9.4 Challenges Facing Older Adults and Their Families

As an individual, take a moment to think about what you do to keep yourself as youthful as possible. While not everyone will come up with an answer, a good majority of people will come up with at least one thing they do to combat aging, both physical and mental. Whether it is working out to stay fit and strong, doing mental aerobics with puzzles to keep your wits sharp, or using facial creams and/or plastic surgery to prevent or get rid of wrinkles and other visible signs of aging, many people are trying to stay young for as long as they can. While the impetus for these measures might be to prolong life as long as possible, some strategies Americans use are really more to prolong youth.

As a society, we put so much emphasis on staying young, especially physically. One article reported a study presented at the annual conference for the American Public Health Association that indicated we spend more money on medication targeting what used to be thought of as natural effects of aging, such as “mental alertness, sexual dysfunction, menopause, aging skin and hair loss,” (para. 2) than we do on prescriptions designed to counteract chronic illnesses (Drevitch, 2012). Add this to the amount of money spent on over-the-counter anti-aging creams, makeup designed to cover wrinkles, and hair dye, and we have a better understanding of how society tries to prevent or avoid the aging process.

Baby boomers, those born between 1946 and 1964, are redefining how Americans look at age. Old age is no longer seen as a time of fragility and senility, but rather a time of wisdom, being active, and purposeful living (Wilson, 2014). In fact, a study conducted by the Pew Research Center found that a majority of American adults feel their life will be as satisfying or better ten years from now, including a two-thirds majority of those who are considered old-aged (Pew Research, 2013).

Ageism

Yet ageism, which involves discriminating against someone based on their age, is still very prevalent in the United States. We may be comfortable with our own aging, but we generally do not want to acknowledge it unless we must. Then when we do acknowledge it, it is with the belief that we will be different—that when we grow old, we will not end up like those who came before us. We will make sure we take care of ourselves, unlike those we see around us. We may not internalize the negative beliefs about getting older as much as we used to, but that does not mean as a society we are completely sold on the usefulness of the aging population.

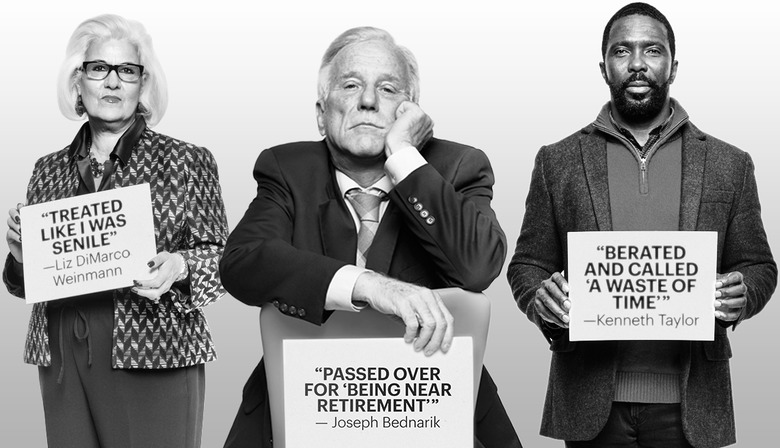

Ageism can be easily seen in hiring practices, as Americans closer to retirement age were displaced from their jobs due to the Great Recession, between December 2007 and June 2009, and as a result had to try to find new employment. A large number of aging Americans were forced into early retirement because of stereotypes. Stereotypes that we have about old age are translated into the workplace: older workers are considered less flexible in mindset, work style, and techniques, as well as being less efficient and reliable workers due to physical ability and health (Chou, 2012). These beliefs by employers can result in unfair hiring and firing practices, extended periods of unemployment, again forced by early retirement both directly by some companies however not explicitly for their age and by an inability to secure a new job.

Although stereotypes about aging might be based on a safety concern, generalizing the behaviors and abilities of a minority percentage of the older population to everyone in this group can cause us to view the older generation as a liability. An example, think of driver’s license requirements. Drivers who are 65 years old and over have a lower number of crashes and car insurance claims when compared to those under 65—especially the youngest drivers. Yet more than half of all states have specific license renewal requirements for older drivers that may include shorter renewal periods, vision tests, and road exams (IIHS & HLDI, 2015). Essentially, these regulations create an environment in which the aging population is seen as dangerous behind the wheel, when the facts tell a much different story.

American society demonstrates its bias toward youth in more than just its policies and practices. We also perpetuate stereotypes in consumerism and advertising. Products and services related to enjoying life, being active, and any kind of technology are typically marketed to younger audiences, while the products and services for taking care of one’s health, dealing with chronic illnesses, and preparing to live out one’s final years usually target older adults.

These practices perpetuate stereotypes and are based on both atypical experiences and an outdated understanding of old age. Defining older adults as physically weak and cognitively inept is incorrect. While some older adults may present this way, it is more the exception than it is the rule. Still, we are a long way from eliminating prejudice and discrimination.

Older adults are not universally valued. One study found that while college students did not blatantly discriminate against older people, they did not place importance on spending time with or learning from this group (Yilmaz et al., 2012). It is not only college students who feel this way. Many people in society behave as if aging adults are outlasting their usefulness to society.

It may seem easy to brush off societal messages (“I don’t pay any attention to ads”; “I laugh at the cards but don’t believe them”), there is a growing body of evidence that suggests that these messages are much more insidious than previously thought. Stereotype embodiment theory (SET) posits that the more a person is exposed to ageist messages, the more likely they are to believe—and demonstrate—these messages (Bengtson & Settersten, 2016). Exposure to negative aging stereotypes is associated with a variety of negative outcomes, including physical, cognitive, and emotional outcomes.

Numerous studies (Sargent-Cox, et al., 2015; van Wijndgaarten, et al., 2019; Choi, et al., 2019) have supported the theory that the more a person is exposed to negative aging messages, the more likely they are to believe these messages. The more they believe these messages, the more likely it is that they suffer from numerous issues, such as:

- Impaired balance

- Cardiovascular disease

- Memory problems

- Loneliness

Combating negative stereotypes is not just a matter of policy; it is a matter of public health.

We must also consider how oppressive systems have contributed to ageism.

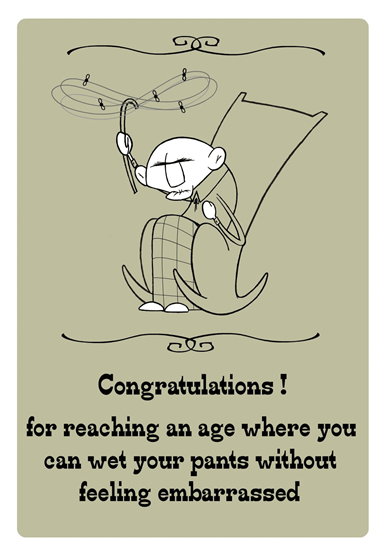

An Example: Ageism in Greeting Cards

It is easy to see with just a walk down the greeting card aisle how ingrained ageism is in American culture. This phenomenon is not only limited to the United States; however, many of these examples used are centered here. As human services providers, we understand that issues like these are not merely local, but global.

Birthdays are seen as a day to celebrate until about the age of 30, which is when the “over the hill” messages begin. Most of the cards aimed at adults have a theme of either cognitive or physical impairment, or a sense of impending death. These images and “jokes” are so prevalent that many people automatically laugh without considering the underlying message. Several organizations have begun campaigns to fight these ageist messages.

This campaign might make some people say, “We can’t joke about anything anymore.” But consider what this language perpetuates and how much harm it continues to cause, not just for those receiving the cards but those buying the cards. Why must we be a certain age or have a specific mental or body capacity to be considered worthy in society?

Mental Health Issues in Later Life

There are two distinct areas of mental health concerns in later life. One has to do with improved treatment for serious and persistent mental illness, while the other is related to the management of mental health along with other chronic diseases.

With improved medications and management of diseases like schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, people with these issues are able to live longer than previous generations. However, this also means that there is not a lot of research on managing these diseases in older adults. Questions such as appropriate dosage and interactions with other common medications taken by older adults are still being figured out.

Another issue is how to manage chronic mental illness along with other chronic diseases. For example, someone may have lived in a group home for their adult life, but they now also need to use a wheelchair. Are facilities that focus on mental health prepared to care for an aging population, or will the clients need to move as their care needs increase? Do our current long-term care facilities have the ability to handle mental health issues along with physical challenges? These are questions that are being posed right now.

The other focus of mental health in later life is people who develop mental illnesses later in life. This includes dementia, but depression and substance use are also major issues for older adults. Older adults are often facing multiple losses—deaths of friends and family, retirement, or changes in physical ability—that can be difficult to accommodate. Unfortunately, many medical professionals still have difficulty recognizing mental health issues in older patients. Even medical professionals sometimes say things like, “If I was in their shoes, I’d be depressed too,” and “They don’t have to work. Why worry about how much they drink?” It is important for family members and professionals to understand that depression and substance use are not a normal part of the aging process and can be successfully treated if recognized.

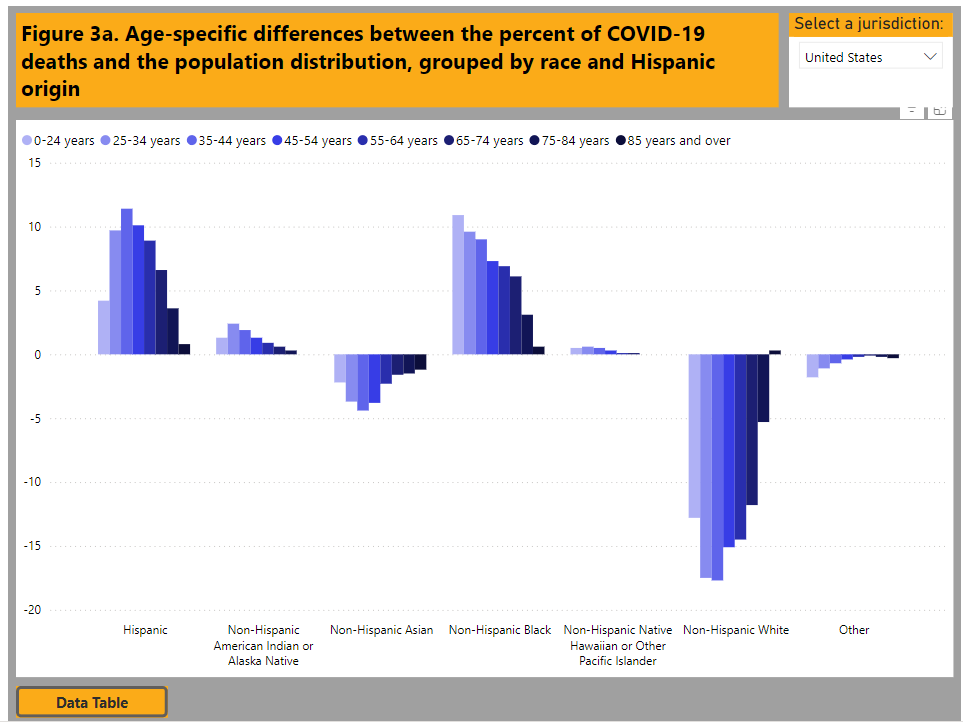

Another more recent crisis is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults. The statistics in figure 9.8 show us that while older adults were not more vulnerable to getting COVID-19, they were much more vulnerable to having serious complications, including death.

Many congregate living facilities (such as nursing homes and retirement communities) had outbreaks that devastated their communities. Almost all of the congregate living facilities in the United States closed their doors to visitors for a year or more. Older adults, like the person in figure 9.9, were isolated from friends and family members, only staying in contact by phone, email, or video chat. This includes multiple instances of family members having to say goodbye to dying loved ones over Zoom or FaceTime.

The Kaiser Family Foundation (Koma et al., 2020) reported that anxiety and depression increased in older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anxiety and depression were worse when older adults had complicating factors, such as other chronic illness or lack of resources. Depression and anxiety were lower when older adults had a feeling that they mattered rather than feeling expendable.

However, other studies that compared results between older and younger adults showed that while rates of anxiety and depression did increase in older adults, they were actually higher in younger adults over the COVID-19 pandemic (Varma et al., 2021). Some (providers in the field) speculate that older adults who had lived through other major events displayed more resiliency to the pandemic than younger adults with less experience (Pearman et al., 2021; Waugh et al., 2022). It is important that we recognize and support these strengths, especially in times of crisis, such as a pandemic. And again, we must recognize the diversity of experiences and reactions to the pandemic among older adults.

One study looked at the prevalence of “compassionate ageism” during the COVID-19 pandemic. Compassionate ageism involves regarding all older adults as needing and deserving of assistance without regard to the actual needs or desires of the older adult themselves. One example of this is referred to as “caremongering,” the assumption that all older adults are frail and in need of care.

This type of language regarding older adults is featured in many of the laws, measures, and procedures developed during the pandemic. While the intent of these interventions is well-meaning, they neglect to acknowledge the diversity of abilities and experiences for older adults. For example, at the same time that it was thought best to protect older adults with isolation, retired doctors, nurses, and other medical professionals were being asked to return to the field to help out overburdened hospitals. There was no acknowledgement that these professionals were also older adults.

Loneliness as a Mental Health Issue

Loneliness is the discrepancy between the social contact a person has and the contacts a person wants (Brehm et al., 2002). It can result from social or emotional isolation. Women tend to experience loneliness due to social isolation, men from emotional isolation. Loneliness can be accompanied by impatience, desperation, depression, and a lack of self-worth.

Being alone does not always result in loneliness. For some, being alone means solitude. Solitude involves gaining self-awareness, taking care of the self, being comfortable alone, and pursuing one’s interests (Brehm et al., 2002). In contrast, loneliness is perceived social isolation.

For those in late adulthood, loneliness can be especially detrimental. Novotney (2019) reviewed the research on loneliness and social isolation and found that loneliness was linked to a 40 percent increase in a risk for dementia and a 30 percent increase in the risk of stroke or coronary heart disease. This was hypothesized to be due to a rise in stress hormones, depression, and anxiety, as well as the individual lacking encouragement from others to engage in healthy behaviors. In contrast, older adults who take part in social clubs and church groups have a lower risk of death. Opportunities to reside in mixed age housing and continuing to feel like productive members of society have also been found to decrease feelings of social isolation and loneliness.

Licenses and Attributions

“Loneliness as a Mental Health Issue” by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Revised by Martha Ochoa-Leyva.

Social Work & Social Welfare: Modern Practice in a Diverse World | OER Commons

Lally, N. and Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan Development: A psychological Perspective-Second edition. Chapter 9-Late Adulthood. Licensed under CC BY NC SA.

Figure 9.6. Workplace Age Discrimination Still Flourishes in America © AARP. Image included under fair use.

Figure 9.7. Images from Funny Birthday Cards and “Dying Reward – Birthday Card” © Greetings Island. Image included under fair use.

Figure 9.8. Demographic Trends of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the U.S. reported to CDC is in the public domain.

Figure 9.9. COVID-19: residents of a retirement home on their first official group outing since Mid March lock-down by Gilbert Mercier is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 9.10. Photo by Yvonne M. Smith LCSW is licensed under CC BY 4.0.