9.3 Care and Healing for Aging Adults in Community

As human services and social work professionals, we need to analyze and learn from the historical and global approaches to caring for and supporting the aging adult population. By doing so, we can gain valuable insights and knowledge that can help us effectively address the varied needs of our elderly clients.

We can utilize several theories to understand the different stages of aging. For instance, Erik Erikson’s theory of Integrity vs. Despair as a late life stage and Gail Sheehy’s New Stages of Adult Development in her book New Passages: Mapping Your Life Across Time comprehensively understand the psychological and emotional changes that occur as people age. For a deeper dive into Sheehy’s work, watch the optional video, “Gail Sheehy offers a roadmap to the stages of adult life” [Streaming Video]. However, more is needed to truly understand our limited knowledge of aging with these theories alone.

It is essential to recognize that aging adults face unique challenges that require our attention. One of the most significant challenges is the increasing isolation from their families and communities that many seniors experience. This trend is particularly evident in the United States, where individualism is highly valued. In contrast, other countries have more collectivist social structures that prioritize the community’s well-being over the individual’s. As providers, we must consider the cultural and social factors that contribute to the isolation of our elderly clients and work toward developing strategies that can help them remain connected to their families and communities.

Multigenerational Homes around the World

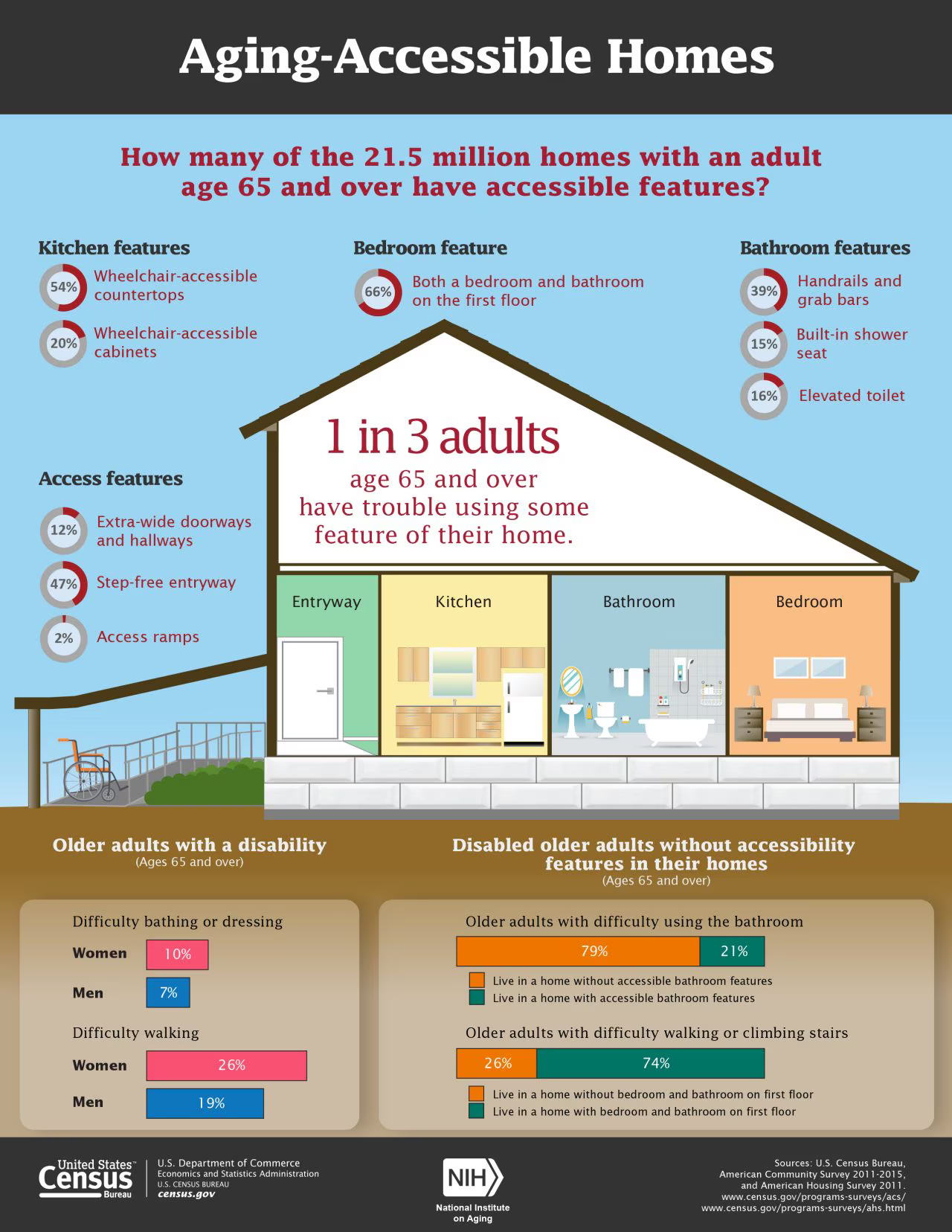

Caring for aging adults in multigenerational homes has been a longstanding tradition that reflects the importance of familial bonds and cultural heritage. In the United States, this practice has become increasingly prevalent as families take on the role of caregivers for their elderly loved ones. Unfortunately, this responsibility often comes with little support from society, government, and health care systems. Even the housing system is biased against multigenerational living, as depicted in figure 9.5. Conversely, in some countries, the social structure promotes multigenerational homes as the norm, encouraging children to live with their parents until they are married and have families, children, or their own homes. This means that some children could be living at home until the age of 35 or 40 as a standard instead of living on their own at a younger age of 18 or early 20s as many see here in the United States.

In many BIPOC families, grandparents, parents, partners, grandchildren, and cousins share the same living space, creating a unique and vibrant household. Grandparents often hold a central role in these families, serving as a cultural compass to guide essential decisions regarding stories, history, food, traditions, and significant life events. As a symbol of a community’s past and future, elders are revered and respected, and caring for them is considered a shared responsibility that benefits the whole family.

In the Latine community, the grandparents’ role is often particularly significant. They live with their families throughout their lives and play a vital role in decision-making, from purchasing property to naming grandchildren. Even in modern children’s movies, the importance of elders is highlighted in storytelling, weaving, cooking, music, and decision-making. Caring for elders is seen as both a privilege and a responsibility, with the eldest child traditionally taking on the overall care responsibility, which is then shared among all family members.

Research has shown that intergenerational relationships between aging adults and children promote self-esteem, friendships, and social-emotional skills. Studies in the United Kingdom, Australia, and Japan have demonstrated the positive effects of these relationships, which can also decrease isolation for the aging adult population and encourage the passage of cultural wealth. As providers, we should explore ways to structure our systems to support this system of intergenerational care, recognizing the benefits it provides to older adults and the larger community.

To learn more about intergenerational relationships, optionally read one of these articles:

- Combining daycare for children and elderly people benefits all generations [Website]

- Intergenerational Programs to Promote Active Aging: The Experiences and Perspectives of Older Adults [Website]

- An evaluative study of the benefits of participating in intergenerational playgroups in aged care for older people [Website]

Examples of Multigenerational Care in the United States

Upon completing my bachelor’s degree in psychology, I was offered my first position as a home visitor for Head Start at the Oregon Child Development Coalition (OCDC). OCDC was created in 1971 to provide migrant farm working families with secure access to childcare following a tragic incident involving a young child. While the agency’s primary mission remains the same, they have extended their support to other community needs. Their educational program is designed to foster volunteer and parent/family involvement, focusing on older adults’ essential role in caring for children, much like they would in their traditional homes. To learn more about this organization, optionally watch “We Are OCDC” [Streaming Video].

As I visited families’ homes to discuss parenting and family care, I realized that multigenerational families were the norm. Home visits often included not just the parent and child but siblings, aunties, grandparents, and even neighbors. Adapting to the courses and curriculum was challenging until I changed my outlook and viewed the family as the client for some visits. This made assessments more transparent, manageable, colorful, and comprehensive.

In my home visiting plans, I integrated older adults’ involvement in parenting as their traditions offered guidance on supporting the next generation. Therefore, many conversations I had were happening with them alongside. Some critical aspects of home visiting involve decreasing childhood injuries, educating parents on co-sleeping, healthy eating habits during pregnancy at each trimester, and developmental milestones to look for in their child as they grow, plus when to seek support if they are not meeting these milestones.

I began to understand that if I wanted to gain the trust of the parents and other family members, I needed to have the grandparents understand the purpose of my visits. Grandparents become, at times, co-facilitators of some visits, making them central to the education of their grandchildren.

Licenses and Attributions

“Care and Healing for Aging Adults in Community” by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

“Examples of Multigenerational Care in the United States” by Martha Ochoa-Leyva is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.5. Aging-Accessible Homes by U.S. Census Bureau is in the public domain.

Rice University, Introduction to Sociology 2e. OER Commons, http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, Introduction to Sociology 2e | OER Commons

Spielman, R. (n.d.) Psychology: Unit 10, Lesson 4-Stages of Development. Rice University, OpenStax College, https://www.oercommons.org/courseware/8430, CC BY 4.0.