3 Ethics and Values in the Human Services

Elizabeth B. Pearce

Ethics and Professionalism

As you consider entering the profession of human services, it is important to think about the role you will play as well as the responsibilities that come with that role. One of the joys and challenges of working with human beings is that unique interactions occur every day. Whether a director, a supervisor, a receptionist, an assistant or a case manager, you will encounter situations that you have not seen before. There is not a set of directions to follow when you work with individuals. When putting together a piece of furniture or preparing a tray of enchiladas you might follow instructions or recipes. You might even deviate a little bit or add your own flair to the project. Working with individuals and families, however, requires a stronger internal set of values and principles. That foundation is one that you build inside yourself using the tools of education, experience, and understanding about ethics.

Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals: https://www.nationalhumanservices.org/ethical-standards-for-hs-professionals

There is a code of ethics for the human services profession that will help you build that foundation. In fact you will be required to use that code as soon as you start working in this profession, including during your practicum and internship experiences. All professions have a code of ethics and those codes have many similarities in terms of how they relate to being responsible toward clients, colleagues, and society. Psychologists, attorneys, medical professionals, and social workers all embed these obligations and duties within their ethical codes. In this chapter we will focus on the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals; in the following chapter the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics is analyzed.

Whatever the profession, the code of ethics is embedded within the cultural ethos of the world and here, the cultural norms of the United States. As we examine ethics, we must also look at values and culture. It is important to note that different countries and cultures have differing values. and that there are many sub-cultures within the United States that conflict, complement and/or mirror the overriding norms of the country.

It is critical to pay attention to the cultures and values of the families that you work with, as well as being mindful of your own ethics and values. Looking at all of these elements together is complicated and that is why it is being highlighted right as you start learning about this profession. It takes time, experience, education and reflection to develop your foundation. This chapter will support that building process.

Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals

The field of human services was developed in response to human needs and human problems. It is a profession dedicated to helping diverse individuals solve the challenges that they face while valuing each person’s community, culture and self-determination. While doing so, the professional must act with integrity and compassion with social justice in mind. The set of ethical standards, adopted by the National Organization for Human Services in 2015, begins with a preamble that outlines the importance of each professional’s behavior and then goes on to describe 44 separate standards in the seven subject areas: clients, public and society, colleagues, employers, the profession, self and students. Following is a brief description of each section.

Preamble

The preamble contains four introductory paragraphs. The first two paragraphs focus on characteristics of the profession such as helping others and paying attention to the context of individuals and families. It emphasizes the role of education and professional growth.

A key part of the preamble is the acknowledgment of the conflict that may exist between the code and other policies and expectations such as employer policies, credentialing boards, laws and personal beliefs. Each entity has some shared but some differing priorities and this can lead to inconsistencies in what is best in any given situation. We will look at ethical dilemmas later on to help us understand this section of the preamble better.

The last part of the preamble reminds us that professionals as well as students and educators are bound by these standards.

Responsibility to Clients

Clients are the first and most obvious group to highlight. The very first standard describes the responsibility of recognizing and building on individual and community strengths. The prominence of this statement is key to the profession. There are nine total standards which include:

- Be strengths-based

- Obtain informed consent

- Privacy and confidentiality

- Protect from danger or harm

- Avoid of dual or multiple relationships

- Prohibit of sexual or romantic relationships

- Ensure that personal values or biases are not imposed

- Protect of client records

- Utilize technology in legal and confidential ways

Responsibility to the Public and Society

Human services professionals are not focused on a singular client, or discrete clients and families. There is a responsibility in this profession to visualize all of society, to pay attention to social problems and to how laws and policies affect communities. This profession has a social justice mission as these nine standards remind us:

- Provide services without discrimination or preference related to social characteristics

- Be knowledgeable and respectful of diverse cultures and communities

- Be aware of laws and advocate for needed change

- Stay informed about current social problems

- Be aware of social and political issues that differentially affect people

- Provide ways to identify client needs and assets and advocate for needs

- Advocate for social justice and to eliminate oppression

- Accurately represent their credentials to the public

- Describe treatment programs accurately.

Responsibility to Colleagues

- Coordinate, collaborate but do not duplicate services

- Deal with conflict by approaching the person directly; follow up with supervisor if needed

- Respond to unethical behavior of colleagues

- Keep consultations between colleagues private

Responsibility to Employers

- Stick with commitments made to employers

- Create and maintain high quality services

- In conflicts between responsibility to employer and responsibility to clients seek resolution with all involved.

Responsibility to the Profession

- Gain education and experience to work effectively with culturally diverse individuals based on age, ethnicity, culture, race, ability, gender, language preference, religion, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, nationality, or other historically oppressive groups.

- Know your own limits; serve others within those limits

- Seek help when you need it

- Promote cooperation amongst related disciplines

- Promote continuing development of the profession itself

- Continue to learn and practice new techniques; inform clients appropriately

- Conduct research ethically

- Be thoughtful about self-disclosure including on social media.

Responsibility to Self

- Develop awareness of your own culture, beliefs, biases, and values.

- Develop and maintain own health

- Commit to lifelong learning.

Responsibility to Students

This is the only section of the code that calls out a particular subset of human services professionals: the educators. The final seven standards emphasize the special duty that educators have to students who are in a relationship where power and status are unequal. Educators model the standards at the same time that they are teaching across the breadth of the profession. In particular the structure , quality, and adherence to the code of the class setting, including field experiences, are the responsibility of the educator.

- Develop and implement culturally sensitive knowledge, awareness and teaching methodologies

- Commit to the principles of access and inclusion

- Demonstrate high standards of scholarship

- Recognize the contributions of students to work of educators

- Monitor field experience sites; ensure quality and safety

- Establish guidelines for self-disclosure and opting out

- Awareness of power and status differential

- Ensure students are aware of ethical standards.

Embedded in Personal Beliefs and Society

Let’s dig a little deeper into some of the ethical standards and how they might lead to questions and dilemmas for practitioners. We will focus on the ways that individual standards may support or conflict with one another. In addition, we contrast and compare common standards with national culture, policies and practices. We also look at ways to examine your own values more deeply and how those connect to the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals. It is worthwhile to view the ethical standards in these multiple contexts. Using and interpreting the ethical standards are a career-long process.

Privacy, Confidentiality and Safety

Standards three and four appear in the second section of the Ethical Standards, for Human Services Professionals, Responsibility to Clients.

STANDARD 3 Human service professionals protect the client’s right to privacy and confidentiality except when such confidentiality would cause serious harm to the client or others, when agency guidelines state otherwise, or under other stated conditions (e.g., local, state, or federal laws). Human service professionals inform clients of the limits of confidentiality prior to the onset of the helping relationship.

STANDARD 4 If it is suspected that danger or harm may occur to the client or to others as a result of a client’s behavior, the human service professional acts in an appropriate and professional manner to protect the safety of those individuals. This may involve, but is not limited to, seeking consultation, supervision, and/or breaking the confidentiality of the relationship.

These two standards helpfully highlight the conflict between them in the last sentence of Standard four, which states that it might include “breaking the confidentiality of the relationship.” Similar conflicting ethical standards appear in most codes for helping professions. Facing the dilemma of whether to break confidentiality in order to preserve someone’s safety is one that many human services professionals will confront during their careers. In those circumstances, the worker should take into consideration:

- The applicable laws and regulations of the region (e.g. when and to whom are reports made)

- The workplace policies

- The worker’s role (e.g. counselor, manager, student, receptionist)

- The Ethical Standards

- Any other resources and expectations

Notice that the professional’s own personal beliefs and values are not on this list. Nor are local or religious beliefs and values considered relevant to putting someone in danger. This relates to Standard thirty-four and the self-awareness that each professional is bound to keep of their own cultural backgrounds, values, and biases. What dilemmas might this pose for the professional?

Social Justice

Standards fourteen and sixteen appear in the third section of the Ethical Standards, for Human Services Professionals, Responsibility to the Public and Society.

STANDARD 14 Human service professionals are aware of social and political issues that differentially affect clients from diverse backgrounds.

STANDARD 16 Human service professionals advocate for social justice and seek to eliminate oppression. They raise awareness of underserved population in their communities and with the legislative system.

Let’s look at a social issue (aka social problem) that is currently affecting the United States, but disproportionately affecting people who are in ethnic groups that have been traditionally underrepresented. A social problem is typically defined as one that affects many people, affects the health and well-being of society, includes multiple causes and effects, and needs a systemic solution. Social problems are discussed in depth in the What is a Social Problem? chapter.

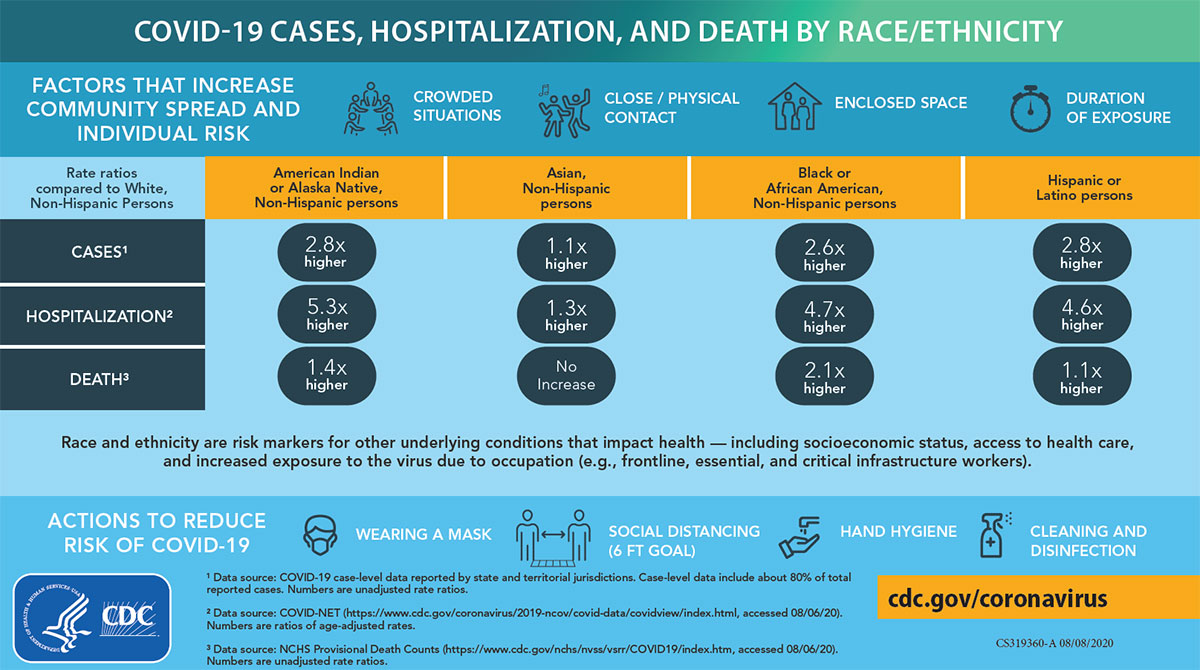

The COVID-19 pandemic is acknowledged to fit this definition. As a correlation, the disproportionate COVID-19 illness and death rate of people in ethnic minority groups could also be described as a social problem. In the United States (with data reported from 14 states) 33% of COVID-19 hospitalizations are among African Americans, although they make up 18% of the population in those states. In New York City, death rates were higher for Black (92 per 100,00) and Latinx (74 per 100,00) people than for White (45 per 100,000) or Asian (34 per 100,000) people. So Black and Latinx people who get COVID-19 are about twice as likely to die as are White and Asian people. Native American and Alaskan Native rates of death and sickness are also disproportionately greater. All of these trends are continuing to worsen. For the most up to date national and state data, click here.

While we have the data to know that this is a social problem, how does this related to the ethical standards? The next questions to ask are related. What contributes to underrepresented groups being more likely to get sick and also more likely to die if they are hospitalized for the illness?

The answers are complex, but here are some conclusions drawn from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other data. People from underrepresented groups are more likely to:

- Live in densely populated areas and housing with fewer services such as medical clinics

- Use public transportation more

- Work in jobs that are essential and/or require exposure to the public such as transportation workers, store clerks, and factories supplying food or other essential products

- Work in jobs that have few or no benefits such as sick leave or health insurance, meaning that they may be more likely to go work even if they or family members are sick.

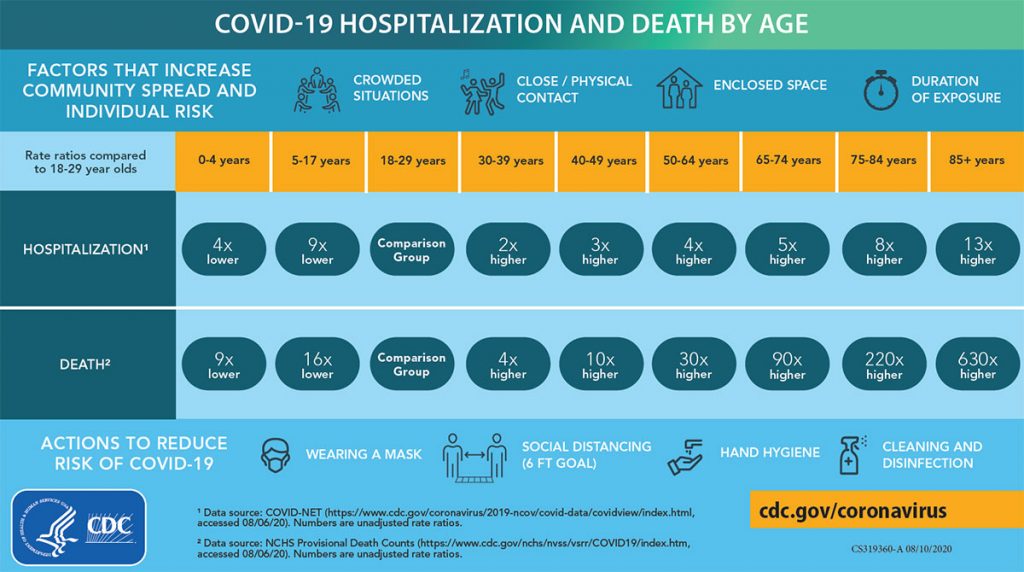

Although we have not discussed COVID-19 and age here, this chart is provided for contextual reasons.

Although we have not discussed COVID-19 and age here, this chart is provided for contextual reasons. Figures two and three: The CDC collects data related to disease, race, age, and ethnicity.

Figures two and three: The CDC collects data related to disease, race, age, and ethnicity.

Access to health care services and health care insurance is inequitable in the United States. In particular, states that have not expanded Medicaid funding as allowed under the Affordable Care Act have higher populations of ethnically underserved groups.

Whether this information is brand new to you, or you are familiar with this data, it seems obvious that there are multiple social problems to be unraveled and examined. Poverty and low socioeconomic status intersect with the racial and ethnic inequities examined here. All of us have been affected by the pandemic. Some of us have personal experiences with illness and death. related to the pandemic.

The question is, how does the human services professional adhere to ethical standards fourteen and sixteen? Standard fourteen talks about awareness. Just by reading this section of the text, your awareness has increased. What other steps could you take next to increase awareness? Standard sixteen moves to another level, requiring the human services professional to advocate for justice. Advocacy takes many forms. Here are a few ideas:

- Educate yourself about information literacy. What are reliable sources of information? Read and view those.

- Talk with people close to you. Share accurate information.

- Listen closely to people from underrepresented groups. Believe their experience. Stand by them.

- Write a letter or a postcard to your political representative.

- VOTE.

- Take part in the Census and the American Community Survey.

- Help amplify the voices of people of color (POC). Feature them on your social media.

In the field of human services there is an ethical responsibility to work toward a better society. The role a person plays in the workplace will define specific responsibilities and time, allotment but each professional will also have a commitment to the ethical standards and to working toward social justice.

Immersed in Values

Standard thirty-four appears in the seventh section of the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals, Responsibility to Self.

Our personal values and beliefs come from multiple influences: our families, geography, the time we live in and one or more cultures that may include religion. They also come from the broadly held values, policies, and culture of the United States, and we will focus on that here for a moment.

“There are these two young fish swimming along and they happen to meet an older fish swimming the other way, who nods at them and says “Morning, boys. How’s the water?” And the two young fish swim on for a bit, and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and goes “What the hell is water?” –David Foster Wallace

When we are immersed in something, we may not know exactly what it is. In the example above, the fish may not know to contrast water with other environments like the earth, or air. Living in the United States we are grounded in ideas such as “freedom”, “equality” and “patriotism.” But what do those words mean to you? And what do they mean in the context of the United States?

For example, The Declaration of Independence is commonly quoted to demonstrate that the United States is founded on equality,

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

But as we know, this declaration did not apply to all men in the United States, but only to men who were White, and in some cases was limited to land-owners (early in the history of the United States individual states regulated the right to vote, so there was variability about which White men had access to equality, including voting). Not to mention women, at a time when the White culture defined sex and gender in a binary system.

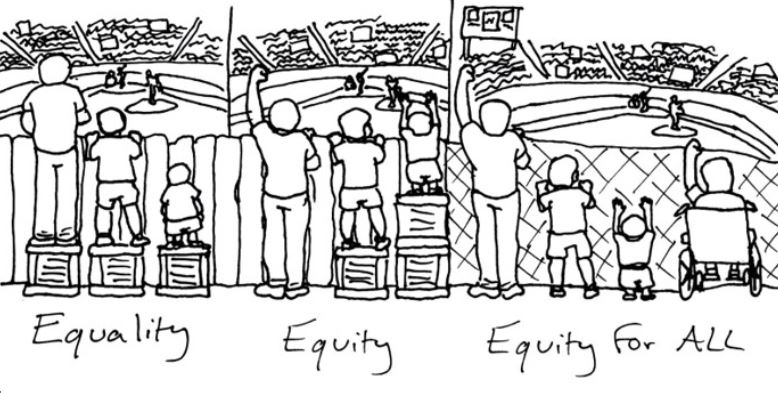

Here is another concept of equality that also incorporates the idea of equity. As you view the image, which definition do you find yourself the most aligned with?

In this drawing, “equality” is represented by each person having the same size box; “equity” shows each person having a box or boxes that help that person see over the fence; and in “equity for all” the solid fence is removed and everyone can see the game.

One lesson is that each professional needs to spend time thinking deeply about what their own values are, and how they define those values. Examine the source of those values. If they come from “the water” that you are immersed in, it may be time to poke your head out, reexamine and redefine your perspectives and values.

Standard thirty-four is about awareness: deep knowledge about yourself and about how your culture, beliefs, biases and values potentially interact with those of your clients and of society. This level of understanding does not come quickly or easily. While some of a person’s core beliefs and behaviors may be stable over time, most people grow, change, and deepen in their thinking and beliefs. Age, experience, education and action all contribute to greater self-awareness. Action can come in the form of reflective thinking and writing, interaction with other thinkers and practitioners, and via thoughtful listening and discussion. As a student in the field of human services, you are engaged in this process simply by reading, reflecting and discussing the ethical standards. You are not expected to have all of the answers, but you are expected to be engaged in the process.

Key Points

In this chapter the focus is on the Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals, with a reminder that most helping professions have similar standards. In the next chapter, the National Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics will be analyzed as a comparison and to look more closely at ethical dilemmas.

An ethical code must be considered within the context of multiple systems. The most complicated are the overlapping cultures that affect us: the cultural context of the individuals and families that are served, the professional’s own culture, and the ways that societal values and policies affect everyone. These are not to be given equal weight, but they are all factors in the work and ethical life of the helping professional. In addition, the practitioner must also consider laws, community practices, and workplace expectations.

The purpose of presenting these interwoven concepts now is to give human services students an introduction to the ideas. There will be opportunities throughout time, education, and experience to consider these ideas and develop your understanding and practice of ethics. Reflect, discuss, act, and reflect again. Having an ethical code is a tool that will serves practitioners, the people serve, and society.

References

As pandemic deaths add up, racial disparities persist—And in some cases worsen. (n.d.). NPR.Org. Retrieved September 25, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2020/09/23/914427907/as-pandemic-deaths-add-up-racial-disparities-persist-and-in-some-cases-worsen

CDC. (2020, April 30). Communities, schools, workplaces, & events. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

Declaration of independence: A transcription. (2015, November 1). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript

Kirby, T. (2020). Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, 8(6), 547–548. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30228-9

National Organization for Human Services. (2015). Ethical Standards for Human Services Professionals. Retrieved from https://www.nationalhumanservices.org/ethical-standards-for-hs-professionals

Licenses and Attributions

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure one. “Personas mirando en la noche” from https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1454151 by Susan Cipriano in the public domain

Figures two and three. “COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by race and ethnicity” and “COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths by age” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are in the public domain

Figure four. “David Foster Wallace” from https://images.app.goo.gl/uP58FceupdfJK8UQ7 by Steve Rhodes is licensed by CC BY NC SA 2.0

Figure five. “Equality, Equity, Equity for All” by Katie Niemeyer. License: CC BY 4.0. Based on ideas originally illustrated by Angus Maguire and Craig Froehle.

Figure six. “19_03_2010-Open Water Diver-TauchSport-Steininger” by TauchSport_Steininger is licensed under CC BY 2.0