolutionary drug, or innovative procedure that can improve outcomes for people of every age. Health care services, therefore, can still greatly improve someone’s quality of life, whether that person gets cured, their illness is managed, or they are made comfortable as they approach the end of their life.

However, Americans lag behind their counterparts in other countries when it comes to our health. Compared to our peers in 16 similar high-income nations, such as Japan, China, Britain, and Australia, the United States fares worse in several areas, including infant mortality, injuries and homicides, heart disease, and disability (Institute of Medicine of the National Academies, 2013). The same report identified inaccessible and unaffordable health care, poor diet and lifestyle choices, poverty, and convenience as factors in the disparity between the United States and similar countries.

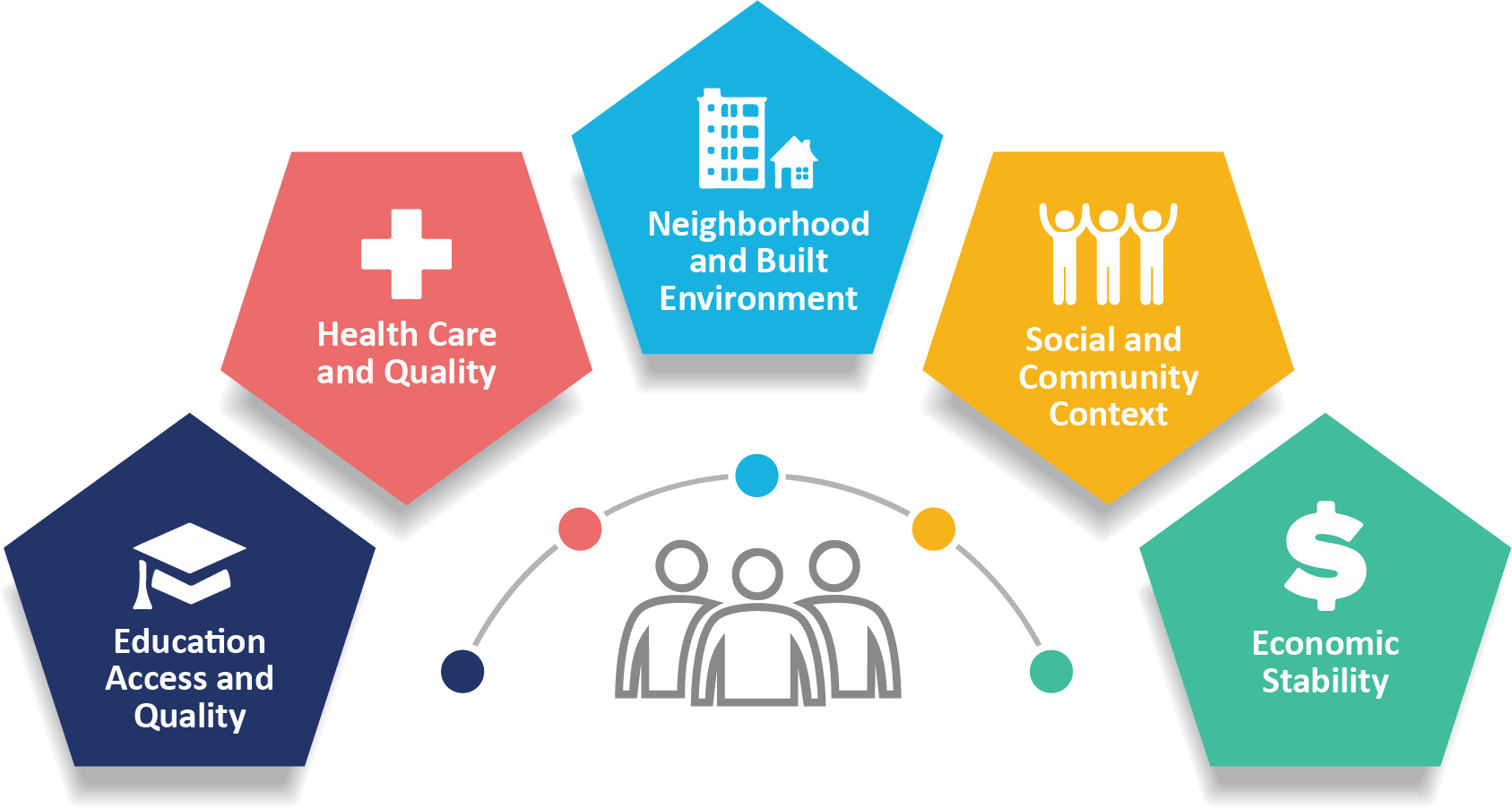

Differences in health status are not just the result of individual behavior but of social determinants of health (SDOH). These are preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations (CDC, 2008). Populations can be defined by factors such as race or ethnicity, gender, education or income, disability, geographic location (e.g., rural or urban), or sexual orientation. Health disparities are directly related to the historical and current unequal distribution of social, political, economic, and environmental resources.

Dimensions of Diversity and Health Disparities

The following text explores the significance and relevance of specific numbers in our work as human services providers. As we delve into the impact of social determinants of health on care models, we find that SDOH encompasses the various factors contributing to social disadvantages, which in turn lead to unequal access to care for specific populations. Race plays a significant role in determining access to care, ranging from basic medical insurance to dental services.

To be successful as human services providers, it is crucial to consider how our intersectional identities influence the analysis of the data we encounter. Our experiences, biases, and assumptions can affect how we interpret information. It is essential to recognize and challenge our biases to provide fair and equitable care to all individuals.

Moreover, we must consider how we address these disparities when navigating the care systems we work in. The lack of access to health care services can have truly devastating impacts on individuals and communities, underscoring the urgency of our work. It is our responsibility as human service providers to identify the root causes of these disparities, advocate for policy changes, and work toward creating a more equitable healthcare system for all.

By examining the significance of specific numbers and understanding the impact of social determinants of health, we can provide better care to those who need it most. This understanding also paves the way for us to work toward creating a fairer and more just healthcare system, a goal that should inspire and motivate us all.

Health disparities plague the United States as well. The environments in which people live, work, learn, and play affect family and individual health. Social determinants of health, such as social engagement, access to resources, safety, and security, are all impacted by the settings where families spend their time. Simply put, place matters when it comes to health. Health disparities result from multiple factors, including:

- Poverty

- Environmental threats

- Inadequate access to healthcare

- Individual and behavioral factors

Health disparities between Black and White Americans show a clear gap. In 2021, the average life expectancy for White adults was approximately six years longer than for Black adults: 76.4 compared to 70.8. An even more substantial disparity was found in 2008: the rate of infant mortality, which is the number of deaths in a given time or place, for Black infants was nearly twice that of White infants, at 10.4 compared to 4.4 per 1,000 live births (Hill et al., 2023).

Research has shown that individuals who identify as BIPOC are more likely to forgo medical care due to cost and lack of a personal healthcare provider compared to their White counterparts. According to recent data, a significant portion of Hispanic adults (34%), American Indian/Alaskan Native adults (24%), and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, Asian, and Black adults (21%, 19%, and 18%, respectively) do not have a usual doctor or provider (Hill et al., 2023). Furthermore, individuals from Hispanic (18%), American Indian/Alaskan Native (15%), Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander (14%), and Black (14%) communities are more likely to have missed a doctor’s appointment in the past year due to cost. Asian adults (7%) are less likely to do so. Additionally, Asian (33%) and Hispanic (36%) adults are more likely to have skipped a routine checkup in the past year compared to White adults (30%), while Black adults (21%) are less likely to have done so. Lastly, as of 2020, all BIPOC adults are more inclined than their White counterparts to have missed a visit to a dentist or dental clinic in the past year.

Studies have revealed that individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, American Indian/American Native, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander are more likely to experience food insecurity compared to their White counterparts (Hill et al., 2023). As of 2021, approximately 12% of Black adults and 8% of Hispanic adults faced low food security, which is significantly higher than the 4% of White adults who experienced this issue. Additionally, Black (13%) and Hispanic (11%) children were over twice as likely to experience food insecurity than White children (4%). However, no disaggregated data is available regarding American Indian/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander adults and children (KFF, 2021).

Furthermore, research has shown that individuals who identify as Black, Hispanic, American Indian/American Native, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander are more susceptible to being diagnosed with HIV or AIDS compared to their White counterparts (Hill et al., 2023). In 2020, the rate of HIV diagnosis for Black people was approximately seven times higher than the rate for White people, and the rate for Hispanic people was about four times higher than the rate for White people. Similarly, the rates of HIV diagnosis for American Indian/American Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander individuals were also higher than the rates for White people. The same pattern was observed in AIDS diagnoses, with Black people having a roughly nine times higher rate of AIDS diagnoses compared to White people, while Hispanic, American Indian/American Native, and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander people also had higher rates of AIDS diagnoses. Fortunately, the diagnosis rates for most groups have decreased since 2013. However, the HIV diagnosis rate has increased for American Indian/Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander individuals.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Original

“Understanding and Working in Health Care Settings” by Elizabeth B. Pearce is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Health and Well-being” adapted from Physical Health and Well-Being in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, is licensed under CC BY 4.0 and Health Equity by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Amy Huskey, Jessica N. Hampton, and Hannah Morelos in Contemporary Families 2e and licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: Minor editing for clarity; shortened; refocus of content on to human services.

“Models of Care” is adapted from “Treatment vs. Preventive Care” in Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World by Mick Cullen and Matthew Cullen, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adaptations by Elizabeth B. Pearce: minor editing for brevity and clarity; updated references.

Figure 6.1. “The five social determinants of health” by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

A physical, cognitive or emotional condition that limits or prevents a person from performing tasks of daily living, carrying out work or household responsibilities, or engaging in leisure and social activities.

the state of lacking material and social resources needed to live a healthy life

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

social identity based on the culture of origin, ancestry, or affiliation with a cultural group

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society