7.5 The Label, Not the Person

This section is an overview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and briefly describes some common diagnoses. As a human services worker, you may encounter individuals diagnosed with one or more disorders as well as individuals without a diagnosis. Having a fundamental understanding of these conditions is essential. However, it is crucial to remember that these clients should be prioritized as individuals over their diagnosis or any symptoms observed. While categorization serves to help us make sense of the world, it is essential to remember that when dealing with people, we must slow down and empathize with them, as they are not mere data points to be analyzed and categorized. They have personal histories, and our actions can significantly impact them. Therefore, prioritizing their humanity is necessary.

It is also essential to note that individuals not trained to diagnose should refrain from doing so. Still, basic knowledge of these disorders can help you navigate potential resources. Furthermore, the creation and influence behind diagnostic criteria should be considered.

The DSM is based on a Western medicine perspective of care, which can limit its perception of behavior, emotions, culture, sex, race, gender, social experiences of healing, what is considered medicine, and the providers who can provide advice. We must never forget that each person we encounter has a story and approach them with compassion and understanding. It is also necessary to consider that the DSM is imperfect and may not address every need of every person. Therefore, as human services workers, we must remain empathetic and open-minded.

The DSM has been referred to as the most important book of the twentieth century. Still, its imposing size disguises the intense uncertainty, factionalism, hostility, and political wrangling that has accompanied the development of each version of the DSM since its third edition in 1980. The first edition was first published in 1952 with 106 diagnoses; we now have over 300 conditions described in great detail, which only sometimes means more detailed diagnosis. The DSM has tried to consider language and cultural differences; however, it has yet to be as successful as it would like to believe it is.

Consider who participates in the workgroups for the DSM, which consists of more than ninety academic and mental health institutions worldwide. The selection of such a “diverse” group of professionals means that “many” viewpoints are being considered in each decision. Approximately 30 percent of individual participants in the workgroups are outside the United States. The following individuals were the committee members for the DSM 5 committee members. Nearly 100 are psychiatrists, 47 are psychologists, two are pediatric neurologists, and three are statisticians/epidemiologists. In addition, a pediatrician, speech and hearing specialist, social worker, psychiatric nurse, and consumer and family representative are also included. The were the members for the committee for the DSM-5.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA), as the leader of these task groups for the revision of the DSM, disclosed a conflict of interest with pharmaceutical companies. Still, in an “Honoria” way, a 2012 study showed that the members of the workgroups had not been entirely truthful with their financial disclosures by at least 20%, with as many of the workgroup participants having financially been complicated as shortly as a year before starting to partake in the workgroup and not disclose these connections? How can we not consider the close connection between pharmaceutical companies and the financial connection to many DSM diagnoses?

Something else to consider is that bilingual practitioners who must complete mental health assessments in Spanish are only trained in programs in the United States entirely taught 100 percent in English. It is difficult to find medical, especially psychiatric, diagnostic guides, let alone a DSM guide in Spanish that could be purchased locally (Portland, Oregon). In this case, some practitioners have to order from overseas from Spain, which can take multiple weeks and be incredibly costly. Not even a local medical school had a copy that could be bought from them, and even in Spanish, the diagnosis needed to be genuinely culturally sensitive. Just because something is translated into a language does not mean it is translated into a culture. This is just one language example; however, the DSM has been translated into 18 different languages, and nuance is essential, as is cultural context and knowledge.

Quick Reference Guide to DSM-5-TR Diagnoses

This feature was adapted from the DSM-5-TR. It is not intended to replace the use of the DSM in diagnosing a mental health disorder. It does not cover all of the diagnostic categories (e.g., eating disorders, sexual disorders, and others are omitted). Within each category, only a few of the more common diagnoses are listed, and summaries discuss common symptoms across diagnoses within a category. The guide also lists cultural considerations related to current and historical oppression as well as diversity in beliefs and assumptions about the world that impact evidence-based practice with clients with mental health disorders.

American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787

| Diagnostic category | Common symptoms | Most common diagnoses and their prevalence in the U.S. | Considerations for care across cultures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental disorders | – Specific or global limitations in social, intellectual, executive functioning & learning – Spectrum, or range of severity. – Manifest in early in life, often before school |

– Autism Spectrum Disorder: 1-2% of U.S children (Christensen et al., 2019; Maenner et al., 2020) – Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: 7.2% of U.S. children. (Thomas et al., 2015) – Intellectual Developmental Disorder: 1% of U.S. children. (Maulik et al.,2011) |

With similar symptom (a) White children are more likely to be diagnosed with neurodevelopmental disorders whereas Black & Latine students are more likely to be diagnosed with a conduct disorder (Mandell et al., 2007); (b) Men are more likely to be diagnosed than women (Rivet & Matson 2011). Foster-involved and justice-involved youth are more likely to develop these disorders (Ford et al., 2007; Lehmann et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2016) |

| Psychotic disorders | – Delusions (distorted thoughts) – Hallucinations (distorted sensations) – Disorganized thinking & speech – Disorganized or lack of movement – Diminished emotional expression, socialization, pleasure, or speec |

– Schizophrenia: 0.3-0.7% of the population (McGrath et al. 2008; Moreno-Küstner et al., 2018) – Substance-Induced Psychotic Disorder: 7% and 25% of individuals presenting with a first episode of psychosis (Crebbin et al., 2009) |

The content and meaning of delusions and hallucinations is informed by culture, which can make communicating about symptoms to people outside one’s identity groups.(Bauer et al., 2011; Larøi et al., 2014)Commonly held in other cultures and religious traditions may appear abnormal in our cultural context (Campbell et al., 2017; Olfson et al., 2002; Rassool 2015) |

| Bipolar disorders | Recurring episodes of depression and mania (type 1); or depression and hypomania (type 2)Mania is an excessively energetic, impulsive, euphoric, and grandiose state of mind. Hypomania is a less intense version that is less likely to occur with psychotic features. | – Bipolar I: 1.5% of U.S. adults (Blanco et al., 2017) – Bipolar II: 0.8% of U.S. adults (Merikangas et al., 2011) – Cyclothymic Disorder: 0.4-2.5% of children and adults, including European samples (Regeer et al., 2004; Van Meter et al., 2012) |

African-Americans with Bipolar I are more likely to be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia (Blanco et al., 2017; Gonzalez et al., 2010; Haeri et al., 011; Perlman et al., 2016)Countries with a reward-oriented culture have higher prevalence of bipolar disorder (Johnson & Johnson 2014)

For every one woman diagnosed with bipolar I, there are 1.1 men diagnosed with bipolar I. (Merikangas et al., 2011) |

| Anxiety disorders | – Excessive fear – Anticipation of future threats – Panic attacks – Usually develops in childhood – Phobias (like snakes, bridges) |

– Separation Anxiety Disorder: 4% of U.S. children (Cartwright-Hatton et al., 2006; Pine & Klein 2008) and 0.9%-1.9% of U.S. adults (Kessler et al., 2012; Shear et al., 2006; Silove et al., 2015) – Specific Phobia: 8-12% of U.S. population (Kessler et al., 2005; Kessler et al., 2012; Stinson et al., 2007; Wardenaar et al., 2017) – Generalized Anxiety Disorder: 0.9% of U.S. adolescents; 2.9% of U.S. adults; and 9% of U.S. population across their lifetime (Kessler et al., 2012) |

For many anxiety disorders, women are more likely to be diagnosed than men (e.g., LeBeau et al., 2010; Wardenaar et al., 2017).Cultures interpret anxious behaviors differently and have unique presentations of panic attack symptoms. (Lewis-Fernández et al., 2010)

Body-focused symptoms are more common in non-Western cultures. (Ruscio et al., 2017) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorders | – “Obsessions: recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or images that are experienced as intrusive and unwanted” – “Compulsions: repetitive behaviors or mental acts that an individual feels driven to perform in responseto an obsession or according to rules that must be applied rigidly.” (APA, 2022, para. 2) |

– Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: 1.2% of U.S. population (Kessler et al., 2005; Ruscio et al., 2010) – Body Dysmorphic Disorder: 2.4% of U.S. adults (Koran et al., 2008) – Excoriation disorder: 2.1% of U.S. adults in the past 12 months and 3.1% across their lifetime (Grant & Chamberlain, 2020) |

There are wide cultural variations in how clients express symptoms and how they make sense of their symptoms. Some clients attribute their symptoms to various physical, social, spiritual, and supernatural causes (Fernández de la Cruz et al., 2016; Grover et al., 2014; Pang et al., 2018).Body image concerns are impacted by culture. Clients are more concerned about eyelids in Japan (Hunt et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2010) and muscle dysmorphia in Western countries (Sreshta et al., 2017). |

| Trauma and stressor-related disorders | – Directly experiencing, witnessing, learning about traumatic events (not related to media consumption) – Recurrent dreams about the traumatic event – Flashbacks, memory lapses, persistent negative thoughts about the traumatic event – Emotional numbness, loneliness, sense of disbelief about loss or death |

– Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: 4.7% of U.S. adults in the past 12 months and 6.1-8.3% of U.S. adults across their lifespan (Goldstein et al., 2016; Kilpatrick et al., 2013) – Prolonged grief disorder: 9.8% of adults in any country (Lundorff et al., 2017) |

Women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with PTSD (Goldstein et al., 2016; Kilpatrick et al., 2013) partially due to greater likelihood of child abuse and interpersonal violence (Kessler et al., 1995)Somatic (body) symptoms are more common in non-Western cultures (Gupta 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2014)

Grief responses may manifest in culturally specific ways. For example, cultures vary in the expected duration of grief (Goldstein et al., 2018; Stelzer et al., 2020a; Stelzer et al., 2020b) and interpret the significance of nightmares in different ways (Hinton and Lewis-Fernández 2011; Hinton et al., 2013; Smid et al., 2018). Death rituals impact the spiritual status of the deceased in the eyes of clients, and the inability to perform them appropriately may prolong grief (Hinton et al., 2013). |

| Personality disorders | One’s thoughts, emotions, and behavior are very different from the norms and expectations in the broader culture.Same across a variety of personal and social situations

It affects all areas of a client’s life, beginning in adolescence |

– Any personality disorder (Cluster A, B, C): 10.5% of people have a personality disorder, including international samples (Huang et al., 2009; Morgan & Zimmerman, 2018) – Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder: Between 4.7% (Morgan and Zimmerman 2018) and 7.9% (Grant et al., 2004) of adults, including international samples – Borderline personality disorder: Between 2.7% (Morgan & Zimmerman, 2018) and 5.9% (Grant et al., 2008) of adults, including international samples |

Clients can appear to have symptoms that are actually adaptations to cultural barriers including: (1) rigid or dysfunctional behavioral patterns (Balaratnasingam & Janca, 2017; Fang et al., 2016; Ronningstam et al., 2018; Ryder et al., 2014), (2) guarded or defensive behaviors (Iacovino et al., 2014; Raza et al., 2014) (3) supernatural beliefs and practices outside of Western norms ((Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2018; Pulay et al., 2009) |

| Depressive disorders | “Sad, empty, or irritable mood.” (APA, 2022, para. 1) Lack of pleasure in previously fun tasks Disruptions in eating, sleep, movement, energy level, concentration. Suicidal ideation and feelings of worthlessness |

– Major depressive disorder: 7% of adults in the past 12 months (Kessler et al., 2003) | Major depressive disorder is three times as common in young adults (18-29 years old) than adults over 60 (Kessler et al., 2003) Women are two times more likely to develop depression (Salk et al., 2017) partially due to greater likelihood of child abuse and interpersonal violence across the lifespan (Altemus et al., 2014)Somatic (body) symptoms and other symptoms not in the DSM are more common in non-Western cultures (Kirmayer et al., 2017) |

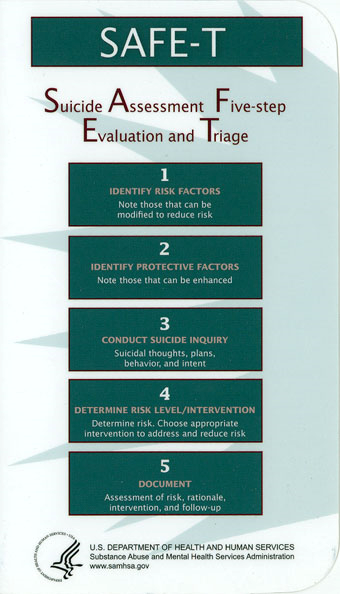

Suicide: We Need to Say the Word

The topic of suicide is a sensitive and challenging issue to confront. As a human services provider and mandated reporter, it is imperative to ask clients direct questions about their emotional well-being and comply with legal requirements. It is not enough to pose the questions; the language used and the relationship established with clients must be carefully managed. Therefore, comprehensive training is essential to prepare service providers to support clients in reducing the number of deaths by suicide and destigmatizing the conversation. The ultimate goal is to prevent suicides, even if it means engaging in difficult conversations, as visualized in figure 7.5.

Suicide and suicidal behavior stem from adverse conditions in which people live, work, learn, and play. These conditions, also known as social determinants of health, include but are not limited to economic hardship, poverty, racial discrimination, limited affordable housing, lack of educational opportunities, and obstacles to accessing physical and mental healthcare. Factors such as relationship problems or feelings of social isolation, easy access to lethal means, experiences of violence, adverse childhood experiences, bullying, and severe health conditions can increase the risk of suicide.

While suicide risk affects anyone, some groups are more susceptible to negative social situations and other factors that contribute to suicide, making them vulnerable to higher rates of suicide or suicide attempts. Some communities of those communities that have a disproportionate burden of suicide are veterans, rural communities, sexual and gender minorities, older adults, people of color, and tribal populations.

Preventing suicide and suicide attempts entails creating favorable social conditions and identifying and managing factors that contribute to suicide risk. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is mainly concerned with groups disproportionately impacted by suicide and uses a comprehensive public health approach to reduce suicide risk and promote resilience and well-being in communities, ultimately saving lives.

According to a 2021 report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), more than 48,000 individuals in the United States died by suicide, equivalent to one death every 11 minutes. Shockingly, 12.3 million adults have experienced severe thoughts of suicide, 3.5 million adults have made plans, and 1.7 million have attempted suicide. Notably, Native communities and males have the highest number of deaths by suicide. Firearms remain the leading cause of death by suicide, followed by suffocation.

Oregon legislators have acknowledged the importance of providing more resources to support mental health and suicide prevention in schools. Consequently, the introduction of SB 52, also known as Adi’s Act, “mandates that all school districts in Oregon must have a policy in place that addresses the issue of youth suicide and works towards destigmatizing mental health struggles.”

Oregon also has a law that allows students to take up to five excused absences within three months for either mental health or sick days. However, exceeding this limit requires a written excuse from a medical professional. The bill was signed into law by Oregon Gov. Kate Brown in June 2019 to combat the high suicide rates among teens, making it one of the first state laws to explicitly instruct all schools to treat mental and physical health equally.

In 2018, Utah passed a similar law, but Oregon’s legislation is a more decisive and assertive step toward prioritizing the well-being of students. The State of Oregon wanted to move supporting the well-being of students forward with Transformative Social Emotional Learning (TSEL), the teaching standards that will be required to be rolled out starting in July 2024 to all K-12 schools, charter schools, alternative schools, and other non-traditional educational settings (Oregon Department of Education, n.d.). TSEL focuses on equity-centered, trauma-informed social-emotional learning, starting with adult social-emotional learning and systems, not curriculum. This shows the field of human services is also moving to a holistic view of mental health support, as we should. As human services practitioners positions in schools such as SEL coaches, McKinney Vento Liaisons, attendance coaches, are all going to be required to be aware and trained in TSEL as this will be a standard of care and support that all staff, students and families will be using across the State of Oregon.

Nonsuicidal Self-Injury, or Self-Harm

Cutting, burning, scratching, punching, pinching, puncturing, unprotected sex, or picking at wounds to prevent healing: there are many methods of nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) or self-harm, despite “cutting” being the often-used euphemism. Seventy-eight percent of people who engage in this behavior use more than one method (Adler & Adler, 2011). NSSI is a complex behavior that can accompany a number of mental health disorders or stressors: depression, borderline personality disorder, eating disorders, bipolar disorders, PTSD, negative body image, sexual abuse or trauma, and more. People of any age and gender may engage in this behavior (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Plante, 2007).

It can be very difficult for some people to understand why someone would engage in NSSI behavior, especially because many people who do so do not appear outwardly to have mental disorders, and may even be safety-conscious or risk-averse in other areas of their life—wearing seat belts, abstaining from tobacco use, etc. NSSI can present at any age and in any gender; however, it has been socialized to be recognized more in teenage girls. We must be careful to not assume that they are the only people impacted, as self-injury or self-harm behavior can look so many different ways, as indicated in figure 7.6.

Many people who engage in nonsuicidal self-injury say that they do so to relieve what some may consider “negative emotions” like frustration, jealousy, loneliness, sorrow, or anger. The physical pain, in a sense, distracts them from their emotional pain. The neurotransmitter rush that may accompany self-injury helps to counteract the negative emotions (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Walsh, 2012; Plante, 2007). Others report that they feel numb to the world around them, or think they’ve forgotten what it’s like to feel anything. Nonsuicidal self-injury reminds them that they can indeed feel, and that they are alive.

Still others have intense negative feelings about themselves and hurt themselves because they feel they deserve it. These individuals (as well as those mentioned in the previous paragraph) may very well injure themselves in places that will not be seen by others due to being covered up by clothing. Some may be intentionally cause injuries in conspicuous, visible places that they know will get the attention of loved ones or authority figures who will then help the self-injurer receive the necessary treatment to address whatever is going on (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Plante, 2007; Walsh, 2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury is often seen in adolescents and young adults who are exceedingly perfectionistic (academically, regarding body image, etc.) and/or dealing with family dysfunction or divorce (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Walsh, 2012; Plante, 2007).

When self-injurious behavior is noticed, it is important to address it as quickly as possible. The longer one waits, the more difficult it can be to get treatment. Self-injury can become addictive, may be the only coping mechanism the individual uses for negative emotions, and may be bringing them a lot of attention—though not a healthy sort (Plante, 2007). Ignoring the behavior, or hoping it goes away, may inadvertently send a message that it is nothing to take seriously or that you are not concerned about the person who is self-injuring. Without intervention, the behavior can escalate as the self-injurer builds up a tolerance of sorts and begins to cut or otherwise hurt themselves more severely (McVey-Noble et al., 2006; Adler & Adler, 2011).

An important and common question is whether there is a link between nonsuicidal self-harm and suicidal behavior. There is definitely enough of a connection to cause concern. Most people who self-injure do not wish to die, and nonsuicidal self-injury should not automatically be taken as evidence of suicidality; however, research has placed the percentage of self-injuring individuals who also display some suicidal behavior at 50 to 90 percent, and 28 to 41 percent of those who self-injure have suicidal thoughts while self-injuring (McVey-Noble et al., 2006). People who engage in non-suicidal self-injury, regardless, are almost certainly suffering from some degree of pain and turmoil, whether they want to die or not. Successful treatment methods exist (Walsh, 2012). Cultural considerations are important.

Working with Womxn

It is important to have a shared understanding of how the word womxn will be defined in this text. Womxn is a term that is much more inclusive of many more people than only those assigned female at birth based on external genitalia. The concept began to be used in intersectional space in the 1970s to be inclusive of nonbinary people and transgender women. Not every nonbinary person connects with the experience or identity of being a woman; however, there are some that do, and this term is inclusive of such.

Womxn has also caused some pushback in other communities, as some feel it takes from other experiences, though it is not meant to. When one group is uplifted, it does not take from another; it brings up everyone. This comes up many times when considering the women’s movement. Many believe that “allowing” transgender women into such movements takes away rights that earlier feminists—specifically White feminists—had fought for. If we begin to exclude who counts, we become the oppressors pretty quickly.

Without womxn as clients, we would need a lot fewer providers, yet many of our approaches are focused on men. We have not devoted as much research to problems that specifically impact womxn, like perinatal mood disorders or an understanding of how specific disorders like major depression or substance use disorders manifest differently for womxn. To give you an example, a quick search of the EBSCO research database in 2021 revealed 8,730 articles with a mention of perinatal depression, formally known as postpartum depression, but a whopping 15,041 when the search is for erectile dysfunction. The Federal Drug Administration (FDA) did not even start testing on female bodies until 1993 which shows how little we actually know about how many of the drugs or other medical devices on the market truly impact over half of the world’s population. We are starting to pay more attention to these imbalances in treatment knowledge and the increase in funding needs and supports in treatment programs, providers and overall research.

Critics have also recognized problems in using treatment approaches that were designed by men from their own perspective of what would be helpful and using those same approaches to help womxn. For example, feminist practitioners and theorists have been critical of the traditional twelve-step approach of programs such as Alcoholics Anonymous as it relates to womxn.

The first step involves admitting powerlessness. Women who have stated in groups that they already felt powerless, and that this may be part of what led them to abuse alcohol, have been at times “shamed, threatened with abandonment, and called resistant” to the twelve steps (Matheson & McCollum, 2008, p. 1028). Submitting further to an admission of powerlessness may actually increase women’s insecurity and sense of oppression, putting further roadblocks in the way of their recovery. Those who already feel disempowered are not likely to find it helpful to start a program that insists on an admission of powerlessness (Matheson & McCollum, 2008). Powerlessness got them into their addiction in the first place, feminists might say. These women need to feel empowered and transformed instead of powerless.

From a macro perspective, we have to recognize that there may be a reason women seem to have higher rates of depression and other mood disorders, and it may not necessarily be physical or neurochemical in nature. “The mental health of women and their low social status are intricately intertwined…Any serious attempt to improve women’s mental health condition must deal with the ways in which their mental health is affected negatively by social customs and cultural considerations” (Wetzel, 1995, p. 177). When women are treated as if they are lesser than men—as they are in virtually every society today, to some degree—it should be no wonder that they suffer from various mental illnesses. They may find themselves relegated to lower-paying jobs and have a greater likelihood of ending up in poverty. The patriarchal system tells them they cannot succeed, puts limits on their abilities to improve their lives, and then calls the natural emotional and psychological results of systematic oppression a “mood disorder” or “mental illness.”

Men are less likely to feel they live in unsupportive, controlling environments and therefore are more likely to feel comfortable being assertive. Women in counseling may have to be assisted in learning assertive behavior to help them have better chances of achieving what they would like for themselves and their families (Wetzel, 1995).

Janice Wood Wetzel (1995) has several macro-level suggestions that she feels could make a bigger impact on the overall mental health of women. It requires more than simply continuing to treat individual women’s problems as they present in social work and counseling offices. They include:

- “Raising consciousness regarding gender roles and the importance and worth of every female.” (p. 181)

- “Addressing the fundamental right of every woman to live without fear and domination, whether in the home or society, and to be educated and treated with respect.” (p. 183)

- “Sharing home maintenance and child care with men on an equal basis; restructuring the family and society from a human rights perspective.” (p. 184)

- “Teaching fundamental rights regarding health needs, both emotional and physical, including the individual and mutual need for nurturance, freedom from exhaustion, and participation in decision making, within and outside the home.” (p. 185)

- “Teaching women that both personal development and action, as well as collective social development and action, are essential if their lives are to change for the better.” (p. 186)

- “Engaging in participative social action research, culminating in new policies and laws, as well as participative psychosocial programs for social change” (p. 187).

Addressing women’s individual mental health concerns, while still important, may be treating the symptom of a systemic problem. In order to make a more significant change in the overall mental health of women in the United States and abroad, efforts toward greater equality may be more productive. This is an issue that can be approached from micro, mezzo, and macro angles.

LGBTQIA2S+ Clients

Though there is greater acceptance than ever in America for LGBTQIA2S+ people, substantial prejudice still exists and is at times even socially sanctioned. Having to deal with oppression, disenfranchisement, and discrimination from society at large is difficult, but LGBTQIA2S+ clients also deal at times with similar behaviors from family and friends. Needless to say, this treatment from strangers and loved ones alike can bring about significant mental health concerns.

LGBTQIA2S+ people are impacted by depression at a higher rate than the general population, and counselors who behave in heterosexist or heterocentric ways can become barriers to LGBTQIA2S+ people seeking treatment (Bellenir, 2012). However, before moving on to anything else, it needs to be clear that LGBTQIA2S are not all the same; some are communities of sexual attraction, and others are gender or intersex. It is essential to understand that as much as we may see all those letters together, they are not all the same and to understand the complexity of this community is part of our own.

Before moving on to what most students want, a list of “dos and don’ts” for quick reference, we must be clear about our language. What does LGBTQAI2S+ even mean? Does it even make sense to have all those letters together? Should more be added? Am I missing something or anyone? The answer to all of these is yes and no.

Barrett & Logan (2002) offer the following tips for working with LGBTQIA2S+ clients in counseling.

- Be aware of your own internalized prejudice: Being raised in a heterocentric society, it is natural for most counselors to exhibit some heterocentrism, often without recognizing it.

- Be prepared to assist clients with coming out: Be supportive and appropriately aware of the potential pitfalls and difficulties with the process; respect their desire to come out at their own pace. This also means that we need to consider how intersectionality plays a role and that many people do not feel they need to, want to, or are safe to come out. The experience of being a lesbian Native woman is different from that of a gay White man.

- Be aware of the effects of prejudice: Recognize that clients have been dealing with negative treatment by society and may be living in a world different from the one you inhabit if you are heterosexual. They may not have experienced society as a supportive and helpful place, and therefore may anticipate different reactions from others than you would.

- Actively address and combat societal oppression: Think macro! If you want your LGBTQIA2S+ clients to have better mental health functioning, one way to help is to work on changing the environment to reduce those stressors of negative societal reactions and treatment toward your clients.

- Be comfortable and able to talk about sex and sexuality: Do not allow your client to feel like they need to approach the topic of sex indirectly. Be as willing to discuss their sex life and related concerns as you would with a heterosexual client.

- Recognize that intimate partner violence and substance use does occur in same–sex relationships: Make sure to have a list of LGBTQIA2S+ friendly resources at the ready for such situations, and react in the same supportive way you would to any other individual dealing with domestic violence.

- Use the terms clients use: If clients use terms like boyfriend/girlfriend, husband/husband, wife/wife, partner/partner, or anything else in their relationships, follow their lead. Don’t feel the need to guess—if you are unclear what to say, just ask what the client(s) would prefer.

- Avoid over-focusing on sexual orientation or gender identity: Like heterosexual, cisgender clients, LGBTQIA2S+ clients have problems that they do not perceive as related to their sexual orientation or gender identity. Do not feel the need to connect every issue back to those elements of identity.

The bullet points above are not the only list we must follow as every individual has their own experience of the world, and neurodivergence, intersectionality, and unique needs are considered when we think about the cultural considerations of any community. Only some people from the LGBTQIA2S+ have the same belief systems, political set of values, family structures, and religious beliefs. So, it is unclear to many why this community’s letters clustered together when they are sometimes not connected for some people in the community, and for others, they are interwoven. Some of the letters are much more well-known than others.

- Lesbian: Women who are attracted to other women.

- Gay: Men who are attracted to other men.

- Bisexuals: Someone who is attracted to more than one gender.

- Transgender is an umbrella term that is used to represent a person who identifies with a gender that differs from the gender assigned at birth.

- Q: Queer is a term that the community has reclaimed in the last few decades, as it was used as a slur in the past, and some in the community may not feel that this term should be used, but the term Queer is not used by many as a way of encompassing questions, exploring or in general falling outside of society norms.

- The letter I represent Intersex, an umbrella term that describes a wide range of natural body variations that do not neatly fit into conventional definitions of male or female. Intersex variations may include but are not limited to, variations in chromosome compositions, hormone concentrations, and external and internal characteristics.

- The A stands for Asexual; Asexual is defined as people who have little to no desire for sexual attraction but desire emotional and spiritual attraction and relationships.

- 2S The term “Two Spirit” may be unfamiliar, but it has a rich history in the pre-colonial United States. Two Spirit individuals, often abbreviated as 2S, were respected as spiritual leaders in early Native societies. They embodied traits of both men and women and sometimes identified as male, female, or Intersex. They held notable roles, such as storytellers, counselors, and healers. However, these traditions have been threatened by colonization and historical trauma. Despite this, Two Spirit people across North America are working to revive their traditional roles.

Self-care and Community Care

Many professions talk about the importance of self-care and perhaps even created plans to support what self-care will look like in their lives. But what is self-care exactly? Self-care is defined as needs for overall well-being. It helps manage stress, reduce ailments, and foster positive emotions for a healthier life. Self-care can be viewed in eight domains: environment, physical, social/relationships, emotional, spiritual, professional, financial, and community. Self-care has often been talked about as bubble baths, getting manicures, going to dinner with friends; everything seems to be connected to some kind of monetary value and is made a check list item to complete. This often makes self-care seem selfish because people are spending money on themselves on what sounds like frivolous categories or an assignment to be completed and move on. However, self-care can be looked at in nine different domains and is anything but frivolous:

- Environment: This includes your living structure, is your space free of clutter and organized, you have a space that you feel comfortable and safe (this is up to you to decide what safe feels and looks like), privacy is a key component of this space also. It is important to know that privilege and access to resources is something that can limit what this can look like for some communities and people.

- Physical: It ensures enough sleep, nutritious food (consider cultural and decolonization needs), drinking enough water, physical touch, sexual needs, getting daily natural sunlight, limits on screen time especially during the morning and before bedtime and movement for your body’s needs at least 15 minutes a day. Your needs will fluctuate based on the rhythm of your life and reminding oneself to have grace for the changes in life as trying to have a perfect balance is impossible. Consider each individual’s differing (dis)abilities and mobility needs.

- Social: Prioritizing relationships is essential, and tending to your social well-being involves nurturing your connections. This can be accomplished by spending quality time with individuals who motivate and uplift you, be it friends, family, or trusted confidants. It’s vital to distance yourself from negative social circles that do not contribute to your well-being. Social self-care may entail seeking new, meaningful friendships and connections. Joining like-minded groups, volunteering at special events, or exploring new activities are all effective ways to achieve this.

- Emotional: Emotional self-care helps us understand our emotions, navigate challenges, and build strong relationships. By tending to our emotional needs, we enhance compassion, kindness, and love for ourselves and others, contributing to our overall well-being. Acknowledging and discussing our feelings with trusted individuals or professionals is essential for managing our emotional well-being.

- Spiritual: The spiritual dimension of self-care is a deeply personal practice that allows you to align with the values and beliefs that give your life meaning. Even if you’re not religious, connecting with the spiritual dimension remains important. It can help you discover more meaning in life, cultivate a sense of belonging, and reduce feelings of isolation and loneliness. If you’re trying to escape negative social circles, social self-care may involve seeking new, meaningful friendships and connections through joining like-minded groups or volunteering at special events.

- Professional: Engaging in professional self-care is important for maintaining overall well-being and growth. This can encompass a variety of practices, such as effectively prioritizing tasks, establishing realistic and achievable goals, delegating responsibilities when appropriate, and taking regular breaks to stave off burnout. Furthermore, ongoing learning and skill development are vital in fostering professional growth and job satisfaction.

- Financial: If dealing with personal finances stresses you out, practicing self-care in this area is important. Cultivating a healthy relationship with money is crucial for mental well-being, as it can reduce stress and anxiety. Financial self-care can also lead to a more positive attitude towards money, making us more open to discussing it and less envious of others’ financial status.

- Community: It is about how our choices impact the community, not just the neighborhood we currently reside in but the future generations of people we interact with. Many cultures have interdependent beliefs in their way of life, community care, and environmental practices. They think of the lands they live on, the earth, and the people not as separate but as people in direct connection with each other, which significantly impacts future generations.

Community is the last domain mentioned above and directly related to the second kind of care that is interconnected to self-care. Community Care, is defined as the care that BIPOC and QTBIPOC communities emphasize the interconnectedness of individual and community well-being, fostering connections, recognizing systemic inequities, and creating new structures to address these issues. It aims to promote a more equitable future through mutual support, addressing social determinants of health and resource gaps. Community care seeks to create new structures and increase access to valuable resources through mutual support and aid provided by individuals and the broader community.

Remember that self-care and community care are not meant to prepare you to give all of yourself to others. These actions also do not genuinely care for anyone, including yourself. The idea that you cannot fill up anyone else’s cup if your cup is empty is something that, as a Human Services field, we must stop saying. Caring for your well-being is not about sacrificing all your energy and resources for others; you should not compromise your own needs as a human for the needs of others. If that self-care you give yourself benefits others, that is amazing, but the purpose of self-care is not to turn around and give it all to others. You are enough; you, as a human, have value.

Both self-care and community care are parts of mental wellness that human services providers and this field can do a much better job in promoting starting from classroom and learning spaces, educators doing it during mentoring sessions, internships encouraging this with their interns and it being part of active conversations in codes of ethics conversions.

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“The Label, Not the Person” is adapted from Introduction to Human Services 2e by Elizabeth B. Pearce, licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Figure 7.5. “Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration is in the public domain.

Figure 7.6. “self harm awareness Nov 30 black ribbon” by TraumaAndDissociation is licensed under CC BY ND 2.0.

Figure 7.7. “Graffiti at the Ambedkar University Delhi, students 2018” by Frederick Noronha is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

Figure 7.8. “Self-Care” by Soozie Bea is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

a professional field focused on helping people solve their problems.

shared meanings and shared experiences by members in a group, that are passed down over time with each generation

a biological descriptor involving chromosomes, primary, and secondary reproductive organs.

socially created and poorly defined categorization of people into groups on basis of real or perceived physical characteristics that has been used to oppress some groups

the socially constructed perceptions of what it means to be male, female or nonbinary in the way you present to society

an approach based on scientific evidence, client values, and clinical experience.

the state of lacking material and social resources needed to live a healthy life

traumas that occur in an individual’s life before they turn 18, which include neglect, abuse, and household difficulties

develop strategies that fend off problems

Agreed upon level of quality in selected areas.

provision of what each individual needs in order to receive and obtain equal opportunities.

results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or life threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being

maltreatment, violation, and exploitation where a perpetrator forces, coerces, or threatens a child into sexual contact for sexual gratification and/or financial benefit, including molestation, statutory rape, prostitution, pornography, exposure, incest, and other sexually exploitative activities

action taken to improve a situation or address a problem

an academic rank conferred by a college or university after completion of a specific course of study.

race, class, gender, sexuality, age, ability, and other aspects of identity are experienced simultaneously and the meanings of each identity overlaps with and influences the others leading to overlapping inequalities

a person’s emotional, romantic, erotic, physical, and spiritual attractions toward another in relation to their own sex or gender.Sexuality exists on a continuum or multiple continuums

any incident or pattern of behaviors (physical, psychological, sexual or verbal) used by one partner to maintain power and control over the relationship

action to preserve and improve one’s own physical and mental health.

moral principles.